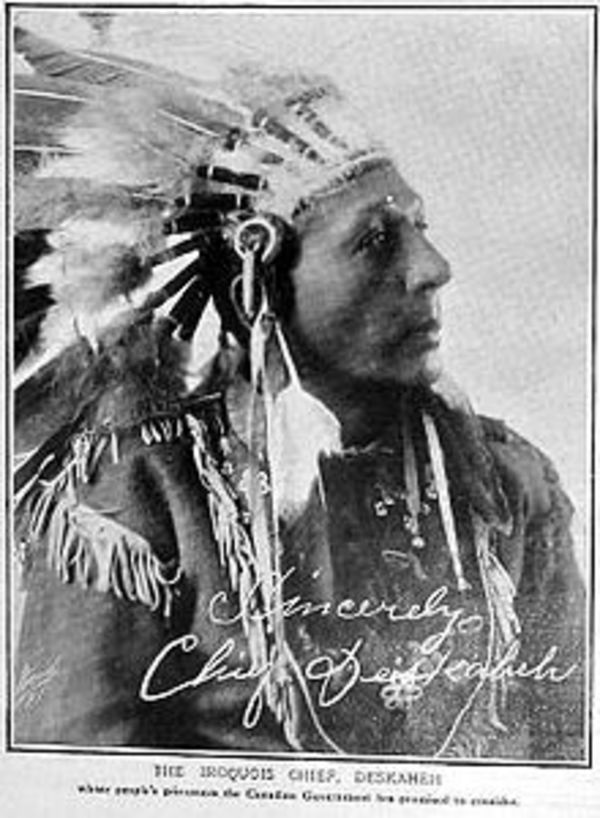

Source: Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

DESKAHEH (Levi General), farmer, Cayuga chief, and activist; b. 15 March 1873 in Tuscarora Township, Ont., son of William General and Lydia Burnham; m. before 1898 Mary Bergen, and they had four daughters and five sons; d. 27 June 1925 on the Tuscarora Reservation, N.Y.

A descendant of Iroquois with some Scottish-Irish ancestry, Levi General was born on the Six Nations Reserve on the Grand River. His Oneida mother and Cayuga father, who ran their own farm but worked out during harvest season, had a family of eight, Levi being one of the older children. At primary school he had Christian teachers, but he remained an adherent of the traditional Longhouse religion.

The Six Nations community contained two distinct religious worlds: that of the Mohawk, Oneida, Tuscarora, and Iroquois allies such as the Delaware, who accepted Protestant Christianity, and that of the Seneca and Onondaga, who adhered to the teachings of Skanyátaí.yo? (Handsome Lake), who had reformed the Iroquois religion in the early 19th century. The Cayuga included both Christian and Longhouse adherents. Generally the Christian Iroquois promoted social adjustment through the adoption of commercial agriculture and education in English; the Longhouse people championed the old ways, including hereditary chiefs, autonomy, and resistance to the Indian Act. Roughly a quarter of the reserve in 1890 identified with the Longhouse faith [see John Arthur Gibson*]. The Confederacy Council of some 75 chiefs became the only institution where members of the two traditions met regularly. By the turn of the century the chiefs had bridged their differences and were administering the Grand River territory effectively. Since council enjoyed widespread support, the Department of Indian Affairs did not interfere.

After leaving school, General had worked as a lumberjack in the Allegheny Mountains in western New York and Pennsylvania. An accident forced him to return and he began to farm near Millpond, in the vicinity of Ohsweken on the Six Nations Reserve. Enos T. Montour, a Delaware, recalled that “he had a good home and family, stockyard animals, and a sprinkling of cats and dogs.” He married the daughter of a Cayuga mother and a non-Indian father. His first language was Cayuga, and he participated actively in Longhouse ceremonies.

By World War I divisions were evident within council. The moderate, largely Christian element favoured continued cooperation with the Indian department and a degree of local autonomy, while the traditionalist group held to the system of hereditary chiefs and wanted more autonomy, based on the Six Nations’ historical claim to a special political status under a proclamation of Frederick Haldimand*, governor of Quebec, in 1784. A third faction, outside council and composed mainly of Iroquois soldiers in France, petitioned Ottawa in 1917 for an elected council.

That same year Louise Miller, the matron of the Young Bear clan of the Cayuga, installed General as its new hereditary chief, or deskaheh, on the Confederacy Council. A powerful orator, he would advance quickly: deputy speaker of council in 1918 and speaker in 1922. During the war the federal government had introduced military registration and conscription and after the armistice it had set land aside on the reserve for Iroquois veterans and granted them mortgages. Deskaheh and the majority of chiefs challenged both conscription and the suppression of council’s right to control land as intrusions on Iroquois sovereignty. Then, in 1920, the government amended the Indian Act to allow for compulsory enfranchisement and the removal (without consent) of an individual’s Indian status. This perceived infringement of civil liberty generated resentment and drew support to Deskaheh’s increasingly radical position.

Deskaheh pressured the government to review the Six Nations’ historical status, specifically their right to recognition as allies, not subjects, of the British crown, and hence to immunity from federal control. When council’s Canadian lawyers failed to obtain Ottawa’s agreement to such an investigation, in 1921 council hired George Palmer Decker, an American lawyer who had worked on legal issues for the Oneida in New York State. With funds raised by a finance committee of council, Deskaheh and Decker made a special trip to England that year. Deskaheh had come only a distant third in the popular vote held by council to select an Iroquois delegate to accompany the lawyer: he obtained 107 votes compared to 293 for Iroquois medical doctor J. A. Miller and 252 for David S. Hill, secretary of the Six Nation Agricultural Society. Yet, as Hill explained to Decker, council chose Deskaheh since the Longhouse people “are so suspicious of any person not of their faith, we thought it better to give way to one of them.” In England, Deskaheh and Decker learned that the Colonial Office considered the Six Nations to be British subjects, a decision later reinforced by Ontario’s courts. Hope for a federal investigation, however, was renewed following the election in December 1921 of William Lyon Mackenzie King* and the Liberals.

Deskaheh moved to strengthen his position. The upheaval on the Six Nations Reserve was reflected in the “small riot” that broke out there in April 1922. Although the King government reversed several policies of the previous, Conservative administration, including compulsory enfranchisement, the measures it introduced were no more palatable. In response to grievances voiced by both moderates and radicals at Six Nations – the government’s reduction of a native trust fund, introduction of laws “with a view to the dissolution of the Six Nations,” ignorance of council’s wishes to “improve education,” and mortgaging of reserve land – Charles Stewart*, the superintendent general of Indian affairs, offered in June to form a royal commission. After much difficult negotiation, including Iroquois threats to take the status issue to the newly formed League of Nations in Switzerland, the proposal was accepted, but the Department of Indian Affairs and council, now dominated by the radicals, both continued to press. In September, Deskaheh brought together the Longhouse chiefs, the pro-sovereignty Christian chiefs, and the Mohawk Workers Association, which sought total sovereignty. In December, without requesting council approval, the Royal Canadian Mounted Police raided the Six Nations territory to investigate reports of liquor manufacturing.

Not everyone in the Six Nations community supported Deskaheh and the radicals. Some resented the anti-British nature of their campaign. In July 1922 council secretary Asa R. Hill described the Cayuga chief as “an agitator of the worst type with no desire to come to any understanding. I am afraid that his actions will mean the breaking up of the confederacy.” Frederick Ogilvie Loft* of Toronto, a Mohawk chief and founder of the League of Indians of Canada, the country’s first pan-Indian political organization, also had doubts about Deskaheh’s confrontational approach. In a letter to Prime Minister King in December, he claimed that General, as council’s speaker, had been acting as a “dictator,” one who “occupies no position superior to any other Chief of the Six Nations. . . . He holds no mandate from the people of the Six nations to warrant his actions; indeed, contrary to the spirit of our Confederacy.” But by 1923 Deskaheh and his supporters had control of council; some moderates, irritated by the government’s actions, had joined them and others – like Hill, who was deposed as secretary – had been replaced.

After the RCMP raid, Deskaheh, convinced that the government was insincere, resolved to take the Six Nations’ case to the League of Nations. When deputy superintendent general Duncan Campbell Scott* learned of this move, he persuaded Stewart to locate a permanent RCMP detachment at Ohsweken. Negotiations then broke down, and Stewart set up a one-man inquiry instead. Andrew Thorburn Thompson*, a lawyer and former officer who had commanded Iroquois soldiers, was selected in March 1923 to head it.

Deskaheh and G. P. Decker arrived in London in August en route to Geneva. They lobbied for international recognition of the Six Nations as an independent state, under article 17 of the League’s covenant. Ties with Ottawa would be cut, the Indian Act would no longer control local government, the Six Nations would have their own laws, the chiefs would be in charge of funds, and council would hire its own employees and police. Decker remained only briefly in Geneva, where it proved difficult to obtain access to the League, but Deskaheh stayed for over a year, financially supported by a Swiss group, the Bureau International pour la Défense des Indigènes. One of Deskaheh’s great allies was René Claparède, a Swiss writer who championed the rights of indigenous peoples around the globe. Deskaheh’s efforts at the League proved fruitless. Although some countries appeared willing to discuss the issue, British objections to a review of what it regarded as a domestic Canadian matter were decisive.

During Deskaheh’s absence, his supporters at home boycotted Thompson’s hearings. Ready in November 1923 but not released for another nine months, Thompson’s report recommended the establishment of an elected council. Without consultation, the government deposed the hereditary council and, though voter participation was slight, a new council was elected in October 1924. Its existence deprived Deskaheh of his right to speak for the Six Nations.

Disillusioned and in poor health, he returned to North America in early 1925. At Six Nations, he had told George Decker, he expected to receive the same treatment as Gandhi in India, who was jailed but was eventually released “because his people had the power stronger then the British colonies, so they had to discharged him.” Deskaheh remained briefly with Decker in Rochester, and then moved to stay with his friend Chief Clinton Rickard on the Tuscarora Reservation in western New York, where he died. He was buried in the Upper Cayuga Longhouse cemetery at Six Nations. The speeches given on that occasion, in Iroquoian languages, urged those in attendance to continue Deskaheh’s work. The RCMP report of the event noted that, unless new leaders came forward, the agitation he had started would wither. The status issue resurfaced again at the League of Nations in 1929–30 but without effect. Deskaheh’s trip to the League of Nations in 1923–24 nonetheless marks the first attempt by North American First Nations to take their claims for sovereignty to an international forum.

The author wishes to thank Germaine General-Myke for genealogical information on the family of Levi General. As Deskaheh, General is the author of The redman’s appeal for justice, August 6, 1923 (London, 1923).

Canadian Museum of Civilization, Information management services (Hull, Que.), Acc. 89/55 (Sally M. Weaver coll.), box 468, file 30 (“Iroquois politics, 1847–1940,” 1975). LAC, RG 10, 2285, file 57169-1B, pt.3; RG 31, C1, 1871, 1881, 1901, Tuscarora Township, Ont. St John Fisher College, Lavery Library (Rochester, N.Y.), G. P. Decker papers. Ville de Genève, Suisse, Dép. municipal des affaires culturelles, Bibliothèque publique et universitaire, ms. fr. 3993 (Affaire “Six Nations”); ms. var. 1/15 (Les Six Nations iroquoises). Canadian annual rev., 1922: 267–68. Carl Carmer, Dark trees to the wind: a cycle of York State years (New York, 1949), 105–17. Deskaheh: Iroquois statesman and patriot ([Rooseveltown, N.Y., 1978?]). “Documents: introduction to documents one through five; nationalism, the League of Nations and the Six Nations of Grand River,” ed. Laurie Meijer Drees, Native Studies Rev. ([Saskatoon]), 10 (1995): 75–88. D. M. Johnston, “The quest of the Six Nations Confederacy for self-determination,” Univ. of Toronto, Faculty of law, Rev., 44 (1986): 1–32. Nellie Ketchukian, “Chief Deskaheh, George Decker and the Six Nations vs. the Government of Canada,” Iroquoian (Rochester), no.11 (fall 1985): 12–18; “The Decker papers II: Decker and Chief Deskaheh in Geneva, 1923,” Iroquoian, no.12 (spring 1986): 79–83. E. T. Montour, The feathered U.E.L.’s: an account of the life and times of certain Canadian native people (Toronto, 1973), 125–29. René Naville, Amérindiens et anciennes cultures précolombiennes (Genève, 1973), 144–49. Clinton Rickard, Fighting Tuscarora: the autobiography of Chief Clinton Rickard, ed. Barbara Graymont (Syracuse, N.Y., 1973), 58–68. Joëlle Rostkowski, “Deskaheh’s shadow: Indians on the international scene,” European Rev. of Native American Studies (Budapest), 9 (1995), no.2: 1–4; “The redman’s appeal for justice: Deskaheh and the League of Nations,” in Indians and Europe: an interdisciplinary collection of essays, ed. C. F. Feest (Aachen, Netherlands, 1987), 435–53. Annemarie Shimony, “Alexander General, ‘Deskahe,’ Cayuga-Oneida, 1889–1965,” in American Indian intellectuals; 1976 proceedings of the American Ethnological Society, ed. Margot Liberty (St Paul, Minn., 1978), 158–75. E. B. Titley, A narrow vision: Duncan Campbell Scott and the administration of Indian Affairs in Canada (Vancouver, 1986). S. R. Trevithick, “Conflicting outlooks: the background to the 1924 deposing of the Six Nations Hereditary Council” (ma thesis, Univ. of Calgary, 1998). Richard Veatch, Canadian foreign policy and the League of Nations, 1919–1939 (Toronto, 1975), 91–100, 201-2. Sally Weaver, “The Iroquois: the Grand River reserve in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, 1875–1945,” in Aboriginal Ontario: historical perspectives on the First Nations, ed. E. S. Rogers and D. B. Smith (Toronto, 1994), 182–212.

Cite This Article

DONALD B. SMITH, “DESKAHEH (Levi General),” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 15, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed January 1, 2026, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/deskaheh_15E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/deskaheh_15E.html |

| Author of Article: | DONALD B. SMITH |

| Title of Article: | DESKAHEH (Levi General) |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 15 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 2005 |

| Year of revision: | 2005 |

| Access Date: | January 1, 2026 |