BROCK, Sir ISAAC, army officer and colonial administrator; b. 6 Oct. 1769 in St Peter Port, Guernsey, eighth son of John Brock and Elizabeth De Lisle; d. 13 Oct. 1812 at Queenston Heights, Upper Canada. He never married, and there seems to be no real evidence to support the stories that have been told of a romantic attachment in Canada.

The Brock family were moderately wealthy. Isaac Brock evidently received his earliest education in Guernsey, where we are told he was remembered by his schoolfellows as an excellent swimmer and boxer, and by his family “chiefly for extreme gentleness.” When ten years old he was sent to school in Southampton, England, and subsequently studied for a year “under a French Protestant clergyman at Rotterdam, for the purpose of learning the French language.” As of 2 March 1785, at the age of 15, he obtained by purchase an ensigncy in the 8th Foot, the vacancy being caused by the promotion of his eldest brother, John, from lieutenant to captain in the same regiment. His early years in the service were spent in England. He became a lieutenant in 1790. Later that year he took advantage of the government’s authorizing a number of new independent companies to obtain the rank of captain by raising the men for one of them; he then exchanged into the 49th Foot, in which his captaincy was dated 15 June 1791. Thereafter his career was linked with the 49th. He joined it in Barbados, and did duty there and in Jamaica until 1793, when he was sent to England on sick leave. His nephew and biographer tells the story of how, soon after he joined the 49th, a professional duellist in the regiment forced a quarrel upon him. On being challenged Brock insisted that the exchange of shots should take place, not at the usual range, but across a handkerchief. The duellist refused, and in consequence left the regiment.

On returning to England Brock was employed in recruiting, and subsequently was in charge of recruits on the island of Jersey. He purchased a majority in the 49th as of 24 June 1795, and rejoined the regiment after it came back to England from the West Indies in July 1796. He became a lieutenant-colonel in the 49th by purchase on 25 Oct. 1797, and before the end of the year was the regiment’s senior lieutenant-colonel and in command of it. In August 1799 the 49th sailed with an expedition under Sir Ralph Abercromby directed against north Holland. In this campaign Isaac Brock had his first experience of battle. The 49th was part of a brigade commanded by Major-General (later Lieutenant-General Sir) John Moore. The advanced brigades, including Moore’s, landed at Den Helder on 27 August with slight opposition, and Abercromby’s force took up a strong position in which it beat off a French attack on 10 September. In these operations the 49th was not actively involved; the regiment was inexperienced and had been in poor condition when Brock took it over, and Moore was probably sparing it. It is interesting to speculate about the possible influence of this celebrated leader and trainer of troops on Brock; but no comment by Brock on Moore (or vice versa) seems to have survived. After the arrival of the Duke of York with additional British troops and a body of Russians, the allied force took the offensive. On 2 October, in the action called on the colours of British regiments Egmont-op-Zee (more properly Egmond aan Zee), the 49th was heavily engaged and did well. It was a disjointed battle fought among sand-dunes, ending in the enemy’s withdrawal. The 49th had 33 fatal casualties. Brock himself was slightly wounded, evidently by a spent ball. He wrote to his brother John, “I got knocked down shortly after the enemy began to retreat, but never quitted the field, and returned to my duty in less than half an hour.” The allies were now able to occupy Egmond and Alkmaar, but in another battle on 6 October in which the 49th were not present they were badly mauled. The Duke of York proposed a convention, allowing his army to embark freely for England; the French agreed, and thus ingloriously the campaign ended.

Early in 1801 Brock’s regiment was selected to be the main component of the military force carried in the fleet under Admiral Sir Hyde Parker which was dispatched to the Baltic to overawe Denmark. Brock, however, was not the senior army officer present; this was Lieutenant-Colonel William Stewart of the Rifle Corps (subsequently the Rifle Brigade), though only one company of that regiment was present. The troops’ intended role in the attack on Copenhagen was to assault, along with a body of bluejackets, the batteries built on piles in the harbour, notably the formidable Trekroner battery. This was likely to be an extremely costly operation. Fortunately, it was not attempted, chiefly because some of the leading vessels ran aground during the approach on 2 April so that the ships never silenced the batteries sufficiently to make it remotely practicable. The 49th were distributed among the ships of Vice-Admiral Lord Nelson’s squadron which attacked the Danish craft moored off Copenhagen. Brock himself was in the Ganges, though at the end of the action he visited Nelson’s flagship, the Elephant. The regiment shared the casualties of this bloody engagement, suffering 13 killed and 41 wounded.

When the 49th were ordered to Canada in 1802, Brock had still had comparatively little battle experience, having been present in two general actions, one of which was primarily a naval battle. The regiment embarked in June, and at Quebec on or about 25 August Lieutenant-Colonel Brock landed in the country with which his name was to be connected in history. The intention had apparently been to send the 49th to the far western posts, but they were kept in Montreal for the winter, and proceeded to Upper Canada in the spring of 1803, the headquarters going to York (Toronto), with a wing of the regiment under the junior lieutenant-colonel, Roger Hale Sheaffe*, at Fort George (Niagara-on-the-Lake, Ont.).

Brock at once encountered the problem of desertion, which was particularly serious at posts close to the American border. In the summer of 1803 seven soldiers deserted from York in a stolen boat. Brock set off across Lake Ontario in pursuit with a party of the 49th in a bateau. At Fort George he sent an officer’s party by boat along the American shore of the lake to search for the deserters, while he himself turned back along the Canadian shore in case they were coasting it. The other party in fact apprehended the men on American soil, with the assistance of one or more Indians, and they were brought back to Canada – a violation of American law, which however seems to have led to no protest. Later the same season the officers at Fort George got wind of a conspiracy, said to have been brought on by the severity of Sheaffe, to imprison the officers and desert to the United States. Before taking any action, the officers thought it well to send particulars to Brock at York. He at once crossed the lake in a schooner, and arrived at the fort gate alone. Finding that the guard turned out to receive him was commanded by the sergeant and corporal reported to him as the ringleaders, he ordered them into confinement on the spot, ending the conspiracy at a stroke. The conspirators and the deserters lately apprehended were shipped off to Quebec, where after court martial seven of them were shot the following March.

Brock was promoted colonel as of 30 Oct. 1805, and about the same time went home on leave. While in England he made detailed recommendations for dealing with desertion in Canada, arguing that a veteran battalion formed of reliable old soldiers should be organized to occupy the border posts. His advice was acted on shortly; and this expedient was resorted to again a generation later, when the Royal Canadian Rifle Regiment was formed in 1840–41 on Brock’s principles for the same purpose, and did duty until the withdrawal of the British troops from central Canada in 1870. While Brock was still on leave there was apprehension of war with the United States, and he decided of his own volition to cut his leave short and return to his post. He left London for the last time on 26 June 1806. In September he found himself in temporary command of all the troops in Canada, with headquarters at Quebec, and this situation lasted until Sir James Henry Craig arrived to take up the appointments of governor-in-chief and commander of the forces in October 1807.

During this period of authority Brock worked with characteristic energy to improve the defences of the country. His chief care was to strengthen the fortifications of Quebec, the position on which communication with Britain ultimately depended. He reconstructed the walls facing the Plains of Abraham, and built an elevated battery mounting eight heavy guns in the temporary citadel made during the American Revolutionary War, with the object of commanding “the opposite heights,” that is, those south of the river. This came to be known as “Brock’s Battery,” a name which Craig changed on his arrival to the King’s Battery. Brock’s activity brought him into difficulty with the civil government of Lower Canada (then administered by Thomas Dunn) on several issues: civilian encroachments on military lands; the use of waste land near the Jesuit college in Quebec for drill; responsibility for the cost of the Indian Department; Brock’s request for civil labour to work on the fortifications; and his desire that part of the militia should be called out for training, and volunteer corps authorized and armed. The colonel got little satisfaction on any of these questions. One useful reform which lay entirely within his military competence Brock was able to carry out. Late in 1806 he gave orders that the “marine department” on the lakes and rivers of the Canadas should be under the superintendence of the deputy quartermaster general. The Provincial Marine’s chief function was providing transport service for the army, but from this time on it was increasingly developed as a force capable of naval action in case of war. Under one assistant quartermaster general at Kingston and another at Amherstburg it was more effectively administered than ever before, and it seems fair to say that Brock’s action in 1806 was largely responsible for the existence of the force that six years cater gave him naval command of the Great Lakes and thereby made possible his successful defence of Upper Canada.

Craig after his arrival made Brock a brigadier-general (an appointment rather than a rank, shortly confirmed from England) and placed him in command at Montreal. A few months later he returned to Quebec, where he remained until July 1810, when Craig sent him to take charge in Upper Canada. This command he retained until his death. He frequently complains in his letters of being left idle in Canada (“buried in this inactive, remote corner”) while the main body of the British army is winning laurels in Europe. But the danger of war with the United States (and, he himself said, the possibility of a French-Canadian rising in the event of a French invasion) kept him where he was. Finally, early in 1812, letters from London indicated readiness to give him employment in Europe, but by then the aspect of affairs in North America was very threatening; and on 12 February Brock wrote, “I beg leave to be allowed to remain in my present command.” On 4 June 1811 he had been promoted major-general; the same extensive block promotion brought this rank to Sheaffe as well. In October 1811 Francis Gore*, the lieutenant governor of Upper Canada, left for England on leave (he did not return until the war with the United States was over); Brock now became “president” and administrator of the government of the province. For the final year of his life he headed both the military command and the civil government.

Financial disaster had struck the Brocks in 1811. The general’s brother William was senior partner in a London firm of bankers and general merchants which failed. William had advanced Isaac some £3,000 to purchase his commissions in the 49th, with no intention of ever requiring payment; but the loans had been entered, without Isaac’s knowledge, in the firm’s books. He now unexpectedly found himself faced with a demand for payment which he could not meet, but he made the whole of his new civil salary over to his brother Irving, to begin discharging the debt or to relieve distress in the family, as he thought best.

In February 1812, under the shadow of impending war with the United States, Brock met the provincial legislature. He found it less than fully cooperative; it refused to suspend habeas corpus, and the new militia act it provided was made effective only until the end of the next session. It did, however, permit the organization on a voluntary basis within each paper militia battalion of two “flank companies” which might train for up to six days a month (though no provision was made for pay). Volunteers came forward willingly, and these companies, already organized and to a slight extent trained, were Brock’s first resource for strengthening his small force of regulars when war broke out.

In December 1811 Brock had explained his war plans in a letter to Lieutenant-General Sir George Prevost, who had become governor-in-chief and commander of the forces in September. Emphasizing the importance of the cooperation of the Indians, he said that to obtain this it would be vital to seize Michilimackinac (Mackinac Island, Mich.) and Detroit (Mich.) at the outset of hostilities; he advocated in effect a bold policy of limited local offensives. The United States declared war on 18 June 1812. There were then about 1,600 British regular troops in Upper Canada, including the 10th Royal Veteran Battalion (not well fitted for field operations) and the Royal Newfoundland Regiment, chiefly employed with the Provincial Marine; the effective force consisted mainly of the 41st Foot and a company of the Royal Artillery. As soon as news of the outbreak reached him, Brock reinforced the Niagara frontier from York and went there himself. The weakness of his force, combined with letters from Prevost advising restraint lest hostile action should unite the divided American people, caused him for the moment to curb his natural impatience to take the offensive. In a succession of letters to Captain Charles Roberts, commanding at Fort St Joseph (St Joseph Island, Ont.) at the head of Lake Huron, he showed an untypical vacillation; but the last of them authorized Roberts to use his own judgement as to whether or not to attempt an attack on Michilimackinac. Roberts made the attack and it succeeded, and, as Brock had anticipated, this small early victory brought the Indians of the Upper Lakes region to the British standard.

On 12 July Canada was invaded on the Detroit frontier by Brigadier-General William Hull. There was now no doubt of American aggressive intentions, and Brock plunged into energetic counter-measures. The omens, however, were unfavourable. Hull’s invasion, and the proclamation he issued, demoralized the Canadian militia along the Detroit, and they deserted in numbers, some going over to the enemy. Brock’s counter-proclamation of 22 July was confident in tone, but it revealed his inner doubts: even if the province should be overrun, he declared, there was no question of its being “eventually abandoned” by the British government. He again met the Upper Canada legislature on 27 July, and again found it lukewarm; it was still unwilling to suspend habeas corpus. On the 29th he wrote to the adjutant general at headquarters in Montreal: “My situation is most critical, not from anything the enemy can do, but from the disposition of the people – the population, believe me is essentially bad – A full belief possesses them all that this Province must inevitably succumb – This prepossession is fatal to every exertion – Legislators, Magistrates, Militia Officers, all have imbibed the idea, and are so sluggish and indifferent in their respective offices that the artful and active scoundrel is allowed to parade the Country without interruption, and commit all imaginable mischief. . . .”. “What a change an additional regiment would make in this part of the province! Most of the people have lost all confidence – I however speak loud and look big. . . .”. Patriotic Canadian historians have sometimes been reluctant to recognize this aspect of the situation. It is, however, essential to an adequate assessment of Brock. Many commanders would have allowed the current despondency to discourage them into adopting a supine defensive attitude. Brock took the offensive.

The British troops on the Detroit still held the fort at Amherstburg. Brock informed Prevost that he proposed to collect a force at Long Point on Lake Erie to relieve Amherstburg. He sent thither 100 militia volunteers from York, and followed them himself. Colonel Thomas Talbot* had much difficulty with the militia in and around his settlement north of Lake Erie, but finally obtained a fair number of volunteers. On 8 August Brock embarked his small striking force of about 300 men (only about 50 of whom were regulars) at Long Point, and after a stormy voyage they reached Amherstburg on the 13th. Hull, discouraged by the threat to his communications along the Lake Erie shore posed by the Provincial Marine, Indians, and British detachments, had already withdrawn from Canada to Detroit. Brock’s total force was about 1,300 men, of whom 400 were militia and 600 were Indians. Hull had something over 2,000, including a detachment of about 500 he had sent out to protect an approaching supply column; and Fort Detroit was well armed with artillery. Brock’s decision to attack across the Detroit River on 16 August was bold. His first intention was to take up a defensive position on the American side and offer battle in the open, but apprehension of trouble from the detachment in his rear led him to advance at once upon the fort, which was being fired on by a battery on the Canadian shore. The mere threat of attack was enough; Hull surrendered Detroit and his army, with 35 guns and other stores which were very useful for the defenders of Upper Canada.

In a private letter Brock described the appreciation that led to his audacious action: “Some say that nothing could be more desperate than the measure, but I answer that the state of the Province admitted of nothing but desperate remedies. I got possession [through the capture of an American vessel by the Provincial Marine] of the letters my antagonist addressed to the Secretary at War, and also of the sentiments which hundreds of his army uttered to their friends. Confidence in the General was gone, and evident despondency prevailed throughout.” He added that he crossed the river against the advice of his colonels; “it is therefore no wonder that envy should attribute to good fortune what in justice to my own discernment, I must say, proceeded from a cool calculation of the pours and contres.”

There seems no doubt that the presence with Brock of a large number of Indians contributed materially to the moral deterioration of Hull and his force. Brock had assisted the process by remarking in a letter in which he demanded Hull’s surrender that, while he did not propose to “join in a war of extermination,” the Indians would be “beyond controul the moment the contest commences.” (In fact, at both Michilimackinac and Detroit the Indians’ conduct was beyond reproach.) A relationship of mutual confidence and regard had been established between Brock and the Shawnee chief Tecumseh, who was the effective leader of the Indians at Detroit; it was reflected in the fact that Brock is said to have presented to Tecumseh his sash (which Tecumseh modestly passed on to a senior chief), while Tecumseh gave Brock his sash in exchange. This story has been questioned, but the presence of an “arrow” sash among the general’s uniforms as received by his family seems to provide rather strong presumptive evidence for it.

In Upper Canada the effect of the dramatic and almost bloodless victory at Detroit was electric. Brock wrote to his brothers on 3 September, “The militia have been inspired by the recent success with confidence – the disaffected are silenced.” No one now doubted that the country could be defended. From Detroit Brock hastened back to the Niagara front. Prevost, he heard, had negotiated with Major-General Henry Dearborn, commanding the American forces in the eastern sector, a temporary agreement by which both sides in that region would refrain from offensive action. This resulted from a suggestion by the former British minister in Washington, D.C., Augustus John Foster, now at Halifax, N.S., who on receiving news of Britain’s withdrawal of the orders in council interfering with American trade – orders in council which had been one cause of the war – had set about trying to restore peace. President James Madison refused these overtures, and Brock complained that the abortive “armistice” had merely allowed tire enemy to bring up more troops to the frontier.

The chief menace was now on the Niagara. Here, as along the whole frontier, Brock’s problem was defending a long line with inadequate forces, always uncertain where the Americans might strike. On 12 October his brigade-major, Thomas Evans*, crossed the river at Queenston under a flag of truce and saw on the American side boats in readiness for crossing. Returning to Brock at Fort George he argued that an attack at Queenston was imminent. It seems likely that Brock was not fully convinced, for he remained at Fort George. Before daylight on the 13th, however, gunfire from the direction of Queenston announced that an attack was in progress. Brock, who probably had slept in his clothes, at once mounted and rode hard towards the scene of action, followed at a short interval by his two aides-de-camp, one of whom was Lieutenant-Colonel John Macdonell (Greenfield), attorney general of the province. The general’s idea was presumably to make a personal assessment of the situation, for he does not seem to have left orders for the Fort George garrison to move. The flank companies of the 3rd York militia battalion (the “York Volunteers”) were stationed at a battery at Brown’s Point, about two miles below Queenston. After brief hesitation their commander, Captain Duncan Cameron*, marched them towards the sound of the guns. John Beverley Robinson*, a subaltern in the Volunteers, in a letter written the next day, describes how Brock, overtaking them, “waved his hand to us, and desired us to follow with expedition, and galloped on with full speed to the mountain.”

Brock’s own 49th Foot had arrived from the lower province to reinforce Upper Canada in August, and its grenadier and light companies, along with militia companies from Lincoln and York, were opposing the enemy landing in Queenston, supported by a three pounder field-piece and another gun on the river bank below. The Americans had suffered considerably and when Brock galloped into the village the situation must have seemed fairly well in hand. The early stages of the battle were not well documented, but it appears that the 49th light company had been posted on the heights above Queenston, and was called down before Brock’s arrival (or, less probably, by the general himself) to join in the fight below. Brock rode up to the “redan” battery (one gun) part way up the hill, and there was surprised by the appearance of enemy troops above him. This was a force under Captain (later Major-General) John Ellis Wool, which had found a way up by a “fisherman’s path.” Brock and the gunners abandoned the battery and hastily retreated down the hill. Realizing the importance of evicting Wool from his commanding position before he could be reinforced, the general collected the troops near by and led them up the slope on foot. Wool’s account, which is not very clear, indicates that the Americans were driven back some distance, but at this moment Brock – six feet two and a splendid target – fell a victim to an enemy sharpshooter. As the bullet-hole in his extant coatee proves, he was struck full in the heart and must have died without a word. This, indeed, is the evidence of George Stephen Benjamin Jarvis*, a Canadian volunteer with the 49th, who was beside him. The attack ebbed back down the hill.

At some point the general had uttered words which at once became famous. The York Gazette four days later gave “Push on brave York Volunteers” as “the last words of the dying hero,” the Volunteers “being then near him.” But as Robinson’s letter amply proves, the York Volunteers were not yet on the field when Brock fell; they entered Queenston as his body was being carried back. A more plausible account is given in a letter written at Brown’s Point on 15 October, and published in the Quebec Mercury of 27 October: “The York volunteers to whom he was particularly partial, have the honor of claiming his last words[;] immediately before he received his death wound he cried out, to some person near him to push on the York volunteers, which were the last words he uttered.” Another possibility is that the words were said when he passed the Volunteers on the road, as described by Robinson; but the fact that the Mercury letter was itself pretty clearly written by one of the Volunteers makes this rather unlikely.

Brock’s death left Macdonell the senior officer on the ground. He proceeded to lead the Volunteers and the other troops at hand in another attack against the heights. But Macdonell’s horse was shot under him, he himself was mortally wounded, and this attack too failed. Brock’s body was left in a house in Queenston, and the survivors of the defending force retired to the north end of the village. The battle seemed lost. Early in the afternoon, however, General Sheaffe came up from Fort George with fresh troops including several companies of the 41st and some field-guns. The Americans in possession of the heights were left without support from across the river. Following in the footsteps of a force of Indians under John Norton*, which had arrived earlier and was harassing the enemy, Sheaffe’s men climbed the escarpment some distance inland, advanced along the summit, and destroyed the invading force completely, taking nearly 1,000 prisoners. Brock was amply avenged.

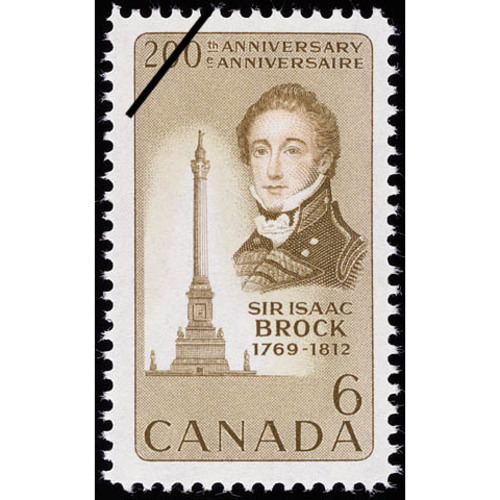

Brock never knew that four days before his death the Prince Regent had recognized his victory at Detroit by appointing him an extra knight of the Order of the Bath. He and Macdonell were buried with ceremony on 16 October in a bastion of Fort George, an American salute across the river echoing the British minute-guns. In 1824 they were reburied under an imposing monument on the summit of Queenston Heights. This was blown up in 1840, supposedly by a “border ruffian” named Benjamin Lett*. The memory of Brock was still extraordinarily strong in Upper Canada, and on 30 July in the same year 8,000 people from all parts of the province met at Queenston to plan an even more striking memorial. This ultimately took the form of the lofty column, “the stateliest monument that has been raised to an individual anywhere in Canada,” which still dominates the romantic battlefield where Brock fell. In London he is commemorated by a modest memorial voted by parliament in St Paul’s Cathedral.

Isaac Brock was one of the people to whom it is given to change the course of history. But for the presence in Upper Canada in the summer of 1812 of this able and magnetic general officer (and a single battalion of British regular infantry) the province would certainly have fallen to the United States; whether or not it was recovered would have depended on the determination of the British government. As it was, the morale of the community never fell again to the point it had reached before it was revived by Brock’s daring stroke against Detroit. The York Gazette, reporting his death, said, “Inhabitants of Upper Canada, in the Day of Battle remember BROCK.” And indeed it seems hardly too much to say that Brock’s spirit continued to animate the people of the province for the rest of the war. His action at Detroit, we have seen, was criticized as being unduly rash; and the same has been said of his last charge at Queenston Heights. Boldness was his way; but boldness almost always succeeds when the enemy is ill prepared and irresolute, and it saved Upper Canada in 1812. As Robinson said long afterwards, but for the misfortune of a well-placed bullet his attack at Queenston might have succeeded too. His personality was both attractive and compelling, and the memory of it combined with the dramatic success achieved during the brief four months of his war leadership and the manner of his death to make him warmly remembered as a Canadian hero.

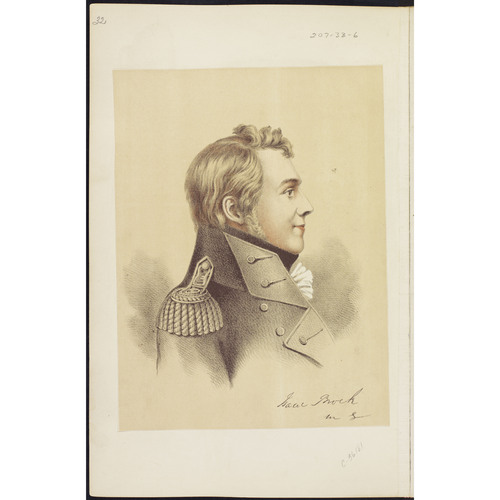

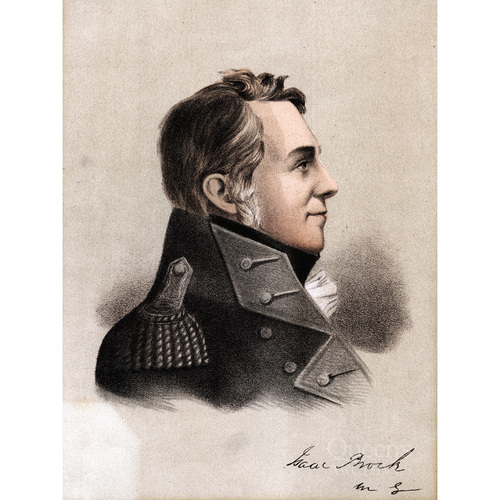

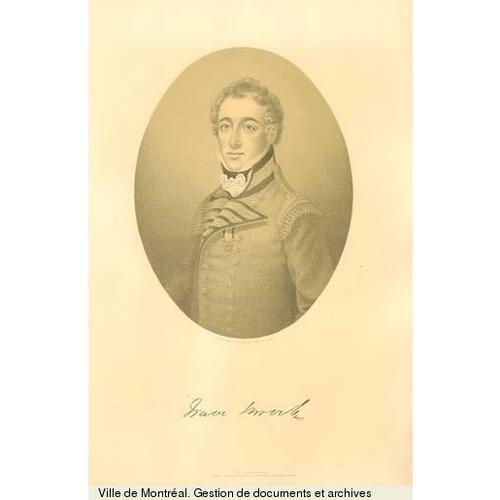

[What appears to be the only authentic portrait of Brock is a pastel profile now in the possession of Captain M. H. T. Mellish of St Peter Port, Guernsey, who inherited it from Miss Edith Tupper. It has been attributed to James Sharples, but seems almost certain to be the work of William Berczy. It has often been reproduced and copied in various forms; it indicates that he was a remarkably handsome man. (A picture which has been published as representing Brock, “from a miniature in possession of Miss Sara Mickle,” seems to the present writer likely to be a portrait of Sir George Gordon Drummond*.) The uniform in which Brock was killed, formerly owned by his heirs in Guernsey, is in the Canadian War Museum, Ottawa. It includes the arrow sash which may be Tecumseh’s. Another uniform of Brock’s, with a sword and a military sash, is in the McCord Museum at McGill University. Both coatees carry the lace of a brigadier-general; it seems possible that Brock never obtained a major-general’s uniform after his promotion in 1811.

The power of the Brock legend in Canada is reflected in the fact that no important known documents concerning his Canadian activities seem to have escaped publication. It is reflected also in the number of biographies of Brock that have been written in Canada. Nevertheless, there is no extended modern biography. Virtually everything that has been written about him, including the present article, is heavily indebted to the book edited by his nephew, Ferdinand Brock Tupper, The life and correspondence of Major-General Sir Isaac Brock . . . (London, 1845), which appeared in an enlarged 2nd edition in 1847. Apart from incorporating family information, this book has the special importance of publishing a large number of letters from and to Brock, of which the originals in many cases appear to have perished. Of the Canadian books, the longest are D. B. Read, Life and times of Major-General Sir Isaac Brock, K.B. (Toronto, 1894), and [Matilda] Edgar, General Brock (Toronto, 1904). Neither is completely satisfactory. Of the shorter biographies, four are meant for school use: W. R. Nursey, The story of Isaac Brock, hero, defender and saviour of Upper Canada, 1812 (Toronto), first published in 1908, which contains a large admixture of imagination; H. S. Eayrs, Sir Isaac Brock (Toronto, 1918); T. G. Marquis, Sir Isaac Brock (Toronto, n.d.), which is very slight; and D. J. Goodspeed, The good soldier; the story of Isaac Brock (Toronto, 1964). W. K. Lamb, The hero of Upper Canada (Toronto, 1962), is brief but perceptive.

Among collections of documents, Doc. hist. of campaign upon Niagara frontier (E. A. Cruikshank), vols.3–5, is essential though often badly transcribed. Valuable also is the same editor’s Documents relating to the invasion of Canada and the surrender of Detroit, 1812 (Ottawa, 1912). [Isaac Brock], “Some unpublished letters from General Brock,” ed. E. A. Cruikshank, OH, 13 (1915): 8–23, contains little of importance. Select British docs. of War of 1812 (Wood) is important, though internal evidence indicates that in some cases the documents were transcribed not from the originals but from other printed collections. Of more incidental importance are [Horatio Nelson], The dispatches and letters of Vice Admiral Lord Viscount Nelson, ed. N. H. Nicolas (7v., London, 1845–46), 4; Norton, Journal (Klinck and Talman); and Ten years of Upper Canada in peace and war, 1805–1815; being the Ridout letters, ed. Matilda Edgar (Toronto, 1890).

Of many general secondary books and articles the following may be mentioned: Andre, William Berczy; Pierre Berton, The invasion of Canada, 1812–1813 (Toronto, 1980), and Flames across the border, 1813–1814 (Toronto, 1981); J. W. Fortescue, A history of the British army (13v. in 14, London, 1899–1930), 4, pt.ii; 8; Hitsman, Incredible War of 1812; A. T. Mahan, Sea power in its relations to the War of 1812 (2v., London, 1905), still the best strategic study; F. L. Petre, The Royal Berkshire Regiment (Princess Charlotte of Wales’s), this being the former 49th Foot (2v., Reading, Eng., 1925); Dudley Pope, The great gamble (London, 1972), concerning the battle of Copenhagen; [C. P. Stacey], “The defence of Upper Canada, 1812,” Introduction to the study of military history for Canadian students, ed. C. P. Stacey (4th ed., Ottawa, 1955), 65–74; L. E. Buckell, “British uniforms in the American War of 1812,” Soc. for Army Hist. Research, Journal (London), 28 (1950): 29–30, corrected in details in N. P. Dawnay, “The staff uniform of the British army, 1767 to 1855,” Soc. for Army Hist. Research, Journal, 31 (1953): 64–84; Ludwig Kosche, “Relics of Brock: an investigation,” Archivaria (Ottawa), no.9 (winter 1979–80); 33–103.

Other sources include: Kingston Gazette, 19 May, 29 Aug., 24, 31 Oct. 1812; Quebec Mercury, 27 Oct. 1812; Times (London), 23 Nov. 1812; York Gazette, 17 Oct. 1812; G.B., WO, Army list, 1786, 1791, 1795–96, 1812. c.p.s.]

Cite This Article

C. P. Stacey, “BROCK, Sir ISAAC,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 5, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed December 13, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/brock_isaac_5E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/brock_isaac_5E.html |

| Author of Article: | C. P. Stacey |

| Title of Article: | BROCK, Sir ISAAC |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 5 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1983 |

| Year of revision: | 1983 |

| Access Date: | December 13, 2025 |