Source: Link

OVERHOLSER (Oberholser), JACOB, settler and convicted traitor; b. c. 1774 in the American colonies; m. Barbara – , and they had four children; d. 14 March 1815 in Kingston, Upper Canada.

Jacob Overholser led a life that in most respects was singularly unexceptional. A simple man, probably illiterate, he immigrated to Upper Canada with his wife and children about 1810 and settled in Bertie Township, where in 1811 he bought a farm. From all accounts he appears to have worked hard, made friends with his neighbours, and enjoyed a moderate degree of prosperity. Unlike officials at York (Toronto), the mercantile élite of the Niagara peninsula was not over concerned by the presence of American settlers, and Overholser seems to have met with the approval of John Warren of Fort Erie, the pre-eminent man of the township, and his family.

The War of 1812 shattered Overholser’s life. The peninsula was the scene of heavy fighting throughout the war and, as opposing armies moved back and forth, civilian life was altered in their wake. Without a strong and lasting military presence by either army, order often quickly broke down. A regrettable, but probably a natural enough, consequence was that some seized on this instability to settle private grudges or further personal ends. A recent American immigrant such as Overholser was a likely target for the vengeful.

Although the exact time frame is not clear, Overholser had problems with a set of louts – principally members of the Anger family – whose actions towards him were tinctured with malice. After the retreating American army burned Niagara (Niagara-on-the-Lake) on 10 Dec. 1813, these men threatened to take his land and set fire to his buildings, and on one occasion several of them stole four horses from his barn. About 20 December Overholser, together with Thomas Moore, a Quaker neighbour, approached Major-General Phineas Riall* to seek redress. The general referred the case to the Queenston merchant and magistrate Thomas Dickson*, who ordered the animals returned. The Angers then charged that during the American occupation Overholser had accompanied the enemy when members of their family were taken prisoner. The charge was serious and Dickson had no choice but to refer the matter back to Riall and ask John Warren Jr, also a magistrate, to investigate.

Extant documents relating to Overholser’s actions from about the 1st of December 1813 to 26 Jan. 1814 are so fragmentary and elliptical as to render impossible a full reconstruction of events. Before Dickson, Overholser’s accusers had charged that on or about 1 Dec. 1813 he had been seen “in Company with the Americans” when Benjamin Clark and two members of the Anger family were captured. The prisoners were removed to Black Rock (Buffalo), N.Y., and the following day Overholser testified against them for having broken the conditions of a previous parole granted them by the American forces. Warren’s inquiry established that the basic outline of events was true but that Overholser had been compelled by the Americans to accompany them and carry a rifle. Warren concluded that there was no substance to the charge and that the whole episode amounted to “Nothing more than an ill Disposition” by the Angers towards Overholser. Moore interjected that even if the charges were true, the Angers’ crime in stealing Overholser’s horses was the greater. Obviously alarmed by the possibility of charges against them, the Angers then suggested that they would return Overholser’s property if the matter was dropped. Warren agreed “and there it was supposed to end.” However, the Angers, a thuggish lot, took the first opportunity – the absence of Dickson and Riall – to revive their charges against Overholser, and another magistrate, apparently unfamiliar with the case, ordered him jailed. Towards the end of January 1814, through the intercession of Riall, Moore secured bail for Overholser, an extraordinary departure in circumstances involving possible charges of high treason. Later, when ordered to appear in court, Overholser voluntarily surrendered himself to the sheriff.

Overholser’s situation was serious but his prospects were hopeful. The charges seemed to lack substance, his accusers were a disreputable set, and Dickson, Warren, and Riall supported him. But Overholser’s fate did not turn on legal niceties; his story became intertwined with, and inseparable from, the grim determination of military and civil authorities to overawe disaffection by exemplary punishment. The genesis of this resolve deserves an explanation.

The experience of the American revolution and the examples of the French revolution and the Irish rebellion of 1798 had made the Upper Canadian élite highly suspicious of non-loyalist American settlers, anxious about political opposition, and inflexible on the meaning of loyalty. The rise of a parliamentary and extra-parliamentary opposition associated with William Weekes, Robert Thorpe*, and Joseph Willcocks exacerbated these anxieties. Although, in large part, the parliamentary opposition drew its strength from matters of local concern, it took its political language from a transatlantic whig tradition rooted in the 18th century which emphasized constitutional liberty, civil rights, and the prerogatives of elected assemblies. The heyday of the opposition, the legislative sessions of 1812, brought these ideals into conflict with the exigencies of war. Administrator Isaac Brock had grave doubts about the effect of a largely American population upon Upper Canada’s security. He feared that the war might be lost not from “any thing the enemy can do, but from the disposition of the people.” In an address to the House of Assembly in which he recalled the experience of Great Britain between 1792 and 1795, a period sometimes known as the “White Terror,” Brock sought sanction for emergency measures such as a suspension of habeas corpus to secure the province “from private Treachery as well as from open dissaffection.” These proposals violated sacred whig principles and the assembly under the leadership of men such as Willcocks and Abraham Markle* rejected them.

Brock’s suspicions about the popular mood were further confirmed by the reaction in the western areas of the province to American brigadier-general William Hull’s proclamation of 12 July 1812. The problem of disaffection was kept in abeyance by the military victories at Detroit and Queenston Heights, but throughout 1813 the situation steadily deteriorated. Following the American capture of York on 27 April 1813, an event that led to an outbreak of disorder and the voicing, albeit in a coarse manner, of explicit egalitarian and democratic sentiments, the concern for constitutionalism on the part of the élite all but collapsed [see Elijah Bentley]. Little more than a week later prominent men of the Niagara peninsula such as James Crooks* and Robert Nichol* petitioned Major-General John Vincent* to take measures sufficiently severe to quell the traitorously inclined, and on 28 June judge William Dummer Powell* opined that in the event of a military disaster it would be difficult for the loyal to “keep down the Turbulence of the disaffected who are numerous.” In July Governor Prevost authorized the formation of general courts martial in cases requiring “an immediate example.” When on 3 August the influential York merchant William Allan* charged certain people with seditious behaviour during the occupation, Administrator Francis de Rottenburg* instructed the acting attorney general, John Beverley Robinson*, to investigate the instances of “dangerous and treasonable inclinations.” Several days later the Executive Council recommended increased military surveillance and the detention of suspects, and the report of the committee appointed by Robinson to inquire into the situation at York urged the need to make examples of the disaffected. It was probably just this change in the constitutional climate of the province that prompted the treason of Willcocks and Markle in the summer of 1813.

As the military situation west of York deteriorated, the civil situation became even more acute. On 13 November 18 marauders were captured in Norfolk County. Rottenburg ordered Robinson to take prompt measures to bring the renegades to trial and advised him that a special commission – the instrument used in extraordinary circumstances to summon the full majesty of the law – would be appointed. George Gordon Drummond*, Rottenburg’s successor, issued the commission on 14 December for the trial of all persons accused of treason, with special concern for the London and Home districts. Uppermost in Drummond’s mind was the need “to make examples” immediately. Robinson, however, proceeded slowly. The peculiarities of the law regarding high treason required him to take great care to avoid errors. Moreover, he hoped to avoid departing from normal civil procedures because executions “by military power would have comparatively little influence – the people would consider them as arbitrary acts of punishment.”

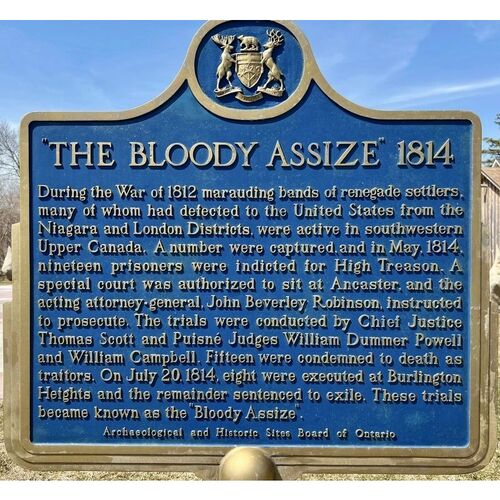

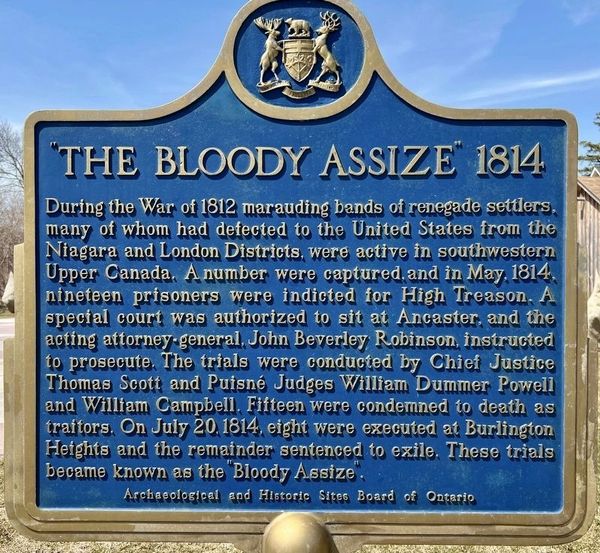

When Robinson reported to Drummond on 4 April 1814 Jacob Overholser was among the men to be charged. Drawn into a web of events beyond his own making, he was now to be lumped together with men who were avowed traitors and who had actually taken up arms. The site of the great show trial of Upper Canadian history was Ancaster. The court opened on 23 May with the three justices of the Court of King’s Bench, Thomas Scott*, William Campbell*, and Powell, presiding. Three of the associate judges, Richard and Samuel Hatt and Thomas Dickson, were drawn from the local magistrates, and the 17-man grand jury included some of the area’s leading merchants and office holders, notably James Crooks, Robert Nelles*, and Samuel Street*. In all the jury found true bills against 21 prisoners and 50 others. Overholser was indicted on 24 May and two days later decided on John Ten Broeck and Bartholomew Crannell Beardsley* as his counsel. His trial took place on 8 June before Powell, the Hatts, and Dickson. He pleaded not guilty, a petit jury of 12 was picked, and the witnesses appeared – four for the crown (three Angers and Clark) and five for the defence, including Dickson and Warren. Unfortunately for Overholser, his Quaker friend Thomas Moore refused to take the required oath and could not be sworn.

Overholser was charged with a branch of high treason known as adherence to the enemy; his specific act was alleged to have been carrying arms and assisting the enemy in making prisoners of the king’s subjects. According to Robinson’s summary of the case and Powell’s bench notes on the trial, the evidence against him was as follows. On or about 1 Dec. 1813 Overholser had accompanied an “armed party of the Enemy” to the homes of his neighbours, Clark and the Angers, who were then made prisoners. Overholser stood armed guard over them before they were taken to Black Rock. The following day he “voluntarily” appeared at Buffalo claiming that at some point before their capture Clark and the Angers had broken the terms of their parole with the American army by making him a prisoner. The ensuing day at Black Rock he attended the examination of the prisoners, who were then sent to Fort Niagara (near Youngstown), N.Y. Overholser’s defence was developed along two lines. First (and this was undoubtedly the work of his counsel), he argued that since he was an American citizen the withdrawal of the protection of British forces had absolved him of the allegiance he owed the king. Thus, his action constituted only “a Trespass against the Individuals and not Treason,” according to this act’s definition by statute. Secondly, he repeated his testimony before Warren to the effect that he had been “impelled to join the Enemy by Apprehension of Danger to himself.” But Powell noted that his defence “was not sustained by Evidence” and that the charge of treason “was fully and satisfactorily proved by the Testimony.” From the bare outline of the trial in the minute-book it seems that the jury had some difficulty reaching a verdict. No doubt the testimony of John Warren Jr that the prisoner was a “quiet, inoffensive Man, always obedient to the requisitions of the Magistrates” had something to do with its discussion. The deliberations lasted for an hour and a half before Overholser was pronounced guilty.

Overholser was not alone in his misfortune: of the 21 men tried, 17 were convicted. The penalty for high treason was harsh and calculated to have a “strong and lasting” impact upon the “Public Mind.” On 21 June Scott read the sentence to the convicted men: “You are to be drawn on Hurdles to the place of execution where you are to be hanged by the neck, but not until you are dead, for you must be cut down while alive and your entrails taken out and burnt before your faces, Your Heads then to be cut off, and your bodies divided into four quarters, and your Heads and quarters to be at the Kings disposal.” Since Drummond and others believed that “many examples were not necessary to convince the Province that Treason will meet with its due reward,” the thorny question was whom to pardon. Robinson provided him with detailed recommendations on each of the cases. As far as Overholser was concerned, Robinson termed him an “ignorant man . . . of considerable property – a good farmer . . . not a man of influence or enterprise, and it is thought acted as he did from motives of personal enmity to the persons [the Angers and Clark] . . . who are not of themselves men of good characters.” The proper objects of punishment, he noted, were not unfortunates such as Overholser, but notorious offenders. A petition for clemency signed by 95 residents of Bertie Township claimed that Overholser was “an honest peaceable Sober and Industrious Inhabitant.” John Warren Jr’s name headed the list of signatories and he forwarded the petition observing that Overholser was “worthy of every indulgence.”

On 9 July Drummond approved Robinson’s recommendations and respited the executions of nine men, one of whom was Overholser; the eight selected for execution were hanged, until dead, at Burlington Heights (Hamilton) on 20 July. Overholser was sent immediately to York and then forwarded to Kingston where he languished in a military jail awaiting confirmation of a royal pardon and transportation to Quebec and banishment. On 14 March 1815 he died of typhus fever. At the time of his death his farm was not fully paid for. A dispute over ownership ensued but his wife continued to reside there at least until January 1818. Ultimately his 196 acres were vested in the crown and sold in 1821.

The trial at Ancaster has been dubbed the “Bloody Assizes,” perhaps from too great an emphasis on the executions on the heights and not enough on the trial itself and the deliberations that preceded it. From the War of 1812 until almost the present day Canadian political culture has shown little of the 18th-century whig concern with civil liberties. It is not, perhaps, unreasonable to discern in the wartime climate of opinion – the preoccupation with maintaining order and the demand by those in civil and military authority for immediate examples – an early manifestation of this tradition. Yet the wonder is that the result was not more bloody. In the end, young Robinson’s insistence upon adhering “as much as possible” to the “common course of Justice” avoided the gory consequences which surely would have attended the summary treatment of traitors by the military under martial law. But, as events turned out, there were victims and Jacob Overholser was surely one. Although spared the horror of 20 July 1814, he was convicted of an overt act of treason. Correct according to statutory definition, the charge of treason against him was lacking altogether in substance. Overholser was an enemy of Clark and the Angers but he bore no treasonous intent towards Upper Canada. The magistrates knew it, his neighbours knew it, and, indeed, Robinson admitted it. This knowledge, however, was sufficient only to respite Overholser’s execution, not to prevent his prosecution. The press of events – beleaguered authorities, a perilous military situation, and the perception of widespread disaffection and active treason – was his undoing.

AO, ms 4, especially J. B. Robinson letterbook, 1812–15; ms 74, package 27, Return of civilian prisoners confined in the Union Mill, 28 May 1814; Letter from T. Merritt, 18 July 1814; ms 500, Barbara Oberholser to Gilman Willson, bond, 9 Jan. 1818; MU 1368, Jacob Overholser; RG 4, A-I, 1; RG 22, ser.134, 4: 153–71. MTL, William Dummer Powell papers, L16, Calendar of prisoners at Ancaster, 1814: 12. Niagara South Land Registry Office (Welland, Ont.), Abstract index to deeds, Bertie Township: 210–11 (mfm. at AO, GS 2794); Deeds, Bertie Township, vol.A: 233–35 (mfm. at AO, GS 2796). Norfolk Land Registry Office (Simcoe, Ont.), Abstract index to deeds, Townsend Township, vol.A: 339. PAC, MG 11, [CO 42] Q, 318-1: 22–23, 30–31, 99–100, 124–27, 132–33, 142–43; 321: 59–68; RG 5, A1: 6514–15, 6523–24, 6528–35, 6667–73, 6704–9, 6741–43, 6761–69, 6779–81, 6787–91, 6804, 6845–52, 6859–64, 6868–75, 6880, 6902–4, 6932–33, 6937, 6939–41, 6943, 7307, 8258–61, 8511–12, 9345–46, 10200–1, 10221–23, 10340–41; RG 8, I (C ser.), 166: 84–87; 679: 148–50; 688C: 84–86a, 87–90, 97, 100–1; RG 9, I, B1, 2, Proclamation, 25 July 1814. Private arch., Christopher Robinson (Ottawa), Robinson papers (mfm. at AO). William Blackstone, Commentaries on the laws of England (4v., Oxford, 1765–69; repr. Chicago and London, 1979), 1: 357–61; 4: 74–93. U.C., House of Assembly, Journal, 1830, app., “Proceedings of the commissioners of forfeited estates,” 143–60. Kingston Gazette, 5 Aug. 1814. Montreal Herald, 6 Aug. 1814. E. A. Cruikshank, “John Beverley Robinson and the trials for treason in 1814,” OH, 25 (1929): 191–219; “A study of disaffection in Upper Canada in 1812–15,” RSC Trans., 3rd ser., 6 (1912), sect.ii: 11–65. W. R. Riddell, “The Ancaster ‘Bloody Assize’ of 1814,” OH, 20 (1923): 107–25. W. M. Weekes, “The War of 1812: civil authority and martial law in Upper Canada,” OH, 48 (1956): 147–61.

Cite This Article

Robert Lochiel Fraser III, “OVERHOLSER (Oberholser), JACOB,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 5, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed December 12, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/overholser_jacob_5E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/overholser_jacob_5E.html |

| Author of Article: | Robert Lochiel Fraser III |

| Title of Article: | OVERHOLSER (Oberholser), JACOB |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 5 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1983 |

| Year of revision: | 1983 |

| Access Date: | December 12, 2025 |