Source: Link

MARKLE (Marakle, Marcle), ABRAHAM, businessman, politician, and army officer; b. 26 Oct. 1770 in Ulster County, N.Y.; m. Mrs Vrooman, a widow, and they had at least one son; m. secondly Catharine —, and they had seven sons and two daughters; d. 26 March 1826 at his residence near Terre Haute, Ind.

Abraham Markle was of Dutch ancestry. By his own account he had four older brothers who served with John Butler*’s rangers and settled in the Niagara peninsula after the American revolution. That tie may explain Markle’s brief residence in Newark (Niagara-on-the-Lake) in 1794; if so, it was not sufficiently strong to keep him there, and through the remainder of the decade and into the next he lived at various places in New York State. In 1801 he ran a hotel in Niagara (Niagara-on-the-Lake) in partnership with one of Robert Hamilton*’s sons; they also operated a local stage line for a short period. On 25 Jan. 1802 the partnership was dissolved with Markle taking control for several months before selling the operation to his former associate. By 1806 he was established in Ancaster as a distiller. In the first quarter of that year his distillery had the largest production in the Niagara District, outstripping even Richard Hatt*’s large complex, Dundas Mills.

Markle possessed a considerable measure of entrepreneurial flair, particularly for making deals. He headed the 15 shareholders of the Union Mill Company, which in 1809 purchased the milling complex of John Baptist Rousseaux* St John, and there is a possibility that the group had been running it as early as 1806. Like most businessmen of the period, Markle was an active speculator in land. He did not operate on the scale of investors such as Robert Addison, but his lots were always well chosen for their marketability. In 1808 he patented, and then sold, 200 acres in nearby Nelson Township; the following year he purchased 200 acres in Aldborough Township. By 1810 he had acquired 700 acres in Ancaster Township, 200 acres in Markham Township, and 400 acres in Nelson which he leased from the crown. His portfolio was completed by the acquisition of a tavern licence in January 1813. As a businessman, if the records of the civil court are an indication, he managed to avoid the pitfalls which ruined Benajah Mallory* who, like Markle, would desert to the United States during the War of 1812. The court records reveal only one large judgement against Markle (for £200 in November 1806); his name does not appear again until February 1812 and then for a much smaller amount.

Markle’s election to the House of Assembly for Saltfleet, Ancaster, and the west riding of York in June 1812 thrust him to the centre of provincial concerns. President Isaac Brock* had high hopes that this parliament would overcome the opposition led by Joseph Willcocks* and pass the emergency legislation he deemed crucial to wartime survival. Until this point, the only hint, and it is a veiled one at best, of Markle’s political predisposition had been his refusal, reported in June 1811, to perform militia duty with the 5th Lincoln. The journals of the summer session of 1812 are no longer extant but the Niagara merchant William Hamilton Merritt* described Markle as one of Willcocks’s “adherents.” Three days after parliament met, Brock lamented a situation “critical, not from anything the enemy can do, but from the disposition of the people.” Apparently led by Willcocks and Markle, the assembly spent, in Brock’s words, eight days “in carrying a single measure of party – the repeal of the School Bill” – and in passing an act requiring public disclosure of treasonable practices before magistrates could commit suspects without bail. On the council’s recommendation, Brock prorogued parliament. Lack of hard evidence precludes anything more than conjecture as to Markle’s motives. There was nothing startlingly new about the presence of the opposition or its concerns; resistance to the executive arm of government had focused increasingly in the assembly, albeit with some interruptions, for a decade. Moreover, the Head of the Lake (the vicinity of present-day Hamilton Harbour) had already acquired a reputation for radicalism by the election of John Willson* in 1809. Markle obviously shared the broad concerns of the whig tradition, especially hostility to martial law and infringement of habeas corpus.

The opposition’s behaviour in the second session (25 February to 13 March 1813) is somewhat mystifying. Merritt observed that Willcocks and “his party” had become loyal. Moreover, Brock’s successor, Sir Roger Hale Sheaffe*, was so satisfied by the session that on 19 March he pronounced the death of the “cabal” within the house. The legislation passed was not especially controversial, and so perhaps there was less need for opposition. Besides, the military situation, after the victories at Detroit and Queenston Heights, was less desperate than the one faced by Brock. However, in 1814 President Gordon Drummond* drew attention to the “malignant influence” of Willcocks and Markle in rejecting Sheaffe’s call for a “suitable modification of the habeas corpus Act.” Since the journals for this session are also missing, events in the house must remain obscure.

In the course of 1813, the climate of opinion with respect to the maintenance of civil law during wartime had begun to change. Nothing was more jarring than the actions of the disaffected such as Elijah Bentley* during the occupation of York (Toronto) in April 1813 and the Americans’ subsequent push up the peninsula. In the aftermath, faith in due process faltered and collapsed: on 8 May “men of some standing and weight in this Society and holding real property to a great extent,” men such as Thomas Dickson and Robert Nichol, emphasized to Brigadier-General John Vincent* that “self-defence” had become paramount; “recourse only to the civil laws . . . would be unavailing and . . . endanger our existence as a people and government.” When on 6 June the British re-established their military presence with victory at Stoney Creek, fearful loyal subjects seized the opportunity to act against suspected traitors. A mere five days later Markle was ordered to appear before Vincent. Informed that “there were many Complaints lodged Against Me,” Markle was sent to Kingston for detention on 17 June.

“Innocent & Unhappy,” Markle immediately petitioned for release, proclaiming that it had been “Herriditary from My fore fathers to the Present age to be friends to the British Government.” The charges against him he dismissed as “groundless,” the fabrications of “My private Enemies.” “Had I not suffered Myself to be Elected,” Markle averred, “I should Never have been called disloyal or a traitor.” Fearful for the safety of his family, “exposed to indians Who are Daily destroying the property of Our Neighbours,” he was released. Some sources claim that Markle made his way back to Ancaster, but a militia return dated 22 June of those who had gone to the United States includes Markle. Yet late in November Merritt reported that Markle had “passed by the morning before, to join the enemy.” What is certain is that by 12 Dec. 1813 he was a captain in the Company of Canadian Volunteers, formed by Willcocks after he had left for the United States. His enlistment was a coup for Willcocks, who described him as an assemblyman “possessing a Large property, and a very powerful influence.”

The volunteers, dedicated to establishing a republic in British North America, fought mainly as guerrillas or scouts. Knowledge of the local territory and contacts among the population gave them an edge at this type of warfare. Moreover, they were eager to settle old scores and sought out unprotected civilian targets. The unit saw action during the burning of Niagara in December 1813 and later at the British raids on Fort Schlosser (Niagara Falls), N.Y., and Lewiston. Markle was wounded “severely” during one of the latter engagements, but he recovered sufficiently to accompany a large American force which landed in Upper Canada at Dover (Port Dover) on 14 May 1814 and burned every building between the village and Turkey Point, including Robert Nichol’s mills. Commissioned major on 19 April, Markle acted as liaison with Indians in New York before being stationed at Fort Erie until 31 August, when he moved to Albany. On 15 November Markle and another officer charged Benajah Mallory, Willcocks’s successor as commander of the volunteers, with embezzlement and felonious conduct. Mallory was suspended and Markle assumed command of the unit. The following day he received permission to move his family “Estward . . . to procure a situation to settle them.” When his unit was disbanded in March 1815, he seems to have been living at Batavia.

Markle’s treason ranks on a scale with that of Willcocks and Mallory. Unfortunately, the lack of sources makes it difficult to judge the reason for his conduct. American historians tend to repeat the conclusions of the family historian that Markle, aided by his “Masonic connections,” had fled official persecution in the courts and elsewhere, persecution that had resulted from his remarks “favorable to the annexation of Canada” by the United States. However, court minute-books do not reveal one single instance of official persecution of Markle. The only documented case of harassment, and it was not of an official nature, was his brief incarceration in June 1813. Mallory accused Markle of opportunism, suggesting that he “never Left Canada from Principle but from a narrow Escape from his Creditors.” That may be, but there is no evidence either in court or forfeited-estate records to substantiate the allegation.

Unlike Ebenezer Allan*, Markle had remained loyal at the outbreak of war. It is possible that with so much to lose he wanted to await an outcome favourable to his interests. But in that case neutrality and not opposition would have been the prudent course in 1813. Crucial to an understanding of his treason, therefore, is its timing. Markle’s successor in the assembly, James Durand, decried the summer of 1813 as a period of military despotism. An echo of this view is found in an American newspaper’s obituary for Markle. Opposing “the corruption and oppression practised upon the people,” Markle, it said, “gave strong evidence that the spirits of those who had laid the basis of American Freedom, were very similar to his own.” As for his treason, it was suggested that when the “civil law had been prostrated by martial despotism, the outrage and violence of the public functionaries toward him proved that the laws no longer afforded him protection, and consequently he was absolved from any allegiance he could have owed that government.”

Unlike his brothers, Markle had been too young for active involvement in the loyalist cause during the American revolution. Moreover, prior to 1801 he had spent almost his entire life in the United States. His political sympathies, then, were likely to have been democratic. Certainly in Upper Canada he shared the most radical tendencies in the opposition, those of Willcocks. Events during the summer of 1813 forced Willcocks to the logical extension of his beliefs, republicanism. They had a similar effect on Markle and Mallory. Convinced that civil rights had been extinguished, these three men saw no alternative but to cross the border – desperate times required desperate measures. It is, perhaps, significant that Markle’s inn in Terre Haute, Ind., the Eagle and the Lion, carried a sign depicting a “sorely dejected British lion, fast losing its eyes under the attacks of a victorious eagle.”

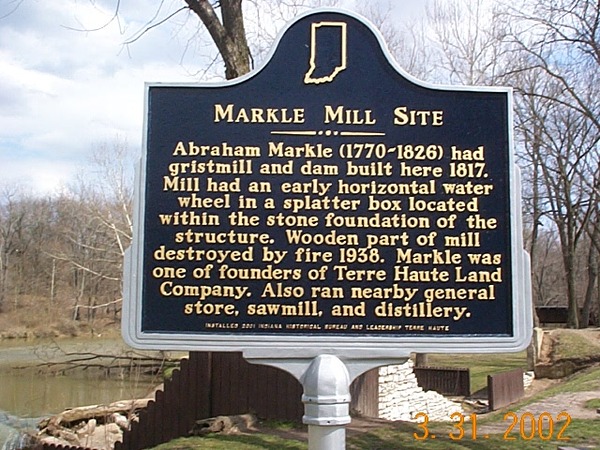

After the war Markle was alert to new opportunities for recouping his large personal losses. Indicted for treason on 24 May 1814 and convicted in absentia, in 1817 he was declared an outlaw and his lands vested in the crown. In December 1815 an acquaintance had estimated the value of his Upper Canadian holdings at $26,900. Small wonder that Markle participated in the lobbying of the American government which led in early 1816 to the passage of bounty legislation compensating volunteers. The bounty land acts of 1816 and 1817 entitled Markle to 800 acres in total. In June 1816 he applied for additional land in his own right and another 2,080 acres for others with himself as assignee; a month later he filed papers for 320 acres more. All these petitions were granted. He located his lands in Indiana’s Wabash valley and on 19 Sept. 1816 became one of the five shareholders of the Terre Haute Land Company. The town of Terre Haute soon became the district capital for the newly organized Vigo County; Markle leapt at the possibility for investment. He owned several mills, a distillery and tavern, and land. He mortgaged his land to finance further expansion but overextended himself and by 1823 he faced foreclosure. At his death he had extensive property investments, mills, and shipping and manufacturing interests, but he was heavily in debt.

Markle was not a popular figure in Indiana. He frequently resorted to the civil courts to secure payment of debts. He himself was hauled before the criminal courts: in one instance on gambling charges and in another for assault and battery. When he ran for the post of lieutenant governor on 5 Aug. 1822 he received a mere two votes. Local American historians depict him as a large man, of great energy, quick-tempered, but often generous and warm-hearted. He loved horse-racing and enjoyed drinking. He died as a result of an apparent stroke, incurred while pulling up fence posts on his farm. A member of the local masonic lodge, he was buried with its full honours. Vilified in Upper Canadian history as a traitor, when remembered at all, he is viewed by Americans as a soldier in freedom’s cause, a worthy inheritor of the revolutionary tradition.

AO, MU 1368; MU 2555, receipts, 13 April 1801, 6 Jan. 1810; RG 1, A-IV, 16: 4; C-IV, Nelson Township, concession 3, lots 5, 11; RG 22, ser.131, 2: ff.3, 6, 16-17. BL, Add.

Cite This Article

Robert Lochiel Fraser, “MARKLE (Marakle, Marcle), ABRAHAM,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 6, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed March 13, 2026, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/markle_abraham_6E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/markle_abraham_6E.html |

| Author of Article: | Robert Lochiel Fraser |

| Title of Article: | MARKLE (Marakle, Marcle), ABRAHAM |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 6 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1987 |

| Year of revision: | 1987 |

| Access Date: | March 13, 2026 |