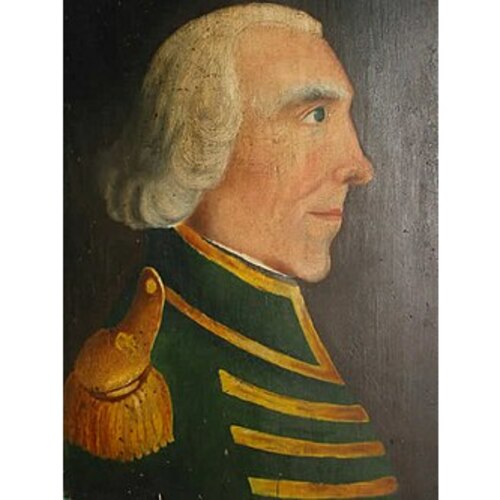

Source: Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

BUTLER, JOHN, army officer, office-holder, and Indian agent; baptized 28 April 1728 at New London, Connecticut, son of Walter Butler and Deborah Ely, née Dennison; m. Catalyntje Bradt (Catharine Bratt) about 1752, and they had four sons and one daughter who survived infancy; d. 13 May 1796 at Newark (Niagara-on-the-Lake, Ont.).

Virtually nothing is known of John Butler’s youth. It seems clear, though, that he began his association with the frontier and the Six Nations at an early age. His father, a captain in the British army, brought his family to the Mohawk valley of New York about 1742, and three years later John was at Oswego (Chouaguen) with him. Walter Butler was apparently on close terms with William Johnson and it is quite possible that John received some of his early training in dealing with the Indians from him. Certainly Johnson became impressed with Butler’s abilities in Indian languages and diplomacy. In May 1755 he brought him as an interpreter to the great council at Mount Johnson (near Amsterdam, N.Y.); the same year, when Johnson was given command of the colonial expedition against Fort Saint-Frédéric (near Crown Point, N.Y.), he appointed Butler a lieutenant over the Indians, a loosely defined position which involved some nominal leadership. Butler continued to serve in this capacity throughout the Seven Years’ War, reaching the rank of captain. He was with James Abercromby at the attack on Fort Carillon (Ticonderoga, N.Y.) and with John Bradstreet at the capture of Fort Frontenac (Kingston, Ont.) in 1758. The next year he was second in command of the Indians when Johnson took Fort Niagara (near Youngstown, N.Y.), and in 1760 he held the same post in Amherst’s force advancing on Montreal.

After the war Butler continued to work under Johnson in the Indian department, appearing as an interpreter at councils with the Indians during the 1760s. He settled his family at Butlersbury (near Johnstown, N.Y.), the estate his father had left him, and was appointed a justice of the peace. In the early 1770s he apparently retired from the Indian department to devote himself to his growing properties. When Tryon County was established in 1772 he was appointed a justice of the Court of Quarter Sessions and lieutenant-colonel of the militia regiment commanded by Guy Johnson. Sir William died in 1774 and Guy became Indian superintendent; Butler was again appointed an interpreter.

At the outbreak of the Revolutionary War in 1775 Butler, together with other Mohawk valley loyalists including his sons Thomas and Walter, and Guy Johnson, left to join the British forces in Canada. Butler’s wife and other children were interned by the rebels the following year and he did not see them again until an exchange was arranged in 1780. In Montreal, Johnson proposed to Governor Guy Carleton* that the Six Nations and the Indians of Canada be used to put down the rebellion in the “back settlements” of western New York and Pennsylvania. Carleton, however, refused to use them other than as scouts and in defence. Faced with this refusal, and aware of the arrival of Major John Campbell with a commission as agent for Indian affairs in Quebec, Johnson and Christian Daniel Claus decided to carry their case to Britain and left in November 1775. Butler remained as acting superintendent of the Six Nations and, with American forces threatening Canada, was sent to Fort Niagara. His instructions were to do all he could to keep the Six Nations out of the fighting but loyal to Britain, since the British considered the Iroquois to be allies. Although the inclination of the Indians, particularly those who were under the influence of Samuel Kirkland, a New Light missionary from Connecticut, was to sign pacts of neutrality with the rebels, Butler had considerable success in maintaining their alliance with Britain. During the following year and a half he established a network of agents among the tribes from the Mohawk River to the Mississippi, which became a valuable source of intelligence for the British and an aid to loyalists fleeing to Canada. In the early summer of 1776 Butler also raised and dispatched a party of loyalists and Indians to aid in the expulsion of the American forces from Canada.

In 1777 the British government decided that its Indian allies should be used offensively against the rebels, and in May Butler was ordered to collect as large a force as possible from among the Six Nations and to join Lieutenant-Colonel Barrimore Matthew St Leger’s expedition at Oswego for an attack against Fort Stanwix (Rome, N.Y.). Although Butler had only a month to accomplish this task, he succeeded in persuading 350 Indians, mostly Senecas, to accompany the expedition. By this time he had received a regular appointment as deputy superintendent of the Six Nations from Guy Johnson, who had arrived in New York in 1776. Nevertheless, at the beginning of the expedition Claus arrived with a commission as superintendent of all Indians employed on it. Butler was intensely disappointed at this supersession, but there is no indication that it affected his conduct towards Claus. Butler was present at the victory of Oriskany, near Fort Stanwix, on 6 Aug. 1777, where the Indians and some unorganized loyalist rangers bore the brunt of the fighting and casualties [see Kaieñˀkwaahtoñ].

At the end of the St Leger expedition Butler travelled to Quebec. In September Carleton commissioned him to raise a corps of provincial rangers from among frontier loyalists who had fled to Fort Niagara. Promoted major commandant, Butler was assigned Niagara as his permanent base. His first orders called for him to join Burgoyne’s expedition, but it ended in disaster before he had even begun to recruit.

The following year, with recruiting now well under way, Butler’s Rangers and a force of Indians led by Kaieñˀkwaahtoñ and Kaiũtwahˀkũ (Cornplanter) undertook their first expedition against the American frontier settlements, the extraordinarily successful raid of 3–4 July on the Wyoming valley, Pennsylvania. Ill health forced Butler to spend the rest of 1778 at Niagara but in November his son Walter led the well-known raid against Cherry Valley (N.Y.). The enormous effect of these and other raids that year and early the next may be gauged by the fact that Congress was forced by public pressure in 1779 to divert to the frontier an army of several thousand men, many of them regulars, under Major-General John Sullivan. Its objectives were to destroy the settlements and lands of the Six Nations allied to the British and to capture as many prisoners as possible. The American campaign did indeed throw the British and Indians on the defensive and Butler, with a force of several hundred men, was defeated at Newtown (near Elmira, N.Y.) on 29 August. The Americans then devastated the Indian villages of the Finger Lakes region. Thousands of Indians were forced to turn to the British for subsistence, but the base at Niagara remained and in 1780 the rangers and Indians were back at their work. In the following years Butler’s Rangers extended their operations. A company was assigned to the posts at Oswegatchie (Ogdensburg, N.Y.) and Detroit, and from all bases rangers and Indians carried out almost continuous harassing operations against the whole frontier from the Hudson River to Kentucky.

The Butlers and the war they waged have been condemned by generations of American historians as “treacherous,” “barbarous,” and “diabolically wicked and cruel.” But there is little basis in fact for these charges. Frontier warfare was always cruel, and there is no evidence that the Butlers made it more so and some to support the contention of a few historians that they acted with all the humanity the situation would allow. Condemnations have usually been based on the assumption that the Butlers’ raids were motivated by hate and by a desire for revenge. The operations of the rangers, however, had the important objectives of denying supplies to the Continental Army and of drawing off as many American troops as possible from seaboard operations. That these aims were achieved is indicated in part by the Sullivan campaign and also by the fact that Tryon County’s prewar population of approximately 10,000 had been reduced, by an exodus away from the threatened area, to 3,500 by 1783.

Butler’s interests during the revolution were not exclusively military. As early as 1776, by using his influence as deputy superintendent over the Indian trade, he managed to monopolize the trade with the loyalists at Fort Niagara as well as the lucrative Indian department trade for himself and Richard Pollard*, a merchant at the fort, and later for Thomas Robinson, Pollard’s successor. This monopoly was, however, broken in 1779 when Guy Johnson assumed control of Six Nations affairs and was replaced by one operating in Johnson’s interest.

Butler was closely involved in the first settlement on the Canadian side of the Niagara River. Early in the war he sited the ranger barracks opposite the fort. In 1779, when Governor Haldimand* decided to encourage agriculture in the neighbourhood of the fort as a means of reducing the garrison’s dependence on supplies from Montreal, he assigned Butler the task of finding appropriate people from among the loyalist refugees. Butler found in this responsibility an opportunity both to impress Haldimand with his competence and to establish himself as leader and source of patronage for the Niagara loyalists. By the end of the war he had settled a number of families opposite the fort, and some of his favourites on the best lots. Indeed, the first name of the new settlement was Butlersbury. When Butler’s Rangers was disbanded in June 1784, Butler and his family and a large part of his corps settled there. From this settlement grew the town of Newark, and Butler remained one of the town’s most prominent citizens until his death.

The end of the revolution had also brought Butler ill fortune. His property in New York had been confiscated in 1779, and, although he received half pay as a lieutenant-colonel and a 500-acre land grant, the loyalist claims commission refused to recognize many of his claims to Indian lands. In addition, the money he made during the war was lost, apparently in a speculation in Indian goods. In an attempt to reverse this trend, he travelled to Quebec and England in 1784 and 1785 but was unsuccessful in obtaining for his sons the concession giving exclusive use of the Niagara portage route and for himself the higher salary he desired.

Butler also played a prominent part in the local affairs of the Niagara region. He was appointed a justice of the Court of Common Pleas and a member of the district land board when the District of Nassau was established in 1788, and he also became lieutenant-colonel of the Nassau militia, and, at a later date, colonel of the Lincoln County militia. Sir John Johnson* was, however, able to use his influence to prevent Butler or any of his rangers from receiving important offices when the province of Upper Canada was formed in 1792. Similarly, Butler did not rise further in the Indian department. He tried to recoup his family’s fortunes through an illegal attempt to supply trade goods to the Indian department involving his son Andrew, his nephew Walter Butler Sheehan, and Samuel Street*, a Niagara merchant. Butler also used his prestige as an Indian superintendent to cooperate with some Americans in a speculation involving Iroquois lands in New York state. When both these ventures failed, Butler turned to farming, milling, and land speculation, but he had only mediocre success.

As deputy superintendent of the Six Nations, Butler played a large part in the purchase of much of southwestern Ontario, including the Grand River lands, from the Mississaugas [see Wabakinine]. He had a significant role in the diplomatic and military manœuvring with the Americans and Indians in the years before the evacuation of the border posts in 1796. In 1792 the American government sought to arrange a treaty with the Indians of the old northwest. Butler attended the unsuccessful conference at Lower Sandusky (Ohio) the following year, and with Joseph Brant [Thayendanegea*] and the Six Nations opposed the intransigent position taken by the western Indians and Alexander Mckee that the boundary between American and Indian territory be no farther west than the Ohio River. It was to be Butler’s last significant public service. During the conference his health failed and he never fully regained it. Although he remained a valuable adviser to the government of Upper Canada, by late 1795 Lieutenant Governor Simcoe* regretfully considered removing him from his Indian department position because of his growing infirmities.

John Butler was one of the great figures in European-Indian relations in North America. His influence with the Indians was clearly based upon their trust of him. The success he had in keeping most of the Six Nations out of the fighting but attached to the British cause during the first two years of the revolution speaks to his influence, as does the fact that to him fell most of the burden of explaining to the Indians the British concession of the western lands in 1783. The greatest tribute probably came from Joseph Brant, who said at an Indian funeral ceremony for Butler that he “was the last that remained of those that acted with that great man the late Sir William Johnson, whose steps he followed and our Loss is the greater, as there are none remaining who understand our manners and customs as well as he did.”

Butler’s relations with the Johnson clan have been the subject of some speculation. He was part of the group closest to Sir William in the 1760s, and the suggestion has been made that when he apparently left his position in the Indian department about 1771 it was because of a falling out with Sir William. The more probable reason for his departure was Sir William’s decision to give the limited number of deputy appointments in the department to relatives, such as Claus and Guy Johnson, his sons-in-law, and John Dease, his nephew. Butler, seeing little opportunity for his own advancement, probably chose to devote himself to the development of his estate. There is no evidence, however, of animosity in the break. When Johnson drew up his will in early 1774 he named Butler as one of his executors and a guardian of his children by Mary Brant [Koñwatsiˀtsiaiéñni]. Nor would Butler have received his various civil and military appointments in Tryon County without Johnson’s approval. Indeed Butler, who later selected two of his own sons to be officers in the first company of his rangers, probably understood Johnson’s motives completely.

The difficulties with the Johnson group appear to have been instead with Guy and Claus in Canada. Their departure for Britain in late 1775 in the face of the American invasion was considered by Carleton to be akin to desertion. This action, and Butler’s obvious competence in dealing with the Indians, put him in great favour with both Carleton and Haldimand. Once Johnson and Claus returned to Canada they saw Butler as a threat to their positions and sought to undermine his reputation, but they were ultimately unsuccessful. Carleton retained him as agent at Niagara and commissioned him to raise the rangers despite Claus’ derogatory letters, and Haldimand, not by chance, promoted him lieutenant-colonel in 1779, just when Guy Johnson arrived back in Canada. A short time later Haldimand intervened to prevent Johnson from removing Butler as agent at Niagara. Carleton’s and Haldimand’s support of Butler, however, was not merely a function of their dislike of Claus and Johnson. Both governors were clearly convinced that Butler was the most competent man for the job and probably appreciated his loyalty and deep sense of duty; Carleton later described him as “very modest and shy.”

The only known picture of John Butler is a small profile print held by the PAC; Charles William Jefferys* based a portrait on this print. There is a memorial to Butler in St Mark’s Church, Niagara-on-the-Lake, Ont.

BL, Add. mss 21670, 21699, 21756, 21765–70, 21775, 21873. Metropolitan Toronto Library, U.C., Court of Common Pleas, Nassau District, minutes, 12 Jan. 1792. PAC, MG 11, [CO 42], Q, 13; 14, pp.157–58; 15, pp.225–27; 16–1, pp.91–98; 17–1; 26; 50; MG 24, D4; MG 29, E74; MG 30, E66, 22; RG 1, L3, 1, no.87; 2, nos.40, 99. PAO, Canniff (William) papers, package 13, Goring family; Reive (W.G.) coll.; Street (Samuel) papers, cancellation of articles of agreement between Andrew Butler and Samuel Street, 4 Jan. 1797; RG 1, A-I-1, 2. PRO, AO 12, bundle 117; 13/21; 13/89; 13/90; 13/109; CO 42/26, p.66; 42/36–40; 42/42, pp.144–47; 42/43, pp.786–89; 42/46, pp.395ff., 411–18, 431, 458ff., 479ff., 491ff.; 42/49; 42/50, pp.121–22; 42/55, pp.105–8; 42/69, p.245; 42/73 (PAC transcripts); 323/14; 323/15; 323/23; 323/30; WO 28/4; 28/10. Correspondence of Lieut. Governor Simcoe (Cruikshank), I, 246, 256, 324, 365–66, 373–74; II, 113, 155, 267; III, 278–79, 323; IV, 101, 125, 217, 264–65. Johnson papers (Sullivan et al.), I, 13, 27–29, 108, 380, 516, 625. NYCD (O’Callaghan and Fernow), VII; VIII, 304, 362–64, 497–500, 688–89, 718–23, 725–27. PAC Report, 1884–89. “The probated wills of men prominent in the public affairs of early Upper Canada,” ed. A. F. Hunter, OH, XXIII (1926), 328–59. “Records of Niagara, 1784–9,” ed. E. A. Cruikshank, Niagara Hist. Soc., [Pub.] (Niagara-on the-Lake), 40 (n.d.), 24–27. DAB. R. W. Bingham, The cradle of the Queen City: a history of Buffalo to the incorporation of the city (Buffalo, N.Y., 1931), 72–73. E. [A.] Cruikshank, The story of Butler’s Rangers and the settlement of Niagara (Welland, Ont., 1893), 11–12, 23–25, 27–28, 33–37, 39–51, 59, 63–75, 79–88, 91–98. Howard Swiggett, War out of Niagara: Walter Butler and the Tory rangers (New York, 1933; repr. Port Washington, N.Y., 1963), 5, 7–13, 126–32, 169–201, 225–70, 286. P. H. Bryce, “Sir John Johnson, baronet: superintendent-general of Indian affairs, 1743–1830,” N.Y. State Hist. Assoc., Proc. (New York), XXVI (1928), 233–71. E. [A.] Cruikshank, “The King’s Royal Regiment of New York,” OH, XXVII (1931), 193–323; “Ten years of the colony of Niagara, 1780–1790,” Niagara Hist. Soc., [Pub.], 17 (1908), 2–10, 16–17, 24–31, apps.A, B. Reginald Horsman, “The British Indian department and the abortive treaty of Lower Sandusky, 1793,” Ohio Hist. Quarterly (Columbus), 70 (1961), 189–213. W. H. Siebert, “The loyalists and the Six Nation Indians in the Niagara peninsula,” RSC Trans., 3rd set., IX (1915), sect.ii, 79–128.

Cite This Article

R. Arthur Bowler and Bruce G. Wilson, “BUTLER, JOHN (d. 1796),” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 4, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed January 1, 2026, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/butler_john_1796_4E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/butler_john_1796_4E.html |

| Author of Article: | R. Arthur Bowler and Bruce G. Wilson |

| Title of Article: | BUTLER, JOHN (d. 1796) |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 4 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1979 |

| Year of revision: | 1979 |

| Access Date: | January 1, 2026 |