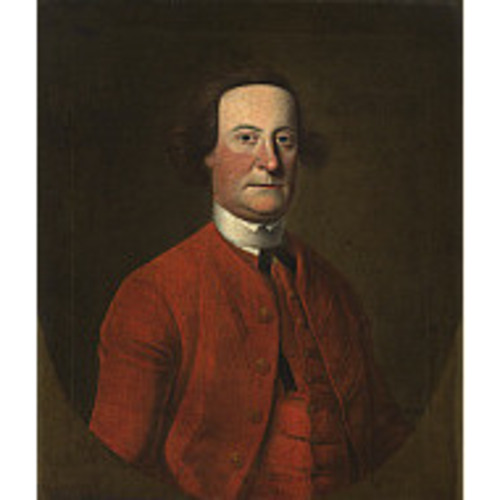

Source: Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

BRADSTREET, JOHN (baptized Jean-Baptiste), army officer and office-holder; b. 21 Dec. 1714 at Annapolis Royal, Nova Scotia, second son of Edward Bradstreet and Agathe de Saint-Étienne* de La Tour; m. Mary Aldridge, and they had two daughters; d. 25 Sept. 1774 in New York City.

John Bradstreet and his brother Simon served in Nova Scotia as volunteers in Richard Philipps*’ regiment (40th Foot) until 1735, when their mother, working through the regimental agent King Gould, secured commissions for them. John received an ensign’s rank and thus began a military career which would be capped when he became a major-general in 1772.

Confusion surrounds the early years and family of John Bradstreet as the result of the presence in Nova Scotia of a cousin of the same name. After the latter’s death John compounded the confusion by marrying his widow, and two of the four children believed to be his were actually his cousin’s. In later years Bradstreet was reticent to discuss his family background and the Nova Scotian phase of his career. No doubt uneasiness about the effect his Acadian ancestry would have on his career in the British army, as well as his involvement in questionable trading activities, explain his silence. The result has been a historical picture of Bradstreet as an enigmatic figure who first emerged during the campaign against Louisbourg, Île Royale (Cape Breton Island) in 1745. As a young officer stationed at Canso in the 1730s, however, Bradstreet had been very active. In addition to carrying out his military duties, he had developed a lucrative trade in provisions and lumber with the French fortress. Despite advice from Gould to “Knock off” such activities lest they damage his military career, Bradstreet continued his mercantile connections with Louisbourg well into 1743. Not surprisingly, when Canso and its garrison were captured by the French in May 1744 [see François Du Pont Duvivier], Bradstreet was given preferred treatment. During the next few months he became the message bearer between the commandant of Louisbourg, Jean-Baptiste-Louis Le Prévost* Duquesnel, and Governor William Shirley of Massachusetts as prisoner exchanges were discussed. Bradstreet also worked at turning his knowledge of Louisbourg to good advantage in New England and improving his chances of promotion in Britain. The very day in September 1744 that the released Canso garrison reached Boston, Bradstreet and George Ryall, a fellow officer in the garrison, submitted a report on Louisbourg to Shirley which stressed the fortress’s importance to the French empire and hinted at its vulnerability. Three months later, Bradstreet presented Shirley with a plan for an assault on the French stronghold. Whether it was used as the basis for the 1745 attack is uncertain since no copy is now available. William Vaughan* claimed to have been the author of the definitive plan; however, Bradstreet was described by William Pepperrell* as “the first projector of the expedition,” and Shirley claimed that it was because of Bradstreet’s “Intelligence and advice . . . that I set the Expedition on ffoot.”

Although disappointed that he was not given command of the expedition, Bradstreet accepted a provincial commission as lieutenant-colonel of the 1st Massachusetts Regiment and contributed to the victory at Louisbourg. Pepperrell, Commodore Peter Warren*, and Shirley all applauded his performance. The day after the surrender Bradstreet was commissioned “Town Major of ye City and Fortress,” but the more substantial rewards he clearly expected were not forthcoming. Moreover, after Charles Knowles became governor of Cape Breton in June 1746, even his position as town major was lost. Personal animosity developed between the two men, and rewarding sidelines for Bradstreet, such as providing rum and fuel to the garrison, were curtailed by Knowles, who claimed that he no longer permitted Bradstreet “to Plunder the Government.” Although Bradstreet had been appointed captain in Pepperrell’s newly established regular regiment garrisoning the fortress and on 16 Sept. 1746 was appointed lieutenant governor of St John’s, Newfoundland, he remained bitter. Further attempts to improve his situation failing and continued frustration at Louisbourg being unacceptable, he journeyed to St John’s in August 1747 to begin active service as lieutenant governor.

Newfoundland turned out to be only a temporary resting place, however, since in the fall of 1751 he went to England. Armed with his journal of the siege, reciting his contributions, and bemoaning his treatment, he soon regained the support of King Gould and Gould’s son Charles which he had lost because of his trading activities, and he aroused the interest of powerful persons such as Sir Richard Lyttleton, an intimate of William Pitt, Charles Townshend, later chancellor of the exchequer under Pitt, and Lord Baltimore. Although both Townshend and Baltimore were ultimately unsuccessful in their attempts to obtain preferment for him, Lyttleton and Charles Gould were to prove more useful. Having gained badly needed “Easie Access” to patrons in England, Bradstreet returned to America in 1755 with Major-General Edward Braddock’s expedition.

Now a captain in Pepperrell’s newly raised 51st Foot, he was initially assigned to Shirley’s campaign against Fort Niagara (near Youngstown, N.Y.) the same year. Lacking experienced personnel, the Massachusetts governor relied heavily on his old Louisbourg adviser. In the spring of 1755 he ordered Bradstreet to Oswego (Chouaguen) to improve its defences and prepare it as a base for the assault on Niagara. Bradstreet carried out his orders energetically and in August he was promoted brevet-major and adjutant-general. During the summer, however, Shirley had encountered difficulty in organizing and transporting his army to Oswego, and as the opportunity for a Niagara strike slipped away Bradstreet sought permission for an immediate attack on the French fort. Shirley had rejected this plan, and in September he abandoned the campaign altogether. He decided that an attack on Fort Frontenac (Kingston, Ont.), which he described as “the Key” to Lake Ontario, must be the first campaign of 1756, and he assigned the task to Bradstreet.

One of Bradstreet’s first duties in the spring was to lead a convoy of bateaux to reinforce the garrison at Oswego. Once there he was to select the necessary men and supplies and attack Fort Frontenac. He had difficulty in reaching Oswego, however, and its weakened garrison and incomplete fortifications made it obvious that an offensive against Frontenac was impossible. Since French pressure on Oswego was now growing, Bradstreet directed his efforts to keeping the supply line between Oswego and Albany open. He returned to Oswego once more on 1 July 1756 and then waited impatiently in Albany to set out again. In mid August, however, Montcalm* captured Oswego.

By then Lord Loudoun had replaced Shirley as commander of the British forces in America. Shirley’s enemies, such as Sir Charles Hardy and Sir William Johnson, identified Bradstreet as one of his cohorts, but Bradstreet was quick to dissociate himself from his former commander. Forewarned in March 1756 by Charles Gould that Shirley “is no longer in great esteem here,” Bradstreet became somewhat uncooperative when Shirley attempted to collect information for his own vindication. He moved instead to endear himself to Loudoun and his staff, and his strategy worked perfectly. Of all the measures that Shirley had authorized, only Bradstreet’s performance “won the unqualified praise of Shirley’s successors.” With Loudoun’s approval the bills for his bateau service were honoured, he received a captaincy in the Royal Americans (60th Foot) when the 51st was disbanded early in 1757, and he became virtual quartermaster and aide-de-camp to Loudoun. During the spring of 1757 he assembled supplies and transports at Boston for Loudoun’s expedition against Louisbourg, and at Halifax in August he was among those who felt that the attack should not be postponed.

Although disappointed by the cancellation of the expedition, Bradstreet was encouraged to learn that William Pitt had become the British prime minister, and he wrote to Lyttleton seeking “a favourable mention.” He was quite willing to specify appointments to which he considered himself entitled, such as the governorship of New Jersey, the colonelcy of a regiment of rangers, or the post of quartermaster general. Moreover, once again offering schemes to his superiors, early in September 1757 he sent Lyttleton his thoughts on how Canada could be conquered. For complete victory in North America a three-pronged assault should be launched against the French possessions. One army should reduce Louisbourg and then proceed against Quebec while another should move from Albany to capture forts Carillon (Ticonderoga, N.Y.) and Saint-Frédéric (near Crown Point, N.Y.) and then link up with the third army, which was to attack across Lake Ontario from Oswego. The combined forces should then proceed “in a short time [with] the reduction of the Town of Montreal.” Bradstreet thus offered a strategy which bears a striking resemblance to the basic plan that Pitt used to achieve the conquest of Canada in the campaigns of 1758 to 1760.

“Charmed with the Spirit and Enterprising Genius” of Bradstreet, Lyttleton passed his ideas along to Pitt and Lord Ligonier, commander-in-chief of the British army. The latter was definitely influenced by them in drawing up his plans for the 1758 campaign. Quick action followed Bradstreet’s request for promotion; on 1 Jan. 1758 Lyttleton reported to Charles Gould with obvious satisfaction that “I have Obtained for our Friend Bradstreet the rank of Lt. Col in the Kings Service, as Deputy Quarter Master General for America.”

While he was winning promotion in England, Bradstreet was being assigned increasingly important tasks in America. Loudoun ordered him to oversee the construction of bateaux in the Albany region for service on Lake Ontario and the Hudson and St Lawrence rivers in the coming campaign, and he also approved Bradstreet’s proposal for an attack on Fort Frontenac in the early spring. These plans were abruptly altered early in March, however, when Loudoun was replaced by James Abercromby. In Pitt’s orders to Abercromby, Bradstreet was assigned to quartermaster’s duties in the southern colonies. Abercromby was aware of Bradstreet’s talents, however, and in “an inspired piece of disobedience” decided to use him in his campaign against Fort Carillon. Accordingly, Bradstreet supervised the construction of bateaux and the movement of men and provisions up the Hudson River in preparation for the attack. When Viscount Howe (George Augustus Howe), Abercromby’s second in command, was killed, Bradstreet “took up the slack” since Thomas Gage, now second in command, failed to emerge as a key adviser to Abercromby. With Abercromby’s permission he took a force of several thousand regulars and provincials on a more direct route to Carillon than the army had been following. Once before the fort with this advance guard, Bradstreet requested permission to launch an immediate attack. Abercromby did not take “the least Notice” of this request but instead came up with the rest of the army and ordered the attack for the next day. The delay proved costly: on 8 July the strengthened French forces and entrenchments hurled back successive waves of British attackers. Following Abercromby’s decision to withdraw, Bradstreet took command at the landing place and converted a near disastrous rush for the boats into an orderly embarkation.

While others licked their wounds in the aftermath of the British defeat, Bradstreet resurrected his proposal for an attack on Fort Frontenac and secured Abercromby’s approval. His largely colonial force of approximately 3,000 reached Lake Ontario on 21 August and four days later was within sight of the French fort. Frontenac was in no condition to resist a siege and the fort’s commander, Pierre-Jacques Payen de Noyan et de Chavoy, surrendered on the 27th. After plundering, burning, and demolishing the fort, Bradstreet’s force retreated to British territory. With this one brilliant stroke the lifeline of the French Great Lakes empire had been severed. More directly, the capture of French provisions at the post, the destruction of the French naval flotilla on Lake Ontario, and the resultant blow to French prestige among the Indians all contributed to the final defeat of New France.

Bradstreet’s triumph was applauded in Great Britain, and he was promptly promoted colonel in America, the promotion being backdated to 20 August. But ironically, although his military career had risen to its apex during Britain’s years of defeat, his feelings of frustration and neglect intensified as the victorious years of the British war effort began. Under his new commander, Jeffery Amherst, Bradstreet served as deputy quartermaster general at Albany, winning Amherst’s consistent respect for the conscientious performance of his duties. During the preparations for the 1760 campaign Bradstreet’s ceaseless diligence caused his health to collapse and brought him to death’s door. As Amherst’s army embarked upon the final reduction of Canada, Bradstreet remained behind at Oswego, confined to his bed. Although his quartermaster’s duties were financially rewarding and indeed increased his political and economic importance in the Albany region, as the war drew to a close he became increasingly concerned at what he considered the British government’s failure to reward adequately his contributions to the victory. His cause was not helped by Lyttleton’s departure from England in 1760 nor by Pitt’s fall from power in 1761, but the faithful Charles Gould continued to solicit on his behalf and in October 1763 secured his appointment as lieutenant governor of either Montreal or Trois-Rivières once Ralph Burton*’s choice was known. By this time Pontiac*’s uprising had broken out, and Amherst offered Bradstreet command of an expedition to the Great Lakes against the Indians. Reasoning that the successful completion of this task would carry more weight with the British government than his service in Canada, he accepted.

The operations planned for 1764 were directed primarily against the Delawares and the Shawnees; Bradstreet was to command a northern force moving from Niagara to Detroit, while Henry Bouquet was to command a southern force moving from Fort Pitt (Pittsburgh, Pa) towards the Muskingum River (Ohio). Unable for various reasons to leave Niagara until early August, and bitterly disappointed at the limited size of his force, Bradstreet convinced himself that his mission was also one of peacemaking. Thus he offered tentative peace terms to an Indian delegation which met him near Fort Presque Isle (Erie, Pa) on 12 August and conducted further negotiations after his arrival at Detroit on 27 August.

By mid September Bradstreet had reached Sandusky (Ohio) on his return journey. Gage, who had succeeded Amherst as commander-in-chief, had by now been informed of Bradstreet’s peacemaking activities and disavowed them, ordering Bradstreet to launch an overland attack against the Delawares and Shawnees. Bradstreet felt his weakened force was incapable of such a mission and remained at Sandusky until mid October, offering only a potential threat to the Indians and an indirect aid to Bouquet. The journey from Sandusky disintegrated into a nightmarish rout because of storms and lack of supplies, and it was not until 4 November that the remnants of the expedition began to arrive at Niagara. To his credit, Bradstreet had relieved Detroit, helped reopen the various posts on the Upper Lakes, and proved at least an indirect help to Bouquet’s more successful campaign. But to Gage and Sir William Johnson, Bradstreet had mismanaged the campaign and exceeded his instructions, and he emerged from the Detroit campaign with his military record and reputation badly tarnished.

After the Detroit disappointment Bradstreet continued to serve as acting deputy quartermaster general at Albany, a virtual sinecure since his departmental expenditures and responsibilities were cut to the bone by Gage. The unsympathetic Gage remained as commander-in-chief for the remainder of Bradstreet’s life, often thwarting his efforts at advancement. Bradstreet prospered financially through land speculation and other dealings, but his military career stagnated. Pet projects such as the establishment of a full-fledged colony at Detroit with himself as governor were still offered to the home authorities, but although the projects were at times carried to the brink of achievement they were ultimately unsuccessful. Equally futile were his requests for the governorships of Massachusetts, New York, or even Canada when he heard that Guy Carleton* contemplated “never returning” in 1770. In 1773 the possibility of his succeeding Gage was still being pursued, and his proposal for a Detroit colony was resubmitted the following year, only to be precluded by the Quebec Act. The old warrior was spared the news of this final rejection, as well as the spectacle of the open revolution he had long expected, since he died at New York City on 25 Sept. 1774. The next day, accompanied by an elaborate funeral cortège, Bradstreet’s body was borne to its final resting place in Trinity Church.

For an Anglo-American-Acadian a successful career in the mid-18th-century British army was not an easy undertaking. Nevertheless, Bradstreet was able to combine a prominent role in military triumphs with proper timing, well-placed patrons, the support of his commanding officer, and a widespread recognition of his special talents, and he thus did remarkably well. The obscurity surrounding his background and the questionable side of many of his schemes and actions kept him beyond the pale, however. Although valued in a wartime emergency, he remained a somewhat irregular regular.

[Material concerning John Bradstreet is fairly extensive but widely scattered. The Tredegar Park coll. at the National Library of Wales (Aberystwyth) contains the immensely rewarding Bradstreet-Gould correspondence. At the PAC numerous collections (in microfilm and transcript) touch upon Bradstreet’s activities. Among the more important are the Amherst family papers (MG 18, L4), AN, Col., C11B (MG 1), Nova Scotia A (MG 11, [CO 217]), PRO, Adm.1 (MG 12), CO 5, CO 194, CO 217 (MG 11), PRO 30/8 (MG 23, A2), and WO 1 (MG 13). At the PANS, RG 1, 5–26, 29–30, 34–35, and 38 were helpful. The Clements Library houses the extensive Thomas Gage papers; the American series contains substantial correspondence between Gage and Bradstreet. The American Antiquarian Soc. (Worcester, Mass.) has the John Bradstreet papers, 1755–77, and the New York Public Library, Manuscripts and Archives Division, has the somewhat disappointing Philip Schuyler papers. Both the New York Hist. Soc. (New York) and the New York State Library (Albany) have miscellaneous items dealing with Bradstreet. The Huntington Library has the Abercromby and Loudoun papers, which are worthwhile, particularly the latter, and the Mass. Hist. Soc. has the equally useful Belknap papers.

Among the more important printed primary sources are [John Bradstreet], An impartial account of Lieut. Col. Bradstreet’s expedition to Fort Frontenac . . . (London, 1759; repr. Toronto, 1940); The Colden letter books (2v., N.Y. Hist. Soc., Coll., [ser.3], IX, X, New York, 1876–77); Correspondence of General Thomas Gage (Carter); Correspondence of William Pitt (Kimball); Correspondence of William Shirley (Lincoln); Diary of the siege of Detroit . . . , ed. F. B. Hough (Albany, N.Y., 1860); The documentary history of the state of New-York . . . , ed. E. B. O’Callaghan (4v., Albany, 1849–51), I, IV; G.B., PRO, CSP, col., 1710–11 to 1738; Johnson papers (Sullivan et al.); The Lee papers (2v., N.Y. Hist. Soc., Coll., [ser.3], IV, V, New York, 1871–72), I; Louisbourg journals, 1745, ed. L. E. De Forest (New York, 1932); Mass. Hist. Soc., Coll., 1st ser., I (1792), VII (1800); 4th ser., V (1861), IX (1871), X (1871); 6th ser., VI (1893), X (1899); Military affairs in North America, 1748–65 (Pargellis); NYCD (O’Callaghan and Fernow), VII, VIII, X; Royal Fort Frontenac (Preston and Lamontagne).

Bradstreet has never been examined in a full-length biography. S. McC. Pargellis contributed the brief biographical sketch in DAB. Arthur Pound attempted a more detailed look in Native stock: the rise of the American spirit seen in six lives (New York, 1931), but his account is exaggerated and inaccurate. Harvey Chalmers’ historical novel Drums against Frontenac (New York, 1949) paints a fascinating, albeit largely imaginary, picture. Because of Bradstreet’s participation in so many of the mid 18th-century American military campaigns, he is frequently mentioned but is only rarely subject to detailed examination. Examples are Frégault, François Bigot; L. H. Gipson, The British empire before the American revolution (15v., Caldwell, Idaho, and New York, 1936–70), VII; McLennan, Louisbourg; Pargellis, Lord Loudoun; Usher Parsons, The life of Sir William Pepperrell, bart. . . . (2nd ed., Boston and London, 1856); Rawlyk, Yankees at Louisbourg; Shy, Toward Lexington; Stanley, New France; and Rex Whitworth, Field Marshal Lord Ligonier: a story of the British army, 1702–1770 (Oxford, 1958).

The only recent detailed studies of particular phases of Bradstreet’s career are W. G. Godfrey, “John Bradstreet at Louisbourg: emergence or re-emergence?” Acadiensis, IV (1974), no.1, 100–20, and Peter Marshall, “Imperial policy and the government of Detroit: projects and problems, 1760–1774,” Journal of Imperial and Commonwealth History (London), II (1974), 153–89. A full-length study of Bradstreet’s career in dissertation form is W. G. Godfrey, “John Bradstreet: an irregular regular, 1714–1774” (unpublished phd thesis, Queen’s University, Kingston, Ont., 1974). w.g.g.]

Cite This Article

W. G. Godfrey, “BRADSTREET, JOHN (baptized Jean-Baptiste),” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 4, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed December 31, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/bradstreet_john_4E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/bradstreet_john_4E.html |

| Author of Article: | W. G. Godfrey |

| Title of Article: | BRADSTREET, JOHN (baptized Jean-Baptiste) |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 4 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1979 |

| Year of revision: | 1979 |

| Access Date: | December 31, 2025 |