BURGOYNE, JOHN, known as Gentleman Johnny, army officer, politician, and dramatist; b. 1722, only son of Captain John Burgoyne of Bedfordshire and Anna Maria Burnestone of London; d. 3 Aug. 1792 and was buried in Westminster Abbey, London, England.

John Burgoyne was educated at Westminster School, where he developed an exaggerated classical style and a life-long friendship with Lord Strange, son of the wealthy and powerful 11th Earl of Derby. Commissioned a cornet in the 13th Dragoons in 1740, he purchased a lieutenancy the next year. In 1743 he eloped with Lady Charlotte Stanley, sister of his friend Lord Strange, and her father, after providing a modest dowry, cut her off. Burgoyne bought a captaincy with the money, but by 1747, deeply in debt, he sold his commission and retired with his wife to France. Burgoyne travelled extensively during his stay on the continent and was at this time first exposed to the European concept of “light dragoons” or “light horse,” a type of mounted troops then unknown in England. He later submitted a plan to create such a force and in 1759 raised the 16th Light Dragoons, a light horse regiment.

In 1756, after a reconciliation with his father-in-law, Burgoyne returned to the army with a captaincy in the 11th Dragoons, which he exchanged in 1757 for a captaincy in the Coldstream Foot Guards, which gave him the army rank of lieutenant-colonel. In the Seven Years’ War Burgoyne took part in raids on the French coast and from 1759 served as colonel of the 16th Light Dragoons. He took a radical approach to organization and discipline in his regiment, his views being well in advance of contemporary thought. He made his military name in the Portuguese campaign of 1762, capturing the towns of Valencia de Alcántara (province of Cácerio, Spain) and Vila Velha de Ródão (district of Castelo Branco, Portugal).

The next decade was the height of Burgoyne’s success. Elected to parliament for Midhurst in 1761 through the Derby patronage, he was active in the house on foreign policy and military matters. He received military sinecures worth £3,500 annually, and a promotion to major-general in 1772. He was in the forefront of the great debate on India and the attack on Robert Clive. He also began a literary career and made a considerable success with a play, Maid of the oaks, presented in London by David Garrick in 1775.

At the outbreak of the American revolution Burgoyne was sent to Boston, and there he witnessed the battle of Bunker Hill. Without a field command, he spent much of his time writing letters home which were critical of his commander, Lieutenant-General Thomas Gage. He also wrote a proclamation addressed to the rebels, which was ridiculed both in the colonies and at home for its high-flown language; Horace Walpole later characterized him as “Pomposo” and “Hurlothrumbo.” Burgoyne returned to England in November 1775 and attempted, without success, to get an independent command. He sailed for Quebec in March 1776 with reinforcements for Guy Carleton*, who was besieged by American forces under the command of Benedict Arnold*.

The first of the troops arrived in May, Burgoyne himself late in June. Carleton then followed the Americans in their retreat up Lake Champlain, with Burgoyne as his second in command. In November, at the close of the campaign, Burgoyne returned to England. On 28 Feb. 1777 he submitted to the government his “Thoughts for Conducting the War from the side of Canada.” It was a clear presentation of the campaign attempted in 1776, separation of the New England colonies from the rest by a British advance along the Lake Champlain-Hudson River line of communications. Burgoyne’s plan was adopted almost verbatim and in 1777 the government ordered him to go to Albany, N.Y., there to effect a junction with the forces of Lieutenant-General Sir William Howe; he would thus come into the area of Howe’s responsibility and place himself under Howe’s command. The two men would later have conflicting interpretations of Howe’s intended role at that stage of the campaign. At the same time Lieutenant-Colonel Barrimore Matthew St Leger was to advance towards Albany by the Mohawk valley and capture Fort Stanwix (Rome, N.Y.).

Burgoyne was back in Quebec by 6 May 1777 as the field commander; Carleton’s powers were confined to Canada. Carleton resigned his governorship over this slight, but he nonetheless provided the necessary administrative support to the extent that Burgoyne was able to advance only six weeks after arriving at Quebec. His only real problem was inadequate assistance from the local inhabitants and the subsequent weakness of his transport.

Burgoyne’s army, which gathered at Saint-Jean in June, was composed of about 7,500 regulars, 400 Indians, 100 loyalists, and over 2,000 non-combatants. During the advance up Lake Champlain, Burgoyne made speeches to his Indians and issued proclamations to the Americans, all of which were later ridiculed for their pretension. The British reached Fort Ticonderoga on 30 June and easily forced the Americans to evacuate it. Most of the garrison, however, got away. Burgoyne then moved to Skenesborough (Whitehall, N.Y.) and there made the mistake of advancing to the Hudson River cross-country instead of going via Lake George. It took four weeks to cover 22 miles of difficult terrain, under constant harassment by the enemy.

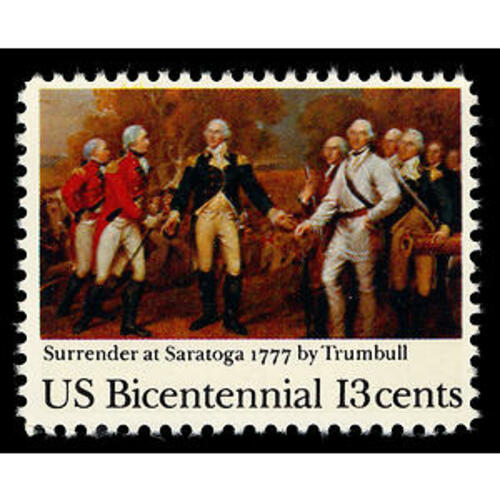

His need for supplies prompted Burgoyne to undertake a disastrous diversion to Bennington (Vt), which cost almost 1,000 men. Nearly stranded in the wilderness, he gathered supplies from the immediate countryside and then crossed the Hudson River on 13–15 September at Saratoga (Schuylerville, N.Y.). The American forces under Major-General Horatio Gates were gathering in strength to the south, and there was an encounter battle nearby in the vicinity of Freeman’s Farm on the 19th. The British suffered heavy losses but held the field, and some commentators say that, had they attacked the next day, they might have won through. Instead, Burgoyne dug in. It appears that at this point he decided that a northern move by Howe was essential. But Howe was operating in Pennsylvania and was unable to come to Burgoyne’s assistance. A second battle was fought nearby at Bemis Heights on 7 October. The British were defeated and fell back on Saratoga. The Americans surrounded them on the 12th, and on the 17th Burgoyne and his army surrendered.

After a winter in Boston with his men, Burgoyne was paroled and returned to Britain. Dropped by the government, he joined the Whigs and in 1780 published his State of the expedition from Canada, an ably argued defence of his campaign and conduct. He regained some of his offices when the Whigs returned to power in 1782, but he lost them again when they fell in 1783. He opposed the younger Pitt and made almost his last political appearance as manager of Warren Hastings’ impeachment in 1787.

Most of his last decade was spent in literary efforts. He wrote the librettos for two comic operas and in 1786 produced his best comedy, The heiress, popular both in Britain and on the continent. Following his wife’s death in 1776, Burgoyne had four illegitimate children by his mistress Susan Caulfield.

Burgoyne was almost an archetypal example of the 18th-century Englishman of public affairs. As a soldier, writer, and politician, he had some ability but not genius. In a society where connections were everything, his were effective but carried him beyond his depth. Scholars still dispute his merits, or lack of them, but because Saratoga is generally accepted as the turning point of the American revolution, Burgoyne remains best known as the general who lost that campaign.

[John Burgoyne], The dramatic and poetical works of the late Lieut. Gen. J. Burgoyne; to which is prefixed, memoirs of the author . . . (2v., London, 1808); Orderly book of Lieut. Gen. John Burgoyne from his entry into the state of New York until his surrender at Saratoga, 16th Oct., 1777 . . . , ed. E. B. O’Callaghan (Albany, N.Y., 1860); A state of the expedition from Canada . . . (London, 1780; repr. New York, 1969). [Roger Lamb], An original and authentic journal of occurrences during the late American war, from its commencement to the year 1783 (Dublin, 1809).

Boatner, Encyclopedia of American revolution. DNB. The Oxford companion to English literature, comp. and ed. Paul Harvey (4th ed., rev. Dorothy Eagle, Oxford, 1967). E. B. De Fonblanque, Political and military episodes . . . derived from the life and correspondence of the Right Hon. John Burgoyne . . . (London, 1876). F. J. Hudleston, Gentleman Johnny Burgoyne: misadventures of an English general in the revolution (New York, 1927). Hoffman Nickerson, The turning point of the revolution, or Burgoyne in America (2v., Boston and New York, 1928; repr. Port Washington, N.Y., 1967). W. M. Wallace, Appeal to arms – a military history of the American revolution (New York, 1951). C. [L.] Ward, The war of the revolution, ed. J. R. Alden (2v., New York, 1952).

Cite This Article

James Stokesbury, “BURGOYNE, JOHN (Gentleman Johnny),” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 4, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed January 2, 2026, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/burgoyne_john_4E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/burgoyne_john_4E.html |

| Author of Article: | James Stokesbury |

| Title of Article: | BURGOYNE, JOHN (Gentleman Johnny) |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 4 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1979 |

| Year of revision: | 1979 |

| Access Date: | January 2, 2026 |