Source: Link

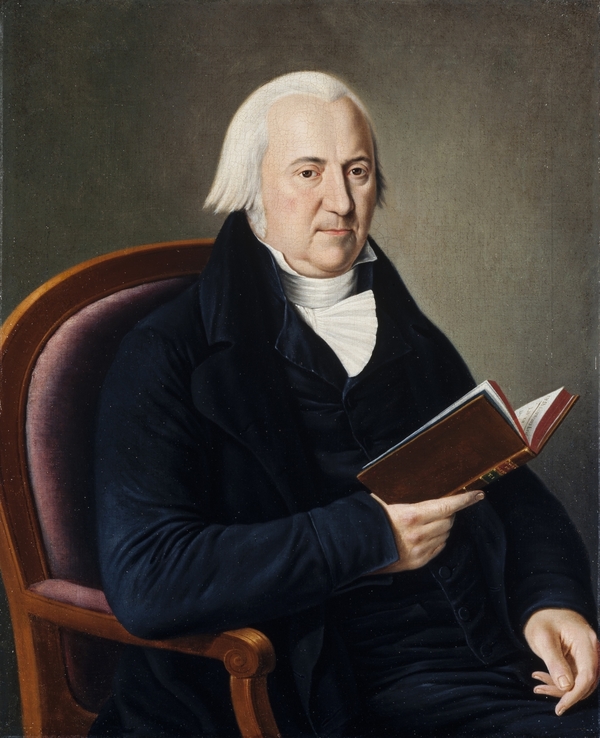

DE BONNE, PIERRE-AMABLE, militia officer, lawyer, seigneur, office holder, politician, judge, and author; b. 25 Nov. 1758 in Montreal (Que.), son of Louis de Bonne* de Missègle, an infantry captain who was killed at Quebec in 1760, and Louise Prud’homme; d. 6 Sept. 1816 in Beauport, Lower Canada.

Pierre-Amable De Bonne is an intriguing figure because of the complexity of his character, thought, and actions, indeed, because of the very contradictions he embodied. A man deeply rooted in the past, he also prefigured the future. As a seigneur he defended his own privileges and those of his class; yet at the same time he knew how to exploit fully the parliamentary institutions he had fiercely opposed. A member of the liberal professions and a politician, he had virtually no equal as an election organizer and political strategist. At the height of his career he was the most important – and most hated – of the “chouayens,” another Canadian party name for the “traitors” and “placemen”; in fact his ambition and initiative did quickly bring him lucrative offices in the public service. He emerged as the leader of the French-speaking section (which dwindled in time) of the administration’s party in the Lower Canadian parliament. He served the government, however, and not the British faction itself. Hence he never qualified the nationalist positions that he had adopted at the outset of his career. Taking inspiration from the most famous philosophes and writers of the Age of Enlightenment, this “cultivated gentleman” found his place in the cultural life of his community through the theatre and journalism. Even though he posed as a practising Catholic after his second marriage, for a long time he had openly led a licentious life which went absolutely counter to the morality of his time, and he did not hesitate to undermine the Catholic clergy’s influence with the government. His uncontested leadership and his remarkable skill made him the most feared adversary of the Canadian party, since with a handful of allies he held the balance of power in a house of assembly in which few members were regularly present until 1808. It was for this reason that the Canadian party was so hostile towards him.

Birth dictates duty. De Bonne purported to descend from the family of the constable François De Bonne, Duc de Lesdiguières, a claim that earned him the gibes of many of his compatriots, particularly in Le Canadien. His father, moreover, had called himself “Sieur de Missègle” and with Louis Legardeur* de Repentigny had acquired the seigneury of Sault-Sainte-Marie in 1750. In 1770, after his death, De Bonne’s mother had married Joseph-Dominique-Emmanuel Le Moyne de Longueuil; Le Moyne would be left two large seigneuries, Nouvelle-Longueuil and Soulanges, by his father, Paul-Joseph Le Moyne* de Longueuil, known as the Chevalier de Longueuil.

De Bonne began his classical studies at the school founded by the Sulpicians in Longue-Pointe (Montreal) and continued them from 1773 at the new Collège Saint-Raphaël in Montreal. In the summer of 1775, having completed his sixth year (Rhetoric), which concluded the course of study then offered at that institution, he entered the Petit Séminaire de Québec for Philosophy, the final two years of the classical program.

During the siege of Quebec by the Americans in the winter of 1775–76 [see Benedict Arnold; Richard Montgomery*], De Bonne took part in the defence of the town as an ordinary soldier in Captain Pierre Marcoux’s company. He became an ensign and in 1776 went on the Lake Champlain campaign; promoted lieutenant, he was taken prisoner by the Americans in 1777, following the surrender of Major-General John Burgoyne*’s army. Upon his release he returned to the province of Quebec, but being unable to obtain adequate compensation from the government was forced out of active service. As a result he realized that a military career offered limited prospects to a French Canadian serving in the militia under the British régime. This perception did not prevent him from accepting the post of lieutenant-colonel of the Quebec militia battalion in 1796, and that of colonel of the Beauport, Charlesbourg, and Côte de Beaupré militia in the autumn of 1809, or from other involvement occasionally, for example delivering a patriotic speech to Colonel Jean-Baptiste Le Comte Dupré’s battalion in the summer of 1807. Soon after returning to the province De Bonne took up the study of law in Montreal, and in January 1780 he asked Governor Haldimand for a commission as a lawyer. He obtained it on 14 March, apparently along with one as a notary.

In 1781 De Bonne rendered fealty and homage for half of the fief and seigneury of Sault-Sainte-Marie, of which he declared himself sole heir. He added to his holdings with the passing years: in December 1784 he signed a petition to the king as “seigneur of Sault-Sainte-Marie and Choisy”; in 1794 he bought for 28,800 livres the sub-fief of Grandpré, on the Route de la Canardière near Quebec, and the following year built a château on it; in 1802 he purchased a property in the seigneury of Notre-Dame-des-Anges, at Beauport, for 3,000 livres, and a lot in the faubourg Saint-Roch at Quebec which he resold in 1806; in addition he rented or sold lots at Montreal and Quebec and had the promise of a property on the south shore of the Rivière Saint-François. These transactions went hand in hand with borrowing (12,000 livres in 1800, for instance) and lending (to the extent of 60,000 livres in 1812 alone), as well as with a standard of living which suggests an unquestionable financial independence that could not have come solely from his emoluments (20,400 livres annually around 1810) as a member of the Executive Council and judge of the Court of King’s Bench.

On 9 Jan. 1781, at Vaudreuil, De Bonne married Louise Chartier de Lotbinière, daughter of the seigneur (and later marquis) Michel Chartier* de Lotbinière and Louise-Madeleine Chaussegros de Léry. The marriage was soon a spectacular failure, with tradition attributing loose conduct to one spouse or other, or to both of them. In 1782, a few months after the death of their only son at five months of age, the couple separated by mutual consent. In 1790 Louise went off to the United States with Charles-Roch Quinson de Saint-Ours, who turned back near the border, and Samuel McKay, by whom she had a son of the same name in Williamstown, Mass.; she died there in 1802. Historians stress that good relationships were maintained between De Bonne and the Chartier de Lotbinière family: witness the agreement in 1804 by which De Bonne relinquished enjoyment of the usufruct of his wife’s property that had been provided for in their marriage contract. However, in 1798 Michel-Eustache-Gaspard-Alain Chartier* de Lotbinière had complained of his brother-in-law’s loose behaviour, claiming, “[He] is running around, [while] his wife is in a deplorable state.” Soon after, De Bonne seduced Catherine Le Comte Dupré, the wife of Antoine Juchereau Duchesnay; this affair ended with a gentleman’s agreement before notary Félix Têtu and Attorney General Jonathan Sewell*. On 16 Jan. 1805 De Bonne took as his second wife 23-year-old Louise-Élizabeth Marcoux, the daughter of André Marcoux, a farmer, and Louise Bélanger, of Beauport; they were married under a contract providing for husband and wife to administer their properties separately, with the guarantee of an annual allowance of 3,000 livres for her in the event of his death. This marriage was regarded by the Canadian party as a self-interested one designed to dispel rumours that De Bonne had joined the ruling British oligarchy.

On the professional level the return of peace in 1783 offered young De Bonne a new field, which he was able to exploit to draw attention to himself and prepare for a long political career. However, his activism cannot be explained by personal ambition alone. His first political contest brought him into a struggle in which the basic stakes went well beyond the aims of a mere careerist. The decision he took to defend the system of government established under the Quebec Act was as much due to a desire to promote the privileges and class interests of the seigneurial gentry to which he belonged as to the sense of nationalism that was developing within this social group in face of the demands of the anglophone bourgeoisie.

To offset the requests for constitutional reform put forward by the British minority, the seigneurial élite of Montreal took the initiative of petitioning the king for a more equitable redistribution of the seats in the Legislative Council; the seigneurs called in question the composition of this political body, claiming that since two-thirds of its members were subjects of Great Britain, the British were assured of “preponderance always,” enabling them to “make changes and alterations [to the] laws . . . in relation to their interests.” But this clearly expressed desire to seize legislative power was to create a deep split among the French Canadian majority between those favouring the creation of an assembly and those defending the established régime. De Bonne rushed into the fray with such determination that he took the lead in a veritable campaign against reform. Indeed, he never stopped fighting until the plan for a new constitution was submitted to the British parliament for approval.

With “the very humble address of the Roman Catholic citizens and inhabitants of different conditions in the province of Quebec” in December 1784, the opening round was fired in the campaign of opposition to the reform movement; De Bonne’s name appeared at the head of the list of signatories. The committee responsible for drawing up this address to the king was composed of the leading members of Montreal’s seigneurial élite: De Bonne, his brother in-law Michel-Eustache-Gaspard-Alain Chartier de Lotbinière, judge René-Ovide Hertel* de Rouville, and legislative councillors Joseph-Dominique-Emmanuel Le Moyne de Longueuil (De Bonne’s stepfather) and François-Marie Picoté* de Belestre. The importance of this manifesto has not escaped historians, who have taken it as a faithful reflection of the conquered people’s views. Duncan McArthur even called it the “first definite declaration of French-Canadian nationalism” and discerned in it a revealing indication of the “essentially conservative character” of that nationalism. Rather it ought to be seen as the ideological expression of the seigneurial class, which had to fight a rearguard action in the hope of retaining privileges from the ancien régime. Linked through his status as a seigneur and his claims of nobility to the fate of a social group in decline, De Bonne in the end fell back on conservative positions, compromising his reputation in the eyes of the rising new professional élite to which he might have belonged had he been of another generation.

The alliance that his reformist compatriots had established with the English-speaking bourgeoisie impelled De Bonne to a vigorous and sustained fight. His opposition was more forceful and energetic because he was conscious of the dangers that the alliance of bourgeois forces in the colony represented for the future of his social group. The choice of Adam Lymburner*, a Scottish merchant from Quebec, as the reformers’ delegate to London was not one to allay the seigneurs’ misgivings. How could they be indifferent in the face of the French-language report in the Quebec Gazette/La Gazette de Québec that Lymburner, by his assertions during his first appearance before a committee of the House of Commons in the spring of 1788, had led the members of parliament to believe that the various classes of the province’s population “unanimously desired the abrogation of the laws of Canada”? The English version of this report was, however, somewhat qualified, stating that the Canadians were “almost unanimous.” In the face of this affront De Bonne and his peers organized a second address to the king in which they boldly declared, “Not once were the great landowners of our nation and the various estates that in general comprise it consulted about making innovations of such importance to their welfare and their common interests.” The same authors also drew up a memorial to the governor, Lord Dorchester [Guy Carleton], in which they denounced the actions of Lymburner in “using their name inappropriately and recklessly.”

The administration of justice constituted a privileged realm in which it was easy for the opponents of reform to show their defensiveness since professional solidarity bound them more effectively than class solidarity. Chief Justice William Smith* was to learn to his cost in 1787 that it was very rash to undertake a reorganization of the judicial system in the face of the opposition of the French party in the Legislative Council and of the judges themselves. The judges’ position was so strongly protected by the established system that Smith was unsuccessful in his attempt to prove their misbehaviour and partiality in the courts of common pleas. The three judges for the District of Montreal, John Fraser, René-Ovide Hertel de Rouville, and Edward Southouse, simply refused to take part in Smith’s inquiry and had themselves represented by none other than De Bonne, their attorney. Thus began the latter’s initiation into his future responsibilities as a judge.

However much he was a gentleman of the ancien régime through his links with the seigneurial gentry, De Bonne belonged none the less to the contemporary world. His rich collection of books reveals a man open to the spirit of the Enlightenment. Although legal tomes occupied an important place, there were also many medical treatises, as well as a great variety of works of history and diverse literary genres. Voltaire and Jean-Jacques Rousseau were represented by more than 50 volumes, Jean-François Marmontel by 17. Abbé Guillaume Raynal’s noted Histoire philosophique et politique . . . , published clandestinely in 1770, was side by side with Louis-Sébastien Mercier’s Tableau de Paris, a 12-volume work published in Paris from 1781 to 1790. Surprisingly, at the time of his death De Bonne owned the 57 volumes of the Annual register, which had begun appearing in London in 1758, the year of his birth.

De Bonne had a marked theatrical bent. With such other Canadians as Joseph Quesnel, Jean-Guillaume De Lisle, and Joseph-François Perrault*, he was a director of the Théâtre de Société which was founded in the autumn of 1789 and successfully completed its initial theatrical season from December 1789 to February 1790 – a first for Montreal. The four shows put on included Molière’s Le médecin malgré lui, Quesnel’s Colas et Colinette, ou le Bailli dupé, and three plays by Jean-François Regnard. Against ecclesiastical censure and the threats of the parish priest of Notre-Dame in Montreal, François-Xavier Latour-Dézery, the directors held their ground. A public debate ensued in the Montreal Gazette and went on until the end of the theatre season. The clergy succeeded, however, in having productions by the Théâtre de Société suspended for a few years. A troupe of the same name gave some performances in the years 1795 to 1797, and presented Beaumarchais’s Le barbier de Séville for the first time in the city. This brief reappearance of theatrical activity in Montreal was followed by a new eclipse which lasted until the turn of the 19th century. The town of Quebec resisted clerical censure better, thanks to the presence of the governor and of royal visitors who liked to amuse themselves with stage entertainment; De Bonne was able to take advantage of their inclinations when he was appointed to the Court of King’s Bench of the District of Quebec.

If De Bonne did not put his acting talents on stage, he used them to advantage in the political arena. Each of his election campaigns gave him the opportunity to display his predilection for public show and for theatrical devices: trenchant speeches, a cultivated oratorical style, publicity material, and addresses in the House of Assembly and elsewhere. The period from 1790 to 1794 was the most fruitful for De Bonne’s professional and political future, although through a curious irony of history these years marked the introduction of the new constitutional régime that he had so violently opposed. He had been a justice of the peace since 1788, but it was his office as clerk of the register of landed property, which he held from 1790 to 1794, that involved him in the workings of the colonial administration. In 1791 he also served as assistant to the French secretary to the governor and Council.

In 1792 De Bonne launched into his first election campaign by running as a candidate with Michel-Eustache-Gaspard-Alain Chartier de Lotbinière, his brother-in-law, in the riding of York just west of Montreal. Being assured of support from the two principal lay seigneurs of the constituency, his brother-in-law Chartier de Lotbinière and his stepfather Le Moyne de Longueuil, and from the polling officer, his friend Hubert Lacroix, at a time when voting took place openly in front of the assembled crowd, De Bonne ventured to campaign for the candidates of his choice in the three ridings of Quebec County, Upper Town, and Lower Town. In his Avis aux Canadiens, of which 350 copies were printed, he warned his compatriots against electing members of the English-speaking bourgeoisie. He urged them to choose only “people of property, importance, and character” who had the same interests as they did. The British response, of which 700 copies were distributed, was a lengthy denunciation of “the insidious insinuations” of the future member from York.

At the opening of the session late in 1792, a third of the assembly’s members were English-speaking. De Bonne immediately attracted attention by trying to force the election of a speaker. He supported Louis Dunière, who had nominated lawyer Jean-Antoine Panet. Despite counter-proposals from the British, who put forward the names of James McGill and William Grant (1744–1805), Panet won by 28 votes to 18. This debate lasted two days. No such short span of time resolved the fundamental question of the status of the French language as against the English in a colonial legislature under the tutelage of the British crown. In January 1793 De Bonne moved a resolution laying down as a basic principle the existence of a threefold duality resulting from the dual origin of the laws (French civil and English criminal laws), and the bi-ethnic composition both of the population and of its representatives in the legislature. It followed that the records of the assembly should be kept in both languages. Since this resolution left undecided the crucial matter of the language of legislation, John Richardson* introduced an amendment that only the English texts of acts and parliamentary debates would be recognized in law. The lengthy debate that ensued gave rise to vehement speeches by the supporters of one or the other proposition: unilingual laws or the legality of both languages. The speeches on the French-speaking side that most impressed people at the time, those by De Bonne, Joseph Papineau*, and Pierre-Stanislas Bédard*, have not been preserved. Their loss is the more regrettable since they might have made it possible to establish important parallels in the realm of nationalist ideology between De Bonne, Bédard, and Papineau at that period. Perhaps they would have revealed why the colonial government had an interest in enlisting De Bonne – the most vindictive of the three – on its side with tempting offers the following year: judge of the Court of Common Pleas on 8 Feb. 1794, judge of the Court of King’s Bench for the District of Quebec on 16 December, and as the crowning gesture member of the Executive Council on New Year’s Eve. This meteoric rise was due less to his career as a lawyer and his professions of loyalty during the popular disorders in 1794 than to his talents as an ambitious, energetic, and popular politician.

As a judge and holder of high office De Bonne had a successful but unremarkable career. In 1797 he showed greater harshness than did his English-speaking colleagues towards 12 Canadians charged with violent resistance to the application of the road law of 1796. In May 1800 Chief Justice William Osgoode* asked Lieutenant Governor Robert Shore Milnes* to dismiss De Bonne from his offices because of his immoral conduct – he accused him of double adultery, then of scandalous talk – and his repeated absences from sittings of the court. At Milnes’s request De Bonne defended himself against the second accusation by affirming that in three years he had been absent only 65 days (25 more, in fact, than the elderly judge Thomas Dunn!). The lieutenant governor took his side with the home authorities: De Bonne’s absences, Milnes said, had not interrupted the court’s sittings and his presence in the assembly was important for the government. In short, the judge’s influence on the electors and the members of the assembly was more important than his personal conduct and his absenteeism.

In 1802 and 1803 De Bonne was empowered to hear some cases involving crimes committed at sea. In 1803 he again showed his attachment to Canadian laws; like his colleague in Montreal, Pierre-Louis Panet, and in opposition to most of the English speaking judges in the colony, he maintained that French law applied in questions of inheritance and dower, even for lands held in free and common socage. London decided in favour of English law in 1804. The following year De Bonne and his colleagues participated in revising police rules and regulations for Quebec. In 1809, along with judges Sewell, Jenkin Williams, and James Kerr*, he prepared the Orders and rules of practice in the Court of King’s Bench, for the District of Quebec, Lower Canada, the publication of which prompted the assembly to initiate impeachment proceedings against Sewell in 1814. In 1810 he again helped revise the police rules and regulations for Quebec. He retired in 1812 and gave up his seat to judge Jean-Olivier Perrault*.

De Bonne made his career primarily in politics. His talents as an organizer and a skilful orator, indeed as a demagogue, won him election to the assembly from 1792 until 1810 without interruption. If Bédard was unquestionably the first French Canadian to make a profession of politics, De Bonne may be considered the first professional political schemer in Lower Canada. His rapid advancement in public office, his ostentatious loyalism, his steady support for government measures in the house, his unquestionable influence on voters and on some Canadian “placemen” in the assembly, the apparent abandonment of his nationalism of the 1780s and 90s, earned him the resentment and then the ferocious hostility of those in the Canadian party. He returned their feelings. Nothing, however, lends support to the theory that he gave up his nationalist position, witness his stand on civil laws concerning lands in free and common socage (1803) and his attitude in the assembly whenever Canadian laws seemed threatened. De Bonne was the system’s man: he got along well in it and defended it; he shared its aristocratic and conservative values; he feared the social threat that the rise of the new professional bourgeoisie and its values represented for society. Unless it is seen in this light, the bitterness of the struggles of the years 1800–10 is incomprehensible. Behind the opposition between men and parties, diverse conceptions of society, government, and power were embodied in the combatants; different ideas of the nation also emerged, as De Bonne’s adhesion to the seigneurs’ nationalism in the period 1780–90 demonstrated.

De Bonne’s political career was long and varied. Besides participating in the early debates of 1792–94 he sat on numerous committees, one of which urged that the Jesuit estates be used for educating the Canadians. In 1794 he introduced a bill for the arrest and detention without trial of people accused or suspected of treason; through an irony of history, this law would serve to imprison the chief editors and the printer of Le Canadien in March 1810 [see Sir James Henry Craig; Pierre-Stanislas Bédard]. A member for York from 1792 to 1796, he was elected in 1796 for Three Rivers after being defeated in the riding of Hampshire. When the session opened in 1797, the judge and assemblyman proposed John Young as speaker of the house, but Panet was re-elected by 29 votes to 12.

De Bonne was re-elected in the same riding in 1800, after being defeated in Northumberland; at the opening of parliament he was nominated for speaker, but he too lost to Panet. During the 1801 session he presented two petitions in the name of his constituents: the first asked that a second judge be appointed for Three Rivers and that four sessions of the Court of King’s Bench be held annually; the second requested that a public school be set up. He also played a leading role in the expulsion of Charles-Jean-Baptiste Bouc* in 1801, 1802, and 1803, despite the efforts of a segment of the Canadian party led by Bédard and Michel-Amable Berthelot Dartigny. The coalition of the British and Canadian placemen led by De Bonne got the better of the Canadian party, which was weakened by the absence of its members on very close votes, for example 12 to 10 and 8 to 7. During the long debates on the creation of the Royal Institution for the Advancement of Learning, De Bonne sided regularly with the government, except in the case of the amendments to protect the existing Canadian schools and institutions.

In 1802 the real weakness of the Canadian party, despite its theoretical majority, led it to propose, as in 1799, a bill to grant an “allowance” to the speaker and members of the assembly. De Bonne proved the fiercest opponent of the measure, making skilful use of procedure and demagoguery, so that the house had to postpone discussion of the bill indefinitely. The bitter opposition by the administration’s party was explained by the fact that it held the balance of power in several critical debates.

In 1804 De Bonne ran against Jean-Antoine Panet in Upper Town. Faced with certain defeat, he withdrew and ran in the riding of Quebec County, where he was elected. His address to the voters is a good example of his theatrical sense and effective demagogic techniques: he mentioned that he had sacrificed his desire to retire to the “honourable preference” of his constituents, who, despite the “scandalous poison” spread about by his enemies, had shown that the people supported the participation of judges in politics. He intended, consequently, to uphold the government’s rights against abuses, corruption, and attacks upon liberty.

De Bonne did not take part in the great debates in 1805 and 1806 on the building of new prisons. But at the end of 1806 he became involved in the founding of Le Courier de Québec, a newspaper combining passionate denunciations of the Canadian party and its organ, Le Canadien, with literary and philosophical texts from the Enlightenment. Le Courier de Québec none the less defended “the Canadian nation,” “Canadian education,” and the French language, among other things, and even denounced the monopolizing of positions and trade by some of the British. Was this approach so far removed from the seigneurs’ recriminations in 1784?

In 1807 De Bonne succeeded through obstructive methods in blocking the bill proposed by the Canadian party for “payment of members” of the assembly. According to the judge this measure might attract scoundrels, as well as people unfit for seats because of lack of education, character, and property. By contrast he praised voluntary service. It was not surprising that in the following session the Canadian party secured the adoption of a bill making judges ineligible to sit in the house, which was rejected by the Legislative Council. Despite what was said about the necessity of keeping justice and judges above all suspicion, the objectives of the Canadian party were more clearly evident when it expelled the Jewish assemblyman Ezekiel Hart*, who belonged to the British party, because he had taken the oath in accordance with the forms prescribed by his religion rather than by the 1791 constitution. In the ensuing elections in June 1808 the Canadian party called upon voters to elect only members “independent of the government and the Legislative Council.” It attacked De Bonne through articles and manifestos in Le Canadien: the basest motives were imputed to him, his dissolute conduct was raked up, and his objectivity as a judge was called in question. De Bonne and his allies brought about the defeat of Jean-Thomas Taschereau* and Jean-Antoine Panet, but Panet was rescued in Huntingdon riding. As for De Bonne, he was one of the few members of the administration’s party who did not go under: beaten in Northumberland, he was re-elected in Quebec County.

In the 1809 session De Bonne vainly tried to have Denis-Benjamin Viger* elected speaker. The Canadian party again brought forward the bill on the ineligibility of judges. De Bonne fought back, using all the resources of his vast parliamentary experience. At the moment when a house committee was tabling a report that was damning for him, the judge was saved by the sudden prorogation of parliament by an enraged Governor Craig. The 1809 elections took place in a highly charged atmosphere. The Canadian party and its newspaper bore down even more on placemen and in particular De Bonne, for their corruption, cynicism, demagoguery, and “undue influence” on voters. De Bonne was even accused by one of his alleged mistresses of having boasted that he had “duped” the Canadians, “their wives, their priests, their religion, and their pope.” All the same, De Bonne weathered the storm and was re-elected by acclamation in Quebec County. In the 1810 session, however, tired of this fencing and confident of receiving London’s support, the assembly declared De Bonne’s seat vacant on a simple resolution. Craig again dissolved parliament. In the ensuing elections De Bonne tried to obtain nomination, but a voters’ meeting chose other candidates. The seizure of Le Canadien and the arrest of its chief editors and its printer gave De Bonne and his friends the opportunity to denounce the Canadian party’s “sedition” in their newspaper, Le Vrai Canadien, and to seek votes, though with little success, for the government’s candidates.

In 1812 De Bonne retired to his estate of La Canardière, whose château and gardens Joseph Bouchette* praised. The Centre Hospitalier Robert-Giffard is now on the site of the château. De Bonne did not retire fully, since he was appointed a commissioner to receive the oath of allegiance in 1812 and 1814 and a member of the commission to administer the Jesuit estates in the summer of 1815. He also acted as agent for four other commissioners.

De Bonne had several differences with the clergy. In 1797 his attempt to create a new parish between Nicolet and Bécancour by legislative enactment earned him the ill will of the Catholic hierarchy and the hostility of Governor Prescott, who considered him “a great enemy” of the church and “a very bad subject.” In 1809 De Bonne wrote to Craig objecting to the excessive liberty enjoyed by the Catholic Church and accusing Bishop Plessis* of having taken advantage of the governor’s absence on a trip to go, ahead with the creation of a new parish. Strangely enough, he was appointed a commissioner with authority to build and repair churches in 1799 and 1805. Given his behaviour and the material in his library, it is ironic that De Bonne is reported to have become “devout” after his second marriage.

De Bonne was a member of the high society of his time; he signed numerous addresses of good wishes to various governors and important people, and in 1794 he assisted at the anniversary dinner of the veterans of the siege of Quebec. He was a member of the Quebec Fire Society from 1795 until 1808, and subscribed to the fund set up to support Britain’s war effort in 1794 and to the Waterloo fund in 1815.

De Bonne died at his estate on 6 Sept. 1816. Burial took place on 10 September in the church of La Nativité-de-Notre-Dame at Beauport, with a host of persons of consequence in the colony, both Canadian and British, in attendance. A deed dated 9 Dec. 1816 mentions a distant relative, Marie-Anne Hervieux, wife of Jean-Baptiste-Melchior Hertel de Rouville, as his sole heir. As for the judge’s widow, in 1816 she asked the government, in vain, for a pension. She hanged herself in a hospital for the insane in 1848, when suffering from a severe anxiety attack.

Pierre-Amable De Bonne is the author of Précis ou abrégé d’un acte qui pourvoit à la plus grande sûreté du Bas-Canada . . . (Québec, 1794). Tremaine, Biblio. of Canadian imprints, describes broadsheets he published during election campaigns for the Lower Canadian assembly.

ANQ-Q, CN1-16, 11 juin 1806, 2 août 1816; CN1-26, 8 mai 1800, 30 avril 1807; CN1-92, 23 juin 1794; CN1-99, 16 janv. 1805; CN1-178, 12 mai 1802; CN1-224, 26 août 1789; CN1-230, 14 juill., 5 sept. 1792; 15 févr., 30 avril, 15 mai 1799; 14 févr., 12 juin, 10 oct. 1800; 28 janv., 20 oct. 1801; 25 juin 1803; 16 mars 1804; 6 juill. 1812; 9 déc. 1816; 13 juill. 1818; P-239. Arch. de la chancellerie de l’archevêché de Montréal, 901.012. McGill Univ. Libraries (Montreal), Dept. of Rare Books and Special Coll., ms coll., CH304.S264. PAC, MG 11, [CO 42] Q, 83: 23, 193; 85: 165, 172,180–88; 86–1: 142; 89: 2; 92: 159–60; 93: 194–95; 98: 270; MG 23, GI, 6; MG 24, B2: 78–81; MG 30, D1, 10: 97–260; RG 1, L3L: 40180–316; RG 4, A1: 17667, 24529; RG 8, I (C ser.), 15: 2–5; 199: 4–5; 688E: 474; 689: 188; 1714: 101; RG 68, General index, 1651–1841: ff.2, 8, 83–88, 223, 229, 259, 280–345, 532, 535. Bas-Canada, chambre d’Assemblée, Journaux, 1793, 1800–12. Doc. relatifs à l’hist. constitutionnelle, 1759–1791 (Shortt et Doughty; 1921). Doc. relatifs à l’hist. constitutionnelle, 1791–1818 (Doughty et McArthur; 1915). Le Canadien, 1806–10. Le Courier de Québec, 1806–8. Quebec Gazette, 1786–1818. Le Vrai Canadien (Québec), 1810–11. F.-J. Audet et Fabre Surveyer, Les députés au premier Parl. du Bas-Canada, 95–153. Hare et Wallot, Les imprimés dans le Bas-Canada. “Papiers d’État,” PAC Rapport, 1890–93. P.-G. Roy, Inv. concessions, 5: 73. A. W. P. Buchanan, The bench and bar of Lower Canada down to 1850 (Montreal, 1925), 57–58. Baudouin Burger, L’activité théâtrale au Québec (1765–1825) (Montréal, 1974). Chapais, Cours d’hist. du Canada, 2: 63–67, 187–95. Christie, Hist. of L.C., 1: 126, 177, 200–1, 230. Duncan McArthur, “Canada under the Quebec Act,” Canada and its prov. (Shortt and Doughty), 3: 122–23. Maurault, Le collège de Montréal (Dansereau; 1967). Ouellet, Bas-Canada. Tousignant, “La genèse et l’avènement de la constitution de 1791.” J.-P. Wallot, “Le Bas-Canada sous l’administration de sir James Craig (1807–1811)” (thèse de phd, univ. de Montréal, 1965); Un Québec qui bougeait. “La bibliothèque du juge De Bonne,” BRH, 42 (1936): 136–43. Bernard Dufebvre [Émile Castonguay], “Une journée de M. De Bonne,” Rev. de l’univ. Laval (Québec), 10 (1955–56): 304–18, 405–25, 524–50. Ignotus [Thomas Chapais], “Notes et souvenirs,” La Presse (Montréal), 1er oct. 1904: 8; 26 nov. 1904: 8; 24 déc. 1904: 9; 14 janv. 1905: 16; 21 févr. 1905: 7; 19 avril 1905: 8. É.-Z. Massicotte, “Un théâtre à Montréal en 1789,” BRH, 23 (1917): 191–92. P.-G. Roy, “L’indemnité de nos députés,” BRH, 10 (1904): 118–22. Benjamin Sulte, “Jean-Baptiste Cadot,” BRH, 6 (1900): 83–86. Pierre Tousignant, “La première campagne électorale des Canadiens en 1792,” SH, 8 (1975): 120–48.

Cite This Article

Pierre Tousignant and Jean-Pierre Wallot, “DE BONNE, PIERRE-AMABLE,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 5, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed April 8, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/de_bonne_pierre_amable_5E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/de_bonne_pierre_amable_5E.html |

| Author of Article: | Pierre Tousignant and Jean-Pierre Wallot |

| Title of Article: | DE BONNE, PIERRE-AMABLE |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 5 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of revision: | 1983 |

| Access Date: | April 8, 2025 |