Source: Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

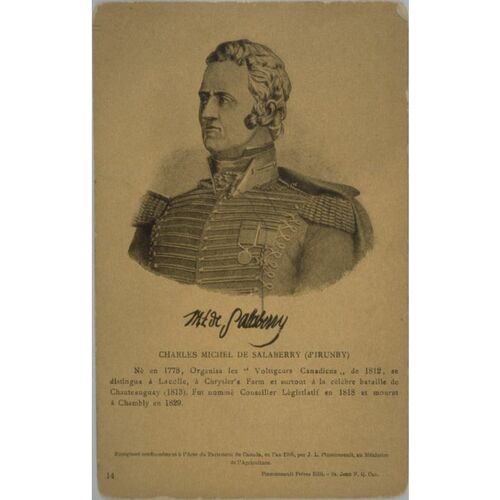

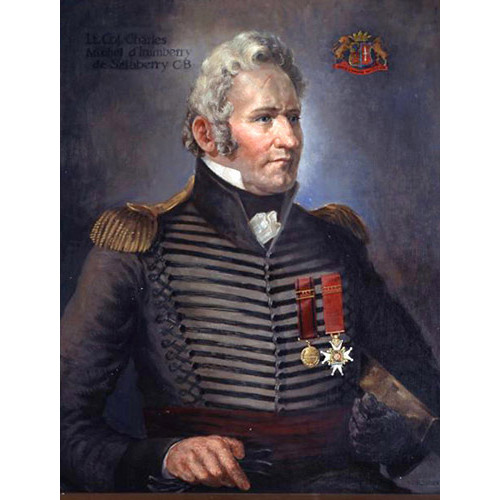

IRUMBERRY DE SALABERRY, CHARLES-MICHEL D’, army and militia officer, politician, seigneur, office holder, and jp; b. 19 Nov. 1778 in Beauport, Que., eldest son of Ignace-Michel-Louis-Antoine d’Irumberry de Salaberry and Françoise-Catherine Hertel de Saint-François; m. 13 May 1812 Marie-Anne-Julie Hertel de Rouville, daughter of Jean-Baptiste-Melchior Hertel* de Rouville, in Chambly, Lower Canada, and they had four sons and three daughters; d. there 27 Feb. 1829.

Charles-Michel d’Irumberry de Salaberry enlisted at the age of 14 as a volunteer in the 44th Foot. In 1794, through Prince Edward* Augustus, a family friend, he received an ensign’s commission in a battalion of the 60th Foot stationed in the West Indies. After his arrival on 28 July that year, he distinguished himself by his bravery in the invasions of the French colonies of Saint-Domingue, Guadeloupe, and Martinique. During this time the prince, having become commander of the military forces in the Maritime colonies, undertook to obtain a lieutenancy for him in his own regiment, the 7th Foot, which was stationed at Halifax. On learning that Salaberry had already been promoted to that rank in the 60th, where advancement was swifter, he asked for the appointment to the 7th to be cancelled and in the interim had him sent home to Lower Canada on leave.

Salaberry’s readmission to the 60th came through too late for him to sail for the West Indies. After being shipwrecked on St John’s (Prince Edward) Island he was detained at Halifax, in the prince’s service. The prince initiated him into freemasonry, and on 2 Feb. 1797 Salaberry was installed as master of Royal Rose Lodge No.2. From March till the end of June he served as a lieutenant on the Asia, which was chasing Spanish ships. He returned to the West Indies at the beginning of July and was garrisoned in Jamaica. Although the prince recommended him several times for a captaincy, Salaberry, who did not have the means to buy the commission, had to wait until the end of 1799 to receive the rank of captain-lieutenant, without a company, in the 60th Foot. On 18 June 1803 he finally obtained a company in the 1st battalion.

In 1804 Salaberry asked the prince – now the Duke of Kent – to use his influence to get him sick leave; he arrived at Quebec on 24 October. On 26 June of the following year he sailed for England with his brothers Maurice-Roch and François-Louis, both of whom had been promoted lieutenant in the duke’s regiment. The three were warmly received at home by Edward Augustus and his companion, Mme de Saint-Laurent [Montgenet], and the duke immediately took steps to have Salaberry exchanged into a different regiment to spare him another tour of duty in the West Indies. In the mean time Edward got several weeks’ leave for him, gave him lodging, invited him to supper every day, and let him use his box at the theatre.

Early in 1806 Salaberry was transferred to the 5th battalion of the 60th Foot, under Colonel Francis de Rottenburg. At the duke’s request he conducted recruiting in Britain for the 1st Foot between July 1806 and March 1807. Major-General Sir George Prevost* created difficulties for him, but to the duke’s great pleasure he none the less succeeded in enlisting more than 150 men. In August 1806 the youngest Salaberry brother, Édouard-Alphonse*, arrived in England. The Salaberrys met only a few times, however, since Maurice-Roch and François-Louis left for India on 18 April 1807. For his part, Charles-Michel was called to Ireland in August. In 1808 he was appointed brigade-major of the light infantry brigade commanded by Rottenburg which in 1809 was dispatched to the Netherlands. Like a number of his comrades, Salaberry caught a contagious fever in that disastrous campaign and returned to England in October. He was transferred back to the 60th Foot, 1st battalion, and in June 1810 learned that he would soon be leaving for the Canadas. There, in the autumn, he became aide-de-camp to Major-General Rottenburg.

On 2 July 1811 Salaberry was promoted brevet major. Seven months later, with the international situation pointing to the imminence of war, he put forward a plan to set up a militia corps, the Voltigeurs Canadiens. In the circumstances Prevost, who had become governor-in-chief in October 1811, could only commend Salaberry, who had the influence, zeal, and energy to raise a corps of volunteers and turn it quickly into an efficient and competent unit. Salaberry began recruiting for this “Provincial Corps of Light Infantry” on 15 April 1812.

Obtaining experienced officers for the militia was not easy, since a man’s absence from his regiment held up his promotion in the army. Furthermore, a militia officer was subordinate to an officer of the regular army holding the same rank – hence Salaberry’s anger when Prevost commissioned him a lieutenant-colonel in the militia, effective 1 April 1812, instead of giving him an army rank. But on 29 Jan. 1813 Rottenburg informed him that he was to have a supervisory function in the Voltigeurs Canadiens with the rank of Lieutenant-colonel in the army. When, contrary to expectations, this rank was not confirmed, Salaberry had to be satisfied with receiving that of lieutenant-colonel of the Voltigeurs Canadiens, on 25 March 1813. Confirmation that he had the same rank in the army did not come until July 1814. Although the militia was subordinate to the army, some army officers insisted upon being taken on in the Voltigeurs Canadiens. They did so for two reasons: the virtual certainty of the militia unit becoming a regular army unit and their rank being recognized, and the desire of some to retire from the army with a militia officer’s salary added to their half pay. Salaberry was thus able to obtain several experienced officers.

At the beginning the recruitment of militiamen succeeded beyond all hopes, on account of the economic crisis, Salaberry’s reputation, and the fact that the Select Embodied Militia had not yet been raised. Notwithstanding the claims sometimes made, exaggerated notions that Salaberry deserves all the credit for recruiting and that the unit was raised in two days are not tenable. In April 1812 the target was a corps of 500, but Prevost reduced the number to 350 in June, and to 300 the next month. In fact, financial circumstances did not permit the Voltigeurs Canadiens and the Glengarry Light Infantry Fencibles to be raised at the same time. With 264 men recruited in the first three weeks, enlistment promised to be easy. But the harshness of military life apparently led many discouraged recruits to desert, for numbers dropped from 323 in June to 270 in October. Salaberry had difficulty mustering 438 men in March 1813. Nevertheless, at the battle of Châteauguay the following October the Voltigeurs Canadiens had 29 officers and 481 non-commissioned officers and men.

Salaberry was a strict and conscientious commander. His officers did not always possess the same qualities. Jacques Viger*, a captain who was later to retain his company through Salaberry’s intervention, often regretted his commission, complaining of the severe discipline and the onerous financial charges that the officers had to assume. Salaberry’s brother-in-law, Jean-Baptiste-René Hertel* de Rouville, who was also a captain in the Voltigeurs Canadiens, begged the adjutant general of militia to transfer him to another regiment because he found his commanding officer too demanding.

On 18 June 1812 the United States had declared war on Great Britain, and the Americans were making ready to invade the Canadas. To defend Lower Canada, in May the government had conscripted the men to form four battalions of Select Embodied Militia; a fifth was created in September, and another in February 1813. The sedentary militia took training and on occasion was called up. Besides the Voltigeurs Canadiens a number of voluntary militia units were raised, sometimes for brief periods. In November 1812 an attempted invasion near Lacolle brought the Voltigeurs Canadiens into action. On 27 November Salaberry was praised for his conduct in commanding the advance guard. But in July 1813 he learned that Prevost had sent the British government a dispatch on the events making no mention of his name and congratulating the adjutant general, Edward Baynes, and Major-General Rottenburg, who had taken no part in the action.

Early in August the Voltigeurs Canadiens covered the withdrawal of the British ships sent to burn the barracks in Swanton, Vt, two blockhouses at Champlain, N.Y., and the barracks and arsenal north of Plattsburgh. In October Salaberry was sent to Four Corners, near Châteauguay, with a handful of soldiers and some Indians to reconnoitre the enemy forces and attack. However, there were not enough men and the plan fell through.

Disappointed with the missions being given him, Salaberry wanted to leave the army. But then he was summoned to proceed in all haste from Châteauguay with his troops to the river of that name. The Americans were preparing to attack Montreal in order to cut off the British army in Upper Canada. On 21 October Major-General Wade Hampton crossed the border at the head of some 3,000 men and advanced up the Châteauguay towards Montreal, which he and Major-General James Wilkinson, who was coming down the St Lawrence from Sackets Harbor, N.Y., were to attack.

Having foreseen that the enemy would cross the Châteauguay at Allan’s Corners, on the east bank, Salaberry had an abatis thrown up at the spot. There he placed about 250 of the Voltigeurs Canadiens, the sedentary militia, and the Canadian Fencibles, along with some Indians. He sent 50 men from the sedentary militia and from the 3rd battalion of the Select Embodied Militia across the river. A mile behind the abatis about 1,400 militiamen under Lieutenant-Colonel George Richard John Macdonell* were divided among four entrenchments one behind the other.

When he reached Ormstown, some miles from the abatis, Hampton split his troops; he sent about 1,000 men across the Châteauguay and himself advanced with 1,000 or so, leaving a like number in reserve at his encampment. The American troops did not manage to surprise Salaberry’s militiamen. By shrewd tactics Salaberry had succeeded in creating the illusion that his force was much stronger than it actually was and thus discouraged the enemy. After about four hours of fighting on 26 October, Hampton ordered his troops to retreat. The Canadians remained at the abatis, ready to resume combat the following day. But Hampton, who had received orders to take up winter quarters in American territory, thought that his superior, Major-General Wilkinson, had called off the attack on Montreal, and he moved his troops back towards the United States. His actions were based on a misunderstanding, but having learned of Hampton’s defeat and withdrawal, Wilkinson did not want to attack Montreal. The battle of Châteauguay therefore saved that town from a large-scale attack [see Joseph Wanton Morrison].

Salaberry’s superior, Major-General Abraham Ludwig Karl von Wattenwyl*, and Prevost arrived at the same time to observe the enemy’s retreat. After the battle, relying on prisoners’ estimates, the Canadians thought they had faced 6–7,000 Americans. In reality some 3,000 Americans had met about 1,700 Canadians. According to Prevost’s report, written on the day itself, about 300 Canadians had opposed 7,500 Americans. From that time, the battle of Châteauguay took on a legendary character and became a source of popular pride: the Canadians, commanded by one of their own, had displayed their bravery, their military capacity, and their loyalty in repelling the Americans.

If people found reasons for pride in Prevost’s general order, Salaberry saw in it an intention to cheat him of credit for the victory. Indeed, Prevost said that he himself had been present at the battle and gave Wattenwyl credit for the strategy employed. Humiliated and denied his rights, Salaberry made innumerable attempts to obtain recognition from the authorities and a promotion in the army. But confronted with the attitudes taken by Prevost and by the Lower Canadian parliament, which in the absence of the governor’s assent, did not dare give the usual expression of thanks, Salaberry, who was tired and ill, enquired at the end of 1813 about the terms for retirement from the army. He asked his father to moderate his ambitions for him: he could never become a general officer, because he was a Catholic and because advancement would require 10 or 12 years’ more experience. In January 1814 he offered his commission to Frederick George Heriot* for £900. After finally receiving the thanks of the House of Assembly on 30 January and those of the Legislative Council on 25 February, he was still thinking of retiring when he learned on 3 March that Prevost was to recommend him for appointment as inspecting field officer of militia. This promotion promised monetary gain and interesting work. He left the Voltigeurs Canadiens with some regrets, and Heriot replaced him in his command.

In a letter of 15 March Prevost did indeed recommend Salaberry for appointment as inspecting field officer, but in a confidential report dated 13 May he disparaged him, accused him of negligence, and claimed that he had only been carrying out Wattenwyl’s orders; in so doing he robbed him of any credit for the victory at Châteauguay. Salaberry had, then, good reason to be wary of Prevost’s duplicity, and the appointment was not confirmed. Therefore, having carried out the duties for several months, he sent in his resignation. It was intercepted by the Duke of Kent, to the good fortune of Salaberry, who continued to receive an army lieutenant-colonel’s pay. He retained his appointment as inspecting field officer, and also remained lieutenant-colonel of the Voltigeurs Canadiens, his service being interrupted by a 42-day stint on the court martial of Henry Procter. The war ended on 24 Dec. 1814, but the news did not reach the colony until the spring. The militia was demobilized in March 1815. Once the troops had been discharged, Salaberry turned his attention for several months to obtaining his own pay; he also took steps on behalf of the militiamen entitled to payments and the wounded who were to receive compensation.

In 1816 Salaberry received a medal commemorating the battle of Châteauguay. Then, on 5 June 1817, he learned that as result of a recommendation from Sir Gordon Drummond* and Macdonell’s friendly intervention, he had been made a companion of the Order of the Bath. In December, Governor Sir John Coape Sherbrooke recommended him to replace Jean-Baptiste-Melchior Hertel de Rouville, his father-in-law, on the Legislative Council. His appointment dated from December 1818, and he took his seat on 19 Feb. 1819. His father was already a member of the council and thus, for the first time, a father and son served together on it.

In 1814 Salaberry had gone to live in Chambly. In July the Hertel de Rouvilles gave the Salaberrys some land near the military reserve. Then Salaberry’s father handed over to him the 2,000 livres that his godfather, vicar general Charles-Régis Des Bergères de Rigauville, had bequeathed him. Salaberry therefore found himself in possession of a sizeable estate; he managed it conscientiously, claiming compensation for the depredations his lands had been subjected to during the war and bringing lawsuits against several of his neighbours and censitaires to establish the boundaries of his lands and full possession of them.

The death of Pierre-Amable De Bonne* in 1816 enabled Salaberry to add to his fortune, since his mother-in-law, Marie-Anne Hervieux, was a relative of the judge. Having conferred power of attorney on her son and son-in-law to get possession of De Bonne’s estate, she handed the property over to them and to her daughter in March 1817. This gift was made not long before Jean-Baptiste-Melchior Hertel de Rouville’s death on 30 Nov. 1817, which was followed by his wife’s on 25 Jan. 1819. Management of their estate was entrusted to Salaberry. Salaberry’s wife had inherited the fief of Saint-Mathias, and on 5 Nov. 1819 Salaberry bought the adjoining fief of Beaulac from William Yule. Salaberry’s brother-in-law, who was in financial difficulties, sold him and his wife part of his inheritance, including the flour-mill at Saint-Mathias. In January 1818 Salaberry had bought the rights on the part of the king’s domain located in the seigneury from Samuel Jacobs, who was the seigneur of part of Chambly. Finally, when Jacobs went bankrupt in 1825, he bought his land and so was able to extend his own property. He profited from his holdings and in addition lent money.

Salaberry was also interested in transportation. With his friend and neighbour Samuel Hatt and several merchants and private individuals from the Richelieu region he founded a company in October 1820 to build the steamship De Salaberry. It was launched on 3 Aug. 1821, to ply between Quebec, Montreal, and Chambly. On 12 June 1823 the ship burned off Cap-Rouge; six or seven people perished and an extremely valuable cargo was lost.

In 1815 Salaberry had been appointed a justice of the peace for the District of Quebec. He received a similar commission for the districts of Montreal, Trois-Rivières, and Saint-François in 1821, and for the district of Gaspé in 1824. On 14 May 1817 he had been given responsibility for improving communications in Devon County, being named commissioner of roads and bridges. Although he was an illustrious member of the Legislative Council, he was more conspicuous by his absence than by his participation. He supported the petition against the Union Bill of 1822, but in 1824 he wrote to Viger that he expected the union of Upper and Lower Canada to come about.

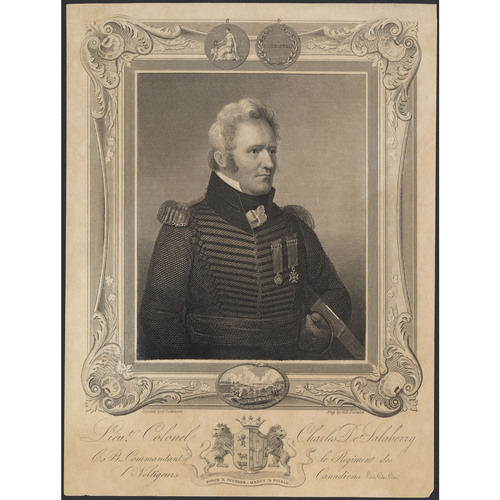

That year Viger, who had become a friend of his former commander, undertook to raise a subscription to have an engraving done of Salaberry, “whose name is already part of history.” The engraver, Asher Brown Durand of New York, did the portrait from a miniature by New York artist Anson Dickinson.

Salaberry was a man of impetuous temperament Rottenburg called him “my dear Gunpowder.” He was also pleasant, straightforward, and warmhearted. Stricken by an attack of apoplexy while supping at Hatt’s, he died on 27 Feb. 1829.

The name of Charles-Michel d’Irumberry de Salaberry was, however, not to be forgotten. His role in the battle of Châteauguay, much disputed even during his lifetime, would be viewed in many different ways as Lower Canadian society evolved. In the mid 19th century he was perceived as an experienced, courageous, intrepid soldier who enjoyed the confidence of his men. At the turn of the century English-speaking historians put greater emphasis on the roles played by Macdonell or Wattenwyl, but French-speaking ones defended Salaberry, stressing his valour and intrepidity and pointing out that he had had to make do with limited means furnished by pusillanimous superiors. In the early 1950s Salaberry was looked upon as the French Canadian who had given an outstanding demonstration of the courage of the race. In the decade that followed, the portrait of the hero was effaced by the image of a body of national militia including both English- and French-speaking men who side by side defended Canada. Finally, more recently Salaberry’s victory has been attributed to a fruitful collaboration by various elements against a common enemy.

AAQ, 210 A, VIII. ANQ-M, CN1-16, 21 mars 1814; CN1-43, 16 mai, 6, 30 juill., 7, 23 sept. 1814; 4 oct., 9 nov., 24 déc. 1816; 10 janv. 1817; 29 juin 1818; 1er, 5 févr., 30 avril, 5 juill. 1819; 23 mai, 4, 18 juill., 4 oct. 1820; 23, 26 janv. 1822; CN1-123, 14 sept. 1816; 29 juill. 1817; 27 janv. 1818; 30 oct. 1820; 29 juin, 21 juill., 6 août 1821; 28 mars 1822; 26 mars, 3 juill. 1823; 2 févr. 1825; CN1-194, 13 mai 1812, 25 janv. 1814. ANQ-Q, CE1-5, 19 nov. 1778; CN1-212, 28 avril 1816; E21/12; P-289; P-417. ASQ, mss, 74. National Arch. (Washington), RG 94. PAC, MG 24, B2; B16; G5; G8; G9; G45; L5; RG 1, E2, 3; L3L; RG 4, A2; B21; RG 8, I (C ser.); RG 9, I; II, A4; A5. W. F. Coffin, 1812, the war and its moral; a Canadian chronicle (Montreal, 1864). William James, A full and correct account of the military occurrences of the late war between Great Britain and the United States of America . . . (2v., London, 1818). L. C., House of Assembly, Journals, 1819, app.O; Legislative Council, Journals, 1814, 1818, 1819; Statutes, 1793–1814. The life of F.M., H.R.H. Edward, Duke of Kent, illustrated by his correspondence with the De Salaberry family, never before published, extending from 1791 to 1814, ed. W. J. Anderson (Ottawa and Toronto, 1870). Official letters of the military and naval officers of the United States, during the war with Great Britain in the years 1812, 13, 14, & 15 . . . , comp. John Brannan (Washington, 1823). [James Reynolds], Journal of an American prisoner at Fort Malden and Quebec in the War of 1812, ed. G. M. Fairchild (Quebec, 1909). Select British docs. of War of 1812 (Wood). Montreal Gazette, 9 Nov. 1813. Quebec Mercury, 1805–14. F.-M. Bibaud, Le Panthéon canadien (A. et V. Bibaud; 1891). L.-O. David, Biographies et portraits (Montréal, 1876), 59. Montreal almanack, 1829. H. J. Morgan, Sketches of celebrated Canadians. Quebec almanac, 1811–14. Gilbert Auchinleck, A history of the war between Great Britain and the United States of America, during the years 1812, 1813, and 1814 (Toronto, 1855). F. F. Beirne, The War of 1812 (Hamden, Conn., 1965). H. L. Coles, The War of 1812 (Chicago, 1965). L.-O. David, Le héros de Châteauguay (C. M. de Salaberry) (Montréal, 1883). The defended border: Upper Canada and the War of 1812 . . . , ed. Morris Zaslow and W. B. Turner (Toronto, 1964). Lucien Gagné, Salaberry, 1778–1829 (thèse de phd, univ. de Montréal, 1948). George Gale, Historic tales of old Quebec (Quebec, 1923). Mollie Gillen, The prince and his lady: the love story of the Duke of Kent and Madame de St Laurent (London, 1970; repr. Halifax, 1985). G. R. Gleig, A sketch of the military history of Great Britain (London, 1845). Michelle Guitard, Histoire sociale des miliciens de la bataille de la Châteauguay (Ottawa, 1983). J. T. Headley, The second war with England (New York, 1853). Hitsman, Incredible War of 1812. Reginald Horsman, The causes of the War of 1812 (New York, 1972); The War of 1812 (London, 1969). J. R. Jacobs, Tarnished warrior, Major-General James Wilkinson (New York, 1938). W. D. Lighthall, An account of the battle of Chateauguay . . . (Montreal, 1889). R. B. McAfee, History of the late war in the western country . . . (Lexington, Ky., 1816). A. T. Mahan, Sea power in its relations to the War of 1812 (2v., London, 1905). J. K. Mahon, The War of 1812 (Gainesville, Fla., 1972). Theodore Roosevelt, The naval war of 1812, or the history of the United States Navy during the last war with Great Britain, to which is appended an account of the battle of New Orleans (New York and London, 1882). Robert Rumilly, Papineau et son temps (2v., Montréal, 1977). Robert Sellar, The U.S. campaign of 1813 to capture Montreal; Crysler, the decisive battle of the War of 1812 (Huntingdon, Que., 1913). G. A. Steppler, “A duty troublesome beyond measure: logistical considerations in the Canadian War of 1812” (ma thesis, McGill Univ., Montreal, 1974). Benjamin Sulte, La bataille de Châteauguay (Québec, 1899). Wallot, Un Québec qui bougeait. J. R. Western, The English militia in the eighteenth century; the history of a political issue, 1660–1802 (London and Toronto, 1965). Samuel White, History of the American troops, during the late war . . . (Baltimore, Md., 1830). W. C. H. Wood, The war with the United States; a chronicle of 1812 (Toronto, 1915). C.-M. Boissonnault, “Le Québec et la guerre de 1812,” Rev. de l’univ. Laval (Québec), 5 (1950–51): 611–25. W. H. Goodman, “The origins of the War of 1812: a survey of changing interpretations,” Mississippi Valley Hist. Rev. ([Cedar Rapids, Iowa]), 28 (1941–42): 171–86. Eric Jarvis, “Military land granting in Upper Canada following the War of 1812,” OH, 67 (1975): 121–34. R. J. Koke, “The Britons who fought on the Canadian frontier; uniforms of the War of 1812,” N.Y. Hist. Soc., Quarterly (New York), 45 (1961): 141–94. G. F. G. Stanley, “The Indians in the War of 1812,” CHR, 31 (1950): 145–65.

Cite This Article

Michelle Guitard, “IRUMBERRY DE SALABERRY, CHARLES-MICHEL D’,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 6, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed January 1, 2026, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/irumberry_de_salaberry_charles_michel_d_6E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/irumberry_de_salaberry_charles_michel_d_6E.html |

| Author of Article: | Michelle Guitard |

| Title of Article: | IRUMBERRY DE SALABERRY, CHARLES-MICHEL D’ |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 6 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1987 |

| Year of revision: | 1987 |

| Access Date: | January 1, 2026 |