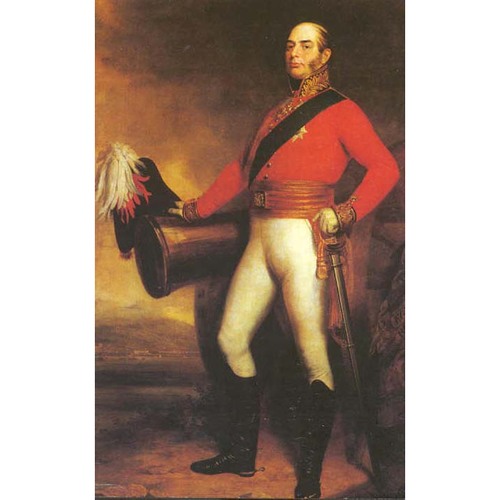

Source: Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

EDWARD AUGUSTUS, Duke of KENT and STRATHEARN, army officer; b. 2 Nov. 1767 at Buckingham Palace, London, England, fourth son of George III, King of Great Britain and Ireland, and Charlotte Sophia of Mecklenburg-Strelitz; d. 23 Jan. 1820 in Sidmouth, England.

At a very early stage Edward Augustus lost the favour of his father, and he never regained it. The king, disliking him strongly, was for many years determined to keep him out of England. Destined for the army like several of his brothers, he received his secondary and military education in Hanover and Lüneburg (Federal Republic of Germany) and at Geneva (Switzerland), where he was desperately unhappy and began to contract the debts which were to plague him all his life. He also had bad luck, best exemplified by the loss at sea on seven occasions of expensive sets of military dress and equipage. On 30 May 1786 he was gazetted colonel, and then in April 1789 received the colonelcy of the 7th Foot. When he returned to London from Geneva the following year without leave, his father immediately sent him to take command of his regiment at Gibraltar. It soon became evident that the prince was a strict disciplinarian even by the standards of the age and that he was passionately concerned with the minute points of military dress and decorum. In 1791 the 7th, which was chafing under Edward’s command, was ordered to Quebec. As a prince of the blood Edward naturally entered the highest social circles there, and he was especially friendly with leading Canadian families. With Ignace-Michel-Louis-Antoine d’Irumberry* de Salaberry he maintained a correspondence for the rest of his life and he took a lively interest in the military careers of Salaberry’s three sons, including Édouard-Alphonse and Charles-Michel*. In 1792 he paid a brief visit to Lieutenant Governor Simcoe at Newark (Niagara-on-the-Lake), Upper Canada.

On the outbreak of war with France in 1793 Edward (who was promoted major-general on 2 October) eagerly volunteered for service, and he served as a brigade commander at the reduction of Martinique and St Lucia in 1794. He then went to Halifax, N.S., where he was appointed commander of the forces in Nova Scotia and New Brunswick. The prince took a stern view of drunkenness and gambling and even, according to contemporaries, made an inexorable stand against what he considered the loose morals of society at large. It was his custom to parade the Halifax garrison every morning at five and to attend in person. The continuing severity of his punishments for breaches of military conduct made him unpopular. At the same time, however, his actions were punctuated by conspicuous acts of humanity to the troops.

In view of the war with France, Edward embarked on an ambitious program of reconstruction of the Halifax fortifications, which had fallen into considerable disrepair after the American revolution. A new citadel was built to replace the old one, and Citadel Hill itself was cut down to accommodate the new works. Other batteries and fortifications including several towers were also erected, and a boom was placed across the Northwest Arm to prevent an enemy fleet from entering and bombarding the town from the rear. One innovation was the creation of a signalling system to facilitate communications between Halifax and the outposts. Although these works were built at a cost much higher than the original estimates, only a decade later many were in virtual ruins.

The prince injured his leg by a fall from his horse in 1798, and when his doctors (including William James Almon and John Halliburton) suggested convalescence in England he eagerly took up the idea and left Halifax in October. In March 1799 parliament granted him an annual income of £12,000, and the next month he was created Duke of Kent and Strathearn; promotions to general and as commander-in-chief of the forces in British North America followed in May. Edward returned to Halifax in September 1799, but ill health cut short his stay and he left again in August 1800. This sojourn completed his North American experience: his ambition to become governor-in-chief of British North America was never realized. Except for a brief and unfortunate second term at Gibraltar from May 1802 to the spring of 1803, when he was recalled because of rumours of harsh discipline, his active military career was finished. He was promoted field-marshal by seniority in September 1805. Though somewhat protected by his older brothers from his father’s strong adverse prejudices, he was unable to obtain important office, and most of the remainder of his life was spent in retirement on his estate at Ealing (London). He became president or benefactor of a great many charitable societies, and was much interested in the socialist doctrines of Robert Owen. For pecuniary reasons he resided at Brussels (Belgium) from 1815 to 1818.

Prince Edward is remembered in Halifax for initiating plans for the construction of the clock tower at the foot of Citadel Hill (although it was not begun until after his departure), for his contribution to the building of St George’s Round Church, for his active interest in helping Nova Scotians he had known while there, and for his residence on Bedford Basin at Prince’s Lodge which he leased from Lieutenant Governor John Wentworth, with whom he maintained close and friendly relations. There he lived with Thérèse-Bernardine Mongenet*, known as Mme de Saint-Laurent. She had come to Gibraltar in 1790 at his request and followed him faithfully on his travels to Quebec, Halifax, Ealing, and finally to Brussels where they parted. There can be no doubt that he was remarkably devoted to this companion who shared fully in his life. In 1818, after 27 years with Julie, as she was better known, the danger of failure in the royal succession obliged him to respond to public and family pressure for his marriage. He made a generous financial settlement upon Mme de Saint-Laurent, and on 29 May 1818 at Coburg (Federal Republic of Germany) married Victoria Mary Louisa, widow of the prince of Leiningen. The birth of Princess Victoria, the future queen, one year later was the result wished for by public opinion. The duke was proud of her, and he and the duchess paraded the baby at every opportunity. In December 1819 he took his family to a country house in Devon, where he died of pneumonia a month later.

Much about Edward Augustus’s life is still unknown. Rumour spoke of children by Mme de Saint-Laurent and others, stories which Queen Victoria much disliked and endeavoured to suppress, and Sir William Fenwick Williams* took pleasure in not denying that he was the duke’s son.

The later correspondence of George III, ed. Arthur Aspinall (5v., Cambridge, Eng., 1962–70). The life of F.M., H.R.H. Edward, Duke of Kent, illustrated by his correspondence with the De Salaberry family, never before published, extending from 1791 to 1814, ed. W. J. Anderson (Ottawa and Toronto, 1870). Royal Gazette and the Nova-Scotia Advertiser, 1794–1800. DNB. G.B., WO, Army list, 1786–1820. David Duff, Edward of Kent: the life story of Queen Victoria’s father (London, 1938; repr. 1973). Mollie Gillen, The prince and his lady: the love story of the Duke of Kent and Madame de St. Laurent (Toronto, 1971). Erskine Neale, The life of Field-Marshall His Royal Highness, Edward, Duke of Kent, with extracts from his correspondence, and original letters never before published (London, 1850). Harry Piers, The evolution of the Halifax fortress, 1749–1928, ed. G. M. Self et al. (Halifax, 1947).

Cite This Article

In collaboration with W. S. MacNutt, “EDWARD AUGUSTUS, Duke of KENT and STRATHEARN,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 5, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed December 14, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/edward_augustus_5E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/edward_augustus_5E.html |

| Author of Article: | In collaboration with W. S. MacNutt |

| Title of Article: | EDWARD AUGUSTUS, Duke of KENT and STRATHEARN |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 5 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1983 |

| Year of revision: | 1983 |

| Access Date: | December 14, 2025 |