Source: Link

CARLETON, THOMAS, army officer and colonial administrator; b. c. 1735 in Ireland, youngest son of Christopher Carleton and Catherine Ball; m. 2 May 1783 Hannah Foy, née Van Horn, in London, England; d. 2 Feb. 1817 in Ramsgate, England.

Thomas Carleton’s career and achievements have been overshadowed by the better-known exploits of his elder brother Guy, Lord Dorchester, and by the plans and actions of the New Brunswick loyalist élite with whom Thomas worked closely in founding and shaping a new colony. His cryptic style and sporadic letter-writing habits – “I’m so seldom guilty of the crime of writing long ones,” he acknowledged to his patron, Lord Shelburne – have handicapped historians attempting to study the man. Even the public Carleton may not be accurately displayed since, with Jonathan Odell functioning as his provincial secretary and Edward Winslow as his military secretary, he possibly appears, in William Odber Raymond*’s words, “to much greater advantage in his official correspondence than he would otherwise have done.”

In 1753, after a childhood in Ireland, Thomas joined the 20th Foot as a volunteer. He quickly rose in rank, becoming a lieutenant and adjutant by early 1756, and saw considerable service in Europe during the Seven Years’ War. On 27 Aug. 1759 he was promoted captain. Posted with his regiment to Gibraltar following the peace in 1763, Carleton was restless and in 1766 appealed to Shelburne, “as my only resource,” that in the event of another war his patron (then secretary of state for the Southern Department) would not “suffer me to be shut up with a set of Gourmands in this horrid Prison.” During a ten-month leave of absence he visited Minorca, Algiers, and different parts of France and Italy, eventually rejoining his regiment and returning to England in 1769. Appointed major on 23 July 1772, he again took leave to tour in Europe. No doubt it was because he was a well-travelled man of the world that Shelburne recommended him to accompany Lord John Pitt, eldest son of the Earl of Chatham, to Canada. But in March 1774 Thomas postponed the trip in favour of more adventurous service with the Russian army, then battling “with the Turks on ye Lower Danube.” After visiting Constantinople (Istanbul) and wintering in St Petersburg, he returned to England in 1775.

In August 1775 Guy Carleton, governor of Quebec, recommended that his brother be made quartermaster general to the forces there, and the following year, now with a lieutenant-colonelcy in the 29th Foot, Thomas took up the appointment. As the American Revolutionary War progressed he became, like his brother, increasingly critical of the ministry’s handling of the military effort. In fact, his censure was so intense that at one point he sarcastically commented, “This letter contains the worst kind of Treason against the Minister so I shant put my name to it.” Towards the end of the war he watched with interest the fluctuating fortunes of Shelburne and wondered whether a return to England might be in order: “One risques being estranged to their Friends if not forgot by them, from long absence. . . .” By June 1782, however, a “happy change of administration” had placed Shelburne in his “proper sphere,” and Thomas looked forward to joining his brother, now Sir Guy, at New York City and eventually to receiving another Canadian appointment.

Before leaving for New York he had a number of problems to iron out with his commanding officer, Frederick Haldimand. The two had clashed several times, with the ever prickly Carleton feeling that he was treated as “a Cypher” and his rank not respected. A final confrontation occurred when Haldimand demanded that he resign his position as quartermaster general before his departure. This Carleton refused to do until he had received another appointment, and he left Quebec without the matter having been resolved. After a brief stop at New York, where he found no position vacant, Carleton journeyed to England. There, in the shelter of Shelburne’s country estate, he wrote to Haldimand arguing that his rather abrupt leave-taking had been justified by the need to explain in England the expenditures of his quartermaster’s department. Evidently unconvinced, Haldimand removed Carleton’s name from his staff list, appointing Colonel Henry Hope* in his place. With his military record tarnished and his career threatened, Carleton was not helped when, after February 1783, Shelburne (by then prime minister) was rendered powerless as the leadership of his party passed to William Pitt. Not surprisingly, when an appointment as governor of the newly created colony of New Brunswick was offered in the summer of 1784, Thomas accepted it.

He had not, however, been in a completely helpless position. The Carleton name was still respected and Sir Guy was under consideration for the post of governor in chief of British North America. In addition, finding a governor for New Brunswick had proved no simple task: both General Henry Edward Fox and Colonel Thomas Musgrave had already declined the office. Indeed, Thomas had had a strong enough bargaining position to get a commitment from the ministry that his New Brunswick service would be temporary, to be followed by the lieutenant governorship of Quebec. Later, however, he was to consider his appointment “one of the most fortunate events of my life,” and he had accepted it none too soon as it turned out. Haldimand sailed to England in the fall of 1784, and the next year Carleton expressed his “uneasiness” over the apparent decline of his reputation with the Home secretary, Lord Sydney. As he wrote to Shelburne, “If I had persisted in refusing this Government [the government of New Brunswick], the hostility of a Minister might have been fatal, now . . . altho formidable it may be withstood.”

Carleton’s concern about possible attacks from Haldimand and Sydney revealed his insecurity, an insecurity no doubt heightened by the fact that others, both above and below him, had clearer ideas about the form the new colony should take. During the campaign for the partition of Nova Scotia in 1783–84 members of the aspiring loyalist élite, such as Winslow and Ward Chipman*, were active and articulate, and Sir Guy, who was “warm for the new Government,” also had considerable influence. Thomas, on the other hand, seems not to have played a significant role. He apparently had no voice in the appointment of the first New Brunswick council (not surprisingly, perhaps, given the crush of office seekers waiting to be rewarded), while the occupant of at least one other post, and probably more, “was fixed upon by Col. Carleton at the recommendation of his Brother.” Carleton was no doubt consoled by his colonel’s rank (awarded on 20 Nov. 1782), a War Office commitment that two regular regiments would be stationed in New Brunswick, and the understanding that his appointment would be temporary. After taking the oaths of office on 28 July 1784, he sailed in early September for Halifax, N.S., accompanied by his wife as well as by Odell, Chipman, Gabriel George Ludlow, and other newly appointed office holders.

In late November, after stopping briefly in Halifax, Carleton and his entourage reached Parrtown (Saint John), which became the governor’s temporary capital. Although clearly instructed to call an assembly as soon as possible, Carleton decided “to finish every thing respecting the organization of the Province that properly belonged to the prerogative before a meeting of Representatives chosen by the people.” Hence New Brunswick was to be governed in its first year by Carleton and the Council, a body composed largely of loyalists which consistently offered “unanimous advice.” This close cooperation between the governor and the loyalist élite profoundly influenced the shape of the new colony. Indeed, Carleton’s conception of a proper colonial society was not greatly different from theirs. Like his brother, he was the product of an Anglo-Irish milieu, where the need for a ruling class, an established church, and a controlled parliament were accepted, and his views, modified by his military interests, matched the hopes of the loyalists for “a stable, rural society governed by an able tightly knit oligarchy of Loyalist gentry.”

By the time of Carleton’s arrival the indifference of Governor John Parr* of Nova Scotia to the new settlements of loyalists and soldiers on the Saint John River had combined with the winter chill and insufficient provisions to slow colonial development. Moreover, Guy Carleton’s thoughts concerning a march to the north to open new land on the upper Saint John and the consolidation of existing settlements seemed on the point of abandonment. Drawing upon his elder brother’s suggestions, his own inclinations, and the aspirations of the élite, Thomas moved quickly and enthusiastically to revitalize the faltering colony. Prior to the calling of an assembly, there was a whirlwind of significant measures. Because of its central location, St Anne’s Point, renamed Fredericton, was “fixed on” as the new capital, a chief justice, assistant judges, and an attorney general were appointed, counties and parishes were created, and a charter of incorporation was issued for Saint John. It was strongly asserted as well that of the three rivers known by the name St Croix, the one commonly called the Scoodic should form the western boundary of New Brunswick. The most pressing needs of the recently arrived loyalists were also dealt with. Applications for grants were processed and land registered or in some cases escheated. Carleton also arranged that the period during which the refugees were to receive free provisions be extended to May 1787 and that, if necessary, they be allowed to use American boats, rather than rely on “British bottoms,” to transport their possessions to New Brunswick. The assignment of loyalists to land already occupied by pre-loyalist settlers, both Acadian and English, created a problem which Carleton and the Council resolved by ordering the new claimants to pay compensation to “the occupants for their Improvements.” Arrangements were made in the case of the Acadians for their resettlement in other parts of the colony.

By the end of 1785 the main lines of New Brunswick’s future development had been established. It was to be a well-governed outpost of the empire, with settlement patterns dictated by what Carleton considered to be the colony’s military needs, and blessed with a deferential, well-ordered society; it was to be a loyalist “asylum” that would eventually be the “envy of the American States,” a society quite unlike that taking shape in post-revolutionary America. The affinity, both in thought and in action, between the governor and his loyalist advisers makes it difficult to disentangle their perceptions and desires. Carleton clearly had appropriated many loyalist beliefs; yet the élite was at times equally receptive to and unquestioning about the governor’s dictates. In the matter of appointments, which in the first years went almost exclusively to loyalists, Carleton’s explanation of the qualifications of his nominees revealed his respect for the refugees. “These are Gentlemen,” he wrote, “not only of real merit, but also distinguished by services and sufferings during the late Rebellion . . . .” No doubt Odell, Ludlow, Winslow, Chipman, and others wholeheartedly endorsed his selection of such “Enemies of Faction,” such opponents of “violent party spirit,” and would equally support the constitutional arrangements Carleton hoped to evolve. At the municipal level, although the charter for Saint John granted a certain amount of democracy to the electorate, Carleton was at pains to point out that “there is a sufficient influence retained in the hands of Government,” through the governor’s direct appointment of mayor, sheriff, recorder, and clerk, “for the preservation of order and securing a perfect obedience.” At the provincial level, Carleton bluntly stated, “It will be best that the American Spirit of innovation should not be nursed among the Loyal Refugees by the introduction of Acts of the Legislature, for purposes to which by the Common Law and the practice of the best regulated Colonies, the Crown alone is acknowledged to be competent.” The vigilant exercise of the crown’s rights was to be accompanied by the “strengthening [of] the executive powers of Government [to] discountenance its leaning so much on the popular part of the Constitution.”

Such views and actions soon came under fire both from within New Brunswick and from London. In early November 1785 the first provincial election turned into a turbulent affair when troops had to be sent to quell a riot in Saint John. The contest, as William Stewart MacNutt* describes it, was “government men against those who had not been admitted to privilege” [see Elias Hardy*]. Fines and jail terms were eventually meted out and the six disputed seats in Saint John were awarded to the Jonathan Bliss*–Ward Chipman group, the governor’s friends. To Carleton it was a lesson “to hold the Reins of Government with a strait hand, and to punish the refractory with firmness,” and also demonstrated the need for more military forces to be stationed in the area. After receiving Carleton’s report on the election Sydney approved the way the governor had dealt with the “intemperate behaviour of Mr. Hardy” and his followers, but on other matters he was far from happy with Carleton’s performance. Questions had been raised about the governor’s delay in forwarding to London the fee schedule he and the Council had established and also about his hesitation in calling an assembly. What had most disturbed Sydney were the legal problems created by the hasty incorporation of Saint John, since “no Authority is given in Your Commission for granting Charters of Incorporation.” At the same time Carleton was involved in a wrangle with Major-General John Campbell, commander of the troops in eastern Canada, concerning Carleton’s jurisdiction over the troops in New Brunswick, only one regiment of which had as yet arrived.

Thomas’s position strengthened considerably with the appointment of his brother, soon to be Lord Dorchester, as governor-in-chief in early 1786 (at which time Thomas received a new commission as lieutenant governor). Sydney made it clear that military problems would be resolved by the elder Carleton, and no doubt Thomas would benefit over the aggrieved Campbell. Even before receiving word of this favourable turn of events Thomas had shown himself willing to challenge Sydney’s criticisms. He defended the legitimacy of all his actions and, elaborating upon his successes, he assured the Home secretary “that faction is at an end here.” In truth, Carleton and his loyalist allies were very much the masters of New Brunswick. The first assembly met in January 1786 to, as Carleton phrased it, “put the finishing hand to the arduous task of organizing the Province.” Opposition disappeared, with the assembly demonstrating a total willingness to cooperate. By 1788 the shift of the seat of government to Fredericton had been completed and the assembly held its first meeting there in July. The absence of controversy moved Carleton to comment in opening the 1789 session that “by provident attention, in former Sessions, to the various exigencies of this infant colony, the business I have at present to recommend to your deliberation, is reduced to little more than a renewal of temporary laws. . . .”

Thomas’s cause and career by now were closely bound up with the fortunes of his brother and of his own allies in the colony, the loyalist leaders. To some observers, Thomas was a virtual puppet of the governor general. In reality, while Thomas welcomed Dorchester’s appointment and in 1788 risked a hazardous winter journey of 350 miles on foot to be at his sick brother’s side, there were issues over which the two men disagreed. The New Brunswick–Quebec boundary provides one example, with Thomas successfully defending the Madawaska region as part of his colony. None the less, Carleton’s fate was linked with his brother’s, and in the late 1780s enemies were sniping. Haldimand in England continued his caustic comments about Thomas, “who certainly does not deserve favours,” while Parr in Nova Scotia freely lampooned both brothers in his private correspondence. The latter’s remarks were particularly embarrassing to Thomas because they were addressed to Shelburne. But, although aware of Parr’s hostility, Thomas never successfully countered his insinuations. Parr’s willingness to criticize the Carletons without any apparent fear of offending Shelburne perhaps explains why Thomas’s connection with this once concerned patron withered away by the end of the 1780s.

Even more damaging to Thomas Carleton were suggestions of misrule and incompetence within New Brunswick. Although he was cautiously optimistic about the colony’s potential, particularly in agriculture, which he believed must take precedence over trade, his assessment of progress in the first few years was balanced and realistic. In a report to Dorchester in 1787 he openly recognized some of the economic setbacks experienced in the colony and indirectly acknowledged the slowness of its overall development. He stopped short, however, of attaching blame. Others were not so hesitant about who was at fault. “This Province would by this time have had thrice the Number of Inhabitants it now has, had not its Government been inimical to its Settlement,” wrote James Glenie in November 1789. Glenie was to be a perennial thorn in the side of the administration and, at times, his comments were exaggerated and unfair. In this instance he had received a power of attorney to act for Andrew Finucane in the struggle to regain title to Sugar Island, which the government had allowed disbanded soldiers to settle. Glenie perceived a conspiracy to deprive Finucane of his property and Carleton was implicated: “The Govr. is to have his share in Consequence of a joint Purchase which he and Judge [Isaac Allan] have made in the Neighbourhood of the Island.” A lieutenant governor and a clique enriching and protecting themselves by means of the offices they enjoyed were allegedly thwarting the colony’s development. Regardless of the validity of Glenie’s charges, they were serious accusations, and many more would be heard by officials at home in the years ahead. Finucane having complained to London about his treatment, in September 1789 Carleton had been forced to offer a detailed explanation of the process by which the family had lost its rights to Sugar Island. On the surface it looked as if due process of law had been scrupulously observed, but the seeds of suspicion had been planted.

Suggestions of misrule, an apparent loss of support from Shelburne, a colony developing slowly, all these had severely complicated and possibly compromised Carleton’s career. His original hope, of serving only briefly in New Brunswick, had virtually vanished by 1790. Admittedly, the manner in which his removal was postponed gave the impression that satisfaction with his performance was the cause. The lieutenant governorship of Quebec had been offered to him in 1786. “At the same time,” wrote Lord Sydney with reference to New Brunswick, “I should not fulfill his Majesty’s Commands, were I not to acquaint you . . . [that] His Majesty is persuaded that His Service would receive considerable benefit by your continuance in that Province.” While Carleton loyally expressed a willingness to carry on, he privately confided that “if my staying in the Province is thought of consequence My Lord Sydney should have tempted me with something more solid than empty words.” A year later more was offered with the news that on Campbell’s departure he was to be made brigadier-general in America and given command of the troops in New Brunswick. But his 1788 visit to Quebec reminded Carleton of the way he was being passed over while others moved ahead. His complaints brought soothing reassurances from England that the king intended to reward his services “as soon as a favourable opportunity shall present itself.” Nevertheless, although he was consulted when the Quebec lieutenant governorship came open again in 1789, the same argument against his removal was offered. What could Carleton do but “express my perfect acquiescence in His Majesty’s desire that I should remain at New Brunswick.”

Carleton was above all else a military man and it would have been easy for him to concentrate on this career, neglecting his civil responsibilities, once the prospect of further colonial appointments dimmed. To his credit, he continued to speak out concerning New Brunswick’s needs in other areas. Threats to change or set the northern, western, and southern boundaries to the colony’s disadvantage were effectively challenged throughout his lieutenant governorship. The news that parliament had approved a grant for the creation of a college in Nova Scotia prompted Carleton to request the same funding for a “public Seminary of learning” in New Brunswick. Although the home government refused its support and the colony had to be content with a grammar school in Fredericton, the assembly cooperated in granting land and limited funding and the first steps had been taken towards the creation of the College (eventually the University) of New Brunswick. What Carleton was powerless to change, however, was the colony’s economic decline. His report in 1791 that the importation of provisions from the United States was continuing and that lumber had been added to the list of permitted imports graphically revealed its predicament. British restrictions on further land grants within the colony, imposed in 1790 in the hope that crown lands could be sold, were a major set-back; at the same time land values fell, grain- and sawmills went idle, immigration ceased, and the debts of even the élite mounted. Imperial indifference was capped in 1794 when American vessels were again given access to the West Indies trade, a decision that destroyed New Brunswick’s “ocean-going commerce” and reinforced agricultural underdevelopment.

Some compensation, from Carleton’s point of view, was provided by the emergence of the province, at least temporarily, as the military bastion he had originally envisioned. In 1788 he had argued that more military posts were needed to protect the line of communication with Quebec and “to encourage settlements in their neighbourhood,” and in 1790, with the arrival of the second of the two regiments promised the colony, the line of outposts stretching northward could be achieved. Garrisons were already being maintained at Saint John and Fort Cumberland (near Sackville); under Dugald Campbell new posts were now established at Grand Falls and Presque Isle. Carleton was also able to station “a respectable Corps at Fredericton, which I conceive to be an object of great importance; The situation is centrical and peculiarly advantageous for the Troops.” Questions were raised immediately about the concentration of manpower and ordnance stores at Fredericton rather than in Saint John. Eventually Carleton was overruled by the War Office and forced to accept the greater military importance of Saint John. For a brief moment, however, he was in his element with paymasters, barrack-masters, and town majors in Fredericton, along with an entire regiment doing nothing according to Glenie but “mounting guard on the Governor’s Farm.” Then in late 1792 an upset and protesting Carleton received orders to transfer one regiment to Halifax, and the following February the second was dispatched to the West Indies. Replacing the regulars was “a Corps not exceeding 600 Men” to be raised by Carleton within the colony and commanded by him “but without any Pay in consequence thereof.” No doubt softening the blow was the major-general’s rank he received in the regular army on 12 Oct. 1793, as well as an appointment as colonel commandant of a battalion of the 60th Foot in August 1794. War with France had precipitated these decisions and, again to his credit, Carleton responded as a loyal soldier and governor. While encouraging recruitment for the new corps, the King’s New Brunswick Regiment, Carleton also rushed through a new militia bill, strengthened Saint John’s defences, and made a personal contribution of £500 to a fund for the defence of Britain. Loyalty must have been mixed with bitter disappointment, nevertheless, when Prince Edward Augustus was welcomed to the colony in 1794. The prince assumed command of all troops in New Brunswick and Nova Scotia, eclipsing Carleton and, with his base in Nova Scotia, guaranteeing that Thomas’s colony would never be the heart of the British defences in eastern Canada.

At the same time the lines were being drawn within New Brunswick for a confrontation between the lieutenant governor and Council and the elected assembly, a battle that disrupted the colony for a considerable time and finally soured Carleton on New Brunswick. James Glenie would have a major role, although the sincerity of his championing of assembly rights is questionable. The lieutenant governor, Glenie claimed, had been placed by his friends “in a Situation which nature never intended him for, and for which he is by no means qualified by Education, Capacity or Experience”; he was, moreover, to blame for New Brunswick’s failure to prosper, being “by Constitution an Enemy to Business and by practice an utter stranger to it.” These attacks on the lieutenant governor have been assessed by the historian George Francis Gilman Stanley as of “little weight in London.” Yet some of the charges were presented to Home Secretary Henry Dundas, no friend of the Carleton family. When Carleton complained in 1792 of Council positions being awarded without his “concurrence,” and his authority being thus undermined, Dundas was quick to lecture him on “an unbecoming doubt of the wisdom and discretion of His Majesty’s Councils.” In the major confrontation between executive and assembly, however, Carleton at least had some support from the Duke of Portland, who succeeded Dundas.

The election of 1793 replaced a cooperative assembly with one far more critical and assertive, and Carleton found some of his recommendations ignored. The simmering discontent reached a peak in 1795. Defence expenditures by the lieutenant governor in Saint John and St Andrews were rejected by the assembly and, in retaliation, the appropriation bill, which provided for salaries for assembly members, was rejected by the Council, as was a proposal to have the Supreme Court sit in Saint John as well as in Fredericton. This agitation was typified by Glenie’s bill, “Declaratory of what Acts of Parliament are Binding in this Province,” again a measure passed by the assembly and vetoed by the Council. Dissolution of the assembly in August 1795 and the election of new legislators provided no relief for Carleton and the Council; the deadlock remained and government ground to a halt from 1795 to 1799. Much of the assembly’s restlessness, in Carleton’s opinion, was due to the Fredericton emphasis of his government, since the “mercantile Interest” of Saint John, Charlotte, and Westmorland counties still hoped that the seat of government might be moved to Saint John. He saw in this attempt to undermine his master-plan a conspiracy of “a few Members, who evidently have a predilection for the Republican Systems formerly prevalent in the chartered Colonies of New England.” Portland attempted throughout to rule on each of the thorny issues being debated, usually expressing a cautious approval of the position taken by Carleton and the Council. As the dispute dragged on, however, an increasing exasperation with “idle and groundless differences” emerged in his correspondence.

Even New Brunswick grew weary of the conflict. A more conciliatory mood was produced in the assembly when Carleton manipulated evidence of the home authorities’ displeasure, on one occasion carefully selecting passages from Portland’s letters for the information of Amos Botsford, speaker of the house. The opposition cause was further weakened when, in the 1797 session, Glenie dared to introduce a censure motion against the lieutenant governor himself. With the exception of Stair Agnew* and three others, the assembly drew back at this direct attack on the king’s representative. Still it was not until the 1799 session, when Carleton laid before the house extensive extracts from Portland’s correspondence outlining “the principles and rules of legislative proceeding,” that the deadlock was broken. Both sides compromised: the assemblymen separated provision for their salaries from the appropriations fox other services; the Council waived its opposition “to some irregularities in the bills of this Session” and passed supply bills for the preceding four years. Though the further adjustments that marked the 1799 and 1801 sessions seemed to vindicate the executive (the assembly, for example, tolerated Council review of appropriation items before inclusion in the final bill), in fact a fundamental shift in power was under way. At the heart of the struggle, Botsford believed, had been the assembly’s “inherent and indubitable privileges,” whose vigilant protection and development were totally compatible with “the well tried loyalty of those, who compose the House of Assembly”: “they had not acted from a spirit of opposition or obstinacy or want of parliamentary information . . . they had sacrificed no essential rights, and only altered the mode in granting, from a desire of harmony and in conformity to the sentiments and the clear light thrown on the subject by his Grace’s important communications.” In reality, New Brunswick was witnessing the emergence of the assembly’s “political hegemony” as power passed to the elective branch of government.

This erosion of executive power ran contrary to Carleton’s philosophy of government and, when linked with the almost total erosion of his military authority, convinced him of the need to remove himself from New Brunswick. By 1800 he was quite frank about the slow economic development of the colony, blaming short-sighted imperial policies for this failure. The now ten-year-old restriction on land grants was a particularly sore point. Some satisfaction had been achieved in 1798 with the temporary resolution of boundary problems with the United States, the Scoodic River being confirmed as the western boundary of New Brunswick [see Thomas Wright], and in 1800 Carleton’s continuing encouragement of “the Infant College” culminated in a provincial charter of incorporation. But in the military sphere, his pride and authority received a series of blows. Despite his strenuous opposition, his right to appoint the town major and barrack-master in Fredericton was lost in 1796 and the deputy paymaster’s office was removed from his patronage in 1798. Halifax’s position as the military centre of British defences was confirmed in September 1799 when Edward Augustus, now Duke of Kent and Strathearn, assumed command of the forces in British North America with headquarters in the Nova Scotia capital. Shortly afterwards, arguing that these changes had altered “the nature of the charge I have been honoured with” and reduced him to “a public Accountant,” an embittered Carleton asked permission to resign.

While Portland expressed surprise and regret, he promised to act on the request. On the other hand, the Duke of Kent seemed honestly concerned at the possible loss. Informed by the duke that the service of the New Brunswick Regiment was to be extended and that it might be “shortly placed on the establishment of Fencibles,” Carleton began to reconsider. He now believed his resignation had been premature, and rather tactless, and, employing the change in status of the New Brunswick Regiment as an excuse, he begged Portland “to bury in oblivion” his resignation. Portland complied and Carleton continued in office. There were better ways to leave New Brunswick than an abrupt resignation after a harsh censure of the ministry and Carleton would seek them. In the interval, perhaps he could enjoy the political lull and his remaining military responsibilities.

It was to be a short interval. The legislature had not met since February 1799, but when it reconvened in January 1801 Robert Pagan* introduced a motion censuring Carleton for expending funds on the legislative building at Fredericton without the approval of the legislature. It did not pass, but served as a painful reminder of the continuing close scrutiny of executive actions. The following year a squabble broke out over who should be appointed as clerk of the assembly, the house favouring Samuel Denny Street* while the Council and Carleton wanted, and appointed by letters patent, Dugald Campbell. Obsessed with what he perceived to be emulation of unacceptable American practices, Carleton saw in assembly appointment of the clerk “one of those usages of the late New England Provinces.” Contention and disappointment also marred Carleton’s military service. Citing weather conditions, expense, and lack of military manpower, he opposed one of the Duke of Kent’s pet projects, a primitive telegraph system stretching from Saint John to Fredericton and eventually from Halifax to Quebec. Meanwhile the New Brunswick Regiment was ordered disbanded. In June 1802, capitalizing upon the peace between France and England, Carleton requested a leave of absence to attend to his private affairs and the request was granted. Early in October 1803, accompanied by his wife, son William, daughters Emma and Anne, and stepson Captain Nathaniel Foy, he sailed for England, never to return to New Brunswick. The direction of the colony was left to Gabriel George Ludlow, the first of a series of administrators who were to govern in Carleton’s absence over the next 13 years.

Once home, Carleton did not immediately forget his responsibilities as lieutenant governor. Indeed, the generally accepted theory that he had little interest or involvement in civil matters, leaving these to his loyalist advisers as Edward Winslow hinted and a number of historians have asserted, is contradicted by the evidence. Though concerned about “the little prospect of being able to draw the attention of Ministers towards our part of the world,” and handicapped of course by the lack of any extensive correspondence except with Winslow, he kept a watchful eye on activities in New Brunswick and did not hesitate to speak out. Among his concerns were the salary arrears of Society for the Propagation of the Gospel workers in New Brunswick, the colony’s desire to issue paper currency, and changes in legislation dealing with the import and sale of goods. He continued to oppose as futile the attempt to collect quitrents, imposed when the restriction on land grants was lifted in 1802, and advocated an increase in the “slender salary” of the New Brunswick Supreme Court judges [see Joshua Upham]. Testaments to the loyalty and ability of some who had served under him were penned, but the interests of his friends were more directly served by his quick nomination of replacements when vacancies occurred on the Council or in the judiciary. Ironically, a controversy over one such vacancy completely alienated a once loyal supporter and convinced Carleton of his impotence within ministerial circles. In 1806 he nominated Ward Chipman for a judgeship on the Supreme Court, arguing that Edward Winslow’s talents “would not atone for the want of Law knowledge.” The ministry nevertheless dared to appoint Winslow, who had acquired important connections in England, and the lieutenant governor was outraged. Shortly thereafter, having learned of Carleton’s opposition, Winslow was urging his patrons “to send us out some active and respectable man for a Governor” in place of Carleton, who continued to collect £750 each year while residing “for his amusement . . . at Ramsgate in England.”

The affront to Carleton, as Edward Goldstone Lutwyche, one of his severest critics, observed, left him “some reason to be displeased.” Chances of his returning to New Brunswick, a prospect he had several times considered, now were reduced considerably. By this time as well, residence at Ramsgate, winter visits to Bath, periods with Lord Dorchester at Stubbings House (near Maidenhead), and sojourns in London had seduced his family. One observer correctly predicted that it would be difficult for the Carletons again to endure life in New Brunswick. But when ordered to return in August 1807, Carleton actually prepared to do so, until he learned that Lieutenant-General Sir James Henry Craig had been appointed governor and commander-in-chief in British North America. As he then bluntly informed Viscount Castlereagh, the secretary for War and the Colonies, “Officers of a superior rank in the King’s Army, cannot with propriety serve under the Command of inferiors . . . a situation of that sort must not only be very painful to such senior officers, but prove greatly injurious to the King’s Service.” An anonymous bureaucrat, obviously flustered by this missive, merely noted on it: “What ought to be done on this?” Carleton had washed his hands of New Brunswick and in the years ahead, despite periodic requests from the colony that a new lieutenant governor be appointed, the home authorities left him alone. His military and civil careers, in effect, had ended but he chose to remain lieutenant governor of New Brunswick until death, on 2 Feb. 1817, removed him. He was buried beside Lord Dorchester in St Swithun’s Church at Nately Scures, near Basingstoke. Only then did the British government appoint a successor, George Stracey Smyth*.

Carleton as man and governor is difficult to assess. Often judgements of him are based on the comments of individuals who were his strongest critics after his departure from the colony. Thus Winslow’s description of him as “costive and guarded,” with an “inactive disposition and constitutional coldness,” or Lutwyche’s comment on “a drone with a sinecure,” are frequently repeated. Worse yet, Glenie’s many accusations have been assumed to be valid and James Hannay* can paint Carleton as “reactionary,” “tyrannical,” “obstinate,” “unpopular,” and “dull-witted,” to cite only a sample of his choicer adjectives. On the other hand, there were those who praised Carleton’s “zeal for the welfare of this Province,” his “exact frugality in the managing that which belongs to the public,” his “integrity, urbanity, and rectitude of conduct [which] have greatly endeared him to every good person in this Province.” The faithful Jonathan Odell was moved to poetry at the mere rumour of Carleton’s return to the colony, concluding his ode: “Carleton returns, rejoicing to impart/Fresh Hope and Joy to every loyal heart.” Carleton was a man who kept his distance, even from those supporters who should have been closest to him. Yet his isolation is neither surprising, in view of his emphasis upon rank and position, nor to be condemned, since in dispensing the limited patronage available he could approach the chore, sometimes to the annoyance of his loyalist advisers, with impartial detachment. He was very much his own man and although, like any officer or official of his day, he recognized the need for support from patrons or relatives, he did not hesitate to oppose his superiors if his own or his colony’s interests were threatened. To be sure, some of the resultant controversies were brought on by his abruptness, tactlessness, incorrect assessment, or even obstinacy on occasion. Yet perhaps among the most attractive qualities of the crusty old soldier were his bluntly straightforward approach when aroused and the honest evaluation of both his own and New Brunswick’s problems. Was he a mere rubber stamp of the loyalist élite? Certainly he responded to much of the advice offered by those around him, but it is hard to accept the picture of him as a totally passive participant in the shaping of New Brunswick. Even if at times he only articulated the ideas of his advisers, he was the unquestioned supervisor who made at least some of their dreams a reality, who explained colonial measures and requested home government support on all the crucial matters. A prickly individual who consistently protested any derogation of his position, he is highly unlikely to have blindly followed the élite’s suggestions or signed any dispatch he did not fully approve.

If his administration failed to make New Brunswick the “envy of the American states,” it was at least partially because both Carleton and his colony were the victims of a changing empire. “The Original connexions and attachments are long since worn out,” wrote Benjamin Marston* in 1790. This was Carleton’s problem after the loss of Shelburne’s support and the decline in influence of his elder brother. This was New Brunswick’s problem when it discovered that it was far from the most valued possession in the empire and that the needs of other colonies, such as the West Indies, took priority. Carleton did not believe that “to reign is worth ambition tho’ in Hell” and, when faced with growing neglect and possible insult, he retired from the fray. His brother is acclaimed as “the Father of British Canada” and Thomas Carleton deserves to be acknowledged as the key figure among the founding fathers of New Brunswick.

[The official correspondence of Thomas Carleton is fairly extensive, and frequently duplicated at various archival institutions in collections that bear different names but consist of essentially the same material. At the PAC the basic collection is MG 11, [CO 188] New Brunswick A, 1–26, while at the PRO the following are worthwhile: CO 188/1–23; CO 189/1–11; CO 190/1–5; CO 191/1–5; and CO 193/1–2. The Thomas Carleton letterbooks at PANB (RG 1, RS330, A1–A8) also contain transcripts from the official correspondence. Carleton’s military career can be followed in collections such as PRO, WO 1/2–14, and BL, Add. mss 21848 (Haldimand papers), both available on microfilm at PAC, and PAC, RG 8, I (C ser.), 15. At the BL the original Haldimand papers were examined and Add. mss 21705, 21708–9, 21714–18, 21720, 21725, and 21728–36 were useful.

Private papers concerning Carleton are sparse. At the PAC the following were used: Thomas Carleton papers (MG 23, D3), Shelburne papers (MG 23, A4, 20–34 (transcripts)), and Chipman papers (MG 23, D1, ser. 1, 1, 6). Available at UNBL is the basic source for this period of New Brunswick’s history, the Winslow family papers (MG H2, 1–17). At the N.B. Museum the Thomas Carleton papers and the Odell family papers contain a small number of interesting items. In England the papers of leading figures who might be linked with Carleton were checked. At the PRO references to the governor are found in the Chatham papers (PRO 30/8, bundle 56); at the BL Carleton material is contained in the Windham papers (Add. mss 37875), Liverpool papers (Add. mss 38345, 38388, and 38393), and Dropmore papers (Add. mss 59230).

The most important printed primary source is Winslow papers (Raymond). Other rewarding sources are Annual reg. (London), 1817; N.B., Legislative Council, Journal [ 1786–1830], vol.1; [Frederick Haldimand], “Private diary of Gen. Haldimand,” PAC Report, 1889: 123–299; “Royal commission to Thomas Carleton” and “Royal instructions to Thomas Carleton,” N.B. Hist. Soc., Coll., 2 (1899–1905), no.6: 394–403 and 404–38 respectively; and G.B., WO, Army list, 1758–1817. Carleton’s marriage is recorded in The register book of marriages belonging to the parish of St George, Hanover Square, in the county of Middlesex, ed. J. H. Chapman and G. J. Armytage (4v., London, 1886–97), 1.

Among the secondary sources, books treating Carleton in New Brunswick are Hannay, Hist. of N.B., vol.1; J. W. Lawrence, Foot-prints; or, incidents in early history of New Brunswick, 1783–1883 (Saint John, 1883); W. S. MacNutt, The founders and their times (Fredericton, 1958) and New Brunswick; and Wright, Loyalists of N.B. The better-known Carleton, Lord Dorchester, is examined in DNB; A. G. Bradley, Lord Dorchester (Toronto, 1907; new ed., Sir Guy Carleton (Lord Dorchester) [1966]); Burt, Old prov. of Quebec (1968); and W. [C. H.] Wood, The father of British Canada; a chronicle of Carleton (Toronto, 1916). An appreciation of the imperial background is provided by H. T. Manning, British colonial government after the American revolution, 1782–1820 (New Haven, Conn., 1933) and John Norris, Shelburne and reform (London, 1963). Useful studies of the loyalists are Carol Berkin, Jonathan Sewall; odyssey of an American loyalist (New York, 1974); Wallace Brown, The good Americans: the loyalists in the American revolution (New York, 1969) and The king’s friends: the composition and motives of the American loyalist claimants (Providence, R.I., 1965); W. H. Nelson, The American tory (Oxford, 1961); and M. B. Norton, The British-Americans: the loyalist exiles in England, 1774–1789 (Boston and Toronto, 1972).

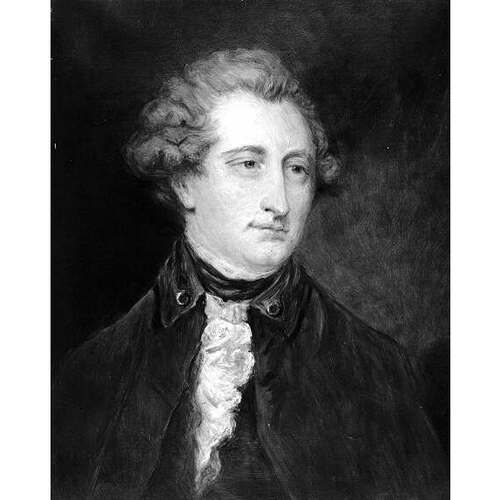

Worthwhile articles dealing with Carleton are W. F. Ganong, “Governor Thomas Carleton,” New Brunswick Magazine (Saint John), 2 (January–June 1899): 72–78; Alec Martin, “The mystery of the Carleton portrait,” Atlantic Advocate (Fredericton), 54 (1963–64), no.4: 28–33; and [W. O.] Raymond, “The first governor of New Brunswick and the Acadians of the River Saint John,” RSC Trans., 3rd ser., 8 (1914), sect.ii: 415–52, and “A sketch of the life and administration of General Thomas Carleton, first governor of New Brunswick,” N.B. Hist. Soc., Coll., 2 (1899–1905), no.6: 439–81. Other helpful articles are T. W. Acheson, “A study in the historical demography of a loyalist county,” SH, no.1 (April 1968): 53–65; A. L. Burt, “Guy Carleton, Lord Dorchester: an estimate,” CHA Report, 1935: 76–87; Marion Gilroy, “The partition of Nova Scotia, 1784,” CHR, 14 (1933): 375–91; W. H. Nelson, “The last hopes of the American loyalists,” CHR, 32 (1951): 22–42; G. [A.] Rawlyk, “The federalist-loyalist alliance in New Brunswick, 1784–1815,” Humanities Assoc. Rev. (Kingston, Ont.), 27 (1976): 142–60; W. O. Raymond, “Elias Hardy, councillor-at-law,” N.B. Hist. Soc., Coll., 4 (1919–28), no.10: 57–66; G. F. G. Stanley, “James Glenie, a study in early colonial radicalism,” N.S. Hist. Soc., Coll., 25 (1942): 145–73; and J. C. Webster, “Sir Brook Watson: friend of the loyalists, first agent of New Brunswick in London,” Argosy (Sackville, N.B.), 3 (1924–25): 3–25.

Many valuable studies remain in dissertation form, including T. F. Buttimer, “Governor Thomas Carleton: unsung and unpopular” (ba thesis, Mount Allison Univ., Sackville, 1977); Condon, “Envy of American states”; C. L. Duval, “Edward Winslow; portrait of a loyalist” (ma thesis, Univ. of N.B., Fredericton, 1960); D. R. Facey-Crowther, “The New Brunswick militia: 1784–1871” (ma thesis, Univ. of N.B., 1965); J. S. MacKinnon, “The development of local government in the city of Saint John, 1785–1795” (ma thesis, Univ. of N.B., 1968); P. A. Ryder, “Ward Chipman, United Empire Loyalist” (ma thesis, Univ. of N.B., 1958); and J. P. Wise, “British commercial policy, 1783–1794: the aftermath of American independence” (phd thesis, Univ. of London, 1972). The thesis by Twila Buttimer considerably influenced the sympathetic handling of Carleton offered in this biography. w.g.g.]

Cite This Article

W. G. Godfrey, “CARLETON, THOMAS,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 5, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed April 24, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/carleton_thomas_5E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/carleton_thomas_5E.html |

| Author of Article: | W. G. Godfrey |

| Title of Article: | CARLETON, THOMAS |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 5 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1983 |

| Year of revision: | 2021 |

| Access Date: | April 24, 2025 |