Source: Link

FANNING, DAVID, loyalist partisan, politician, and author; b. 25 Oct. 1755 in the settlement of Birch (or Beech) Swamp, Amelia County, Va, son of David Fanning; m. April 1782 Sarah Carr, and they had three children; d. 14 March 1825 in Digby, N.S.

Although born in Virginia, David Fanning spent his early life in North Carolina. An eight-year-old orphan in July 1764, he was bound to Needham Bryan (Bryant), a county justice who provided for his education. In 1773, when Fanning was 18 and of legal age to leave his guardian, he moved to Raeburn’s Creek in the western section of South Carolina, where he farmed and traded with the Indians.

At the time of the outbreak of civil war and rebellion in colonial America, Fanning was a company sergeant in the Upper Saluda militia of South Carolina, which was assembled in July 1775 “to see who was friends to the King and Government, and . . . who would Join the Rebellion.” Because the up-country militia tended to support the royal cause, the Council of Safety in Charleston dispatched a mission to persuade these “loyal Americans” to think in terms of rebellion. Although peace between the factions was maintained for a time, it was shattered in November with the arrest by the rebels of a prominent loyalist and the rumour of a patriot scheme to “Bring the Indians Down into the Settlement where the Friends of Goverment Livd to murder all they Could.” Under Major Joseph Robinson* the loyal militia, including Fanning, besieged the rebels at Ninety-Six, and on 22 November the latter “were forst to Surrender, and give up the Fort and Artillery.” This success prompted a large-scale rebel invasion from both the Carolinas into the South Carolina up-country, which ended with the dispersal of the loyalist faction at Big Cane Brake in December. Having narrowly eluded capture, Fanning fled to the Cherokee Indians.

Fanning was now staunchly committed to the cause of the king. He was motivated, apparently, by the fact that he had been pillaged of his trade goods by a rebel group and because the patriots had broken their word of honour not to molest loyalists. His sympathies well known, he was made a prisoner by the rebels in January 1776 – the first of 14 incarcerations or captures over the next three years. Though on occasion released, he also brought off a number of daring escapes; however, ill treatment in prison and long months in hiding took their toll. By early 1779 his situation was miserable, and he described himself as looking “So much like a Rack of nothing But Skin and bones and my wounds had never been Drest and my Clothes all bloody.” When he encountered a young girl with whom he was acquainted, she ran off in horror, saying that “I was Dead and that I then was a Sperit and Stunk yet.” Tired, discouraged, and becoming desperately ill, Fanning negotiated with the rebels, and received a conditional pardon. He consequently returned home and agreed in principle to remain neutral and to guide rebel units through the woods upon request.

The expedition of the royal forces to South Carolina in 1780, and the capture of Charleston on 12 May, renewed the hopes of the “loyal Americans” in the province, many of whom – Fanning among them – organized themselves into the “bloody scout” and assisted the regular and provincial troops over the next several months. During this campaign colonial Americans fought each other in an increasingly brutal fashion. By the end of October, the loyalists had lost the initiative, however, and Fanning removed to North Carolina. There he occupied himself recruiting followers in anticipation of an advance north by Lord Cornwallis.

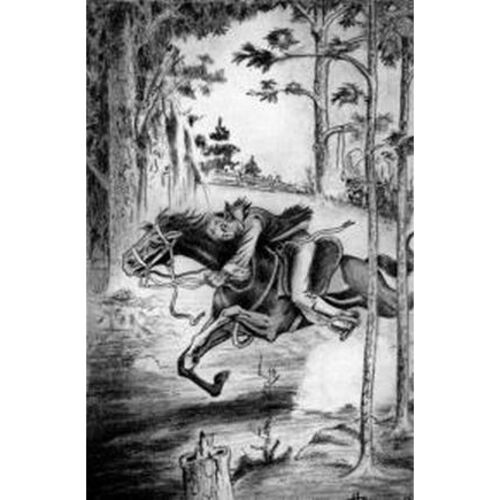

In February 1781 Cornwallis raised the royal standard at Hillsborough, N.C., and called for local support. Although he had informed the now popular and influential Fanning in January that he could not give him a command suitable to his standing, the zealous loyalist partisan continued to raise men for the royal cause. Yet all but about 50 of the 500 he recruited were sent home because of the almost total lack of arms and provisions. On 5 July Fanning was appointed by Major James Henry Craig* colonel of the loyal militia of Chatham and Randolph counties, N.C., and for several months he conducted raids “in the interior parts of N. Carolina,” the civil war having continued unabated after Cornwallis’s departure for Virginia in May. At Hillsborough, for example, Fanning led 1,220 loyal militia in a classic surprise attack early on 12 September, captured the rebel governor of North Carolina, and took more than 200 prisoners.

Fanning continued the struggle long after the surrender of Cornwallis at Yorktown in October 1781. By the spring of 1782, however, he had finally decided to “settle myself being weary of the disagreeable mode of Living I had Bourne with for some Considerable time.” As a first step in attempting to establish a normal life, he married Sarah Carr, a 16-year-old woman from the settlement of Deep River in North Carolina. In June the two arrived at Charleston, which was overflowing with loyalist refugees, and in November, a month before the British evacuation of the city, they went with other loyal refugees to St Augustine, East Florida. Since by the terms of the Treaty of Paris the Floridas were returned to Spain, Fanning sought yet another new home. After a futile attempt to reach the Mississippi, he went to Nassau in the Bahamas and then to New Brunswick, where he arrived on 23 Sept. 1784.

By 1787 Fanning had acquired property in Kings County. He resided there until he moved, some time after 1790, to Kembles Manor in Queens County, where he farmed, operated a grist mill, and built a sawmill. During these years Fanning made diligent efforts to gain compensation for his services during the rebellion. Like those of most loyalists, the claim he presented to the loyalist claims commission, for £1,625 10s. 0d., was probably inflated, yet the commissioners’ award of £60 seems ridiculously low for a man whose exertions in the British cause, they acknowledged, had been “very great and exemplary.” It was in support of his claim for further compensation that Fanning wrote his Narrative (completed in 1790), which details “astonishing events” pertaining to his personal exploits during the civil war and rebellion years. After 1800 he managed to secure an annuity of £91 55s. 0d. for his military service.

From 1791 until January 1801 Fanning served in the House of Assembly for Kings County. His political career was modest and uneventful; among other things he was appointed chairman of the committee of the whole house in 1793, introduced a bill the next year concerning earmarks on animals for identification, and sat on a select committee which studied a bill he himself had put forward in 1798 to register all marriages, births, and deaths in the province. Until 1795 he supported the assembly on many of the issues that set the elected house and the executive at odds, including James Glenie*’s Declaratory Bill, but his political ambitions later led him to support the administration.

Unfortunately, Fanning had the distinction of being the first member of the New Brunswick assembly expelled for a felony conviction. In July 1800 he was accused of attempting to rape Sarah London, “fifteen and stout,” who was described as “a talking bold person, but unimpeachable on the article of chastity.” In a deposition before John Golding, a justice of the peace, Sarah stated that she had visited the Fanning house, found David Fanning alone, and refused his invitation to join him. He then, she reported, “dragged her into his house and . . . used his utmost efforts to have Carnal knowledge of her.” Two days later she changed her story – and the charge – from attempted rape to rape. Tried in October before a court of oyer and terminer, Fanning was pronounced guilty, in spite of inconclusive and contradictory evidence; Chief Justice George Duncan Ludlow* sentenced him to death. Fanning believed that the jury had been prejudiced against him because of his personality, his war record which many felt had been brutal and cruel, and his political ambitions (he was actively attempting to replace Golding as a justice of the peace). With his assessment of the situation his lawyers, Thomas Wetmore and Charles Jeffery Peters*, largely agreed. The causes of the prejudice, in their view, were Fanning’s “foolish Publication of transactions in which he was concerned during the American War . . . his rash conduct in many instances during his residence in the Province – and . . . an unfortunate violence of temper by means of which he has made many enemies who are glad to seize every opportunity of holding him forth in the most unfavorable light.” Protesting his innocence and alleging a biased jury, Fanning appealed to Lieutenant Governor Thomas Carleton* for a pardon. It was granted, but Fanning was exiled from the province forever.

With the exception of a brief interlude at Annapolis Royal, Fanning spent the remainder of his life in the Digby area, where he eventually built a comfortable house and where he engaged in farming, fishing, and shipbuilding. All his petitions and letters to Thomas Carleton, Provincial Secretary Jonathan Odell*, and others requesting permission to return to New Brunswick to settle his business affairs were frustrated. He died in Digby on 14 March 1825. Tough, wiry, plagued for a time by scald-head or tetterworm, Fanning was a stubbornly determined man who was a zealous and often brilliantly effective loyalist military leader. He was not a gentle man nor was he that type of philosophical loyalist, exuding refinement and contentment, who sat out the war in relative comfort in New York, Charleston, or England. Fanning fought tenaciously, fiercely, and sometimes cruelly against his ex-friends and neighbours, and his successes made him unpopular with the privileged loyalist “nabobs” of New Brunswick. His inflexible, even brutal, resolution notwithstanding, his epitaph in the Trinity churchyard at Digby reads in part: “Humane, affable, gentle, and kind – A plain honest open moral mind.”

The original manuscript of David Fanning’s narrative has been lost. An incomplete but apparently faithful transcription prepared around 1890 is preserved among the Fanning papers at the N.B. Museum and forms the basis of a modern edition entitled The narrative of Col. David Fanning, ed. L. S. Butler (Davidson, N.C., and Charleston, S.C., [1981]). The introduction of this work includes a detailed discussion of the journal’s publication history, but mention should be made here of the first edition, a heavily edited version of the original manuscript entitled The narrative of Colonel David Fanning, (a tory in the revolutionary war with Great Britain;) giving an account of his adventures in North Carolina, from 1775 to 1783 . . . , intro. J. H. Wheeler, ed. T. H. Wynne (Richmond, Va., 1861), and of a subsequent Canadian edition, Col. David Fanning’s narrative . . . , ed. A. W. Savary (Toronto, 1908), which is also heavily edited but valuable because it contains the only surviving version of the final portion of Fanning’s account.

PANB, RG 2, RS8, crime, 3/l, David Fanning case, 1800–2. Private arch., Harold Denton (Digby, N.S.), Family Bible. PRO, AO 13, bundles 137–38; PRO 30/ 11/84: 31–32. Trinity Church Cemetery (Digby), Tombstone inscription. Loyalists in East Florida, 1774 to 1775; the most important documents pertaining thereto, ed. W. H. Siebert (2v., De Land, Fla., 1929; repr., intro. G. A. Billias, Boston, 1972). N.B., House of Assembly, Journal, 1791–1801. “United Empire Loyalists: enquiry into losses and services,” AO Report, 1904. R. C. DeMond, The loyalists in North Carolina during the American revolution (Durham, N.C., 1940). [G.] C. Watterson Troxler, “The migration of Carolina and Georgia loyalists to Nova Scotia and New Brunswick” (phd thesis, Univ. of N.C., Chapel Hill, 1974). J. L. Wright, British St. Augustine (St Augustine, Fla., 1975). G. D. Olson, “Loyalists and the American revolution: Thomas Brown and the South Carolina backcountry, 1775–1776,” S.C. Hist. Magazine (Charleston), 68 (1967): 201–19; 69 (1968): 44–56. [G.] C. Watterson Troxler, “‘To git out of a troublesome neighborhood’: David Fanning in New Brunswick,” N.C. Hist. Rev. (Raleigh), 56 (1979): 343–65.

Cite This Article

Robert S. Allen, “FANNING, DAVID,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 6, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed December 27, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/fanning_david_6E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/fanning_david_6E.html |

| Author of Article: | Robert S. Allen |

| Title of Article: | FANNING, DAVID |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 6 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1987 |

| Year of revision: | 1987 |

| Access Date: | December 27, 2025 |