Source: Link

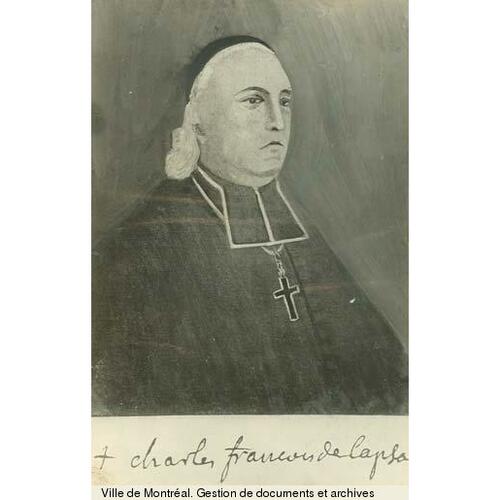

BAILLY DE MESSEIN, CHARLES-FRANÇOIS, coadjutor bishop of Quebec; b. 4 Nov. 1740 at Varennes, near Montreal (Que.), eldest son of François-Augustin Bailly de Messein and Marie-Anne de Goutin; d. 20 May 1794 at Quebec.

The Bailly de Messein family is believed to have been ennobled in the 16th century, and the first of the family to leave France and settle in Canada was Nicolas, son of Michel and Anne Marsain, who came as an ensign in the colonial regular troops around 1700. In 1706 he was married in Quebec to Anne Bonhomme; in 1732 he was promoted lieutenant, and on 27 Sept. 1744 he died in Quebec at the age of 80. One of their two surviving children was François-Augustin, who had been born on 20 Aug. 1709. Like most French and Canadian noblemen, he chose a wife from the upper class, marrying Marie-Anne, the daughter of François-Marie de Goutin* and Marie-Angélique Aubert de La Chesnaye, of Île Royale (Cape Breton Island). The marriage contract was signed by such prominent men as Intendant Michel Bégon* de La Picardière, Charles Le Moyne* de Longueuil, Baron de Longueuil, and Louis-Joseph Rocbert de La Morandière, the king’s storekeeper. François-Augustin went into business, first in Montreal and then at Varennes. He died in 1771; his widow lived until 1804.

Of François-Augustin’s 16 children the best known was unquestionably his eldest son, Charles-François, whose godparents were Josué Dubois* Berthelot de Beaucours, governor of Montreal, and Marie-Charlotte Denys de La Ronde, widow of former governor Claude de Ramezay*. François-Augustin had prospered sufficiently to send his two oldest sons to do their classical studies at the Collège Louis-le-Grand in Paris around 1755. It is certain, however, that Charles-François did his year of rhetoric, the senior class, after he returned to Quebec in 1762. He is said to have come back from France with rather haughty manners and with needs that even his father’s means could not support. The young man is supposed to have made approaches at this time to one of the daughters of Luc de La Corne, but when she responded with no more than friendship Charles-François decided to enter the Grand Séminaire de Québec.

On 10 March 1767 he was ordained priest and he left immediately for Nova Scotia to replace Pierre Maillard*, who had been missionary to the Micmacs and Acadians there until his death in 1762. Lieutenant-Governor Guy Carleton*, who had already noticed young Bailly, is supposed to have asked Bishop Briand to appoint him to this sensitive mission. The governor of Nova Scotia, Lord William Campbell, was well pleased with the missionary, since he succeeded in pacifying the Indians and reassuring the Acadians who had just taken the oath of loyalty to George III. The young priest, however, felt isolated from Quebec and asked the bishop to recall him. He was back in 1772 and was appointed to teach the rhetoric and belles-lettres classes at the Petit Séminaire; in 1774 he was also elected one of its directors for two years.

In 1776, probably because of his peacemaking mission in Nova Scotia, Bailly became chaplain to Louis Liénard* de Beaujeu de Villemomble’s volunteers, with the purpose of preaching loyalty to England and thwarting the intrigues of the American invaders, who were causing havoc in the parishes on the south shore of the St Lawrence from Saint-Thomas-de-Montmagny (Montmagny) to Notre-Dame-de-Liesse-de-la-Rivière-Ouelle (Rivière-Ouelle). That spring Bailly was shot in the abdomen and taken prisoner by the Americans [see Michel Blais]. Soon released, he returned to convalesce at the seminary and teach theology in 1777, before being named parish priest for Saint-François-de-Sales at Pointe-aux-Trembles (Neuville) in September.

In the ten years since his ordination Charles-François Bailly had progressed through the phases of an ecclesiastical career similar to that of many Canadian priests in the second half of the 18th century. Tall and handsome, he had acquired polish and ease in his manners and speech at the Collège Louis-le-Grand, where there were many sons of noblemen. It was this refinement that had doubtless brought him to Carleton’s attention. The success of his mission in Acadia and the praise it had won him from the governor of Nova Scotia promised Bailly a brilliant future, if he were ambitious.

In 1774 Carleton had returned to Quebec with a young wife who had grown up at Versailles, and three children to provide with an education worthy of their parents. The governor therefore had sent for Bailly de Messein, whose loyalty was unquestioned and who had experience in teaching. Tradition has it that the tutor, wearing a silk cassock, used to travel to and fro between the seminary and the Château Saint-Louis in the governor’s coach. When Carleton had to leave for England in July 1778, he was understandably anxious to take his children’s tutor with him. Thus Bailly went to England and there was introduced to London society. Probably in order to maintain a tangible link with his parishioners at Pointe-aux-Trembles, he had one of them, young François-Xavier Larue, later a notary in the village, accompany him.

In 1782 Bailly returned to Canada and to his parish, which he had entrusted to Joseph-Étienne Demeule during his absence in England – an absence Bishop Briand had disapproved of but was unable to prevent. Bailly attended to his parish until 1786; he directed it according to the rules of ecclesiastical discipline, was always obliging to neighbouring parish priests, and was exemplary in conduct and character. When Carleton, now Lord Dorchester, returned to Quebec as governor in 1786, the parish priest of Pointe-aux-Trembles came back to the Château Saint-Louis, where his conversation and society were much sought after; but this association in turn brought him the label, in certain circles, of “the parish priest of the English.”

As it happened, Louis-Philippe Mariauchau d’Esgly, bishop of Quebec for the previous two years, had had to wait until the governor’s arrival to consecrate his coadjutor, Bishop Hubert, for whom bulls had reached Quebec early in June 1786. On 29 November Bishop Hubert received episcopal unction at the hands of retired Bishop Briand, who was attended by Henri-François Gravé* de La Rive, a priest from the seminary, and Bailly de Messein. When Bishop Mariauchau d’Esgly died in June 1788, Bishop Hubert had to choose a coadjutor. Dorchester designated his friend Bailly de Messein. Even though the candidate was not to the bishop’s liking, it was necessary to avoid offending the governor, who had given many generous privileges to the Catholic Church and to the Canadians, especially since Bailly was in fact an educated and zealous priest. In September 1788 Bailly was named bishop in partibus infidelium of Capsa and on 12 July 1789 he was consecrated by Hubert, who was attended by Gravé and Pierre-Laurent Bédard. For the ceremony the priests and pupils of the seminary provided music that was beautiful and very moving. There were few priests present; “Monseigneur l’Ancien,” as Bishop Briand was called, seemed inconsolable, and Bishop Hubert overwhelmed. Afterwards, at a meeting in Bishop Briand’s residence with Joseph-Octave Plessis* and Gravé present in addition to Hubert and Bailly, Hubert is supposed to have notified his coadjutor that he was to return to Pointe-aux-Trembles, since he had made him bishop only to retain the bishopric for the province. In August Bailly asked Bishop Hubert to advise him, in writing, of his powers and whether Quebec or Montreal was to be his place of residence. Hubert replied that his grant to him of letters as vicar general on 20 June 1788 had been to honour Bailly’s dignity as coadjutor and not to relieve himself of his episcopal duties, that the coadjutor was free to live wherever he pleased, but that the bishop could not give him two parish charges to provide for his newly added expenses. Hubert did however grant him half the income from the tithe of the parish of Saint-Ours in addition to his parish at Pointe-aux-Trembles. “The Château’s bishop” had a way of life to keep up, and he aspired to high office, knowing perhaps that Hubert had received permission from Rome to install a bishop in Montreal.

Hubert thought of sending his coadjutor to visit the Acadian missions in the summer of 1790. But relations between them were soon to deteriorate over a plan for a university and the abolition of certain public holidays. On 13 Aug. 1789 Chief Justice William Smith, who had been charged with inquiring into education in the province of Quebec, had written the two bishops to ask their opinion on the founding of a non-sectarian university. Bishop Hubert acknowledged the letter the day he received it but did not reply until 18 November, after reflecting, consulting people, and sending his report to his coadjutor. On 26 November Smith, as chairman of what was the first fact-finding commission on education in the province of Quebec, submitted his report to Dorchester, who published it in February 1790. On 5 April Bishop Bailly sent Smith a letter in favour of the mixed-university plan; presenting arguments opposite to those of Bishop Hubert, he called him a rhapsodist, even held out against him the threat of the revolution, and made a show of believing that the bishop of Quebec’s reply had been dictated to him by someone else. The coadjutor sent a copy of his letter to Bishop Hubert. Embittered at having no role in the administration of the diocese, Bishop Bailly later took advantage of circumstances to attack his bishop again, this time publicly, in the Quebec Gazette. On 29 April he published a letter he had sent to the bishop about Hubert’s slowness in abolishing certain public holidays. That was going too far. Some of the clergy and lay people in Quebec, Montreal, and rural areas publicly expressed disapproval of the bishop of Capsa; the Montreal Gazette commented ironically on the situation [see Fleury Mesplet]. In October, after a few months’ lull, Bishop Bailly’s statement on the project for a university was published. It is now known, through Samuel Neilson’s records, that Charles-Louis Tarieu* de Lanaudière paid for the printing. A month later the Quebec Gazette carried a petition addressed to the governor requesting the creation in the province of Quebec of a university to be endowed with a royal charter and to be open to all religious denominations. The petition was signed by 175 persons, of whom 56 were French speaking. Bishop Bailly, Father Félix Berey Des Essarts, the Recollet superior, and Edmund Burke*, who had just left the Séminaire de Québec, were among those signing. The Montreal Gazette published articles denouncing the bishop of Quebec as ignorant and requesting at the same time the creation of the university.

Bishop Hubert, who made no comment in the newspapers, was so affected by these public debates that he felt obliged to write about them to Lieutenant Governor Alured Clarke* and to Cardinal Leonardo Antonèlli in Rome. The cardinal sided entirely with Bishop Hubert, sending him a letter for the coadjutor in which he threatened to remove Bailly from office if he did not mend his ways. Bishop Bailly seems to have adopted a more reasonable attitude even before the letter arrived from Rome, since the bishop of Quebec did not deliver it to him. After April 1790 all relations between the two bishops were broken off, and Bailly no longer went to the seminary. Priests no longer came to see him. Even the Château Saint-Louis seemed to treat him coldly. He attended to the affairs of his parish and often visited the sisters of the Congregation of Notre-Dame, who had a convent at Neuville and whom he personally aided by paying for the education of several young girls. His friend, Father Berey, would come to see him and entertain him. The presence of Bishop Bailly was noted at least once in Quebec society when he baptized Édouard-Alphonse*, son of Ignace-Michel-Louis-Antoine d’Irumberry* de Salaberry, and godson of Prince Edward Augustus*. In 1793 his health began to fail, and Father Berey came to live with him.

In April 1794, Bailly, much feebler, put his affairs in order and made his will in the presence of notary François-Xavier Larue. He gave £1,000 to his former mission in Acadia, £500 to his sister Félicité-Élisabeth, the wife of Jacques Le Moyne de Martigny, £700 to his “butler,” Donald Mac-Donald, and the rest of his personal and real estate to the poor of Neuville and of Saint-Jean-Baptiste-des-Écureuils, a neighbouring parish. He was then taken by rowboat, via the St Lawrence and the Saint-Charles, to the Hôpital Général in Quebec. He made his peace with Bishop Briand and Bishop Hubert before breathing his last on 20 May. His body was on public view at the Hôpital Général for two days, and then was taken to Neuville, where he had wanted to be buried. The funeral service, held on 22 May, was attended by a large gathering of fellow priests and friends, and the vicar general, Gravé de La Rive, gave the absolution. The coffin was placed under the high altar on the north side. On 5 June the parish priest of Saint-Joseph-de-la-Pointe-Lévy, Jean-Jacques Berthiaume, published a short notice of the bishop of Capsa’s death in the Quebec Gazette, mentioning that before he died Bishop Bailly had asked his bishop’s pardon in the presence of witnesses. John Neilson* was obliged to apologize to Bishop Bailly’s family and friends in the next issue of the Gazette, saying that the announcement had appeared without his authorization and that he had not wanted to tarnish the reputation of the deceased.

In French Canadian historiography Bailly de Messein has been judged harshly, and only in the writings of the sisters of the Congregation of Notre-Dame and of the Hôpital Général in Quebec is there any praise. In 1954 Émile Castonguay made a timid attempt to do him justice, but he continues to be ignored in textbooks. He could not even serve as a foil in French Canada’s ecclesiastical golden legend, as did the renegade Charles Chiniquy*. He was not a bad priest – quite the contrary. He carried out with zeal all the missions and duties his bishop assigned him, and he administered his parish in an exemplary manner before and after his voyage to England. His noble rank, imposing appearance, talents as orator and conversationalist, and classical studies at the most distinguished college in France, had all brought him to the attention of the civil authorities. His loyalty to the crown had been the final factor in making him feel destined for the highest ecclesiastical offices, which he thought he had attained as coadjutor. Then he made the error of contradicting his bishop in public, thus humiliating him in front of the Catholics and, above all, in front of the English Protestants. The tone of some of his remarks was that of the enlightened man denouncing his bishop’s despotism and obscurantism.

The catalogue of books in his library might have confirmed that he had an affinity for the philosophes. But in fact it does not. First and foremost it contains books on theology and religion, then literary works and books on history, geography, the arts, and science. There are only two works by Voltaire, Jean-Jacques Rousseau’s Lettres écrites de la montagne and his Œuvres, and three books about Rousseau, one on the Contrat social. In short, this was the library of a good priest; the dozen books of Latin poets are witness to his classical studies under the Jesuits.

A collection of more than 1,200 volumes was certainly rare for a Canadian priest before 1800. It indicates that the owner, if not wealthy, at least was reasonably well off. The inventory after death reveals that Bailly had as much personal property as parish priests of that period were allowed, a well-filled stable and barn, a loft filled with wheat and oats, and a fully furnished presbytery. Table silver and flat candlesticks and candelabras stamped with his monogram attest to his rank as nobleman and bishop, as does the fact that he had a butler and two maids. Although some money was owing him, he apparently owed more to his creditors, the largest sum to his friend Louis Langlois, dit Germain, a merchant and bookseller.

Perhaps sensing that after his death he would be forgotten, during his lifetime he had given the name of his episcopal title, Capsa, to a back concession at Neuville. In June 1969 the archbishop of Quebec had Bishop Bailly’s remains transferred to the crypt of the basilica of Notre-Dame in Quebec.

[C.-F. Bailly de Messein], Copie de la lettre de l’évêque de Capsa, coadjuteur de Québec, &c, au président du comité sur l’éducation . . . ([Québec, 1790]).

AAQ, 12 A, D, 109; 20 A, II, 49, 51; 22 A, V, 275. ACND, 312.640/1–2. AHGQ, Communauté, Journal, II, 239. ANQ-Q, AP-P-84; AP-P-86; Greffe de F.-X. Larue, 11 avril 1794. ASN, AP-G, L-É. Bois, Succession, XVII, 1, 3. ASQ, C 35, pp.268–69, 311; Lettres, M, 136, 138; P, 145; S, 6bis, C, I; mss, 12, ff.41, 43, 45; 13, 12 août 1774, 10 août 1800; 433; mss-m, 228; Polygraphie, VII, 134; XVIII, 65; XIX, 64b; Séminaire, 16, no.23. AUM, P 58, Corr. générale, C.-F. Bailly à Panet, 14 sept. 1782, 27 mars 1786. Bibliothèque du séminaire de Québec, A.-G. Dudevant, “Catalogue des livres de la bibliothèque du séminaire des Missions étrangères de Québec fait dans le mois de may 1782” (copy at ASQ). Mandements des évêques de Québec (Têtu et Gagnon), II, 385–426. PAC Rapport, 1890, 219, 261, 287. Montreal Gazette, 6, 13, 27 May, 3, 10 June, 4, 18, 25 Nov. 1790. Quebec Gazette, 6 July 1789; 29 April, 13, 27 May, 4 Nov. 1790; 2, 12 June 1794. [F.-]M. Bibaud, Le panthéon canadien; choix de biographies, Adèle et Victoria Bibaud, édit. (2e éd., Montréal, 1891), 193–94. Caron “Inv. de la corr. de Mgr Hubert et de Mgr Bailly de Messein,” ANQ Rapport, 1930–31, 199–299. Henri Têtu, Notices biographiques: les évêques de Québec (Québec, 1889), 392–429. Tremaine, Bibliography of Canadian imprints. Audet, Le système scolaire, II, 191–208. Ghislain Bouchard, “Les fêtes d’obligation en Nouvelle-France, du début de la colonie à 1791” (mémoire de licence, université Laval, Québec, 1955). O’Reilly, Mgr de Saint-Vallier et l’Hôpital Général, 466–67. P.-G. Roy, La famille Bailly de Messein (Lévis, Qué., 1917). E. C. Bailly, “The French-Canadian background of a Minnesota pioneer: Alexis Badly,” BRH, LV (1949), 137–75. M.-A. Bernard, “Mgr Charles-François Bailly de Messein,” BRH, IV (1898), 348–50. Bernard Dufebvre [Émile Castonguay], “Mgr Bailly de Messein et un projet d’université en 1790,” L’Action catholique; supplément (Québec), XVIII (1954), nos. 10, 11. Placide Gaudet, “Un ancien missionnaire de l’Acadie,” BRH, XIII (1907), 244–49. Ignotus [Thomas Chapais], “Notes et souvenirs,” La Presse (Montréal), 6 avril 1901, 8; 20 avril 1901, 9; 4 mai 1901, 8.

Cite This Article

Claude Galarneau, “BAILLY DE MESSEIN, CHARLES-FRANÇOIS,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 4, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed December 31, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/bailly_de_messein_charles_francois_4E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/bailly_de_messein_charles_francois_4E.html |

| Author of Article: | Claude Galarneau |

| Title of Article: | BAILLY DE MESSEIN, CHARLES-FRANÇOIS |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 4 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1979 |

| Year of revision: | 1979 |

| Access Date: | December 31, 2025 |