Source: Link

RAMEZAY, CLAUDE DE, esquire, lieutenant and captain in the colonial regular troops, commander of the troops, seigneur, knight of the order of Saint-Louis, governor of Trois-Rivières and governor of Montreal, acting governor of New France from 1714 to 1716, builder of the Château de Ramezay, famous Montreal landmark; b. at La Gesse, in the province of Burgundy, 15 June 1659; d. in Quebec, 31 July 1724.

Ramezay appears to be derived from the Scottish name Ramsay. The family probably emigrated from Scotland to France in the late 15th or early 16th century and settled in Burgundy. There they acquired the fiefs of La Gesse, Montigny, and Boisfleurant and entered the nobility.

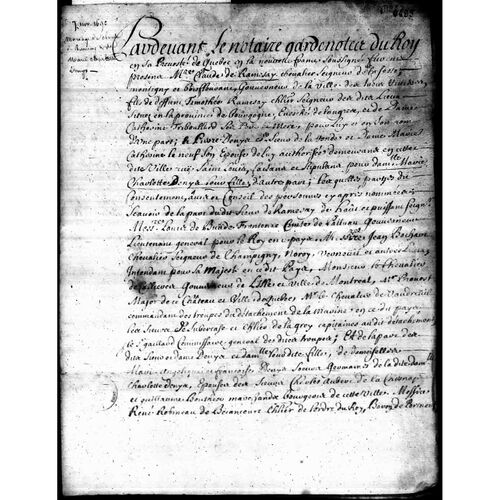

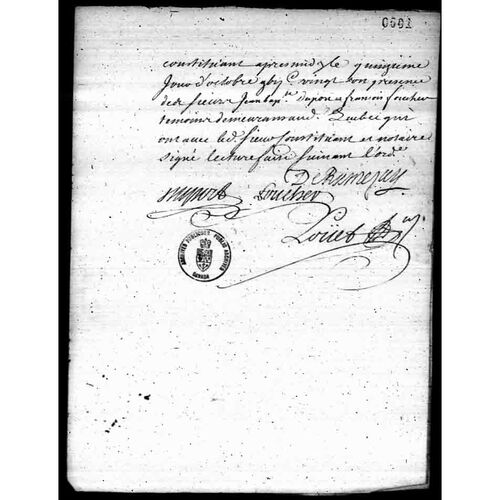

Claude de Ramezay was a son of Timothé de Ramezay and Catherine Tribouillard, daughter of Hilaire Tribouillard, intendant in charge of the extensive stables of the Prince de Condé. He came to Canada in 1685 as a lieutenant in the colonial regular troops and was promoted to the rank of captain two years later. On 8 Nov. 1690, in Quebec, he married Marie-Charlotte Denys, a daughter of Pierre Denys de La Ronde and Catherine Leneuf and thus became linked to one of New France’s leading families. A few months earlier he had obtained the post of governor of Trois-Rivières by paying a sum of 3,000 livres to the destitute widow of the late incumbent, René Gaultier* de Varennes. Only five years after his arrival in the colony, Ramezay had become a member of its social and political elite.

With a population of only 358 in 1698, Trois-Rivières was nothing more than a large village; but being located halfway between Montreal and Quebec it was a convenient resting place for persons travelling between the two towns. This placed a heavy burden on the finances of the local governor, who was expected to entertain the notables passing through his district. Ramezay, however, was somewhat vain and like most members of his class regarded money chiefly as a means of achieving social status. Hosting the colony’s dignitaries and being referred to as a “real gentleman” by Governor Frontenac [Buade*] himself must have greatly flattered his ego. Indeed, it may have been to impress his many guests that he embarked upon an ambitious building programme. He built a large two-storey house and a number of outbuildings on land he had purchased on the seigneury of Platon Sainte-Croix and another still larger house on the other side of town. In 1699, Bishop Saint-Vallier [La Croix] purchased these properties for 21,000 livres and transferred them to the Ursuline nuns.

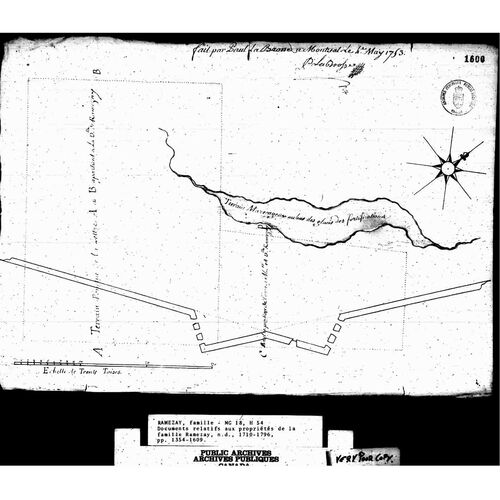

Ramezay did some useful work in his official capacity. Soon after taking office he ordered the town to be fortified and this was promptly done under the supervision of the engineer, Dubois* Berthelot de Beaucours. The new governor, however, does not appear to have been popular with the townspeople. He was brusque and ill-tempered. Moreover, since neither his salary nor a series of gratuities ranging in amount from 300 to 2,000 livres sufficed to maintain his station in Canadian society and to support his large family, he turned to the fur trade. According to Le Roy de La Potherie, the governor angered the local merchants by depriving them of high quality pelts and annoyed the Indians by interfering with their freedom of trade. La Potherie reports that there was rejoicing in Trois-Rivières in 1699 when Ramezay left to become commander of the Canadian troops.

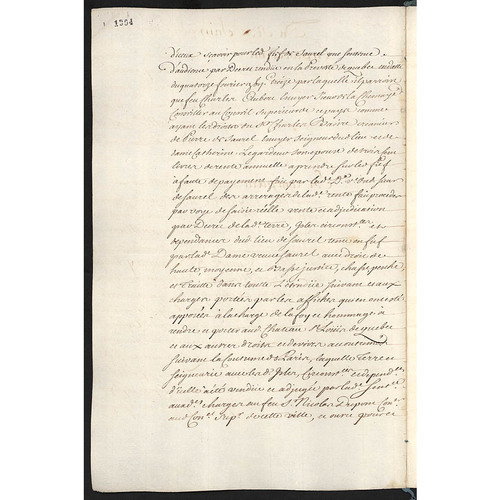

Ramezay held this new position for five years and served satisfactorily. He returned from a voyage to France with 300 recruits in 1702 and received the cross of Saint-Louis the following year. In 1704 he succeeded Philippe de Rigaud de Vaudreuil as governor of Montreal. His reputation as a builder had preceded him to that city, and predictably enough one of his first concerns was to provide himself with a residence worthy of his new position. He purchased a lot on Rue Notre-Dame from his relative, Nicolas d’Ailleboust de Manthet, and in April 1705 retained the services of the master mason and architect, Pierre Couturier. The latter undertook to build a house 66 feet long, three storeys high (including the attic), and with four chimney-stacks. The walls were to be three and one half feet thick below ground level and two and one half feet thick above. The building was completed the following year and the proud owner described it as “unquestionably the most beautiful in Canada.”

Ramezay’s extravagance coupled with the losses he suffered in 1704 when the flute Seine was captured by the English soon landed him in severe financial difficulties. To make ends meet he harassed the minister with requests for gratuities, tried without success to sell his house to the crown for 18,000 livres, borrowed large sums of money from a number of persons, including 3,000 livres from Samuel Vetch, and failed to repay his debts until compelled to do so by the minister of Marine or the colonial authorities. Naturally, he also engaged in the fur trade. “The Sieur de Ramezay,” reads a complaint from Montreal, “is completely involved in trade and . . . he gives all the members of his numerous family the means of pursuing it in preference to all other habitants.” His most interesting initiative, however, was his venture into lumbering. He had a sawmill operating at Baie Saint-Paul as early as 1702 and he built another in the Montreal area in 1706. The following year he advised Pontchartrain that over 20,000 feet of boards and sheathing could be produced in the district of Montreal every year and he suggested that this wood be used to launch the shipbuilding industry in Canada.

By 1704 Ramezay had become one of Canada’s leading personalities but the position he occupied did not fully satisfy him. He was ambitious, had a factious disposition, and by his marriage had become enmeshed in the intricate web of New France’s family rivalries. Soon he was filling his dispatches with virulent attacks against another Canadianized Frenchman, Philippe de Rigaud de Vaudreuil. He accused the governor of sending agents into the west to engage in the fur trade, of being a pawn of the Jesuits, of having failed to adopt adequate security measures when a New England delegation visited the colony in 1705, and of having faltered when a riot broke out in Montreal over the high price of salt. Lamothe Cadillac [Laumet] and Ruette d’Auteuil joined in this campaign, and for a time they succeeded in seriously undermining Vaudreuil’s position at Versailles. The governor, however, counterattacked vigorously. Ramezay, he charged, had formed a cabal with the other two in order to profit from the Detroit trade; his violent temper made him unfit to govern. Ramezay heatedly denied these charges. He had once held a sixth interest in Detroit, he admitted, but had given it up in order to avoid even the suspicion of placing his private fortune before the public good. He conceded that he had “a quick temper” but maintained that he had never mistreated anyone in 15 years, unlike Vaudreuil who in a moment of anger had been known to slap a man in the face and kick him in the stomach.

Meantime, as a result of the outbreak of the War of the Spanish Succession in Europe, a state of war existed between New France and the English colonies to the south. This exposed Quebec to naval attack, but Montreal was in a relatively secure position because of the treaty of 1701 with the Iroquois and the non-belligerent policy New York was satisfied to follow during the governorship of Lord Cornbury. But there were other problems to occupy Ramezay’s attention during the early years of the conflict. Frenchmen were still deserting the colony for the west in spite of the edict of 1696, and the contraband trade between Montreal and Albany was reaching frightening proportions because of the saturated condition of the French market. Ramezay assured the minister that he was doing his best to check these practices but he met with no success. Indeed, it is difficult to see what measures he could have adopted since many of the merchants who were heavily involved in this trade were also his creditors for large amounts of money. In 1707, Ramezay did make a valuable suggestion. He urged the crown to send 40,000 livres of merchandise to Canada annually and to make it available to the Indians at cheap rates in order to offset the fall in beaver prices that was driving them to Albany. The French government, whose resources were entirely committed to the European war, was unfortunately unable to act on this suggestion and the contraband trade continued unabated.

In 1709 Ramezay was suddenly called upon to prove himself as a military leader. In the summer of that year New York broke the truce with New France and massed militiamen and Indian auxiliaries, under the command of Francis Nicholson, at the Wood Creek portage near Albany in preparation for an attack on Montreal. Ramezay, at the head of an army of 1,500 men, advanced along the Richelieu against this force. He had been instructed by Vaudreuil to avoid an engagement and to limit himself to wrecking the boats and canoes and to dumping the ammunition into the river. Surprise was of the essence for the success of the operation, but the carelessness of Ramezay’s nephew, the scatter-brained Pierre-Thomas Tarieu de La Pérade, who had been placed in charge of a scouting party, betrayed the presence of the expedition. Shortly after this mishap, Ramezay learned from a prisoner that the English army at Wood Creek numbered 3,000 men. A council of war was held to consider the situation, and the infuriated governor decided that there was nothing to do but retreat.

Fortunately for New France this uninspired performance had no harmful consequences. New York called off the expedition against Montreal after learning that the English naval squadron that was supposed to attack Quebec had been sent to another destination. However, the episode may have struck yet another blow at Ramezay’s sinking political fortunes. By 1709, the governor of Montreal had lost the support of his two old allies, Auteuil and Cadillac. The former had been recalled as attorney general of the Conseil Supérieur and the latter was about to be transferred to Louisiana as a result of Clairambault d’Aigremont’s devastating report. In 1709 also, Madame de Vaudreuil [Joybert] took up residence at the French court and no doubt did what she could to discredit her husband’s most outspoken critic. The blow fell in 1711. In a scathing dispatch, Pontchartrain accused Ramezay of being the chief fomenter of discord in the colony and warned him that Louis XIV would already have made some “unpleasant decisions” had not the minister assured him that the governor of Montreal would mend his ways in the future. Now that his foe was crushed, Vaudreuil sportingly extended the olive branch to him. In 1712 Ramezay’s third son, Charles-Hector, Sieur de La Gesse, was presented to the French court by Madame de Vaudreuil.

In September 1714 Vaudreuil went to France on leave of absence and Ramezay served as acting governor until his return to Canada in the summer of 1716. It was during this period that the British colonies, capitalizing on the recently concluded treaty of Utrecht, made their first attempt to infiltrate the Mississippi Valley and Great Lakes region and to overrun the eastern frontier of New France. Ramezay had to find ways of containing this expansion, a task made all the more difficult by a lack of precedents to indicate a solution and by the return of peace between France and England, which ruled out a military policy. Ramezay forwarded notes to Robert Hunter, the governor of New York, asking him to forbid the merchants of his provinces from sending trading expeditions to the Great Lakes, traditionally a French region, until the boundary was settled. He also sought permission from the Indians of the Mississippi to plunder English supply convoys venturing into the interior. These measures, however, were, at best, expedients. The security of New France, Ramezay informed the court, could only be assured by a favourable settlement of the intercolonial boundary, a question left open by the treaty of Utrecht. If this were not done he warned, “the English will make greater inroads into this colony by way of Acadia, Boston, Manhattan, and the Carolinas in time of peace than when we were at war with them.”

While Ramezay’s analysis of the English threat was remarkably clear-sighted, his organization of the abortive campaign of 1715 against the Fox Indians showed once more that he had a mediocre military mind. Nevertheless, the acting governor cannot be held responsible for all the mishaps that befell the expedition and disrupted it before it was even properly underway. Louis de La Porte de Louvigny, who was supposed to serve as commanding officer, became ill and had to be replaced by the less qualified Constant Le Marchand de Lignery. Because of the court’s refusal to finance the campaign, the army had to be made up entirely of unruly Indians and coureurs de bois. Ramezay, however, was responsible for the strategy which called for the army to advance in separate groups and meet at a point near the Fox stronghold. So complex were these preliminary manoeuvres that they had almost no chance of success. Fortunately, Ramezay learned from these mistakes. In 1716 Louvigny was sufficiently recovered to lead a second expedition against the Foxes. This time the strategy was greatly simplified and the operation was a complete success.

Following Vaudreuil’s return to the colony, Ramezay went back to being governor of Montreal. The sawmill he had built several years before now began to yield attractive dividends. In 1719 he was awarded by the French government a contract to supply 2,000 cubic feet of pine sheathing, 8,000 cubic feet of oak sheathing, and 4,000 feet of board annually for six years. This success appears to have whetted Ramezay’s commercial appetite. In 1723 he asked for fur-trading rights at the post of Kaministiquia but his request was turned down by the minister of Marine.

In spite of the success of his lumber operation and of the praise he won for his conduct of the colony’s affairs in Vaudreuil’s absence, this final period of Ramezay’s life does not appear to have been a happy one. Twice in five years tragedy had struck his family. In 1711 his eldest son, 19-year-old Claude junior, an ensign in the French navy, lost his life in an attack on Rio de Janeiro. His second son, Louis, Sieur de Monnoir, was killed by the Cherokees during the campaign of 1715 against the Fox Indians. It is therefore not surprising that Ramezay’s character should not have mellowed with the passage of years. He quarrelled with the Jesuits when he tried to place a garrison on their mission at Sault-Saint-Louis (Caughnawaga). He charged the Brothers Hospitallers of Montreal with not doing their duty. Finally, he clashed once more with Vaudreuil. How the quarrel began is not clear but it burst into the open in 1723 when the two men publicly disagreed on a point of Iroquois policy. Angered by the manner in which Vaudreuil had spoken to him in the presence of a number of people, Ramezay was soon attacking him in old-time style. A sensational quarrel between these two leading colonial figures appeared in the making, but the governor of Montreal died before it could materialize. Vaudreuil immediately laid past differences aside and spoke warmly of the man who had been both a colleague and a rival for so many years: “He served . . . with honour and distinction” he informed the minister, “and . . . lived very comfortably, having always spent more than his salary, which is the reason he has left only a very small estate to his widow and children.”

Madame de Ramezay had indeed been left in a precarious financial condition which the grant of an annual pension of 1,000 livres did little to improve. To raise the capital she required she tried without success to sell her house, which the intendant, Claude-Thomas Dupuy, had evaluated at 28,245 livres, to the government. With the assistance of a partner, Clément de Sabrevois* de Bleury, she continued to operate her husband’s sawmill, but floodings and the wreck of the Chameau, the vessel which was supposed to carry her lumber to France in 1725, resulted in losses of 10,000 livres. In spite of these setbacks, the Ramezays did not lose their interest in the lumber industry. When the mother died in 1742, her unmarried daughter, Louise*, carried on and expanded the family business. By the mid 1750s she had several sawmills in operation on the seigneuries her father had acquired in the Richelieu region, and one merchant alone owed her 60,000 livres.

Besides Louise, Ramezay was survived by two sons and at least five daughters. La Gesse, the elder of the sons, died on 27 Aug. 1725 in the wreck of the Chameau off Île Royale (Cape Breton Island). The younger, Jean-Baptiste-Nicolas-Roch*, entered the military and is perhaps best remembered as the man who surrendered Quebec to the British in September 1759. Of the five daughters, two became nuns and two others married officers of the colonial regular troops.

Claude de Ramezay did not leave a deep imprint on the history of New France but his career is nonetheless very significant. His marriage into a prominent Canadian family, his clashes with Vaudreuil, the role of grand seigneur, which he played with considerable success in Trois-Rivières and Montreal, provide valuable information on how Canadian society was formed at that time, on the nature of colonial government and politics, and on the mentality and way of life of a representative member of the Canadian upper class.

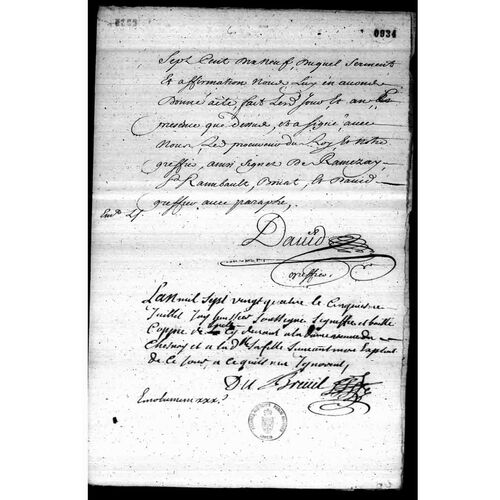

AJM, Greffe d’Antoine Adhémar, 27 avril 1705 (contract between Claude de Ramezay and Pierre Couturier for the construction of the Château de Ramezay). AJQ, Greffe de François Genaple, 7 nov. 1690 (Claude de Ramezay and Marie-Charlotte Denys’ marriage contract). AN, Col., B, 13, 15, 16, 19–20, 22–23, 25, 27, 29, 33–36, 39–45, 47; C11A, 9–48; C11G, 1–3, 5; E, 344 (dossier de Ramezay); F5A, 2; Marine, B1, 8. “Correspondance de Frontenac (1689–99),” APQ Rapport, 1927–28, 1–211; 1928–29, 247–384. “Correspondance de Vaudreuil,” APQ Rapport, 1938–39, 12–179; 1939–40, 355–463; 1942–43, 399–443; 1946–47, 371–460; 1947–48, 137–39. “Un mémoire de Le Roy de La Potherie sur la Nouvelle-France adressé à M. de Pontchartrain, 1701–1702,” BRH, XXII (1916), 214–26. P.-G. Roy, Inv. concessions, I, 138f.; II, 168f.; IV, 195–97, 216f., 220f.; Inv. ord. int., I, 66, 106, 137, 192, 203, 248; Les officiers d’état-major, 209–13. Tanguay, Dictionnaire, I, 183; III, 351. Fauteux, Essai sur l’industrie sous le régime français. P.-G. Roy, La famille de Ramezay (Lévis, 1910). Guy Frégault, “Politique et politiciens au début du XVIIIe siècle,” Écrits du Canada français (Montréal), XI (1961), 91–208. Désiré Girouard, “Les anciens postes du lac Saint-Louis,” BRH, I (1895), 165–69. É.-Z. Massicotte, “Une femme d’affaires du régime français,” BRH, XXXVII (1931), 530; “Une soirée chez M. de Ramesay, gouverneur de Montréal, en 1704,” BRH, XXII (1916), 252f. Victor Morin, “Les Ramesay et leur château,” Cahiers des Dix, III (1938), 9–72. P.-G. Roy, “Josué Boisberthelot de Beaucours,” BRH, X (1904), 301–9. Benjamin Sulte, “La Vérenderie avant ses voyages au Nord-Ouest,” BRH, XXI (1915), 97–111.

Cite This Article

Yves F. Zoltvany, “RAMEZAY, CLAUDE DE,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 2, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed April 25, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/ramezay_claude_de_2E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/ramezay_claude_de_2E.html |

| Author of Article: | Yves F. Zoltvany |

| Title of Article: | RAMEZAY, CLAUDE DE |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 2 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1969 |

| Year of revision: | 1982 |

| Access Date: | April 25, 2025 |