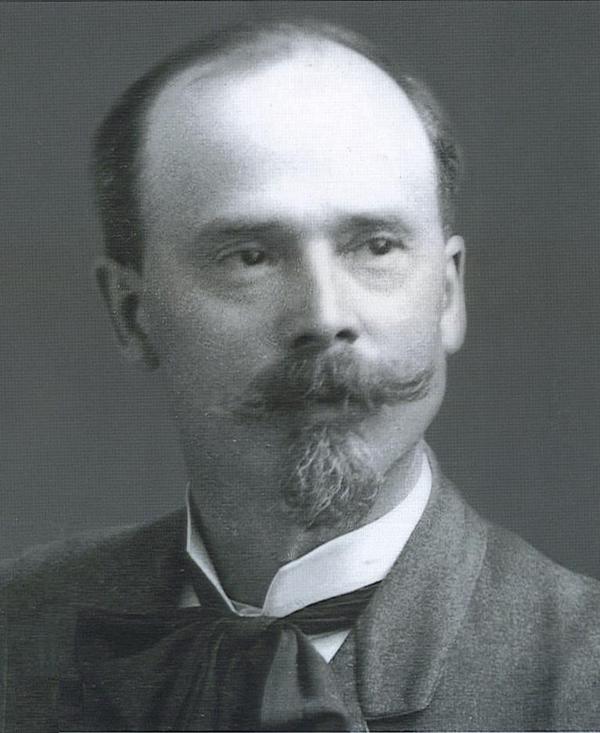

Source: Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

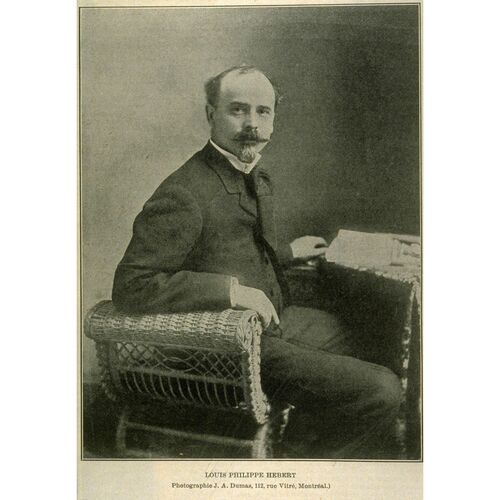

HÉBERT, LOUIS-PHILIPPE (he also signed Philippe), artist, sculptor, and teacher; b. 27 Jan. 1850 in Sainte-Sophie-d’Halifax (Sainte-Sophie-de-Mégantic), Lower Canada, third of the 13 children of Théophile Hébert, a farmer, and Julie Bourgeois; m. 26 May 1879 in Montreal Maria Roy, niece of architect Victor Roy, and they had eight children, including Henri*, a sculptor, and Adrien*, a painter; d. 13 June 1917 in Westmount, Que., and was buried 16 June in Notre-Dame-des-Neiges cemetery, Montreal.

Even as a child, Louis-Philippe Hébert had a passion for carving wooden horses and people drawn from his imagination. Between the ages of 6 and 13 he attended school off and on, and then he worked in turn at an uncle’s general store, on the family farm, and for the Grand Trunk Railway. In late September 1869 he left home and country and went to Rome with the fifth detachment of Papal Zouaves [see Édouard-André Barnard*; Ignace Bourget*]. He took advantage of his 11-month stay there to visit the museums, churches, and other points of interest “to be found wherever one goes in this city of the arts.” “Though the sight of all these marvels rekindled my longing for beauty [and] whetted my desire to become a sculptor, it often discouraged me,” he later noted in his autobiography. “All these beautiful works seemed to me like challenges flung at my feebleness.” On his return to Sainte-Sophie-d’Halifax in the autumn of 1870, the young man tried his hand at farming, and then decided to go to the United States to learn English. Home again a few months later, he became a travelling salesman, but apparently with little success, since he soon went back to his parents’ farm.

During a brief stay at Bécancour in 1872 or 1873, Hébert learned the rudiments of wood-carving from Adolphe Rho*, “an honourable man, clever, highly skilled, [but] unfortunately uneducated and not well connected,” as Hébert, who “set his sights higher,” recalled. For his true artistic apprenticeship, he would be indebted to Napoléon Bourassa, one of the most versatile and prominent Montreal artists of his time. At the provincial exhibition held in the city during the autumn of 1873 Bourassa noticed a small bust Hébert had done, and he decided to take him on as an apprentice, “to make him into a Phidias in flesh and blood.” Hébert spent six years with Bourassa, devoting the first few mainly to learning to draw and model in the master’s studio on Rue Sainte-Julie and at the school sponsored by the Council of Arts and Manufactures of the Province of Quebec. In the autumn of 1875 he was assigned to teach a course in freehand drawing at the school. At this time work also began, based on Bourassa’s plans and under his direction, on the interior decor for the chapel of Notre-Dame-de-Lourdes in Montreal, with which Hébert would be closely associated. As early as the spring of 1876 he advertised in the press as an “artist, sculptor, [and] illustrator, making statues, original busts, [and] portraits in pencil.” In the spring of 1879 he and Bourassa worked together on a model for a monument to Paul de Chomedey* de Maisonneuve.

Following a brief visit to the United States in search of contracts, Hébert went into business on his own late in the summer of 1879. For a few years he would share a studio with Bourassa. Late 1879 marked the beginning of his fruitful collaboration with Georges Bouillon*, an architect and priest who would commission him to do some 60 works in wood for decorating the chancel of Notre-Dame Cathedral in Ottawa. Olindo Gratton* and Philippe Laperle, carvers who joined Hébert’s studio in 1881 and 1882 respectively, would work closely with him on this impressive collection, for which he would receive the final payment in February 1887.

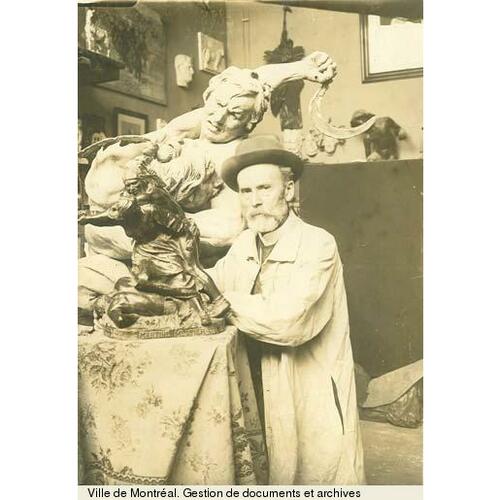

The year 1880 proved particularly important in Hébert’s career. Not only was he made an associate member of the new Royal Canadian Academy of Arts [see John George Edward Henry Douglas Sutherland Campbell; Lucius Richard O’Brien*], but he also received his first commission for a commemorative monument in bronze. His memorial to Charles-Michel d’Irumberry* de Salaberry was unveiled in Châteauguay on 7 June 1881. In describing the ceremony, the Montreal newspaper La Minerve noted, “This is the first time a statue representing someone of purely Canadian fame is being erected in a public place, and all with the aid of a nationally subscribed fund.” In 1882 the Canadian government announced an international competition for a memorial to Sir George-Étienne Cartier*, the first monument for Parliament Hill in Ottawa. At least a score of artists from Canada, the United States, and Europe sent models, and Hébert’s was selected. The unveiling of this statue in January 1885 was followed by the display in September of one of Mgr Joseph-David Déziel*, which Hébert had been commissioned to do by a committee of citizens from Lévis. Along with these pieces, he had been working since 1883 on the pulpit of Notre-Dame church in Montreal. This imposing work, which would occupy him until 1887, must be considered the pinnacle of his career as a woodcarver. In May 1884 Le Monde illustré (Montréal) declared that Hébert’s “workshop is too small, and four years would be scarcely enough time for him to complete all the orders he has at the moment.” It was in this period that he had a studio built at 34 Rue Labelle, where he would work from then on. In addition to all these activities, in 1882 Hébert had resumed teaching his classes for the Council of Arts and Manufactures, and he would intermittently give lessons there in anatomy, modelling, and woodcarving until near the end of the century. He became vice-president of the council in 1898.

A turning-point in Hébert’s career came in 1886. In the wake of a program established jointly by architect Eugène-Étienne Taché and Bourassa, Hébert offered to “undertake the task of composing, modelling, and casting in bronze the statues planned for the decoration of the new legislative building of this province.” He was commissioned to create ten of them. However, it was agreed that “in order to be able to obtain all the information he would require for the faithful and conscientious completion of his work, and also in order to have the benefit of consulting and observing the work of the great sculptors who honour [the] former mother country with their talent,” Hébert was to have “at least an 18-month sojourn in Paris.” Consequently he left Canada for France on 21 Feb. 1887. On his return to Montreal in July, he was immediately invited to display in the provincial exhibition at Quebec “the models for statues” which he had done in Paris. Bourassa, who saw the pieces, was disappointed with his protégé’s work and persuaded the authorities to let Hébert spend another three years in France, “to acquire the knowledge and taste necessary for the production of outstanding works.” After Hébert left with his family in the spring of 1888, the studio’s other commissions would be carried out by Gratton and Laperle, who also oversaw the work on the monument to Édouard-Joseph Crevier in Marieville (1888), among others.

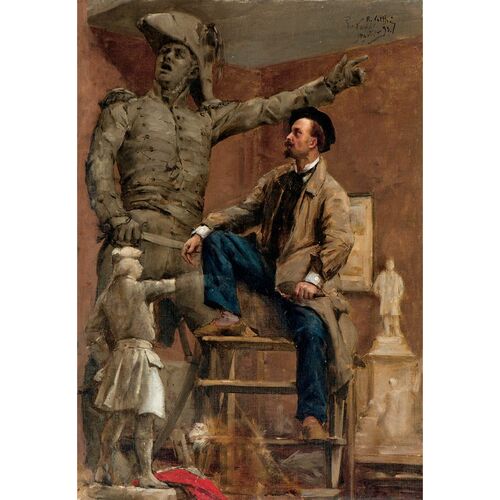

Upon reaching Paris, the Héberts settled in Montparnasse, where a large number of artists had studios. Among them were the sculptors Fréderic-Auguste Bartholdi, Jules Dalou, and Auguste Paris, who would become Hébert’s friends. He would also establish close ties with Canadians who visited Paris during those years. It was really in the French capital that he honed his skills as a modeller and became familiar with the complex techniques involved in casting bronze, especially in the work commissioned for the Quebec legislative building. Hébert first completed the piece for the entrance, a group of native people known as Famille d’Abénaquis or Halte dans la forêt. It was submitted to the universal exposition in Paris in 1889 and won him the third-prize medal of honour, a first for a Canadian artist. Cast in bronze, the sculpture was put on show at the exhibition of the Société des Artistes Français and arrived at Quebec in August 1890. The following year the bronze version of the Pêcheur à la nigogue (a man with a spear, standing on a rock), to be installed at the fountain, was displayed at the famous Paris Salon, to which Hébert sent pieces every year until he left in 1894; that year he presented his figures of Salaberry and François de Lévis* to the public. These two sculptures would be put in place on the façade of the legislative building in September and November respectively, joining the ones of Frontenac [Buade*] (installed in September 1890), Lord Elgin [Bruce*] (February 1892), and Montcalm* and Wolfe* (both May 1894). The two allegorical groups, Poésie et histoire and Religion et patrie, crowning the projecting part of the building’s left and right wings were also completed and cast in Paris during the same period, as were the monument, unveiled at Quebec in November 1891, to Charles John Short and George Wallick, who had died heroically in the Saint-Sauveur fire of 1889, and those to Maisonneuve, sent to Montreal in September 1893 and considered Hébert’s masterpiece, and to Sir John A. Macdonald*, the model for which was displayed in his Paris studio in June 1894. By the time Hébert moved back to Montreal with his family in October 1894, he had spent more than six years in Paris, except for short business trips to Canada in September and October 1890, May and June 1892, and February 1894. In his autobiography he described these as the best years of his life and the most beneficial for his career.

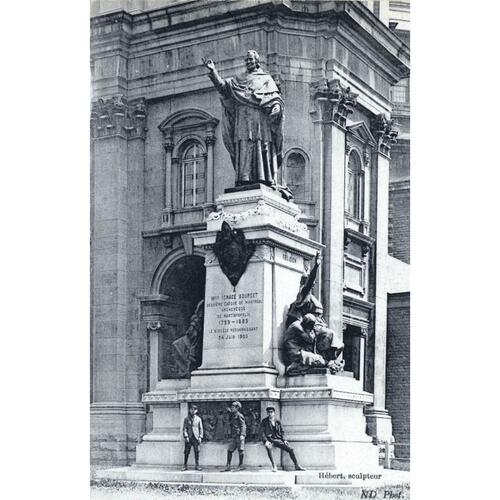

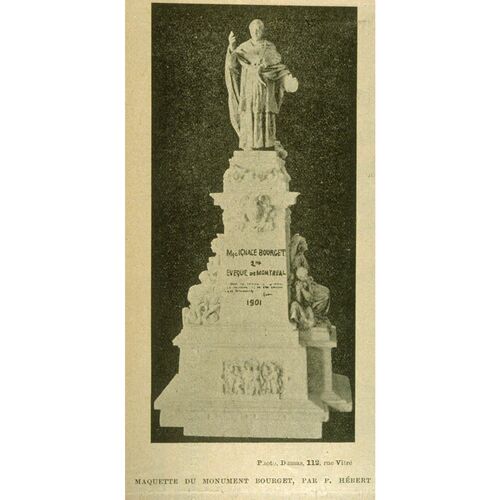

Apart from the delivery of the huge bronze angel for the Valois family monument in Notre-Dame-des-Neiges cemetery in Montreal, 1895 was noteworthy mainly for the unveiling in July of the monuments to Maisonneuve in that city and to Macdonald in Ottawa. The year 1896 is memorable for the monument to Father André-Marie Garin in Lowell, Mass., and the bronze bust of Louis-Adélard Senécal* that surmounts his tomb in Notre-Dame-des-Neiges cemetery. Several more of Hébert’s busts are to be found in that cemetery, including Cartier (1888), Charles-Séraphin Rodier* (1891), and Guillaume-Alphonse Nantel* (1894). In 1898 Hébert undertook to carve a St Philomena in wood for presentation to the convent in Hochelaga that was run by the Sisters of the Holy Names of Jesus and Mary. Fortune smiled on him again a little later in the year; he signed contracts in October and November for the statues of Queen Victoria and Alexander Mackenzie* to be erected on Parliament Hill. For the latter, in order to spare sensitivities, the contract was signed jointly with the English Canadian sculptor Hamilton Thomas Carleton Plantagenet MacCarthy, although in fact Hébert alone executed the work, which would be finished late in 1899. To carry out this twofold commission, Hébert returned to Paris, where both statues were shown at the universal exposition in 1900. During the family’s second stay in the French capital, which would last until October 1902, he also produced the memorial to Bishop Bourget that was commissioned by Archbishop Paul Bruchési* of Montreal.

It was at his Montreal studio that Hébert worked in February 1903 on the models for the figures of Octave Crémazie*, which would be unveiled on 24 June 1906 on Square Saint-Louis, and of Joseph Howe*, which was put on display in Halifax on 13 Dec. 1904. As for the one to the memory of Bishop François de Laval*, commissioned from Hébert in March 1905 for the tercentenary of Quebec City, the contract required him to “create his plaster model, or maquette,” in Paris. In addition, he had to “provide a certificate from three sculptors in Paris giving their approval of his model.” In June 1906, a few months before leaving for France, Hébert had the good fortune to sign a contract for a new monument to Queen Victoria, this one for Hamilton, Ont. During 1908, 1909, and 1910, he seemed to have entered a calmer period in his career, but it was during this time that he completed a number of works: the memorial to Charles-Théodore Viau* in Notre-Dame-des-Neiges cemetery (1908) and the statues of Jeanne Mance* at the Hôtel-Dieu in Montreal (1908), Pierre-Marie Mignault* in Chambly (1909), Sir Samuel Leonard Tilley* in Saint John, N.B. (1910), and Pierre Legardeur* de Repentigny in Saint-Henri-de-Mascouche (Mascouche) (1910).

In 1911 and 1912 Hébert was awarded three large contracts for public monuments that crowned his brilliant career. The work enabled him to go to Paris with his family late in 1911 for a final sojourn, which would conclude in the spring of 1914 with a visit to Italy. Early in 1911 he signed a contract for the South African War memorial in Calgary, the only equestrian work he had ever done (unveiled in June 1914). Towards the end of 1911 he received a commission for his most imposing work, the memorial to Marie-Madeleine Jarret* de Verchères (unveiled in Verchères on 21 Sept. 1913); the heroine, cast in bronze, stands more than 20 feet high. In July 1912 he had the pleasure of seeing his proposal for a monument to King Edward VII chosen over those of George William Hill*, Alfred Laliberté*, and Cœur-de-Lion MacCarthy, three sculptors who, with his son Henri, were gradually taking over the field of commemorative pieces. It was to Henri, doubtless for lack of time, that he entrusted the task of executing the figure of Camille Lefebvre* for Moncton, N.B., in 1913. On 1 Oct. 1914, following the unveiling of the statue of Edward VII by the governor general of Canada at Carré Phillips in Montreal, with a huge crowd in attendance, Hébert noted in his diary, “This monument is the largest and last work I have done.” From that day, in fact, he reduced his pace considerably. He died of throat cancer on 13 June 1917 at the age of 67.

In addition to the 50 or so commemorative and cemetery monuments that mark Hébert’s career, his life work includes a large number of statuettes, busts, medallions, and medals depicting both historical figures and his contemporaries – politicians, authors, wealthy financiers, clergy, and close friends. He was also recognized for his groups illustrating episodes from the heroic beginnings of Canada’s history, such as his famous Sans merci, displayed at the universal exposition in Paris in 1900. Hébert’s statuettes, often cast in bronze with many copies and depicting charming female figures, such as Fleur des bois (1897) and Soupir du lac (1903), exactly matched the tastes of the period and also enhanced his fame. His renown would be acknowledged over the years by various awards. Ottawa presented him with the Confederation Medal in 1894, Paris made him a knight of the Legion of Honour in 1901, in London he was created a cmg in 1903, and in Rome he became a knight of the Order of St Gregory the Great in 1914. Hébert was extremely eager to have his works reach a wide public and took every opportunity to put his most recent piece on display. Although at the outset of his career he was content to use store windows for this purpose, from 1880 his association with the Royal Canadian Academy of Arts enabled him to exhibit at the most important museums in Ottawa, Montreal, and Toronto. From 1895 his works were regularly shown at the spring exhibitions of the Art Association of Montreal also. He participated in a number of world fairs and international exhibitions, in Philadelphia (1876), Boston (1883), Antwerp (1885), Paris (1889 and 1900), and Glasgow (1901).

The best-known likeness of Hébert is probably the portrait done by painter Joseph Saint-Charles when his model was about 50 years old. This canvas, held at the Musée du Québec, leaves no room for doubt that Hébert took meticulous care of his appearance. The many extant photographs give an occasional hint of self-importance. A journalist who visited Hébert’s studio in 1910 noted that he “takes an ingenious and candid delight in talking about himself.” Hébert’s contemporaries agree, however, in recognizing that he had the finest of qualities. He was “the most charming fellow in the world,” remarked sculptor Lauréat Vallière. “Tall, educated, astute, a good conversationalist, he was likeable on first acquaintance.” For Edmond Dyonnet, he was “a tireless worker taking pleasure in his work.” In the same vein, Alfred Laliberté acknowledged him to be “a great worker and nobody’s fool, who had acquired these qualities through contact with the artists and writers who were his friends.” His circle included painters Marc-Aurèle de Foy Suzor-Côté*, Henri Julien*, and Maurice Galbraith Cullen*, as well as writers Ernest Gagnon, Benjamin Sulte*, and Louis Fréchette*. It is clear that Hébert was a loyal friend, a respectful son, an obliging brother, an affectionate husband, and an attentive father to his children, qualities transparent in his correspondence.

On his death Louis-Philippe Hébert left a fortune estimated at nearly $100,000. The modest beginnings of the sculptor who, like Louis Jobin*, earned his living for a long time by decorating churches, had been largely forgotten. “Philippe Hébert was the great illustrator of our history,” observed Le Devoir on 14 June 1917. “His work is a heroic and timeless commentary on it.” On the same day La Presse declared, “His monuments live on after him and will recall to future generations the memory of this honest citizen and artist of whom we have the right to be proud.” Indeed, if Hébert is remembered, it is because he was “the first Canadian sculptor of commemorative statues.” The artist “had the luck to have talent, but he also had a talent for having good luck,” notes his biographer Bruno Hébert. “Whenever opportunity arose, he was ready. In a few years of hard work he managed to assimilate the essence of the European tradition in sculpture. He imported into Canada an art until then reserved for the Old World. In this sense, he created . . . something new and also ushered in an important stage in the history of art in Canada.” Canadian sculpture is indebted to Hébert, who brought it into the modern era. He blazed the trail for a new generation who would abandon wood for bronze, just as they would desert the churches for public squares and museums.

[This biography is based on material collected by the author over the course of several years’ preparatory work for a Louis-Philippe Hébert retrospective which is to appear at the Musée du Québec (Québec) in the summer of 1999 and at the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts in the autumn. The research is not yet complete. A comprehensive bibliography on Hébert will appear in the exhibition catalogue, which will be published jointly by the two museums in 1999.

Hébert retained during his lifetime most of the papers concerning his life and career. This material is preserved in several locations: the Hébert fonds at the Musée du Québec (H1990), which includes his correspondence for 1870–1917, a list of his works, and his will; the Hébert fonds at the Bibliothèque de la Ville de Montréal, Salle Gagnon, which contains his correspondence for 1900–8 and his diary for 2 oct. 1886–31 déc. 1901; and the collections of two of the artist’s descendants. Papers held by Bruno Hébert of Joliette, Que., include a notebook, c. 1873–79, and a diary. Material in the possession of Angèle Hébert-Coulombe of Saint-Jean-sur-Richelieu, Que., includes contracts, financial documents, and a typescript copy of Hébert’s autobiography, “Étapes de ma vie,” which was published under that title by Bruno Hébert in Les Cahiers de Cap-Rouge (Cap-Rouge, Qué.), 8 (1980), no.1: 16–55. Hébert’s marriage certificate is found in ANQ-M, CE1-33, 26 mai 1879.

Among the more than 40 journals and newspapers in which information on Hébert has been found (mainly published in Quebec, but also from Ontario, New Brunswick, London, and Paris), the following contain the most frequent references: Le Courrier de Saint-Hyacinthe (Saint-Hyacinthe, Qué.), 1879–1900; Le Courrier du Canada (Québec), 1881–1900; L’Électeur (Québec), 1881–96; La Minerve, 1875–98; Le Monde illustré (Montréal), 1884–1901; the Montreal Daily Star, 1881–1906; L’Opinion publique (Montréal), 1875–83; Paris-Canada (Paris), 1885–1907; La Patrie, 1892–1913; and La Presse, 1887–1917. y.l.]

Sylvain Allaire, “Les artistes canadiens aux salons de Paris, de 1870 à 1914 (salons des artistes vivants – des artistes français, salons de la nationale des beaux-arts, salons des artistes indépendants, salons d’automne)” (mémoire de ma, univ. de Montréal, 1985). N[apoléon] Bourassa, Lettres d’un artiste canadien: N. Bourassa, Adine Bourassa, édit. (Bruges, Belgique, et Paris, 1929). F.-L. Desaulniers, Les vieilles familles d’Yamachiche (4v., Montréal, 1898–1908), 4: 77–78. A dictionary of Canadian artists, comp. C. S. MacDonald (7v. to date, Ottawa, 1967– ), 2. Directory, Montreal, 1876–1917. Edmond Dyonnet, Mémoires d’un artiste canadien, préface de Jean Ménard (Ottawa, 1968). Romain Gour, Philippe Hébert, sculpteur et statuaire (Montréal, 1953). [T. G. Guernsey], Statues of Parliament Hill; an illustrated history (Ottawa and Hull, Que., 1986). Bruno Hébert, “Hommage à Philippe Hébert,” Les Cahiers de Cap-Rouge, 8, no.1: 7–15; Philippe Hébert, sculpteur (Montréal, 1973). Karel, Dict. des artistes. Alfred Laliberté, Les artistes de mon temps, Odette Legendre, édit. (Montréal, 1986). Bernard Mulaire, Olindo Gratton, 1855–1941; religion et sculpture (Montréal, 1989); “Olindo Gratton et Louis-Philippe Hébert: une relation professionnelle entre deux sculpteurs à la fin du XIXe siècle,” Journal of Canadian Art Hist. (Montreal), 12 (1989): 22–47. Le Musée du Québec: 500 œuvres choisies (Québec, 1983). [Luc Noppen et Gaston Deschênes], L’Hôtel du Parlement, témoin de notre histoire (Québec, 1986). Normand Pagé, La cathédrale Notre-Dame d’Ottawa; histoire, architecture, iconographie (Ottawa, 1988). Souvenir de Maisonneuve: esquisse historique de la ville de Montréal . . . (Montréal, [1894?]).

Cite This Article

Yves Lacasse, “HÉBERT, LOUIS-PHILIPPE (Philippe),” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 14, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed February 21, 2026, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/hebert_louis_philippe_14E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/hebert_louis_philippe_14E.html |

| Author of Article: | Yves Lacasse |

| Title of Article: | HÉBERT, LOUIS-PHILIPPE (Philippe) |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 14 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1998 |

| Year of revision: | 1998 |

| Access Date: | February 21, 2026 |