Source: Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

CLOSSE, RAPHAËL-LAMBERT (often referred to simply as Lambert), merchant, seigneurial notary, sergeant-major of the Ville-Marie garrison, acting governor of Montreal; b. c. 1618 at Saint-Denis de Mogues, in the Ardennes, son of Jean Closse and Cécile Delafosse; m. Élisabeth Moyen in 1657; killed 6 Feb. 1662 at Montreal and buried there the following day.

We have no information concerning Lambert Closse’s youth, and no details about his family. He certainly received a good education; in the light of the affection that the missionaries in Canada had for him, it was perhaps from the Jesuits. On occasion they wrote to him quite confidentially. We can also assume that his military career began fairly early. He acquired a sound knowledge and much experience in his profession. The authority that M. de Chomedey de Maisonneuve gave him over the soldiers of the garrison in the fort, and his title of sergeant-major, which he held until his death, help to explain why François Dollier* de Casson constantly praised his valour.

It is difficult to determine exactly the date of Closse’s arrival in the settlement. M. Massicotte, making his deduction from a notarial document that Closse signed on 2 May in the office of Jean de Saint-Père, refers to his presence at Ville-Marie in 1648. He must have arrived a year earlier with the contingent that M. de Maisonneuve had brought from France. Besides, M. Massicotte mentions no new settler in that year, 1648. A passage written by Sister Marie Morin* cannot but leave the historian puzzled: “Monsieur de Chomedey, who sought only to glorify God and to work for his own sanctification and that of the persons whom God had associated with him in his task, applied himself to establishing several little practices of virtue and devotion, of a simple and humble nature, to which he referred everything; he set up a fraternity of five brothers and five sisters; he was the first of the brothers, followed by Monsieur Lambert Closse, Monsieur Lucau, Monsieur Minime Barbier, Monsieur Prudhomme; the sisters were Madame d’Alleboust, Madame de La Peltrie, Mademoiselle Mance, Mademoiselle de Boulogne, Mademoiselle [Charlotte Barré] who was as I said Madame de La Peltrie’s lady companion; they called each other only brothers and sisters, made a point of deferring to each other in everything, of serving all people when they were in need, of consoling them, of serving the sick, &c.; they made many novenas and pilgrimages to the mountain, on foot, and at the risk of their lives because of the Iroquois.”

The presence at Ville-Marie of certain of the settlers mentioned above gives us the date of these pious journeyings. Mme d’Ailleboust [see Boullongne] and her sister arrived at Ville-Marie only in September 1643; Mme de Chauvigny de La Peltrie and her attendant, Charlotte Barré, had already returned to Quebec in the summer of 1644. Therefore, from September 1643 to May 1644, out of the 10 people indicated by Sister Morin, eight were living at Ville-Marie beyond all question. There remain Lambert Closse and Louis Prud’homme, whose presence at Montreal in 1643 must be proved. All that one can say is that they might have formed part of the contingent of 40 settlers brought to Canada that year by Louis d’Ailleboust.

M. Massicotte lists the titles and functions of Lambert Closse as follows: sergeant-major, merchant, notary. If this professional soldier carried on business, what was its nature? A solitary document throws a little light on the question: the inventory of Lambert Closse’s personal possessions and real estate, drawn up in 1662 by the notary Bénigne Basset, indicates that the sergeant-major of Ville-Marie traded in furs with the Indians, like all his contemporaries. P.-G. Roy offers the following explanation in this connection: “Some who are unfamiliar with the habits and customs of the age when Closse lived have been almost scandalized on reading this document. How, said these scrupulous people, could a hero like Lambert Closse take part in the fur trade? Well, yes, Closse did trade in furs like all his contemporaries. Officials and even religious communities did so in that period. It must be admitted that this fraudulent system was allowed and encouraged by the king. He paid starvation wages to his officers, to his judges, to all those whom he employed, and in order not to die of hunger they were forced to do fur-trading. Some did it discreetly and honestly, others used every means to swell their nest-egg. . . . Closse’s inventory . . . gives us an almost complete list of all the objects used for the fur trade.”

Jean de Saint-Père and Lambert Closse, the first two scriveners [tabellions] of Montreal, must have been the same age according to M. Massicotte. In any case, they practised their profession alternately. The first document from the office of Jean de Saint-Père was dated 4 Jan. 1648, and that from the registry of Lambert Closse 6 July 1651. Closse’s file is composed of 30 documents, from 1651 to 1656; 16 are in the hand of M. de Maisonneuve, 6 are written by an unknown copyist, and the rest by M. Closse. M. Massicotte points out: “M. Closse’s script fairly closely resembles that of M. de Saint-Père; it differs from it by some spelling mistakes peculiar to our soldier, and by the handwriting which is lighter and more tapering.”

Nobody can deny to Lambert Closse the title of saviour of Montreal during the years when the Iroquois terror paralysed all progress and decimated the population. In 1651, “only about fifty French remain there,” said the Relations. In such tragic circumstances, Lambert Closse showed himself a leader of heroic calibre, with unfaltering will-power, a man whose qualities were exalted by the greatest perils instead of being weakened, and who knew how to keep his soldiers screwed to a pitch of valour that made the slightest action effective.

The writings of the time are unanimous in their praise, gratitude, and admiration. Long and circumstantial accounts prove the truth of this; in them stirs an enthusiasm that we still sense today. The Jesuits, Dollier de Casson, Marie de l’Incarnation [see Guyart], Marguerite Bourgeoys, Sister Morin, Mother Juchereau* de Saint-Ignace – all have immortalized in their narratives the exploits and the name of Lambert Closse.

Dramatic circumstances surrounded the marriage of Lambert Closse, who was 39, and Élisabeth Moyen, who was 16. In 1655, when Élisabeth was living with her parents on Île aux Oies, below Quebec, a party of Iroquois suddenly appeared. Her father and mother, Jean-Baptiste Moyen Des Granges and Élisabeth Le Bret, were slaughtered on the spot; Élisabeth and her sister Marie were taken as captives to an Onondaga village. This story soon became known at Ville-Marie. The Montrealers, who were battling unceasingly with the Iroquois bands, then kept a close watch on their enemies. They hoped to discover some day the murderers of the Moyen family; this did happen in fact when Charles Le Moyne returned from Quebec, for he recognized some of them. Dollier de Casson has told of the vicissitudes of the struggle that immediately began, and in which the artfulness and guile of Charles Le Moyne, the foresight of Maisonneuve, and the bravery of Lambert Closse and his soldiers brought about victory. This was followed by the exchange of several Iroquois chieftains being held in the fort for all the French prisoners in the hands of the Onondagas. Thus the young Moyen girls, half dead with fear and grief, reached Ville-Marie. Jeanne Mance received them at her Hôtel-Dieu, and under her care they gradually recovered.

In the autumn of that same year 1655, MM. de Maisonneuve and Louis d’Ailleboust left Ville-Marie for France. In M. de Maisonneuve’s absence it was Lambert Closse who was in command at Ville-Marie. It is to be supposed that the acting governor paid many visits to the Hôtel-Dieu, for Jeanne Mance, with her judgement and her peculiar power of foreseeing difficulties and often of solving them, was a counsellor esteemed by all. Lambert Closse then had the opportunity of seeing Élisabeth Moyen and of chatting with her. The latter’s feelings of gratitude towards one of her deliverers were gradually transformed into affection. On 12 Aug. 1657 the marriage of Lambert Closse and Élisabeth Moyen was celebrated by the Jesuit Father Claude Pijart in the parish of Notre-Dame de Montréal.

M. de Maisonneuve returned to Canada on 29 July 1657, together with Louis d’Ailleboust and four Sulpicians. The governor’s return gave Lambert Closse a little more freedom. He hastened to instal his young wife as comfortably as possible. He owned a property of 30 acres, which he had acquired 10 March 1652. The deed of sale was signed before Nicolas Gastineau Duplessis. Six months after his marriage, that is 2 Feb. 1658, Lambert Closse was granted by M. de Maisonneuve, as a fief, “100 arpents, beginning 10 rods from the big river, by 40 rods wide.” This fief began at the rue Saint-Laurent, and it is in honour of Lambert Closse that the côte Saint-Lambert bears that name.

Two children were born to the Closse family. The elder, Élisabeth, born early in October 1658, died the same day; the younger, Jeanne-Cécile, born 1660, had Jeanne Mance as her godmother. In 1678 she married Jacques Bizard, the town-major of Montreal and the seigneur of Île Major (Bizard), who died in 1692. Jeanne-Cécile remarried in 1694; her second husband was Raymond Blaise* Des Bergères de Rigauville.

Lambert Closse disappeared in 1662, “killed by a band of Iroquois when he was going to aid some Frenchmen in danger.” This “brave Mons. Closse,” wrote Dollier de Casson, “. . . died like a brave soldier of Jesus Christ and of our Monarch, after having a thousand times exposed his life most courageously, without fearing to lose it on such occasions, which he clearly stated to some who said to him shortly before his death, ‘that he would get himself killed because of the readiness with which he exposed himself everywhere in the service of the country,’ – to this he replied – ‘Gentlemen, I came here only in order to die for the sake of God while serving him in the profession of arms; if I did not think to die here I would leave the country to go and serve against the Turks and not be deprived of that glory.’”

The Relation of 1662, for the edification of posterity, also published the hero’s funeral eulogy: “He was a man whose piety was no whit inferior to his valour, and who possessed extraordinary presence of mind in the heat of battle . . . and justly won the credit of saving Montreal, both by his might and by his reputation. Hence it was deemed advisable to keep his death concealed from the enemy, for fear that they might take advantage of it. This Eulogy we owed his Memory, since Montreal owes him its life.”

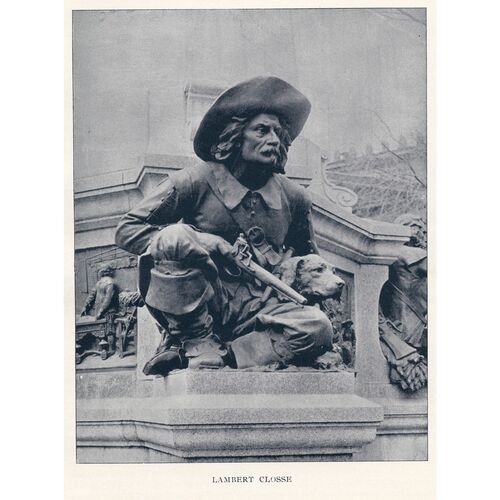

We know of no authentic picture of the town-major of Ville-Marie. An imaginary representation of Lambert Closse has been made by the sculptor Louis-Philippe Hébert*, and forms part of Maisonneuve’s monument in Montreal.

AJM, Greffe de Bénigne Basset, 22 nov. 1659, 8, 20 févr. 1662, 1er, 27 févr. 1667; Greffe de Lambert Closse, 1651–56; Greffe de Jean de Saint-Père, 1648–51, 1655–57, passim. AJTR, Greffe de Nicolas Gastineau, 10 mars 1652. Dollier de Casson, Histoire du Montréal. JR (Thwaites). JJ (Laverdière et Casgrain). Morin, Annales (Fauteux et al.). Premier registre de l’église Notre-Dame de Montréal (Montréal, 1961).

Aristide Beaugrand-Champagne, “Les origines de Montréal,” Cahiers des Dix, XIII (1948), 57. Faillon, Histoire de la colonie française. É.-Z. Massicotte, “Les actes des trois premiers tabellions de Montréal, 1648–1657,” RSCT, 3d ser., IX (1915), sect.i, 189–204; “Les colons de Montréal de 1642 à 1667,” ibid., 3d ser., VII (1913), sect.i, 3–65, and BRH, XXXIII (1927), 238ff.; “L’inventaire des biens de Lambert Closse,” BRH, XXV (1919), 16–31; “Memento historique de Montréal, 1636–1760,” RSCT, 3d ser., XXVII (1933), sect.i, 111–31 ; “Les premières concessions de terre à Montréal, sous M. de Maisonneuve, 1648–1665,” ibid., 3d ser., VIII (1914), sect.i, 215–29. P.-G. Roy, Toutes petites choses du régime français (2v., Québec, 1944), I, 69–73. Félicité Angers [Laure Conan], L’oublié (Montréal, 1900). [This historical novel, which the author has considered as fictional biography because of its fidelity to the facts and its truthful depiction of personality, is of classical stature. The clearly delineated characters are in striking relief, so that the work resembles a fresco in which the figures possess an intense life. m.-c. d.]

Revisions based on:

Bibliothèque et Arch. Nationales du Québec, Centre d’arch. de Montréal, CE601-S51, 12 août 1657, 7 févr. 1662; CN601-S92, 13 févr. 1654.

Cite This Article

Marie-Claire Daveluy, “CLOSSE, RAPHAËL-LAMBERT (Lambert),” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 1, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed December 29, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/closse_raphael_lambert_1E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/closse_raphael_lambert_1E.html |

| Author of Article: | Marie-Claire Daveluy |

| Title of Article: | CLOSSE, RAPHAËL-LAMBERT (Lambert) |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 1 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1966 |

| Year of revision: | 2015 |

| Access Date: | December 29, 2025 |