Source: Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

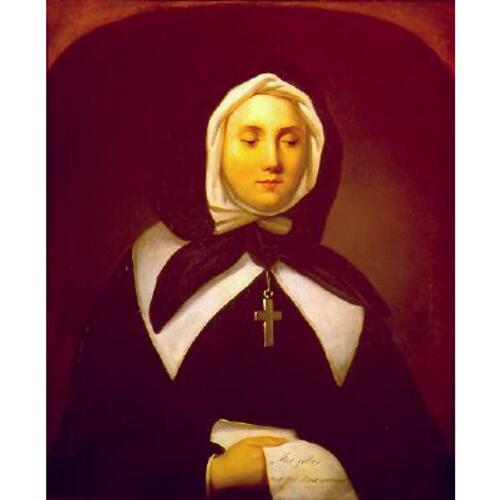

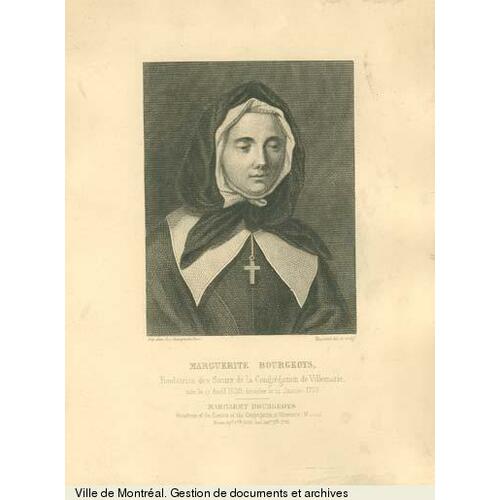

BOURGEOYS, MARGUERITE, dite du Saint-Sacrement, founder of the Congrégation de Notre-Dame de Montréal; b. 17 April 1620 at Troyes in Champagne (France); d. 12 Jan. 1700 at Montreal and was buried there the next day; beatified 12 Nov. 1950 and canonized 31 Oct. 1982.

Marguerite Bourgeoys was born in France in the century of the Thirty Years’ War and the Fronde, during the period of the mighty triumphs of organization achieved by Richelieu and Colbert, during the period of the great mystics of the French school: Jean-Jacques Olier, Pierre de Bérulle, Charles de Condren. She was marked by her environment and by her time, and was destined to be both a great realist and a profound mystic, and also to assume the figure of a forerunner.

By her father, a master candle-maker and a coiner in the mint at Troyes, as well as by her mother Guillemette Garnier, Marguerite belonged to the 17th-century French bourgeoisie. The detailed inventory of Mme Bourgeoys’s estates and jewellery, and an examination of the Garnier family, give proof of the high quality of the social relations maintained by the parents and of the comfortable circumstances in which they lived.

Up to 1950 the biographers of Marguerite Bourgeoys continued to assert that she became an orphan at the age of 12, and that from that time on she was responsible for keeping house and for the education of her brothers and sisters. Documents discovered since prove, on the contrary, that Marguerite, the sixth of the 12 Bourgeoys children, was 19 at her mother’s death, and that an elder sister, Anne, was still at home in 1639. It was in 1640 – when Marguerite was 20 – that she passed the first milestone in the astonishing odyssey that was to bring her to New France.

The Congrégation de Notre-Dame, founded in 1598 by Alix Leclerc at the instigation of Abbé Pierre Fourier, had a convent at Troyes. These cloistered nuns, who could not go outside the monastery to exercise their calling, had recourse to a compromise: a so-called external congregation, that is, a group of girls who met in the monastery for religious instruction and lessons in pedagogy.

“Notwithstanding all the entreaties which had been made to her,” Marguerite Bourgeoys had always refused to enter the external congregation, lest she be “thought a bigot.” But in 1640, during the procession of the Rosary, a sudden unforeseen incident changed her destiny. She wrote: “We passed again in front of the portal of [the abbey of] Notre-Dame, where there was a stone image [of the Virgin] above the door. When I looked up and saw it I thought it was very beautiful, and at the same time I found myself so touched and so changed that I no longer knew myself, and on my return to the house everybody noticed the change, for I had been very light-hearted and well-liked by the other girls.”

Marguerite Bourgeoys’s first step was to enter the external congregation. The director of the congreganists was then Mother Louise de Chomedey de Sainte-Marie, sister of Paul de Chomedey de Maisonneuve, the governor of Ville-Marie (Montreal). Through her, Marguerite heard about Canada, and then was introduced to Maisonneuve, who was passing through Troyes in 1652. Sister Louise de Chomedey and a few associates begged Maisonneuve to take them to Montreal. But he refused, saying that under the conditions prevailing at the time a religious community would be unable to exist at Ville-Marie. Marguerite Bourgeoys, who was then 33, offered to go there, and Maisonneuve accepted her.

Having been inexplicably refused admission to the Carmelites and to some other orders, she was free to go to Ville-Marie. In February 1653 she left Troyes, and finally landed at Quebec, after many difficulties, on 22 September.

When she reached Ville-Marie, Marguerite Bourgeoys found there were no children of school age, because of the infant mortality: “For about eight years we were unable to find any children to raise.” Meanwhile, she acted like an older sister to the settlers. Already, on the boat, her presence had been a moral lesson for them, had in fact almost converted them, for on their arrival “they were changed like clothes that are put in the wash.” In 1657 she seems with her winning ways to have persuaded them to make up a work-party for the construction of the chapel of Notre-Dame-de-Bon-Secours (the first stone church built on the island of Montreal), which, despite many transformations, still stands today in the same spot. The testimony of her contemporaries affirms that people had recourse on every occasion to Marguerite, a real social worker before the invention of the term.

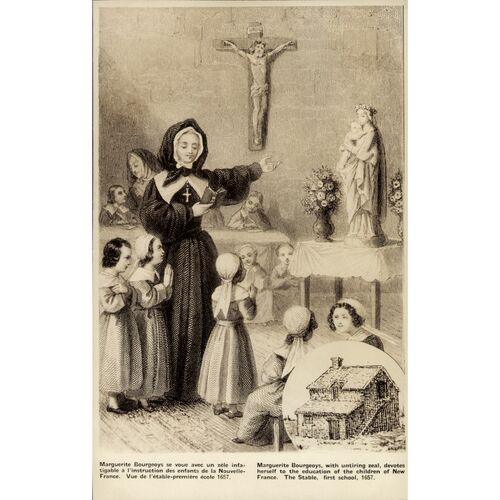

But the mission towards which her inclinations and her natural disposition urged her was teaching. On 30 April 1658 Marguerite Bourgeoys was finally able to receive her first pupils in a stable that had been given her by Maisonneuve for want of something better. The deed of grant stated that it was “a stone building 36 feet long by 18 wide, situated at Ville-Marie, near the Hôpital Saint-Joseph.”

Marguerite, however, had greater ambitions, for she returned to France that same year, 1658, “with the intention of bringing back some girls to help me to give lessons to the children.” She did bring back three worthy bourgeois girls, Edmée Châtel, Marie Raisin, and Anne Hiou, as well as a “sturdy wench” for the heavy jobs. Thanks to her companions’ help, Marguerite Bourgeoys was soon to be in a position to receive the filles du roi, the young orphan girls sent by Louis XIV to New France “to start families.” She went “to meet them at the shore,” and prepared them for their future role. It was to her house that the settlers of Ville-Marie came to seek a wife, and they had to undergo a rigorous examination. They seem moreover to have appreciated this unusual matrimonial agency, as well as the teaching given to the children at Marguerite Bourgeoys’s school, for in 1667, at a “settlers meeting,” they resolved to ask the king to grant letters patent to the “filles de la Congrégation,” the name by which “Sister Bourgeoys” and her companions were already known at Ville-Marie.

For his part, Bishop François de Laval*, the apostolic vicar of New France, at the time of his 1669 visit, gave his approval in the form of an ordinance authorizing the teachers of Ville-Marie to instruct on the Île de Montréal and in all other places in Canada that should ask for their services.

Marguerite Bourgeoys therefore decided, in 1670, to go and “ask the King for letters patent” in order to guarantee the existence of her community. This was perhaps the most astonishing of all her journeys. She set off, the only woman, with ten sols in her pocket. Reaching Paris, “without money, clothes or friends,” she made her way into the king’s presence. Jean Talon, in his report dated 10 Nov. 1670, had pointed out to Colbert the services rendered to Canada by this “kind of congregation formed to teach children not only reading and writing, but simple handiwork.” And Colbert had written in the margin: “This institution must be actively encouraged.” The ground was thus well prepared, and in May 1671 Marguerite Bourgeoys obtained from the king the desired letters patent. “Not only,” wrote the king, “has she performed the office of schoolmistress by giving free instruction to the young girls in all the occupations that make them capable of earning their livelihood, but, far from being a liability to the country, she has built permanent buildings, cleared land-concessions, set up a farm. . . .”

Marguerite Bourgeoys brought back from France three of her nieces: Marguerite, Catherine, and Louise Sommillard. Marguerite and Catherine were later to become sisters of the Congrégation, and Louise the wife of a settler named Fortin.

This period (1672) was for Marguerite Bourgeoys the beginning of the golden age of her work in New France, a decade of great expansion.

At the request of the noble and bourgeois families who had previously sent their daughters to Quebec, Marguerite Bourgeoys opened a boarding-school at Ville-Marie, in 1676.

But Marguerite Bourgeoys’s preferences went to young girls less favoured by fortune. For them she set up the first domestic training school in the country, the needle-work school (Ouvroir de la Providence), at Saint-Charles point. In addition she sent her assistants to all those who could not come to the boarding-school. Thus small schools were founded at Lachine, Pointe-aux-Trembles (Montreal), Batiscan, and Champlain. The little Indian girls were always special favourites of hers. From the time she came to Ville-Marie, Marguerite Bourgeoys had always attracted and welcomed a few to her school. Around 1678 she established a mission in the Indian village of Montagne. The sisters taught in cabins made of bark. It was only at the turn of the century that they were housed in the towers of the fort built by M. Vachon* de Belmont; these towers can still be seen today on the ground occupied by the Grand Séminaire of Montreal.

As she saw her work developing to an extent that had been unforeseeable at the beginning, Marguerite Bourgeoys became concerned about the future. Before sending them on a mission, she had indeed given her companions training in pedagogy, and especially in a rule of life that was suited to a secular community and that she had elaborated in imitation of Our Lady’s earthly existence. Already, it is true, Bishop Laval and Louis XIV had agreed that this type of life should be tried, and the settlers had long called them “sisters.” But Marguerite Bourgeoys and her companions could make only promises valid in civil law, since the official hierarchy of the Church had not approved a formal status for them.

For this reason Marguerite Bourgeoys undertook a third voyage to France in 1680, this time with Mme Perrot, the wife of François-Marie Perrot, the governor of Montreal. Bishop Laval, who was in Paris, overburdened with cares, received her coldly and even forbade her to attempt any recruiting.

This journey, however, was not useless. Marguerite Bourgeoys met Mme de Miramion, but lately a celebrity at the court, who was living in retirement and directing a group of young girls doing charitable works – a “mother of the church,” as Mme de Sévigné put it. Marguerite returned to Canada having acquired valuable experience of religious life in France and better prepared to face the difficulties which would soon beset her young community.

In December 1683 Sister Bourgeoys intended to resign and to proceed to the election of a new superior. But it so happened that during the night of 6 to 7 December a fire destroyed the mother house and caused the death of the two candidates for election, Marguerite Sommillard and Geneviève Durosoy.

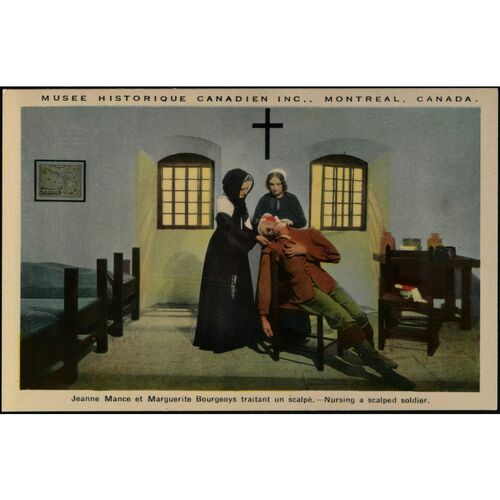

So Sister Bourgeoys courageously resumed office. The succeeding years recall those of the great foundations; it was the beginning of the Quebec era. In 1685 Bishop Saint-Vallier [La Croix*], who succeeded Bishop Laval, brought the sisters of the Congrégation to the parish of Sainte-Famille on the Île d’Orléans. Sister Mayrand and Sister Marie Barbier*, dite Marie de l’Assomption, were to be the heroines of this difficult foundation. A few months later the bishop, delighted with Sister Bourgeoys’s work at the Ouvroir de la Providence, decided to set up a similar charity school at Quebec. To this end he bought “a house near the great square of Notre-Dame, opposite the close of the reverend Jesuit Fathers,” and then he fetched from the Île d’Orléans Sister Barbier, who was soon joined by a companion from Montreal, Sister Marie-Catherine Charly*. It was in this same house of Providence that Bishop Saint-Vallier was to open his Hôpital Général in 1689, appointing two sisters of the Congrégation as nurses to take care of the aged.

In 1692 the whole organization of the Congrégation at Quebec was modified. At the request of the parish priest of Quebec and to Sister Bourgeoys’s delight, the sisters of the Congrégation opened a school for little girls from the poor families of the Lower Town.

As for the activities of the Hôpital Général, Bishop Saint-Vallier housed them in the former convent of the Recollets on the Saint-Charles River, and entrusted them thenceforth to the Hospitallers.

The resignation of Sister Bourgeoys was finally accepted at Montreal in 1693; Sister Barbier was elected superior general. Yet Marguerite Bourgeoys, at 73 years of age, was not yet to withdraw to the infirmary, there to enjoy the peace that comes from the completion of one’s labours. Bishop Saint-Vallier reopened the question of the essence and of the very existence of the Congrégation by trying to merge the sisters with the Ursulines, or to impose upon them the cloister and a rule of his own making. But finally, with the help of M. Tronson, the superior of the Sulpicians in Paris, and sustained by the lucid will of the founder, Sister Barbier succeeded in having this rule modified to fit the requirements “of secular nuns.” On 1 July 1698, the day preceding the Visitation, in the presence of Bishop Saint-Vallier, Marguerite and her companions took simple vows in the Congrégation de Notre-Dame, which was canonically constituted a community. Marguerite Bourgeoys was henceforth to be called “Sœur du Saint-Sacrement,” a name that sums up the last two years of her life, two years of solitude and prayer. From 1695 the mother house of the Congrégation finally had a chapel, thanks to the gifts made by Jeanne Le Ber*, who had asked in return to live there as a recluse for the rest of her life.

Marguerite Bourgeoys’s death, following the model of her life, was marked by realism and mysticism. Sister Catherine Charly was dying; to save this young nun’s life, Marguerite Bourgeoys offered her own: “Oh God,” she prayed, “why do you not take me instead, I who am useless and good for nought!” The evening of that very day, according to Glandelet, who cites letters from witnesses of the occurrence, Sister Charly was saved, and Sister Bourgeoys, who was well up to that time, was taken with a high fever. She died a few days later.

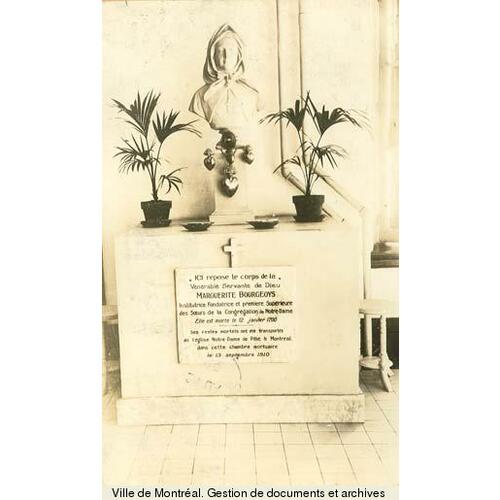

For forming an idea of Marguerite Bourgeoys’s stature in the eyes of her contemporaries, there is no more revealing source than their tributes of esteem and veneration at the time of her death. Popular admiration had already canonized her 250 years before her beatification; the objects which had been placed in contact with her hands, during the afternoon when the public was admitted to see the body lying in the chapel of the Congrégation, were considered relics. The unanimity of the praises addressed to her cannot be misleading. A further testimony of esteem was the discussion about the possession of her remains, which had moreover to be settled by a compromise; the parish of Ville-Marie kept her body and the Congrégation de Notre-Dame her heart.

Marguerite Bourgeoys’s pedagogy comprised the great principles of teaching used in 17th-century France, and more particularly those of the excellent educator Pierre Fourier; she had been trained in his methods by the external congregation at Troyes. But she adapted what she had acquired to the setting of New France. In a century when people in France were still wondering whether education was necessary for daughters of the lower orders, she insisted that schooling should be free: “To be able to give free instruction, the sisters content themselves with a minimum, do without everything and live sparsely everywhere.”

The competence of the teacher seems to be a requirement of our era. Yet Marguerite Bourgeoys called for it, with an astonishing perspicacity: “The sisters must take the trouble to acquire knowledge and skill for all kinds of tasks. The members of the Congrégation sacrifice their health, their satisfaction and their rest for the sake of the girls they teach.”

In an age when the birch-rod was still widely employed, Mother Bourgeoys recommended the use of chastisement only “very rarely, always with prudence and extreme moderation, it being remembered that one is in the presence of God.”

Thanks to this goodness, which was so to speak the hallmark of her pedagogy, Marguerite Bourgeoys managed to win over the little Indian girls and to form the first two nuns to come from the native races of America: an Algonkin, Marie-Thérèse Gannensagouas, and an Iroquois, Marie-Barbe Atontinon.

It is above all in the founding of her community, the Congrégation de Notre-Dame, that Marguerite Bourgeoys appears modern to us; through her wonderful adaptations and her magnificent achievements she stands in the forefront of our history. In New France, in the 17th century, she founded a community of non-cloistered sisters, an extraordinary innovation at that time, for the cloistered life was the only one known for women. She did not succeed without difficulties. On two occasions she had even to resist respectfully her bishop’s desire to link up the Congrégation with the Ursulines of Quebec, in order to avoid increasing the number of religious orders in a poor colony and exposing himself to the risks of a bold new venture.

Marguerite Bourgeoys hit upon a formula which was wonderfully suited to the new country. Her nuns, although they took vows, were “secular,” that is to say they “were not cloistered,” any more than Our Lady herself: “The Holy Virgin was not cloistered, but she everywhere preserved an internal solitude, and she never refused to be where charity or necessity required help.” For this reason the first nuns went on horseback, on foot, or by canoe, to teach the catechism in the dwellings scattered along the shores of the St. Lawrence. And “in order not to be a burden to anyone,” they had to see to their own subsistence.

The uniform costume given by Marguerite Bourgeoys to her nuns did not seem very well suited, one would say, to such a laborious life. But however complicated and cumbersome it might appear today, one must admit that at that period it was fairly well “in fashion,” similar to what women then wore: long dress, fichu, and headdress of “Rouen cloth.”

Marguerite Bourgeoys’s nuns were of a profoundly religious cast of mind; she imparted to her community a strong spiritual quality. Following the example of Mary, the sisters of the Congrégation were intended to be “wanderers and not cloistered.”

In this entirely original fashion Marguerite Bourgeoys built an edifice of which the survival is certainly the most convincing proof that its mysticism is based upon realism. She promised her nuns nothing but “bread and soup,” a prospect that scarcely invited entry into her community. Yet at her death in 1700 there were 40 sisters to continue her work. By 1961 the community numbered 6,644 nuns. In that year, in 262 establishments in Canada, the United States, and Japan, the Congrégation de Notre-Dame reached nearly 100,000 pupils through its teaching, a diffusion of the gospel which prolongs in time and space the presence of Marguerite Bourgeoys.

At the age of 78 Marguerite Bourgeoys wrote her memoirs. Disturbed by the way in which the early austerity was being relaxed, the clear-sighted founder put down in writing her warnings, her ideas on the spirit of the community, and some personal memories which explain the founding of the Congrégation de Notre-Dame. This point of view and this mood account for the style and tone of the memoirs and the choice of the memories. Several of Marguerite Bourgeoys’s manuscripts were lost in the fire that destroyed the mother house in 1768. Those that escaped destruction were copied at the time of the informative enquiry for the cause of beatification in 1867, and the copies were preserved in the archdiocesan archives at Montreal. The original, kept at the Congrégation de Notre-Dame, was almost entirely consumed in the fire of 1893. That same year some sisters went to the archdiocesan archives to copy the transcription of the documents written in 1867 for the cause of beatification. In the archives of the mother house, at Montreal, are to be found today, in addition to the 1893 copy, the microfilm of the first copy belonging to the archdiocesan archives, and of the copy sent to the Vatican in 1868, and the bound photostats of these two copies.

ACND, MS, M1, V1, V2, Écrits autographes de sœur Marguerite Bourgeois. [Marguerite Bourgeoys], Marguerite Bourgeois, éd. Hélène Bernier (Classiques canadiens, III, Montréal et Paris, 1958).

A great deal has been written on Marguerite Bourgeoys. Only the principal biographies are listed below, in chronological order: Charles Glandelet, Le vray esprit de Marguerite Bourgeoys et de l’Institut des sœurs seculières de la Congrégation de Notre-Dame établie à Ville-Marie en l’Isle de Montréal en Canada, 1701; unpublished MS, copies in ACND, particularly valuable because the author, Marguerite Bourgeoys’s spiritual director, wrote it only a few months after the death of the foundress and used the accounts and recollections of her contemporaries. [Étienne Montgolfier], La vie de la Vénérable Marguerite Bourgeoys dite du Saint-Sacrement (Ville-Marie [Montréal], 1818), known as the Vie de 1818, and the first biography printed in Canada. [É.-M. Faillon], Vie de la Sœur Bourgeoys, fondatrice de la Congrégation de Notre-Dame de Villemarie en Canada, suivie de l’histoire de cet institut jusqu’à ce jour (2v., Villemarie [Montréal], 1853). Sister Saint Ignatius Doyle, Marguerite Bourgeoys and her Congregation (Gardenvale, P.Q., 1940). Albert Jamet, Marguerite Bourgeoys, 1620–1700 (2v., Montréal, 1942). Yvon Charron, Mère Bourgeoys (1620–1700) ([Montréal], 1950). L.-P. Desrosiers, Les dialogues de Marthe et de Marie (Montréal et Paris, [1957]).

Revisions based on:

Bibliothèque et Arch. Nationales du Québec, Centre d’arch. de Montréal, CE601-S51, 13 janv. 1700. Congrégation de Notre-Dame, “Bringing out our inner light!”: cnd-m.org/en/home (consulted 25 March 2014).

Cite This Article

Hélène Bernier, “BOURGEOYS, MARGUERITE, dite du Saint-Sacrement,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 1, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed January 2, 2026, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/bourgeoys_marguerite_1E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/bourgeoys_marguerite_1E.html |

| Author of Article: | Hélène Bernier |

| Title of Article: | BOURGEOYS, MARGUERITE, dite du Saint-Sacrement |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 1 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1966 |

| Year of revision: | 2015 |

| Access Date: | January 2, 2026 |