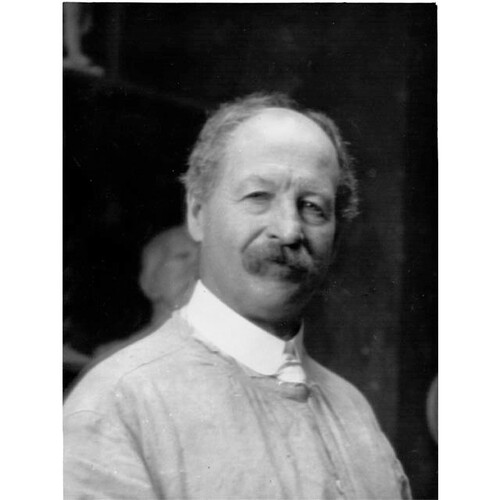

Source: Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

HILL, GEORGE WILLIAM, marble cutter, sculptor, and teacher; b. 8 May 1861 in Shipton (Danville), Lower Canada, son of George Taylor Hill and Eleanor A. Carty; m. 16 April 1895 Elsie Annette Kent in Granby, Que., and they had at least one son and two daughters; d. 17 July 1934 in Outremont (Montreal) and was buried there two days later in Mount Royal Cemetery.

After studying at St Francis College in Richmond, George William Hill worked for eight years as a marble cutter with his father. During most of that time he practised this trade as chief sculptor. In March 1887 he attended the modelling class of Olindo Gratton* at the school of the Council of Arts and Manufactures of the Province of Quebec in Montreal at the same time as the painter Maurice Galbraith Cullen. Admitted to the École Nationale des Beaux-Arts in Paris, Hill started his training there on 11 June 1889 with painters Jean-Paul Laurens and Léon Gérôme and with painter and sculptor Alexandre Falguière. That year he took courses from the sculptor Henri-Michel Chapu at the Académie Julian. Hill also trained with sculptor Jean-Antoine Injalbert at the Académie Colarossi. The Canadian artists George Agnew Reid*, William Brymner*, Joseph-Charles Franchère, Joseph Saint-Charles, William Edwin Atkinson, Albert Curtis Williamson, Charles Gill*, and Cullen studied in Paris during the same period.

After returning to Montreal in 1894, Hill set up his sculpture studio in Saint-David alley and worked with the architects William Sutherland and Edward Maxwell*. He produced sculpted interiors for them in private houses, such as that of Louis-Joseph Forget* on Rue Sherbrooke. In addition, he created models of ornaments and the pediment of the Saskatchewan Legislative Building in Regina (1911–12). This collaboration would last until World War I. Between 1898 and 1912 the sculptor Elzéar Soucy was one of his numerous assistants.

In 1897 Hill delivered his first monument, the Lion of Belfort, which was commissioned by the Sun Life Assurance Company of Canada to mark Queen Victoria’s diamond jubilee. The monument, whose pink granite pedestal was designed by the architect Robert Findlay and which holds a drinking fountain, is surmounted by a bronze reclining lion. This figure is a scaled-down version of the work by French sculptor Frédéric-Auguste Bartholdi that sits at the foot of the citadel of Belfort, France. In December 1902 Hill won his first competition: finishing ahead of Canadian and American colleagues, he secured the contract to produce the Strathcona and South African soldiers’ memorial [see Sir Donald Alexander Smith*], which required several trips between Montreal and Paris. In the latter city he opened a studio to complete the commission and had the casting done at the renowned Maison Barbedienne. The result was unveiled in 1907 in Dominion (Dorchester) Square in Montreal, where the Lion of Belfort had also been placed. The work, which remains the only equestrian monument in Montreal in the early 21st century, met with tremendous success and ensured the fame of its creator. In fact, it is probably his most accomplished creation, one in which the strong cohesion between the statue and its pedestal achieves a balance of forms. The masterful rendering of the rearing horse, the attention to anatomical detail, and the figure of the soldier that counterbalances the whole all contribute equally to the quality of the sculpture, while the representation of the figures in action creates a dramatic tension that injects dynamism into the monument.

In 1908 Hill established his studio at 255 Rue de Bleury, where Brymner also worked. The painter Edmond Dyonnet would set himself up there in 1916. While continuing to work for the Maxwells, Hill created, for the city of London, Ont., another monument to commemorate the soldiers who had died in the South African War. It was unveiled in 1912 while he was preparing the statue of George Brown* that would be erected on Parliament Hill in Ottawa the following year.

Also in 1912, Hill won the prestigious competition to erect a monument to Sir George-Étienne Cartier*, marking the centenary of his birth, at the foot of Montreal’s Mount Royal. To execute the sculptures that constituted the work, he set up a studio in Brussels near the Compagnie des Bronzes, where the elements were cast. World War I delayed the inauguration of the monument until September 1919, however; one of the figures remained stranded in Brussels. As they had done for the pedestal of the Strathcona and South African soldiers’ memorial, the Maxwell brothers designed the base and laid out the square where it was situated. The Sir George-Étienne Cartier monument, at a height of more than 100 feet and comprising 18 figures cast in bronze, was without equal in Quebec. Furthermore, since it was conceived as one of the city’s beautification projects, an appropriate location was selected for installing it to best advantage. These factors did not succeed in masking a problem inherent to the work, and one for which it has always been criticized: the representation of Cartier is literally overshadowed by a column that is too tall and which is surmounted by a huge figure of Fama, thereby upstaging him. Yet the cities of Quebec (1920), Saint-Antoine-de-Padoue (Saint-Antoine-sur-Richelieu) (1919), and Winnipeg (1922) appreciated the work enough to commission other, albeit more modest, monuments honouring Cartier. Responding to this enthusiasm, the sculptor lost no time in having 12 small-scale busts of the politician cast, two of which were given to Sir Robert Laird Borden and Sir Lomer Gouin* by the Cartier Centenary Committee.

At the end of World War I, Hill, like numerous colleagues, was awarded several contracts by towns and cities wishing to pay homage to citizens who had died on the battlefields. Between 1920 and 1930 he designed monuments for Toronto, Ottawa and Morrisburg, Ont.; Montreal West, Magog, Westmount, Lachute, Richmond and Sherbrooke, Que.; Charlottetown; and Pictou, N.S. His monument to Thomas D’Arcy McGee* was unveiled on Parliament Hill in Ottawa in 1922. In the same city in 1931 Hill inaugurated the statue in honour of Harold Fisher, which was commissioned by a group of citizens to mark the contribution of the former mayor (1917–20) to the founding of the Civic Hospital. Among the works by the artist, one that stands out is the Nursing sisters’ memorial (1926): mounted in the Hall of Honour of the centre block of the Parliament Buildings, it is a bas-relief in Carrara marble, which Hill produced in Italy and shipped to Ottawa. Over the course of his career he fashioned several busts, including those of the painters Brymner (his diploma piece for the Royal Canadian Academy of Arts, 1918) and Dyonnet (1932).

Hill had taught modelling at the Art Association of Montreal in 1896–97 and at the Renaissance Club shortly after it opened in 1899. His deafness probably hampered his pursuit of a teaching career. A member of the Pen and Pencil Club from 1907 and the Arts Club of Montreal from 1912 to 1925, Hill became an associate member of the RCA in 1908 and was elected an academician in 1917. In Paris he had exhibited at the 1905 Salon of the Société des Artistes Français (Fragment du monument élevé aux soldats canadiens, à Montréal). He took part in numerous exhibitions at the AAM and the RCA.

George William Hill, a man respected and valued by his peers, was one of the most famous sculptors in Canada in his day. His work is a fine example of the academic sculpture practised in France at the turn of the 20th century. The Strathcona and South African soldiers’ memorial, one of the very few equestrian examples in Canada, as well as the Sir George-Étienne Cartier monument, still the most imposing statue in Quebec at the beginning of the 21st century, remain without a doubt the sculptor’s most interesting creations. Their power ensures his posterity.

Some of the tools used by George William Hill, as well as some of his works, can be found in the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts. Sculptures by the artist are also held at the Musée National des Beaux-Arts du Québec in Quebec City, the Lachine Museum in Montreal, the Reford Gardens in Grand-Métis, the National Gallery of Canada in Ottawa, the Art Gallery of Hamilton, and the Agnes Etherington Art Centre at Queen’s University in Kingston.

A file on Hill, which includes orders he sent to the Compagnie des Bronzes, is held in the company’s fonds at the National Arch. of Belgium and the State Arch. in the Provinces in Brussels. Documents on Hill’s completed monuments are held at the Section des Arch., Ville de Montréal. Reports on competitions and unveilings of the sculptor’s public monuments can be found in numerous newspaper articles of that time.

BANQ-E, CE501-S47, 17 sept. 1864; CE502-S80, 16 avril 1895. FD, United Church, Côte-des-Neiges (Montreal), 17 July 1934. Le Devoir, 18 juill. 1934. La Presse, 21 mai 1920. Saturday Night, 14 May 1938. The architecture of Edward & W. S. Maxwell (exhibition catalogue, Montreal Museum of Fine Arts, 1991). E.‑J. Auclair, “Les fêtes du monument Cartier à Montréal,” Rev. canadienne (Montréal), nouv. sér., 24 (juillet–décembre 1919): 241–63. Can., Dept. of Canadian Heritage, Canadian heritage information network, “Artists in Canada”: app.pch.gc.ca/application/aac-aic/description-about.app?lang=en (consulted 14 Dec. 2017). Edward & W. S. Maxwell: a guide to the archive, ed. Irena Murray (Montreal, 1986). La Fonderie, La Compagnie des bronzes de Bruxelles: fabrique d’art ([Bruxelles, 2003]). Aline Gubbay, “Three Montreal monuments: an expression of nationalism” (ma thesis, Concordia Univ., Montreal, 1978). W. H. Ingram, “Canadian artists abroad,” Canadian Magazine, 28 (November 1906–April 1907): 218–22. Laurier Lacroix, “Berlin-Paris: George W. Hill et Lyonel Feininger correspondants de Frederick S. Coburn,” Journal of Eastern Townships Studies (Lennoxville [Sherbrooke], Que.), no.14 (spring 1999): 79–91. Alfred Laliberté, Les artistes de mon temps, Odette Legendre, édit. (Montréal, 1986). R. J. Lamb, “Canadian sculpture in the age of Laurier,” in The arts in Canada during the age of Laurier, ed. R. J. Lamb ([Edmonton, 1988?]), 1–10. Olivier Maurault, “Les monuments de Montréal,” Rev. trimestrielle canadienne (Montréal), 24 (1937): 119–36; “Une famille de sculpteurs: les Soucy,” RSC, Trans., 3rd ser., 36 (1942), sect.: 71–76. M. J. Mount, “George Hill, A.R.C.A.,” Canadian Century and Canadian Life & Resources (Montreal), 2 (1910), no.23: 7. P.‑G. Roy, Les monuments commémoratifs de la province de Québec (2v., Québec, 1923), 1. Royal Canadian Academy of Arts: exhibitions and members, 1880–1979, comp. E. de R. McMann (Toronto, 1981). Robert Shipley, To mark our place: a history of Canadian war memorials (Toronto, 1987).

Cite This Article

Joanne Chagnon, “HILL, GEORGE WILLIAM,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 16, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed April 26, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/hill_george_william_16E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/hill_george_william_16E.html |

| Author of Article: | Joanne Chagnon |

| Title of Article: | HILL, GEORGE WILLIAM |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 16 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of revision: | 2020 |

| Access Date: | April 26, 2025 |