Source: Link

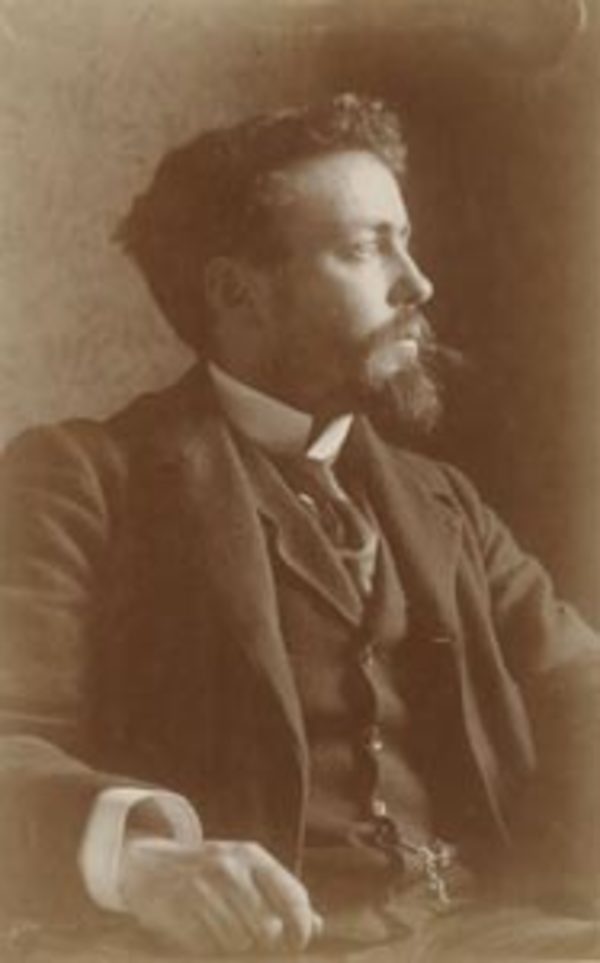

CULLEN, MAURICE GALBRAITH (he often signed Maurice Cullen), painter; b. 6 June 1866 in St John’s, son of James Francis Cullen, a clerk, and Sarah Ward; m. 3 Nov. 1910 Barbara Merchant, widow of Edward Watson Pilot, in Newfoundland; they had no children; d. 28 March 1934 in Chambly-Canton (Chambly), Que., and was buried the following day in Mount Royal Cemetery in Outremont (Montreal).

Artistic education

Little information survives about Maurice Galbraith Cullen’s early years. It is thought that his parents left St John’s for Montreal sometime after he was born. At about age 15, Cullen was engaged as a clerk with Gault Brothers and Company, a wholesale importer and manufacturer of woollens. While working there, between December 1885 and February 1887, he took classes in drawing, anatomy, and modelling given by Louis-Philippe Hébert* at the school of the Council of Arts and Manufactures of the Province of Quebec. Following Hébert’s departure on 21 February, two of his students, Olindo Gratton* and Philippe Laperle, took over teaching; Cullen probably attended their classes until March. That year was marked by the death of his mother on 17 August.

Cullen arrived in Paris in November 1888 with the firm intent of obtaining formal and recognized artistic training. He registered at what was known as the Canadian commission general on the 17th – at the same time as his uncle Michael O’Brien Ward, with whom he had travelled, and Maurice O’Reilly, future arts columnist for the Paris-Canada newspaper. That day Hector Fabre*, the official representative of the Quebec and Canadian governments in Paris (as well as the founder of Paris-Canada), signed a letter addressed to the director of the École Nationale des Beaux-Arts to facilitate Cullen’s admission. Cullen became an aspirant; that is, he was authorized to study in galleries of ancient art, attend theory classes, and take advantage of the library. It remained for him to pass the concours des places, a series of tests held twice a year in February and June that granted admission to the École Nationale des Beaux-Arts. He prepared by first enrolling at the Académie Colarossi, where he sought the support of his drawing teacher, Edmond-Louis Dupain, to obtain the right to sit the examination in June 1889. In his letter of 17 June, Dupain described Cullen thus: “A student … whom I believe to be quite capable of taking this test.” It is not known, however, whether the request was granted or whether in fact Cullen took the exam. The frequency of his attendance thereafter at the École Nationale des Beaux-Arts is difficult to establish.

Cullen spent a short time at the Académie Julian, from 20 Jan. to 3 Feb. 1890. His name appears in the register of the studio of Jules-Joseph Lefebvre and Benjamin-Constant, on the same date and beside that of painter James Wilson Morrice*, who had just arrived in France. The well-informed O’Reilly stated in the Paris-Canada issue of 20 Dec. 1890 that “M. Cullen has spent a good part of this year in Venice and Milan, and intends to visit the principal artistic centres of Europe again next year.” He then mentioned Cullen’s return to the École Nationale des Beaux-Arts, in the studio of painter Élie Delaunay. Cullen was enrolled on 3 Nov. 1890, even though he had not passed the February and June entrance tests. Such a situation was not unusual since failing the exam, which happened more frequently than passing it, did not mean immediate exclusion from the school. His training, if it continued, finished at the latest when classes ended in July 1891. Delaunay died suddenly on 5 Sept. 1891, and Cullen’s name no longer appeared on the registers of the École Nationale des Beaux-Arts, which demonstrates that he had abandoned the idea of being admitted.

From 1891 there is every indication that Cullen remained on the margins of official institutions. The painter resided only sporadically in Paris. He registered twice at the Canadian commission general, on 31 Oct. 1891 and 19 Nov. 1892, and gave a new address each time. He was already developing his own creative method, one rooted in experience, as shown in Seascape, which he painted outdoors very quickly in a single working session in 1890. O’Reilly, on seeing Cullen’s recent paintings, wrote in his Paris-Canada column: “Mr. Cullen rather inclines towards the Impressionist school and that is certainly not a reproach on our part, for this tendency proves the artist’s loathing of banality, which we cannot do enough to encourage.” One month later, on 20 Jan. 1891, Paris-Canada repeated the columnist’s words in full, and would long associate Cullen’s name with the Impressionist school.

Sojourns in Biskra, El-Kantara, and Moret-sur-Loing

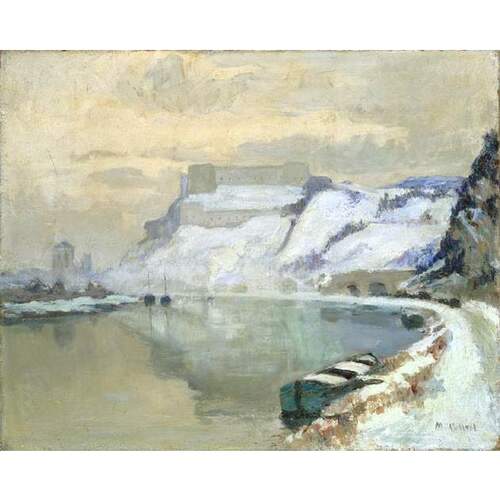

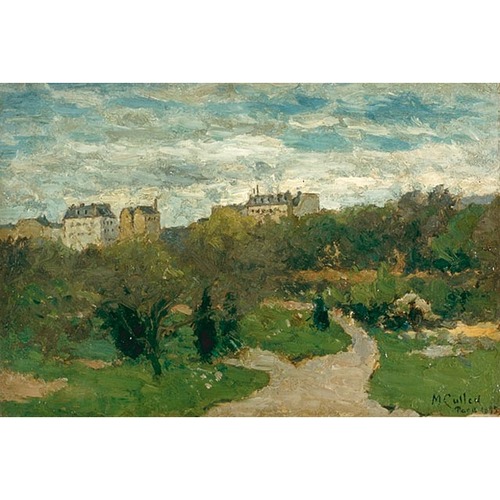

In 1893 Cullen travelled to Biskra and El-Kantara in Algeria, before settling in Moret-sur-Loing in the l’Île-de-France region the following year. When he arrived at Biskra, it was a major tourist site on the edge of the Sahara desert. It was also appealing to many artists who belonged to the Society of French Orientalist Painters. Their first exhibition was held in Paris in 1893. Faced with the challenge of the blinding light, Cullen drew clear, straightforward images without staging or theatricality (Biskra, 1893). Between 1894 and 1895 he devoted all his attention to the scenery along the banks of the Loing River, lingering for a long time in Moret-sur-Loing. Except for the fact that Alfred Sisley was there (nothing suggests that the two painters were ever in touch), the decision to settle in the community was rare and unusual. Artists preferred Grez-sur-Loing, which Cullen had known about since at least 1892 through the painter William Blair Bruce* and his wife, the sculptor Carolina Benedicks; they had been established there since 1889. There is no account of that stay of several months, yet it sheds light on the Impressionist style Cullen developed as he attempted to reconcile the muted tones of the Naturalist movement with the sensation of the moment. He conveyed this approach in paintings such as Moret, Winter (1895) by compressing the planes and using his brush much like a pen.

Société Nationale des Beaux-Arts

Throughout his stay in Moret-sur-Loing, Cullen retained an address in Paris, where he was associated with the painter Alfred Roll. He referred to him as one of his teachers, as he had Delaunay. Roll had never taught at the École Nationale des Beaux-Arts or at the Julian and Colarossi academies. He shared, with Pierre Puvis de Chavannes, the studio of painter Léon Bonnat, located at 85 Rue Ampère, Paris, until it closed in 1894. Significantly, Roll and Puvis de Chavannes were very active in the Société Nationale des Beaux-Arts, of which they had been founding members in 1890. Roll encouraged his pupils to present their work at its annual salon, and, in fact, Cullen was the first Canadian to exhibit there in 1894. The society being an elitist one, artists were granted admission through member invitation. Therefore, only after demonstrating sufficient quality and promise in his painting was he elected as an associate at the meeting of 20 May 1895, chaired by Puvis de Chavannes.

Return to Quebec and exploration of winter themes

Building on this recognition, Cullen went to Montreal in the summer of 1895, but he did not settle there, having neither a permanent address nor a studio. His principal objective was to exhibit. With the results of his stay in Algeria – Une rue d’El Kantara and An African river (c. 1893–95) – he made his debut on the artistic scene in October by displaying his work at the Notre-Dame Hospital charity bazaar, and in December he rented vacant premises to mount a more ambitious exhibition. He left again for Paris in March 1896 and enrolled as a copyist at the Louvre in April. Cullen’s real return to Quebec came in the middle of 1896, when he settled for several months in the Sainte-Anne-de-Beaupré area. At the beginning of December he exhibited the fruits of his labour at 258 Rue Saint-Jacques in Montreal. His choice of the new living environment was not surprising as its geography was similar to that of the Île-de-France region, where the northern climate had provided him with aesthetic stimulation not previously known. It combined in a single location what he had experienced separately in Biskra and Moret-sur-Loing: the palpable sensuality of France contrasting with the intense light of the Algerian sun.

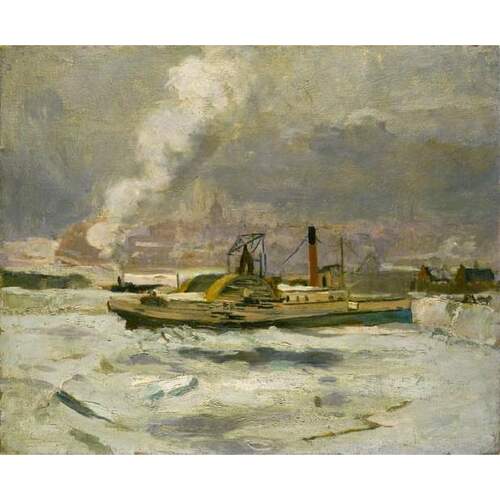

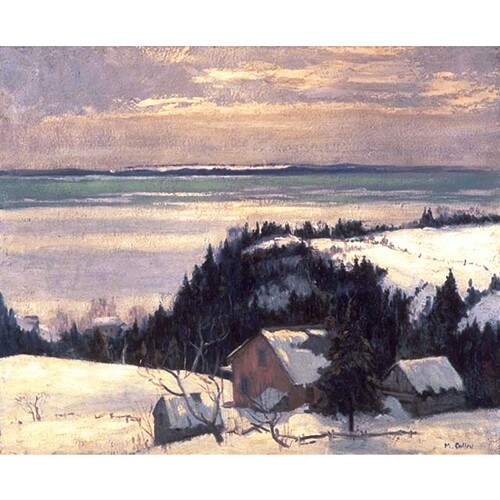

From 1896, Cullen’s devotion to the exploration of winter in his artistic endeavours, right from autumn’s end until the start of spring, was already evident (Logging in winter, Beaupré, 1896). His first sojourn in the Côte-de-Beaupré was a turning point: he was able to persuade Morrice, who had arrived in Montreal in November 1896, to spend January to March 1897 with him there to share the challenging experience. Historians would deem this moment the beginning of a modern art movement in Quebec. Its true significance, however, lies elsewhere – in the establishment of a daily rhythm that alternated between work and artistic sociability, and which became entrenched there between 1896 and 1900. The painter and teacher William Brymner*, who had introduced Cullen to the members of Montreal’s Pen and Pencil Club in 1895, joined him in Sainte-Anne-de-Beaupré the following year, along with artists Edmond Dyonnet and Edmund Montague Morris*. From 1896 to 1899 this small community of painters met annually in this locale, from mid-summer to the beginning of autumn. Each developed his own aesthetic individuality while working in harmony. The differences and parallels intrigued the critic of the Montreal Daily Star. In an article on 30 Dec. 1898, he advised readers to compare the work of Cullen and Brymner because “some of the pictures of the two artists were painted from the same vantage point, and at the same time.” Meanwhile, Cullen had set himself up in Montreal in 1898, opening a studio at 96 Rue Saint-François-Xavier.

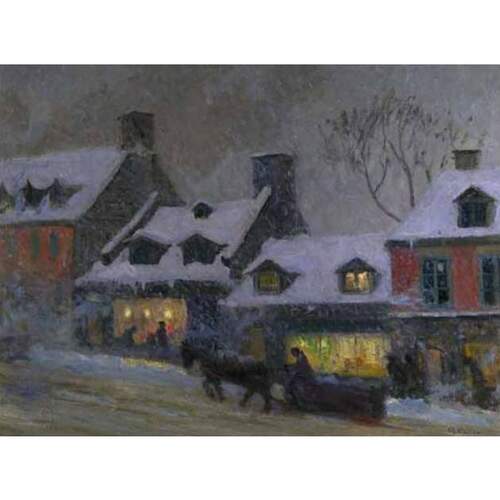

Travels in Europe

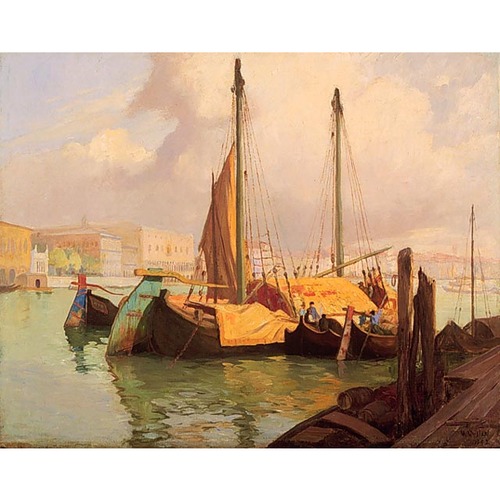

After a four-year absence, Cullen returned to France and registered at the Canadian commission general on 1 April 1900. During his two-and-a-half-year stay – he would return to Montreal in the autumn of 1902 – he travelled about a great deal, stopping for varying lengths of time in Venice, at Le Pouldu and Pont-Aven in Brittany, and in Dordrecht in the Netherlands. He was rarely alone, joining Brymner and Morrice in Venice during the summers of 1901 and 1902. These travels, organized around work, allowed him to vary his experiences in areas mainly frequented by tourists, where his view was never entirely that of a detached observer. His in situ sketches were full of picturesque references, such as the church of Santa Maria della Salute in Venice and the Great Church in Dordrecht, subjects found in the works he exhibited in Montreal from 1903 onwards. He took a similar approach the next year in the paintings that resulted from his decision to represent Quebec City as a metaphor for winter. He oriented the view of the city from Lévis (Winter evening, Quebec, c. 1905) or with the Château Frontenac depicted in the foreground of the panorama. Painting in his studio from outdoor studies, he gave both Quebec and Lévis – viewed from a height and from a distance (L’Anse-des-Mères, 1904; Cape Diamond, 1909) – an aura of grandeur, imparting an evocative power to the light and the darkness that had not been seen before (Twilight, Dufferin Terrace, 1905). Between 1903 and 1913 his pictorial talent developed, revealing that he was more interested in atmosphere and sensation just at the moment when shapes lose their solidity than he was in a fleeting impression. In 1912 in Montreal, Cullen injected a new rhythm into his paintings by depicting in an urban setting a team of horses in the middle of a snowstorm, locking the viewer’s gaze into an enclosed space where sounds are muffled and vision blurred (The Blizzard, Craig Street, Montreal, 1912). It was during this period that Cullen was recognized by his peers. He had been an associate member of the Royal Canadian Academy of Arts since 1899, but he took a number of years to produce his 1907 diploma piece, Summer night, and therefore was not officially admitted until that April. He was twice awarded the Jessie Dow prize, in 1911 and 1913.

Relationships with other artists

In 1905 Brymner and Cullen built a studio in Saint-Eustache, demonstrating that friendship and aesthetic affinities are inseparable from shared achievements, all the while maintaining their individual identities. In 1908 they participated in decorating the interior of Charles E. L. Porteous’s new summer home on Île d’Orléans. For the entrance hall, Cullen created a long frieze with a historical theme. That year he joined the brothers William Sutherland and Edward Maxwell*, both architects, in projects to decorate the interior of the Westmount house of Richard Ramsay Mitchell. This collaboration continued at the residence of James Thomas Davis in Montreal in 1911 and that of Louis Henry Timmins in Westmount in 1913. For each undertaking, Cullen tried something new, especially in the Timmins home, where he demonstrated perfect mastery of tonalism, embellishing the alcove of the billiard room with peaceful landscapes. On 16 May 1912 the Arts Club of Montreal was founded in Cullen’s studio (located at 3 Beaver Hall Square since about 1905). An offshoot of the Pen and Pencil Club, it arose from a desire to create a suitable meeting place for discussion and encouragement of the arts. Twenty-eight people were present on that occasion, including Brymner, painter John Goodwin Lyman*, and collector Frederick Cleveland Morgan; women were admitted only to the exhibitions. William Sutherland Maxwell and Cullen, close friends, held the posts of president and vice-president respectively.

In the spring of 1911, probably owing to new family obligations (his wife had five children from her previous marriage), Cullen became the resident teacher at the summer school of the Art Association of Montreal. Until 1923 lessons were given outdoors from the end of May to mid June – first in the Côte-de-Beaupré and then, from 1913, in the Eastern Townships.

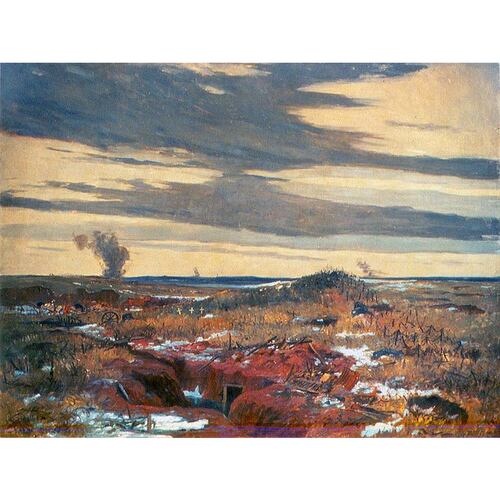

With the title of honorary captain, Cullen went to London in April 1918 under the auspices of the Canadian War Memorials Fund, initiated by Lord Beaverbrook [Aitken*]. On the front in France from June to September, he drew his subjects in situ and later in his London studio painted canvases from sketches, recording places and battles. The battlefields had a particularly painful resonance for Cullen, as can be seen in his Dead horse and rider in a trench (1918). His stepson John Pilot had been killed a few months earlier (29 June 1917) at Acheville, France, and three other stepsons also took part in the war: Edward F., William, and Robert Wakeham. From January to March 1919, Cullen was in Belgium, at Huy and Namur, and he then returned to Quebec to resume his summer courses from 2 to 16 June in Sweetsburg (Cowansville).

Exhibitions

Cullen took little interest in international exhibitions of his work, such as those in St Louis, Mo., in 1904, London in 1910, and Paris in 1927. He had maintained his public presence primarily with regular exhibitions in Montreal, but also in Toronto and, more sporadically, in Ottawa, Hamilton, and Halifax. He put forward only a small number of paintings each time, however, to avoid risking disfavour by placing too many comparisons under the eyes of critics. It was therefore a major turning point when in January 1923 the painter’s first solo exhibition was held in William Robinson Watson’s Montreal gallery. A dozen others followed and the last, in April 1935, was devoted to the sketches that Cullen kept in his studio, reviving the memory of the painter who had died the year before, following a two-year illness that forced him to curtail his activities. Each exhibition comprised over 30 works linked by the painter’s signature images of the Canadian winter. The commercial imperatives and ties of friendship that bound Cullen and Watson led the artist to use a repetitive approach in his landscapes. He restricted his palette to the simple, reiterated elements of the Laurentians around Lac Caché, the Rivière du Nord, and Lac Tremblant, where he had built himself a studio in 1920. This period was also one of experimentation with pastels, during which the artist strove to maintain separate tonalities on large-format paper without mixing his chalks (Chute de neige sur la Rivière du Nord, c. 1929). Watson, who observed these efforts, characterized the process as “legerdemain.”

Assessment

Robert Wakeham Pilot was already well established as a painter when his stepfather died. He was indebted to Cullen for the pictorial qualities in his work, but he added a narrative dimension to his subjects that was largely absent from Cullen’s paintings, as illustrated in Twilight, Lévis (1933), Pilot’s diploma piece for the Royal Canadian Academy of Arts in 1935. Paying tribute to Maurice Galbraith Cullen in April 1934, Watson summed up the man and the artist in two words: simplicity and sincerity. He could have added that he was steadfast and consistent, for Cullen remained faithful to the fundamental principles established during his years of training in France: to go beyond what can be seen in order to capture sensation in stable, ordered compositions. Over a little more than 35 years, Cullen produced an oeuvre that demonstrated true unity while concealing the searching spirit that informs all his work. He made perception outside the studio his life’s work, taking very little interest in the human figure or making a statement through his painting. In this way, beneath the seeming monotony of immediately comprehensible subjects, he leads the viewer to reflect on the tension between the actual world and its representation. Having discovered its possibilities in 1890, he made pictorial matter, colour, and light his real artistic project.

The first painting by Maurice Galbraith Cullen to enter a public collection was L’été, acquired by the French government in 1895. In Canada the majority of museums with art collections hold important works by Cullen: the Musée National des Beaux-Arts du Québec (Québec), Montreal Museum of Fine Arts, National Gallery of Can. (Ottawa), Canadian War Museum (Ottawa), Art Gallery of Ont. (Toronto), Art Gallery of Hamilton and Art Gallery of Windsor in Ontario, and Winnipeg Art Gallery. The presence and sales of his work in the Canadian art market indicate a more complex artistic personality than that presented by the collections in institutions.

The exhibition catalogue Maurice Cullen, 1866–1934, prepared by Sylvia Antoniou in 1982 for the Agnes Etherington Art Centre of Queen’s Univ. in Kingston, Ont., remains a reference for knowledge about Cullen; since its appearance, there has been no other significant study. The catalogue provides detailed information about his exhibitions (places, dates, displayed works) and includes a chronological list of his awards. Annually between 1893 and 1934 he gave simultaneous exhibitions of his works in several venues. A large body of critical writings that accompanied these presentations provides insight into the works exhibited.

The author consulted more than 30 contemporary newspapers. Most articles can be found in the Montreal Gazette (1896–1934), Montreal Daily Herald (1899–1914), Montreal Daily Star (1897–1934), Montreal Daily Witness (1897–1913), Montreal Herald (1919–25), and Montreal Herald and Daily Telegraph (1914–19).

Arch. Nationales (Paris, Fontainebleau et Pierrefitte-sur-Seine), AJ52 (fonds de l’École nationale supérieure des beaux-arts), dossier 277. BANQ-CAM, CE601-S51, 8, 11 janv. 1868. Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, “Newfoundland church records, 1793–1945”: www.familysearch.org (consulted 26 June 2016). FD, Unitarian Messiah (Montreal), 29 March 1934. LAC, R233-35-2, Que., dist. Montreal (90), subdist. St Louis Ward (E): 109; RG 150, Acc. 1992-93/166, box 2199-37. Le Devoir, 28 mars 1934. Evening News (Montreal), 29 July 1914. Gazette, 24 Jan., 2 Dec. 1896; 3 April 1909; 7 June 1913; 5 April 1918; 27 May 1919; 28 March 1934; 19 May 1962. Montreal Daily Star, 30 Dec. 1898; 9 April 1909; 1 April, 17 May 1911; 28 March 1934; 12 May 1962. Paris-Canada (Paris), 22 nov. 1888; 20 déc. 1890; 20 Jan., 31 oct. 1891; 19 nov. 1892; 9 juin 1894; 1er, 15 avril 1900. La Presse, 16 oct. 1895, 28 mars 1934. Sylvain Allaire, “Élèves canadiens dans les archives de l’École des beaux-arts et de l’École des arts décoratifs de Paris,” Journal of Canadian Art Hist. (Montreal), 6 (1982): 98–111. Artists, architects and artisans: Canadian art 1890–1918, ed. C. C. Hill (exhibition catalogue, National Gallery of Can., 2013). Jean Chauvin, Ateliers: études sur vingt-deux peintres et sculpteurs canadiens, illustrées de reproductions d’œuvres (Montréal et New York, 1928). Béatrice Crespon-Halotier, Les peintres britanniques dans les salons parisiens des origines à 1939: répertoire (Dijon, France, [2003]). Directory, Montreal, 1865–1930. Romain Gour, “Maurice Cullen: un maître de l’art au Canada (1866–1934),” Qui? (Montréal), 3 (1949–51): 41–64. Hugues de Jouvancourt, Maurice Cullen (Montréal, 1978). Laurier Lacroix, “Les artistes canadiens copistes au Louvre (1838–1908),” Journal of Canadian Art Hist., 2 (1975): 54–70. R. J. Lamb, The Canadian Art Club, 1907–1915 (exhibition catalogue, Edmonton Art Gallery, 1988). David McTavish, Canadian artists in Venice (exhibition catalogue, Agnes Etherington Art Centre, 1979). Maurice Cullen, 1866–1934 (exhibition catalogue, Art Gallery of Hamilton, 1956). Maurice Cullen and his circle (exhibition catalogue, National Gallery of Can., 2009). Bernard Mulaire, “Olindo Gratton et Louis-Philippe Hébert: une relation professionnelle entre deux sculpteurs à la fin du XIXe siècle,” Journal of Canadian Art Hist., 12 (1989): 22–49. A. K. Prakash, Impressionism in Canada: a journey of rediscovery (Stuttgart, Germany, 2015). Dennis Reid, “Impressionism in Canada,” in World impressionism: the international movement, 1860–1920, ed. Norma Broude (New York, 1990). Visions of light and air: Canadian impressionism, 1885–1920, ed. Robert Stacey and Elizabeth Ferrer (exhibition catalogue, Americas Soc. Art Gallery, New York, 1995). W. R. Watson, “Maurice Cullen, , 1866–1934,” Royal Architectural Instit. of Can., Journal (Toronto), 11 (1934): 64; Maurice Cullen, .: a record of struggle and achievement (Toronto, 1931). William Brymner: artist, teacher, colleague, ed. Alicia Boutilier and Paul Maréchal (exhibition catalogue, Agnes Etherington Art Centre, 2010).

Cite This Article

Didier Prioul, “CULLEN, MAURICE GALBRAITH (Maurice Cullen),” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 16, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed December 30, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/cullen_maurice_galbraith_16E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/cullen_maurice_galbraith_16E.html |

| Author of Article: | Didier Prioul |

| Title of Article: | CULLEN, MAURICE GALBRAITH (Maurice Cullen) |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 16 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 2022 |

| Year of revision: | 2022 |

| Access Date: | December 30, 2025 |