Source: Link

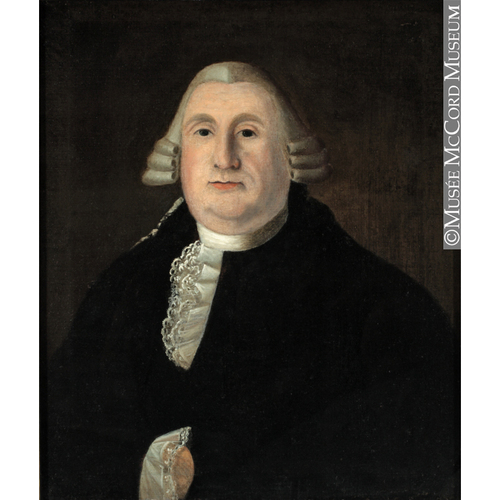

HERTEL DE ROUVILLE, RENÉ-OVIDE, lieutenant general for civil and criminal affairs, director of the Saint-Maurice ironworks, chief road commissioner (grand voyer), and judge of the Court of Common Pleas; b. 6 Sept. 1720 at Port-Toulouse (near St Peters, N.S.), son of Jean-Baptiste Hertel* de Rouville and Marie-Anne Baudouin; d. 12 Aug. 1792 in Montreal (Que.).

Unlike his father, his brother Jean-Baptiste-François, his numerous uncles, and his paternal grandfather Joseph-François Hertel* de La Fresnière, René-Ovide Hertel de Rouville did not win renown through the noble feats of arms that glorified the Hertel name. Quite early in life he turned to the study of law, taking the courses given at Quebec by the attorney general, Louis-Guillaume Verrier*, who listed him as one of his new pupils in October 1743. Two years earlier Hertel de Rouville’s marriage had been the talk of the town. Against the wishes of his mother and guardian – his father had died in 1722 – he had married Louise-Catherine André* de Leigne, a woman 11 years his senior, in Quebec on 20 May 1741. His mother took the matter to court and won. On 12 June the Conseil Supérieur annulled the marriage and forbad the two parties concerned to live as man and wife. But their plight was brief, since on 22 October they again entered into wedlock, this time, it seems, with the consent of the two families. The couple were to have three daughters and two sons. Jean-Baptiste-Melchior*, the best known of their children, became a member of the first assembly in 1792 and later a member of the Legislative Council.

On 1 April 1745, at the age of 24, Hertel de Rouville was named to the office of lieutenant general for civil and criminal affairs in the royal jurisdiction of Trois-Rivières, probably through the influence of his father-in-law, Pierre André* de Leigne, who had been lieutenant general for civil and criminal affairs of the provost court of Quebec; this appointment was confirmed on 17 Oct. 1746. While performing these duties he was given a number of other responsibilities, the most important being that of director of the Saint-Maurice ironworks.

When François-Étienne Cugnet* had gone into bankruptcy in 1741 the Saint-Maurice ironworks reverted to the Domaine d’Occident and were placed under the intendant’s direct control. Numerous problems, including not insignificant difficulties related to the hiring of qualified workmen and to the workers’ productivity, had arisen. Loose behaviour and insubordination often created disorder and dissension. In 1747, therefore, Intendant Hocquart decided to delegate his lieutenant general of Trois-Rivières to investigate any dispute arising among the workers. In 1749 the new intendant, Bigot, renewed Hertel de Rouville’s commission, and in October of that year extended his responsibilities: the subdelegate was to conduct an inspection in order to “correct abuses . . . cut down expenses . . . and do everything that could contribute to the good and the advantage of this establishment.” Having thus become familiar with the operation, Hertel de Rouville was named to succeed Jean-Urbain Martel* de Belleville as director of the ironworks, probably in 1750. He would retain this post until the end of the French régime. Despite the critical remarks made by engineer Louis Franquet* during his inspection of the ironworks in 1752, it is difficult to judge Hertel de Rouville’s management of this enterprise, which was to be brought to a virtual standstill by the war of the conquest.

At the time of the conquest Hertel de Rouville went to France, anxious to find a position there. According to Abbé François Daniel he is supposed to have become steward of the Prince de Condé’s household. But when peace returned in 1763, he decided to rejoin his family in Trois-Rivières. He soon succeeded in entering into the good graces of Governor Murray, who on 20 Nov. 1765 appointed him chief road commissioner for the District of Montreal. On 5 Feb. 1767, a year after the death of his first wife, Hertel de Rouville married Charlotte-Gabrielle Jarret de Verchères, widow of Pierre-Marie-Joseph Raimbault de Saint-Blaint, in Montreal.

Hertel de Rouville retained the post of chief road commissioner until 1775, when Governor Guy Carleton* granted him a commission as conservator of the peace and commissioner for the District of Montreal. A similar commission, for the District of Quebec, was issued at the same time to notary Jean-Claude Panet. These appointments of the first two French Canadian judges under the British régime took effect on the very day the Quebec Act came into force, 1 May 1775. Although Carleton counted on winning over the conquered Canadians in this way, he would have been more successful had he fixed his choice on anyone but Hertel de Rouville, whose appointment produced more displeasure than satisfaction among the Canadians. As soon as he received word of the appointment, even before its official confirmation, the seigneur of Beauport, Antoine Juchereau* Duchesnay, hastened to express the most profound indignation. Writing to François Baby*, a prominent Quebec merchant and later a member of the Legislative Council, he commented: “How could the government possibly have cast its eye upon the greatest scoundrel and the biggest rogue on earth, and have him dispense what he has never known? . . . whether the government is badly informed or whether it wishes us ill . . . the name of the judge [Hertel de Rouville] makes me shudder for all remaining arrangements.” Baby, who shared this opinion and consequently considered the “promotion” dangerous for the public good, was equally pessimistic about the results to be expected from the Quebec Act: “I am very much afraid that the time is not far off when Canadians will be unable to console themselves for having asked for the new form of government.”

These fears and apprehensions were not unfounded, given the way in which Hertel de Rouville acted in carrying out his new duties. After seeing him in action, and suffering the repercussions of a judicial system which left a good deal of room for arbitrary decisions, Pierre Du Calvet, a fellow Montrealer, commented: “M. de Rouville is . . . [a man] of such an overbearing nature, of such an arrogant character, of a temperament so nearly despotic that it betrays itself everywhere . . . . A man completely puffed up with the pretensions of vanity . . . , unyielding in his opinions . . . , intolerant . . . , very much a formalist, biased . . . , warm enough towards his friends, whom I should more aptly call his clients and his protégés, but all fire and flame against his enemies.” This portrait quite accurately conveyed the salient traits of his personality, which, being well known to the public, earned him an unenviable reputation.

According to documents emanating from English speaking circles in the colony, the choice of Hertel de Rouville met with such general disapproval from his fellow citizens in Montreal that, had it not been for the events disturbing the province on the eve of the American invasion, they would have petitioned against his appointment. The British minority especially condemned the means Hertel de Rouville used to bring himself to the attention of the colonial authorities. It was common knowledge that the new judge had not hesitated to act as a “toady” as a way of courting the administration: “M. de Rouville is remarkable for taking every opportunity (as he speaks a little English) to throw himself in the way of the English inhabitants of Montreal in order to pick up what tales he can, to send them up to the Governour.” Indeed, less than a month before his appointment he had told Governor Carleton of his altercation with Thomas Walker in the market-place in Montreal. When Walker, expressing sympathy with the revolutionary cause, had declared publicly “that the peoples of the [American] colonies were honest folk who did not want to be slaves and who would defend their liberty and their rights as long as they had blood,” Rouville had publicly retorted: “The people who are listening to you, myself included, have never been slaves, any more than you have; and our submission to the king and his government guarantees us that we will always be free.”

By his own admission, through “his conduct and his zeal” as a loyal subject of his majesty Hertel de Rouville “drew the wrath of the rebels, who made him feel it as soon as they were in possession of the town of Montreal.” In fact he was speedily subjected to the severity of the impetuous Brigadier-General David Wooster, who after Richard Montgomery’s death had assumed command of the American occupation. In January 1776, having decided to proceed by force with the expulsion of the most prominent loyalists in the town, Wooster “ordered M. Hertel de Rouville to get ready to leave for the colonies.” Although the citizens of Montreal protested, the unfortunate magistrate got off with taking the road to Lake Champlain and being “kept a prisoner for 18 months.”

Upon his return to the province Hertel de Rouville was reinstated in judicial office as judge of the Court of Common Pleas for the District of Montreal; an ordinance of 25 Feb. 1777 had set up such a court of justice in each of the two main districts of the province. During the greater part of the last 15 years of his life this faithful collaborator with the new régime sat on this court along with his colleagues, Edward Southouse and John Fraser. Hertel de Rouville found he was better able to adopt his preferred methods of working with Fraser, who already had long experience as a judge and who in addition belonged to the French party within the Legislative Council.

The system set up by the Quebec Act for administering justice mirrored the authoritarian régime established by the British parliament at a crucial moment in the relations between the mother country and her North American colonies. Since this régime did not provide for the separation of powers or control over them, and hence favoured their concentration in the hands of the governor and of a small oligarchy in the Legislative Council, the persons enjoying the patronage dispensed by those in power could expect almost unlimited immunity. Justice Hertel de Rouville was thus able to perform his duties as a magistrate with impunity, despite all the complaints and criticisms he brought upon himself through his obviously unfair judgements, his arbitrary decisions, and the incongruity of his sitting drunk on the Bench, as he frequently did in the afternoon sessions. An irascible man, prone to violent fits of anger, he could easily make improper use of annoying procedures in order to impose his will.

Judges were so strongly protected by the established system that the initiative taken by Chief Justice William Smith, whose influence was predominant on Carleton (Dorchester), to conduct a “full investigation” into the administration of justice resulted in no change. This investigation, held during the summer and early autumn of 1787 and primarily aimed at the “conduct and partiality” of the Common Pleas judges, brought such a defensive reaction on their part that Smith was unable to obtain any positive results. Not only were the three principally involved – Adam Mabane, John Fraser, and Hertel de Rouville – not censured in any way by London, but their chief adversary, Attorney General James Monk*, was ordered to resign in the spring of 1789.

The chief justice’s setback was to render quite futile the bold attack made upon Justice Hertel de Rouville’s vexatious proceedings by Louis-Charles Foucher, a young lawyer who later became solicitor general of Lower Canada. In a petition to Lord Dorchester dated 4 Oct. 1790, Foucher demanded that justice be done him against his “oppressor,” who he said had “persecuted, stigmatized, and demeaned” him, and caused him “irreparable damage and harm” through “deliberate and constant opposition to the practice and exercise of his profession as a lawyer” and through the threat of depriving him of his right to plead, which “would have . . . completely destroyed his clients’ confidence [and] would have forced him to withdraw ignominiously from the bar.” As there was ample matter for an investigation, the decision was taken to set up a committee of the Legislative Council to hear witnesses.

The committee’s make-up left no room for doubt about the outcome of this unequal contest. Its chairman, François-Marie Picoté de Belestre, seigneurs Joseph-Dominique-Emmanuel Le Moyne* de Longueuil and René-Amable Boucher* de Boucherville, and the judge John Fraser were all either friends of the accused or allies connected with him through marriage or otherwise. The conclusions of their report-written in English and then translated into French – are even more revealing of the vices of the judicial system itself than they are of the obvious partiality of the members of the investigating committee; it asserted that “the whole complaint . . . is futile, ignorant, ungrateful, rash and scandalous.” Not content simply to reject Foucher’s complaints they went further, recommending that “as amends to the judge and to the government’s dignity” he be deprived of his “permit to pettifog . . . in order to set an example.” Things had reached such a point that the publisher of the Montreal Gazette, Fleury Mesplet, printed some letters from readers who, having followed the affair closely, could not refrain from making derisive comments on this travesty of justice.

To conceal this lamentable denial of justice Lord Dorchester invited Foucher to argue his case before a plenary meeting of the Legislative Council on 7 April 1791. The members of the council were then called upon to submit a conclusive report to the governor after a thorough examination of the whole dossier. It was not until 23 July that three reports – a majority one, a minority one, and one by the chief justice – were laid on the council table. The majority of the councillors (who constituted the French party) backed the committee’s conclusions, finding Foucher’s grievances “baseless, vulgar, and malicious.” Only a minority recognized that the plaintiff had indeed been prevented from practising his profession as a lawyer and had been treated “with unnecessary harshness.” For his part, the chief justice criticized Hertel de Rouville’s conduct but did not dare advocate that he be dealt with severely; such a recommendation would have risked the annulment of Hertel de Rouville’s commission as judge for the District of Montreal, and also might have deprived him of his right to sit on the Court of Common Pleas in Trois-Rivières (recently set up through an ordinance of 29 April 1790), as well as on that in Quebec, the various judges in office having recently been authorized to take turns in each of the province’s three districts.

Although Hertel de Rouville had succeeded in escaping severe sanctions, thanks to the established system, he had nevertheless been affected by the affair’s repercussions, which made him feel that he had been a victim of persecution. In the hopes of being “justified in the eyes of his sovereign” and of receiving “a striking token to avenge him for the insult as a [final] consolation before going to his grave,” he took the initiative of informing the Home secretary, Lord Grenville, of his unhappy lot as a poor 70-year-old who had been “slandered . . . and made a public spectacle.” He died less than a year later, without any consolation, and judging by the way in which his death was reported in the Montreal Gazette and the Quebec Gazette, it may be supposed that his departure occasioned little regret: “His Honour Mr. Justice Hertel de Rouville, one of the judges of the Court of Common Pleas, died on Sunday the twelfth inst. [12 Aug. 1792] between 7 and 8 in the evening.”

AN, Col., C11A, 80, pp.113–14 (PAC transcripts). ANQ-M, Greffe de Pierre Panet, 5 févr. 1767. ANQ-Q, Greffe de Nicolas Boisseau, 11 oct. 1741; NF 2, 34, f.88; 36, ff .69, 124. ASGM, Laïcs, H. PAC, MG 8, C10, 2, pp.1–3, 4–7, 404–7; MG 11, [CO 42], Q, 11, pp.149–51; 53, pp.202–573; MG 24, L3, pp.3896, 3904; RG 1, E 1, 1, pp.155–65; RG 4, A1, 31, p.39; 32, pp.1–3; RG 68, 89, f.112. PRO, CO 42/88, f.137. American archives (Clarke and Force), 4th ser., III, 1185–86, 1417. Pierre Du Calvet, Appel à la justice de l’État . . . (Londres, 1784), 90–91. [Louis] Franquet, “Voyages et mémoires sur le Canada,” Institut canadien de Québec, Annuaire, 13 (1889), 22, 113–14. Invasion du Canada (Verreau). [Francis Maseres], Additional papers concerning the province of Quebeck: being an appendix to the book entitled, “An account of the proceedings of the British and other Protestant inhabitants of the province of Quebeck in North America, [in] order to obtain a house of assembly in that province” (London, 1776). PAC Rapport, 1914–15, app.C, 48–51, 244–46; 1918, app.C, 17–18. Montreal Gazette, 5 May 1791, 16 Aug. 1792. Quebec Gazette, 16 Aug. 1792. P.-G. Roy, Inv. ins. Prév. Québec, II, 73; III, 37; Inv. jug. et délib., 1717–60, IV, 24–26; V, 11–12; Inv. ord. int., III, 90, 126, 135–36; Inv. procès-verbaux des grands voyers, V, 170. Turcotte, Le Cons. législatif, 75.

Burt, Old prov. of Que. [François Daniel], Histoire des grandes families françaises du Canada, ou aperçu sur le chevalier Benoist, et quelques families contemporaines (Montréal, 1867). Nearby, Administration of justice under Quebec Act. Cameron Nish, François-Étienne Cugnet, 1719–1751: entrepreneur et enterprises en Nouvelle-France (Montréal, 1975), 83–118. P.-G. Roy, La famille Jarret de Verchères (Lévis, Qué., 1908), 28. Sulte, Mélanges historiques (Malchelosse), VI, 131. Tessier, Les forges Saint-Maurice. P.-G. Roy, “Les grands voyers de la Nouvelle-France et leurs successeurs,” Cahiers des Dix, 8 (1943), 225–27; “L’hon. René-Ovide Hertel de Rouville,” BRH, XII (1906), 129–41; “René-Ovide Hertel de Rouville,” BRH, XXI (1915), 53–54.

Cite This Article

Pierre Tousignant and Madeleine Dionne-Tousignant, “HERTEL DE ROUVILLE, RENÉ-OVIDE,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 4, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed January 1, 2026, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/hertel_de_rouville_rene_ovide_4E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/hertel_de_rouville_rene_ovide_4E.html |

| Author of Article: | Pierre Tousignant and Madeleine Dionne-Tousignant |

| Title of Article: | HERTEL DE ROUVILLE, RENÉ-OVIDE |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 4 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1979 |

| Year of revision: | 1979 |

| Access Date: | January 1, 2026 |