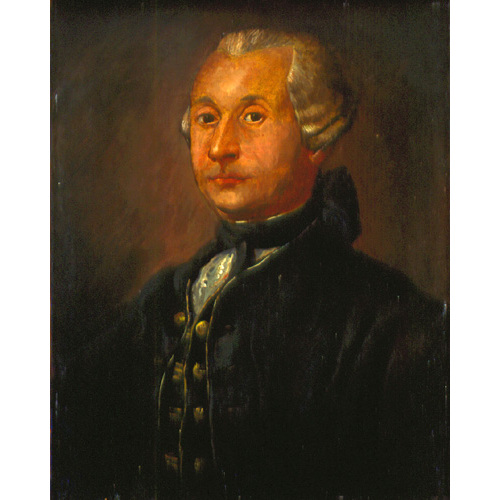

Source: Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

SALES LATERRIÈRE, PIERRE DE (he did not use his patronymic Fabre in Canada, taking the name of Jean Laterrière on his arrival, Jean-Baptiste in the early 1770s, Jean-Pierre most frequently between 1778 and 1788, and Jean-Pierre or Pierre de Sales Laterrière from 1789), doctor, commissary and inspector of the Saint-Maurice ironworks, seigneur, and author; b. in the 1740s in the Languedoc-Roussillon region of France; m. 10 Oct. 1799 Marie-Catherine Delezenne*, widow of Christophe Pélissier*, at Quebec, and they had three children; d. there 14 June 1815.

Pierre de Sales Laterrière is an enigmatic figure. Called by turns a strange fellow and a pathological liar, this adventurer from the south of France left memoirs, published in 1873, which historians have treated as “the account of the impostures and subterfuges” of a Gascon desperately anxious to carve a place for himself in Canadian society. In the present state of research it is difficult to separate truth from falsehood since the errors, contradictions, improbabilities, and abridgements in his account, whether deliberate or not, help to confuse issues and even tend to cast doubt on his identity.

Pierre de Sales Laterrière purported to be the son of a count from Languedoc, Jean-Pierre de Sales, a descendant of the famous house of de Sales which had given France a great many officers and the church a saint. He based his assertions on a baptismal record dated 23 Sept. 1747 which, although carefully presented as authentic, is impossible to trace. The historian Ægidius Fauteux* has established that he was the son of a man named Fabre from the diocese of Albi and that he reportedly adopted the surname of de Sales in the 1780s. Fauteux casts further doubt on the credibility of Laterrière. Relating in his memoirs his adventures from the time he left the family home until he arrived in the province of Quebec, Laterrière mentions studying naval mathematics in La Rochelle and medicine in Paris. In fact, he is believed simply to have left his birthplace in October 1765 at the instigation of his uncle Pascal Rustan, whose real name was Henri-Marie-Paschal Fabre, dit Laperrière. Rustan had been released at the end of April that year from the Châtelet, where he had been imprisoned in connection with the affaire du Canada. Laterrière, accompanied by his uncle, is believed to have gone to Paris via La Rochelle, then to England, and finally to Canada. He arrived at Quebec on 5 Sept. 1766.

Laterrière was about 19. By his own description he was naïve and frank, exuberant, and amazed by everything he had seen while sailing up the river. He was welcomed by Alexandre Dumas and entertained by a large number of friends to whom Rustan had recommended him. He spent the winter in Montreal, working as a clerk in one of Dumas’s stores. He frequently visited his aunt, Catherine Aubuchon, dit Lespérance, who lived at Longue-Pointe (Montreal) and who opened the doors of polite society to him: “During the winter, which lasts 8 months, the nights are spent in feasting, suppers, dinners, and balls. The ladies there play cards a great deal before and after the dances. All games are played, but the favourite is an English game called wisk [whist]. Billiards are very fashionable, and many are ruined by them.” In the spring Laterrière was back at Quebec; he remained in Dumas’s employ until the latter went bankrupt in 1769. Short of resources but not of imagination, Laterrière went off to the parish of Saint-Thomas (at Montmagny) to practise medicine with Jean-Bernard Dubergès. It would appear that, with little or no medical knowledge, he set out to learn the rudiments from Dubergès.

The association did not prove profitable. Laterrière was quite happy to accept the office of agent at Quebec for the shareholders of the Saint-Maurice ironworks in 1771. At the company store, located in Dumas’s house near the Lower Town market, Laterrière busied himself with selling, wholesale or retail, the products of the ironworks and sending the pig-iron to England. He restricted his medical concerns to treating “young men suffering from syphilis.”

“Of pleasing appearance, well-mannered, and with a passionate fondness for dancing,” according to his own assessment, Laterrière did not lack “amusements.” He had several love affairs, and only lack of money kept him from marrying Marie-Catherine Delezenne, daughter of the silversmith Ignace-François Delezenne*, whom he considered “very good-looking and witty.”

Satisfied with Laterrière’s services as commissary and as agent in various matters, Christophe Pélissier, the director of the Saint-Maurice ironworks, invited him to move to Trois-Rivières as works inspector: he would receive a salary of £125 a year, plus one-ninth of the profits. Laterrière left Quebec on 25 Feb. 1775. On 8 March Pélissier married Marie-Catherine Delezenne, who was in love with Laterrière but may have agreed to marry the 46-year-old widower at her father’s insistence. In the autumn Pélissier began to supply the American army, which was advancing towards Quebec, with guns, cannon-balls, shells, and various other items. Laterrière later claimed that he had not been aware of Pélissier’s dealings with the enemy until the end of March 1776, but this seems improbable. Bearing a note from Pélissier for the officer in command of the American troops besieging Quebec, he went there early in May to get merchandise. He was arrested by the British, imprisoned for several weeks, and then let go. He was back in Trois-Rivières at the beginning of June. The American army retreated. Worried about his own fate, on 7 June Pélissier fled for New York by way of the Richelieu. The following day the Americans were defeated at Trois-Rivières. Laterrière took over the running of the ironworks, possibly at Governor Guy Carleton’s express request. He began to live with Marie-Catherine, who gave birth to a daughter, Dorothée, on 4 Jan. 1778. Having failed in their attempt to separate the lovers, Marie-Catherine’s parents disinherited her on 4 Nov. 1780.

At that period the Saint-Maurice ironworks were a substantial enterprise. The region, flat and sandy, was “full of swamps and burnt lands, where the ore is located in veins . . . [and] yields 33 per cent pure and excellent iron.” The furnaces and forges were run on charcoal. Between 400 and 800 people worked “in the shop or in the woods, quarries, mines, and on the carts.” The company had “a store with goods and provisions,” and a “spacious house”; the workers stayed in “about 130 very clean, very liveable houses.” Year in year out the operation would bring in “10 to 15 thousand louis per seven-month season; expenses took two-thirds of it.” Laterrière was happy in the midst of the “little clan” at the ironworks. “The people [were] kind,” there were plenty of holidays, and the establishment had numerous visitors. On 6 Oct. 1777, on payment of £900, Laterrière became a shareholder in the enterprise. The following year Pélissier made the lease over to Dumas. Laterrière bought the Île de Bécancour, while continuing to run operations at, the ironworks until October 1778. In July he had gone with Marie-Catherine to meet Pélissier, who was passing through Quebec to settle the company’s accounts. Pélissier had Marie-Catherine shut up illegally, but she managed to slip away and hide on the Île de Bécancour.

In the autumn Dumas offered Laterrière, who had become the “manager and director” of the ironworks, the opportunity to enter into partnership to run them on a fifty-fifty basis, and in January 1779 they came to an agreement. To make this deal Laterrière had to let Alexis Bigot, dit Dorval, a habitant from the seigneury of Cap-de-la-Madeleine, have the Île de Bécancour on 10 February, in exchange for a house and lot at Trois-Rivières and 6,500 livres. That month, however, Laterrière was arrested. He was suspected of having incited Michel Delezenne, Marie-Catherine’s brother, and an employee, John Oakes, to go to meet the Americans and pass on information to them. In the preliminary investigation conducted by Conrad Gugy*, François Baby, and Louis-Joseph Godefroy* de Tonnancour, Oakes exonerated Laterrière, but Delezenne heaped accusations upon him. It was a confused affair. Laterrière saw in it a plot hatched by Pélissier before he had left permanently for France; he thought that its success had been assured through Haldimand’s connivance and the complicity of some unscrupulous and ambitious people in Trois-Rivières: the vicar general Pierre Garreau*, dit Saint-Onge, Godefroy de Tonnancour, the judge René-Ovide Hertel* de Rouville, and Marie-Catherine’s father. A reading of all the documents related to the affair makes the hypothesis of a conspiracy seem flimsy but the accused man’s innocence plausible. From the beginning his cohabitation alienated the investigators’ sympathy. His version tallied on certain important points with the depositions made by Oakes on 24 February and his own farm labourer on 4 March. Later Michel Delezenne wrote to his father “that what he said at the time of his interrogation concerning Laterrière was said because he was afraid.” Moreover, in January 1780 a deposition by Louis Guillon, another of Laterrière’s employees, confirmed that of Michel Delezenne, adding details. An embarrassed Haldimand, confident none the less that the investigators “will have done justice to the accused as to the accusers,” ordered that the prisoner be taken to Quebec. In March 1779 Laterrière was locked up in the prison, where Valentin Jautard*, Fleury Mesplet*, and Charles Hay* soon joined him. While philosophizing and quarrelling with his companions Laterrière was able to transact business through agents. The request he sent Haldimand from prison for the lease to the Saint-Maurice ironworks reveals that he was thoroughly familiar with foundry techniques. In 1780 he bought a house at Quebec and had his furniture moved there; two years later he sold his house in Trois-Rivières. Nathaniel Day worked in his name at settling accounts with Dumas.

Early in November 1782 Laterrière regained his freedom, but he had to leave Canada “until peace came.” The sailing season was nearly over. He would have liked to take ship for Europe, but the only one he found in port was a brig bound for Newfoundland. He spent the winter at Harbour Grace with his daughter. In the spring of 1783 he hired a brig together with William Hardy, a merchant who had a cargo but did not know where to sell it, and they sailed for Quebec, taking time along the way to do some trading in the gulf. Once at Quebec, Laterrière decided on his friends’ advice to terminate his association with Hardy and rejoin Marie-Catherine and his friends in Bécancour. He set her up “at the head of a little store” at Saint-Pierre-les-Becquets (Les Becquets), settling down himself at Bécancour, where he practised medicine, did a little trading, and contracted to have “timber for masts and firewood” cut on a woodlot that he had bought in Gentilly (Bécancour). Business was slow.

In the autumn of 1783 Laterrière’s inventive mind led him to carry out a plan that on the surface was quite hare-brained. He built a house on a sleigh drawn by two horses. It was a pedlar’s sleigh, “covered and quite solid; up front was a well-stocked store; in the middle and crosswise, a cupboard to hold a dispensary and surgical instruments; at the rear, a small room with a stove and chests containing a bed, dishes, and supplies.” During the winter he went from parish to parish as far as Saint-Hyacinthe to offer medicaments, merchandise, and his services as a doctor. The experiment aroused people’s curiosity but did not turn out to be profitable. In the spring of 1784 Laterrière settled at Gentilly with his family on a farm that he had bought for 600 livres the previous autumn. He lived in a house 24 feet square which he called “the château-villa of Belle-Vue.” He had some success farming, but met with none speculating in wood for masts and firewood. He survived thanks to his income from practising medicine and his investment in bonds. Late in 1787 he settled at Baie-du-Febvre (Baieville), on the farm of Delezenne, who had been reconciled with his daughter. His reputation as a doctor kept on growing and he made “a lot of money.”

The future was promising, until Laterrière learned that a new law required doctors to produce their diplomas and appear before the Medical Board. Since he had no diploma (or had lost it), the examiners made Laterrière return to his books, which led him to register at Harvard College in Boston in the autumn of 1788. There he studied medicine with Benjamin Waterhouse, and anatomy and surgery with John Warren. On 1 May 1789 he took his examination in medicine, and a few weeks later he presented a thesis on puerperal, fever. He left Boston on 15 June, and at Quebec on 19 August he successfully took a new examination. After his return to Baie-du-Febvre the number of his patients grew rapidly. He travelled around in the neighbouring parishes, and eventually extended his practice as far as Trois-Rivières and the parishes “north of Lac Saint-Pierre.” He lived comfortably and speculated in real estate. On 16 Sept. 1790 he bought three lots in Trois-Rivières; he also purchased a house there belonging to Louis-René-Labadie Godefroy de Tonnancour in which he set up practice, probably in the spring of 1791. He was appointed the prison doctor, and in October in the presence of his colleagues he did a dissection on the body of a woman who had just been hanged. This session in anatomy alienated the local population, and in the spring of 1792 he returned to his house at Baie-du-Febvre, where his son Marc-Pascal* was born on 25 March.

Eager to assure his children of a sound education, in May 1799 Laterrière went with Dorothée and his elder son, Pierre-Jean*, to live in Quebec on Rue de la Montagne. He practised medicine, surgery, and pharmacy, and kept “a dispensary for the gentlemen of the art and other private individuals.” Marie-Catherine joined him in the autumn, and on 10 Oct. 1799 he married her in the cathedral of Notre-Dame at Quebec, in the presence of the coadjutor designate Joseph-Octave Plessis*. Laterrière was well received by his colleagues. He was one of the rare individuals to be a qualified doctor licensed to practise surgery, pharmacy, and obstetrics as well.

On 24 Feb. 1800 Dorothée married François-Xavier Lehouillier, who according to Laterrière was homosexual. The marriage turned sour, to the great chagrin of Laterrière; deeply affected by his daughter’s misfortunes, he returned to live in Trois-Rivières around 1804. But the dangers facing his daughter, who was being ill treated by her husband, brought him back to Quebec in 1805. The matter ended in a separation.

During his short stay in Trois-Rivières Laterrière had renewed contact with the Saint-Maurice ironworks. In May 1806, with Nicholas Montour and ten other partners, he formed Pierre de Sales Laterrière et Compagnie for the purpose of acquiring the lease to the ironworks. He kept 6 of the 32 shares for himself. A disagreement among the partners led to the formation of another company with a capital of £10,000, of which he became the director and ironmaster. The government, however, granted the lease to Mathew Bell*, and the new company was dissolved.

On 26 July 1807 Pierre de Sales Laterrière sailed for Europe to settle a matter of inheritance. War prevented him from going to France. He stayed in Portugal and England, whence he returned in June 1808 with merchandise which he valued at £3,000 and which Dorothée sold in the store she kept in Quebec. This deal brought Laterrière such substantial profits that he was able to send his elder son to study medicine in England and the younger one to Philadelphia; it also enabled him to purchase the seigneury of Les Éboulements on 31 Jan. 1810. “Old and infirm,” Laterrière was conscious that “his role was finished.” Around 1812 he left his apothecary’s shop and his medical practice to his son Pierre-Jean, who later went into partnership with his younger brother, and then he retired to Les Éboulements. On 14 June 1815 he died at Quebec, in his son Marc-Pascal’s home: he was buried two days later in the crypt of Notre-Dame.

[Pierre de Sales Laterrière is the author of A dissertation on the puerperal fever . . . (Boston, 1789) and Mémoires de Pierre de Sales Laterrière et de ses traverses, [Alfred Garneau, édit.] (Québec, 1873; réimpr., Ottawa, 1980). Extracts from the latter work were published in Écrits du Canada français (Montréal), 8 (janv. 1961): 259–337; 9 (avril 1961): 261–348. p.d. and j.h.]

Arch. de l’univ. Laval (Québec), 298/17. PAC, MG 8, F131. Quebec Gazette, 1 Dec. 1808. Charland, “Notre-Dame de Québec: to nécrologe de la crypte,” BRH, 20: 279. “Collection Haldimand,” PAC Rapport, 1888: 169, 809, 818, 984–89. J. [E.] Hare, Les Canadiens français aux quatre coins du monde: une bibliographie commentée des récits de voyage, 1670–1914 (Québec, 1964). M.-J. et G. Ahern, Notes pour l’hist. de la médecine. H.-R. Casgrain, Œuvres complètes (3v., Québec, 1873–75), 1: 64–71. Sulte, Mélanges hist. (Malchelosse), 6: 123–68; 7: 84, 94–95, 98, 104. J.-P. Tremblay, La Baie-Saint-Paul et ses pionniers ([Chicoutimi, Qué.], 1948). Ægidius Fauteux, “La thèse de Laterrière,” BRH, 37 (1931): 174–75. Gérard Malchelosse, “Mémoires romancés,” Cahiers des Dix, 25 (1960): 103–44. Benjamin Sulte, “Le docteur Laterrière,” Le Pays laurentien (Montréal), 1 (1916): 35–38. Albert Tessier, “Les Anglais prennent les forges au sérieux,” Cahiers des Dix, 14 (1949): 165–85.

Cite This Article

Pierre Dufour and Jean Hamelin, “SALES LATERRIÈRE (Fabre), PIERRE DE (Jean (Jean-Baptiste, Jean-Pierre) Laterrière),” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 5, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed December 31, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/sales_laterriere_pierre_de_5E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/sales_laterriere_pierre_de_5E.html |

| Author of Article: | Pierre Dufour and Jean Hamelin |

| Title of Article: | SALES LATERRIÈRE (Fabre), PIERRE DE (Jean (Jean-Baptiste, Jean-Pierre) Laterrière) |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 5 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1983 |

| Year of revision: | 1983 |

| Access Date: | December 31, 2025 |