Source: Link

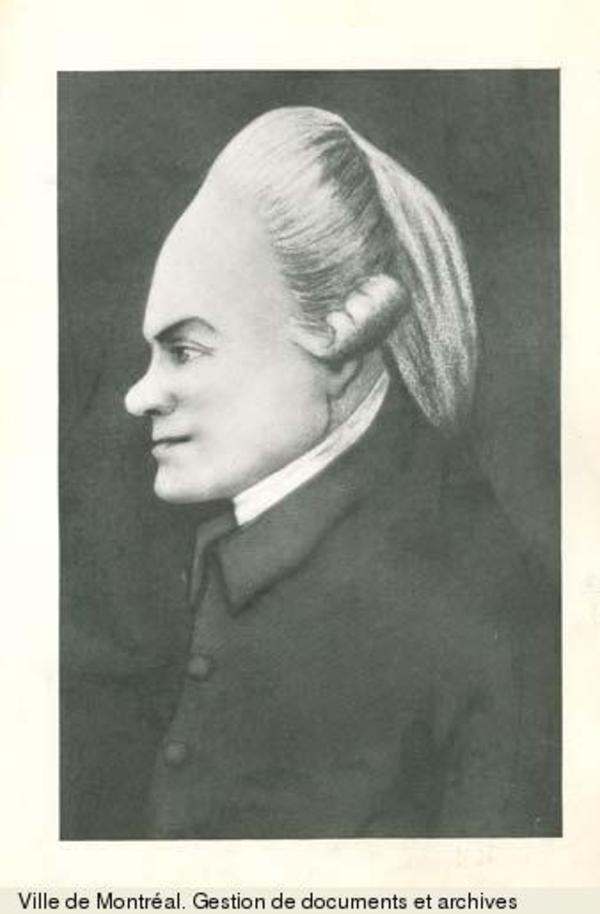

MABANE, ADAM, physician, judge, and councillor in the province of Quebec; b. c. 1734, probably in Edinburgh, Scotland; d. unmarried, 3 Jan. 1792 at Sillery, Lower Canada.

The first 26 years of Adam Mabane’s life remain obscure; one source gives his mother’s name as Wedel, asserts that his father, although a Protestant, had refused to swear allegiance to the Hanoverians, and claims for him relationship to James Thomson, author of The seasons. Mabane seems to have attended the University of Edinburgh but did not graduate; the amount of medical training he received remains in doubt. As a surgeon’s mate in Amherst’s army he entered Quebec from New York in the summer of 1760.

There is little evidence that Mabane arrived with any of the advantages of birth or connection that would mark him out for preferment; only his appointment as assistant to the surgeon at the Quebec military hospital elevated him to commissioned rank in the army. At the same time he began a private medical practice which was to continue throughout his life and which became the source of much of his popularity. How skilful he was as a physician was always a matter of dispute among his political friends and enemies; the latter described him as antiquated in his methods by the time he had reached his thirties, but, surprisingly, they seldom stressed the inadequacy of his early training. His willingness to sacrifice his own comfort, his casualness about payment, and his sympathy for his patients, many of whom were Canadians, gave him a reputation for unselfishness, devotion, and honesty that constituted a genuine appeal to the emotions of many in the colony, including a number who held important offices in Quebec in the three decades after the conquest. These powerful friends, and less demonstrably this popular affection, made possible a political and judicial career for which Mabane had no training whatever.

That career began in August 1764 when Governor Murray appointed him to the Council of Quebec; in the following month he became a judge of the Court of Common Pleas for the district of Quebec. At first there was no payment for the judicial duties, and the new judge pointed out the financial loss he suffered in curtailing a lucrative medical practice to undertake other responsibilities. During the two years of Murray’s administration Mabane became identified as the governor’s constant supporter in the triangular feud that developed between Murray, the English merchants, and the Montreal military authorities. Mabane may have exacerbated the feud by his own partisanship and tactlessness in denying the right of the brigadier of the Northern Department, Ralph Burton*, to inquire into his expenses as surgeon of the Quebec garrison; Murray, however, regarded Mabane as the victim of the conflicting interests of the civil and military authorities. After Murray’s departure for England on 28 June 1766 Mabane, because of the support he had shown the governor, came to symbolize the political position of his administration. Murray, however, was no longer present to offer protection.

Lieutenant Governor Guy Carleton* arrived in the colony on 22 Sept. 1766, determined to dissociate himself from the disputes of the previous régime. He chose to exclude Mabane, among others, from the first meeting of councillors held on 9 Oct. 1766. Mabane’s participation in the ensuing remonstrance, and his unwise visibility in the protest against the refusal of bail in a celebrated court case, marked him out for dismissal. Compared to Paulus Æmilius Irving, who was dismissed at the same time and for the same reasons, Mabane was extremely vulnerable, although Carleton, in spite of threats, did not go so far as to secure his dismissal from the bench. Mabane thus continued in the Court of Common Pleas, continued to protest his removal from council, and became a major property owner in Sillery, near Quebec, with the purchase of Woodfield, an estate once owned by Pierre-Herman Dosquet. By the early 1770s, with Murray’s return no longer a threat, there seems to have been some easing of the tension between Governor Carleton and Mabane; Carleton was able to see Mabane’s position in the colony as a potential support for his own. Mabane’s agreement with the political principles of the Quebec Act, horror at the increasing turbulence in the American colonies, and commitment to the British cause were all consistently evident, and his convictions were rewarded with an appointment to the new Legislative Council in 1775. Several Canadians were appointed to the council at the same time, and although few of them assumed positions of leadership, Mabane’s influence was enhanced by their support. These councillors reinforced the strength of the French party, a group headed by Mabane which had emerged during Murray’s administration and which claimed to speak for and protect the rights of a Canadian majority against English merchants who wished to destroy both French traditions and British imperial power.

Mabane’s influence in judicial matters also increased during the 1770s. On 26 April 1775, four days before the implementation of the Quebec Act, which would establish a new judicial organization, Carleton reappointed the judges of the former courts and added two new names, Jean-Claude Panet and René-Ovide Hertel de Rouville. It was popularly believed that these two looked to Mabane for guidance. With his fellow judge and councillor, John Fraser, Mabane was a member of the committee of council that drafted new ordinances for the establishment and regulation of civil and criminal courts in the province. For criminal cases, a court of king’s bench, presided over by three commissioners in the absence of a chief justice, was established, and for civil cases the province was divided into two districts, Quebec and Montreal, with a court of common pleas in each. A court of appeals, composed of the governor, lieutenant governor, or chief justice, and five members of the council, served both districts. These ordinances became law in early 1777, and although they were to be in effect for a two-year period only, the system was continued until 1786. When Peter Livius assumed office as chief justice he protested in vain against the arbitrary proceedings in the Court of Appeals and the unchallenged power of the governor and council in judicial affairs. His countervailing influence was removed in 1778 when Carleton, with Mabane’s enthusiastic support on this occasion, chose to dismiss him. Livius was able to win his case for reinstatement, but he never returned to Canada. For the next eight years Mabane performed many of the duties of chief justice and came to believe that he would secure the appointment.

The continuance of the American war, the legacy of Carleton’s policies, and the character of Frederick Haldimand, who became governor in 1778, all combined to make Adam Mabane a virtual mayor of the palace during these years. Haldimand relied upon Mabane as the most experienced man in the colony; he found his company congenial, his eccentricities lovable, and his financial position worthy of sympathy and such assistance as a governor could bestow. The most passionate critic of the Haldimand-Mabane association was Pierre Du Calvet, charged with treason in 1780 and imprisoned for almost three years. That Du Calvet, whose guilt was beyond doubt, considered himself a victim of the governor and his council does not invalidate all his criticisms of the government. His character sketch of Mabane, with his “habitually grimacing expression,” bears the stamp of truth, and no better description of the laws of the period has been found than Du Calvet’s “masquerade of alleged French jurisprudence.”

The dangers inherent in placing the rights of all citizens within the discretionary powers of the governor and the judges were forcibly illustrated by the case of Haldimand v. Cochrane, where the plaintiff was the governor of the colony and the judge, Mabane, his closest adviser. In the years of Mabane’s greatest power, Quebec was operating outside any principle of the rule of law, outside any legal system known to England or France, guided only by Mabane’s personal concept of justice in specific cases. His prejudices were well known. The poor received more sympathy than the rich, and the one crime that was never forgotten, no matter how irrelevant it might have seemed to the case before the courts, was any failure in loyalty to the crown, especially during the American invasion of 1775–76. Such a bias was even more significant in view of Mabane’s close association with other judges, most of them lacking his experience, and with some of the lawyers, such as Alexander Gray, who were pleading cases before him by the 1780s. Only the personal integrity of governor and judges prevented this lack of system from degenerating into intolerable tyranny.

Within the Legislative Council any attempt to break the stranglehold of the French party had little chance of success before 1784. Governor Haldimand used the American war as a reason for consulting only part of his council on occasion, even though the practice had been condemned by the home government. Any question of revising legal ordinances or considering the plight of prisoners detained without trial was easily postponed by the votes of Mabane and his supporters in council, and their advice also determined which petitions and remonstrances reached council for consideration.

As soon as peace with the United States was signed it became evident that, in some matters at least, the French party had been sincere in its claim that postponement was merely a war measure. In April 1784 one of the party members introduced a motion, unanimously supported by the council, to introduce the English law of habeas corpus. But when William Grant* moved that “the common and statute law of England insofar as it concerns the liberty of the subject” be instituted – a resolution which would have extended habeas corpus to civil cases as well as criminal ones – Mabane’s group opposed the motion, since it went against the principles of the Quebec Act, and united to defeat it by a vote of nine to seven. Supporting the substantial minority was Lieutenant Governor Henry Hamilton, who became responsible for the administration of the province on the departure of Haldimand a few months later. Hamilton was critical of the position adopted by the French party, while Mabane believed that the implementation of Hamilton’s policies would involve the destruction of the Quebec Act, which he regarded as a charter, and introduce dangerous American ideas of government. Hamilton proceeded to admit for debate, and perhaps even to encourage, petitions which Mabane would have been able to suppress in earlier years. For the first time ordinances were passed with Mabane registering his dissent from the majority; in his private correspondence he denounced his opponents as “wasps and vipers,” in a style reminiscent of Governor Murray’s dispatches of two decades before.

Late in 1786 Carleton, raised to the peerage as Lord Dorchester, began his second term as governor of Quebec, and with him came a new chief justice, William Smith. It soon became apparent that the tribulations of the French party under Hamilton had been no temporary discomfiture. The year 1787 marked the climax of debate in the council, and the fierce battles of that year were far more important in their cumulative effect than any single piece of legislation passed or committee report accepted. In isolated engagements the French party could still muster the larger force, and on at least one occasion the law officers of the crown found Mabane’s legal argument more convincing than that of the chief justice. Nevertheless, the political power of the French party was crumbling. Dorchester divided the council into committees to consider such questions as agriculture, colonization, trade, and education. Since several of Mabane’s opponents were senior to him on the council, he rarely served as chairman on any of these committees or cast the deciding vote that was so often required. More important, the French party had not developed new policy in any of these areas during the previous decade; they chose to defend the Quebec Act as the charter of all freedoms, whatever the specific subject of debate.

By far the most important of the committees from Mabane’s point of view was the one investigating the administration of justice after 1775. In the midst of debate over conflicting motions before the council such a lengthy and public attack on the conduct of the judges had been made that on 18 May 1787 Dorchester had ordered a somewhat reluctant chief justice to undertake the investigation. There was no lack of evidence concerning the inadequacies and complexities of the judicial system, but the personal attack on Mabane and the ridicule and humiliation to which he was subjected aroused much popular sympathy. Neither side in the political dispute emerged from the affair with much credit, but Mabane remained as firmly entrenched as ever in the common pleas and in popular esteem. When the time came for appointments to the new Executive and Legislative councils established under the Constitutional Act of 1791, his name could not be ignored. His death occurred, however, before he had been sworn into office. It was only then that his opponents could effect real change, as Smith’s comment on the news of his death made clear: “Mr. Mabane having made a vacancy in the two councils and in the Common Pleas Bench, on the 3rd instant, I beg leave to suggest that his death, and the resignation, hourly expected, of Mr. de Rouville, will open a door for the amendment of the jurisprudence of the province without detriment to individuals.”

In contrast to the coldness of the Smith letter there was the warmth of friendship many felt for Mabane and his sister Isabell. John Craigie*, Henry Caldwell*, and Dr James Fisher* acted on her behalf to settle her brother’s estate. His creditors were mollified to some extent by the sale of his books and furniture, and the immediate renting and eventual sale of Woodfield. It was found, however, that the doctor’s possessions were insufficient to meet his debts.

Such a career as Mabane’s inevitably evokes powerful responses. Smith’s frustration and Du Calvet’s exaggerated attacks had their echoes in later critical evaluations of Mabane. Nearly a century after his death, however, Abbé Louis-Édouard Bois* attempted to revive the memory and vindicate the reputation, portraying Mabane as the victim of persecution among his own people because of his sympathy for the Canadians. Now it would appear that Mabane’s 30-year defence of what he conceived to be the Canadian interest is significant in that it helped to establish the framework within which early French Canadian nationalists were to operate. His career, moreover, offers an insight into the nature of 18th-century society in Canada, both through the record of his personal acquisition of power and through the social and political concepts he defended.

BL, Add. mss 21661–92. PAC, MG 23, GI, 5; GII, 1, 15, 23. Docs. relating to constitutional history, 1759–91 (Shortt and Doughty; 1918). Pierre Du Calvet, Appel à la justice de l’État . . . (Londres, 1784). E. [M.] Arthur, “Adam Mabane and the French party in Canada, 1760–1791” (unpublished ma thesis, McGill University, Montreal, 1947). [L.-É. Bois], Le juge A. Mabane, étude historique (Québec, 1881). Neatby, Administration of justice under Quebec Act; Quebec.

Cite This Article

Elizabeth Arthur, “MABANE, ADAM,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 4, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed December 20, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/mabane_adam_4E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/mabane_adam_4E.html |

| Author of Article: | Elizabeth Arthur |

| Title of Article: | MABANE, ADAM |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 4 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1979 |

| Year of revision: | 1979 |

| Access Date: | December 20, 2025 |