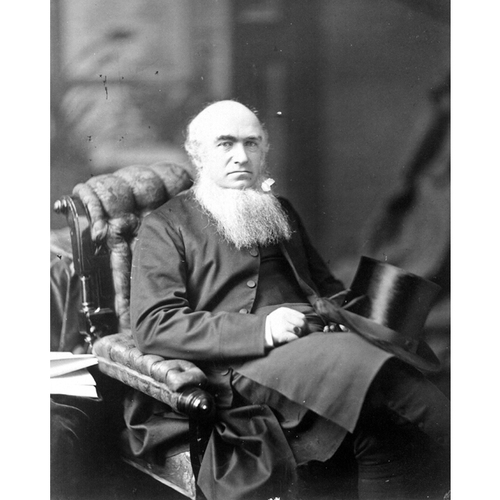

Source: Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

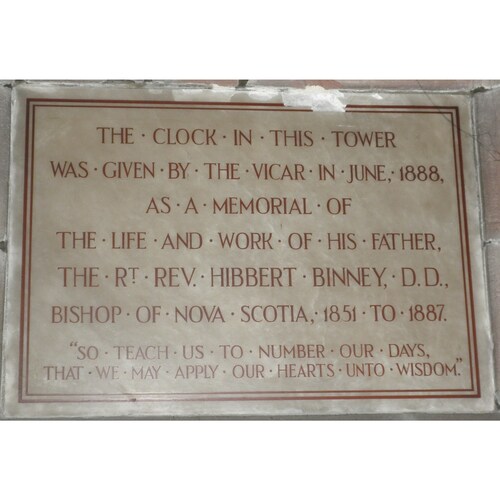

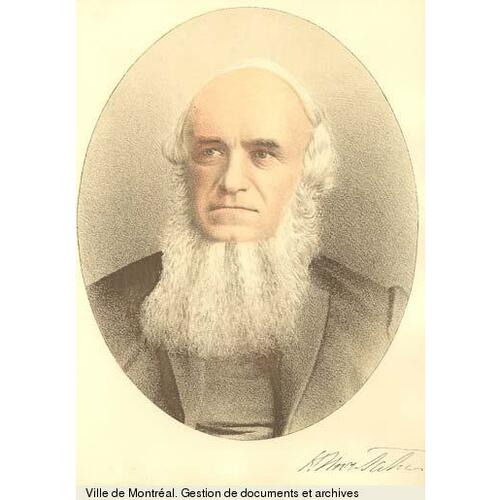

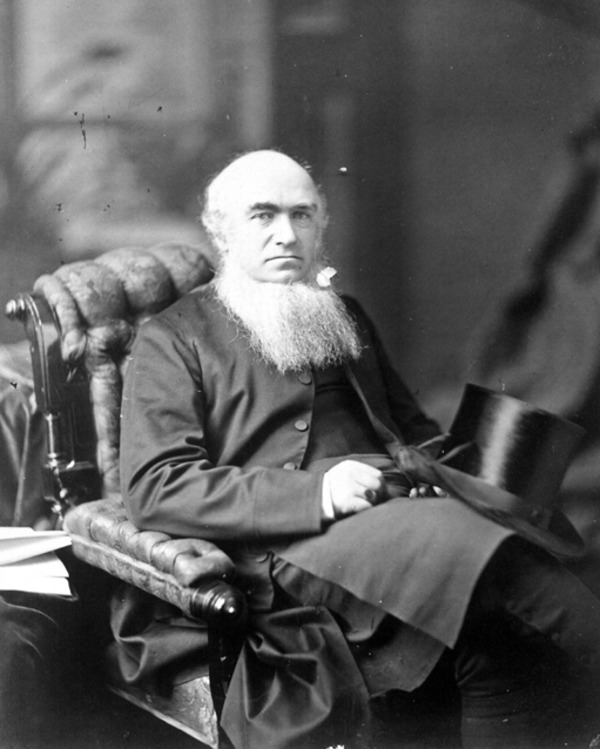

BINNEY, HIBBERT, Church of England bishop; b. 12 Aug. 1819 in Sydney (N.S.), son of the Reverend Hibbert Binney and Henrietta Amelia Stout; d. 30 April 1887 in New York City.

The Binney family had emigrated to New England late in the 17th century, and in 1753 Jonathan Binney* arrived in Nova Scotia where he became a member of the first House of Assembly and later a councillor. Jonathan’s son, the Reverend Hibbert Binney, was rector of St George’s Church in Sydney, Cape Breton, at the time of his son’s birth in 1819, but in 1823 left for England and by 1838 was rector of Newbury, Berkshire. At age 19 the younger Hibbert entered King’s College, London, and in 1842 graduated ba from Worcester College, Oxford, with 1st class honours in mathematics and 2nd class honours in classics. Hibbert followed his father into the ministry, being ordained deacon by the bishop of Oxford in 1842. In the same year he was appointed a fellow of Worcester College. He took his ma in 1844, was appointed tutor in 1846, and in 1848 became bursar of his college. At Oxford he was influenced by the Oxford Movement which was challenging the traditionally Erastian status of the established Church of England and which asserted the independence of the church from the state by emphasizing that the church’s authority was based on Catholic order and tradition as it had been preserved in the Book of Common Prayer.

When the Anglican bishopric of Nova Scotia became vacant following the death of John Inglis* in October 1850, there was considerable feeling in the colony that laymen should have a part in choosing the next bishop. Many thought that he should be a Nova Scotian, and the fact that Hibbert Binney had been born in the colony argued for his appointment. In March 1851 Binney was named bishop by the imperial government and consecrated in London by the archbishop of Canterbury and the bishops of London, Oxford, and Chichester. There is some reason for believing that Joseph Howe* had advanced Binney’s cause to Earl Grey, the colonial secretary, even though Binney would not have known much about missionary life in a colonial diocese. His father had spent most of his life in the colony and he belonged to an old and established Nova Scotia family, but Hibbert had left Nova Scotia at age four and had been educated as an English gentleman.

Thus Bishop Binney, steeped in Tractarian ideas, was sent at age 31 to a diocese characterized by latitudinarian and congregational sympathies. Of no such persuasion himself, he held, like his teachers at Oxford, that the Church of England contained within its tradition the truth concerning Catholic authority and spiritual grace. Coupled with this belief was an historical and theological conviction of the nature and power of the episcopal office. Bishop Binney firmly held that the church, being God’s chosen instrument for dealing with his people, was unchangeable, and must remain firm and steadfast against all popular whims and fashions. As far as he was concerned, the church was divine and holy and, as such, had a unique role to play in the world, a role no other institution could fill. Such a concept involved a universal organization and one which could not compromise with local traditions. He would allow for parochial variations in small matters only, and would not permit any serious breach of ecclesiastical law or doctrine.

Coupled with his conception of a divinely founded institution was the opinion that the church should not be restrained by any civil authority, and he often pointed out the evils of the English establishment. The only proper authority ordained of God for governing his church was the bishop, who, as father in God, ordered the affairs of the church. He warned Nova Scotia Anglicans against the dilution of episcopal doctrine arising out of the institutional chaos rampant in the Nova Scotia church. He was an able scholar and his ideas were essentially Catholic and were steeped in the ancient traditions and thought of the Greek and Latin fathers of the church. They infused a foreign concept of worship into the rationalist and latitudinarian theories of the Nova Scotia church. Throughout his episcopate he attempted to inculcate his ideas by diplomacy and gradual teaching. He tried to avoid direct confrontation, but this was not always possible. His first step was to curb the power of local parishes. A major move toward this end would be the establishment of a diocesan synod under the guidance of the bishop.

Throughout the Anglican communion there was a general movement toward the formation of synods and convocations composed of clergy and laity to govern church affairs. Bishop John Inglis had stated that he thought this movement would cause division in the church and should be discouraged. The rural members of the Church of England in Nova Scotia were not accustomed to governing themselves, and the wealthy parishes in Halifax and the more prosperous towns in the Annapolis valley and the south shore felt a synod would give the smaller rural parishes an unprecedented voice in the decision-making processes of the Nova Scotia church. Bishop Binney, an advocate of well-ordered local church government, attended a meeting of bishops in London in 1853, which included Bishop Edward Feild* of Newfoundland and the archbishop of Canterbury, to discuss the problem. They wanted the imperial parliament to pass an act which would enable the colonial dioceses to govern themselves. However, that year the House of Commons defeated the Colonial Church Bill advanced by William Ewart Gladstone, after it had been passed in the House of Lords, because it felt that incorporation of synods in the colonies should be dealt with in the colonial legislatures.

Bishop Binney summoned his clergy and two delegates from each parish to a meeting in Halifax on 12 Oct. 1854 “in order that the Members of the Church may decide for themselves whether they will hold periodical Assemblies or not.” Churchmen in Halifax suggested such a “convocation” would tend to strengthen the power of the bishop and that the whole design was a Tractarian plot. The old, established parishes of St Paul’s and St George’s in Halifax, with such influential members as Chief Justice Brenton Halliburton* and Henry Hezekiah Cogswell*, met in advance and decided not to support the proposal for a synod. Above all, they feared the desire in the rural parishes for a say in the affairs of the diocese. Despite this opposition, delegates from 23 of 36 parishes met in Halifax and decided “to hold periodical assemblies of the Clergy and Laity in this diocese” and to frame a constitution for a synod. On 11 Oct. 1855, with the older parishes maintaining a boycott, the parish delegates accepted a constitution giving the bishop the power of veto over all synodical measures. A third meeting held a year later, with only 12 of 50 parishes not adhering, gave a unanimous expression of loyalty to Bishop Binney. That year St Paul’s in Halifax threatened to dismiss its curates, Edmund Maturin* and William Bullock*, if they attended the diocesan meeting.

In 1860, after spirited discussion, the diocesan assembly approved a proposed bill to incorporate the synod, provide for its organization, establish a system of ecclesiastical discipline over parishes and clergy, and ratify the episcopal veto. On 23 Feb. 1863 the bill was presented to the House of Assembly for approval, but on 2 March St George’s in Halifax presented a petition condemning the provision for an episcopal veto. Binney, wary of opposition from both Anglicans and non-Anglicans, attempted to create a united Anglican front against the bill’s opponents. But to achieve unity it was necessary to amend the bill to guarantee the right of parishes to nominate their own rectors and not to belong to the synod if they did not wish. This amended bill was passed in the assembly but not the Legislative Council, which felt the measure would create further dissension in the Church of England because of the intense opposition to Binney’s views. Undaunted, Binney presented another bill which was passed on 29 April 1863; it incorporated the synod but did not confer on it any spiritual jurisdiction over parishes which did not choose to belong to it, nor did it extend to the bishop any coercive power to establish a form of worship. The diocese was divided into eight rural deaneries, and finally in 1878 St George’s and St Paul’s joined the synod, which continued with the episcopal veto. The opposition to Binney was similar to that encountered by other Canadian bishops, but he had accomplished his reorganization of the diocese with himself and the synod firmly in control.

But the church in Nova Scotia in order to be self-governing had to be financially self-supporting; it was not when Binney arrived in 1851. Anglican King’s College at Windsor lost its favoured status in 1851 when on 7 April the provincial legislature passed an act to discontinue its preferential grant, though it continued to receive grants equal to those given to other denominational colleges. Still, the church’s only institute of higher learning, founded in 1789, looked as if it might collapse. From 1851 to 1861 Binney and the Reverend George William Hill campaigned both in Britain and in Nova Scotia to raise an endowment for the college. With this campaign and with the reconstitution of the board of governors as “Friends of the College,” an endowment was established by 1861. But throughout Binney’s episcopate King’s was plagued by the unwillingness of local Anglicans to support it, lapses in discipline, and loss of scientific equipment, which finally led to the resignation of John Dart, the president, in 1884. In 1881 the provincial government had threatened to withdraw financial support from all the denominational colleges if they would not form a provincial university in Halifax centred around Dalhousie. But Binney managed to rally enough support locally and in Britain for Canada’s oldest English-speaking university to reopen in 1885 with the Reverend Isaac Brock* as president and Charles George Douglas Roberts* as one of its two professors.

Unlike the Methodists, Baptists, Presbyterians, and Roman Catholics in Nova Scotia, members of the Church of England were not accustomed to supporting their own church. From the days of Bishop Charles Inglis*, the diocese had been almost totally subsidized from England by the Society for the Propagation of the Gospel. On 1 Dec. 1850 the archbishop of Canterbury informed Binney that the SPG could no longer support the church in the colony and that money from England would be used instead for new missions in Africa and India. By 1860 Nova Scotia Anglicans still had done little to support their church, and Binney, this time in alliance with wealthy Haligonians, proposed an endowment scheme for the support of the diocesan clergy. Opposition came from rural parishes, especially that of Mahone Bay led by its rector, the Reverend William H. Snyder. Though gradually the people of the diocese began to contribute, Binney in 1870–71 repeatedly wrote to the SPG despairing of the unwillingness of the people to give support and of the harsh consequences of SPG policies. After a long struggle the Church Endowment Fund reached the point in 1872 where it could be used, and by 1880 the financial position of the diocese was secured.

Binney also wanted to improve the religious life of his diocese by emphasizing the sacramental life of the church. He frequently admonished his clergy to celebrate the Eucharist often and to emphasize the full theological significance of the offertory in the liturgy. He disliked the puritan and Calvinist leanings of the Nova Scotia clergy and reminded them to follow Anglican practice as set out in the Book of Common Prayer. This led him into difficulties with his clergy, in particular with the Reverend James Cuppaidge Cochran* of Halifax, who refused to give up his black Geneva gown for a white surplice, and also with the Reverend George William Hill, rector of St Paul’s, Halifax, after 1865. In 1866 Hill was to attack the bishop publicly for destroying the Protestant Reformed faith of the Church of England. Binney took his cathedra out of St Paul’s and on 21 Oct. 1864 established St Luke’s, Halifax, as the diocesan cathedral. There Binney maintained high standards of worship, aided by the dean of the diocese, William Bullock, a Tractarian sympathizer.

During his episcopate Binney’s Tractarian ideas gradually became accepted by the clergy and laity of the diocese as a whole, but his chief Tractarian venture was at Charlottetown. On 22 Aug. 1869 he preached at the opening service of St Peter’s Cathedral, founded by him as a cathedral church for Prince Edward Island outside the normal jurisdiction of the parish church of Charlottetown, St Paul’s. Here, as in Halifax, Binney appointed as his chaplain a devoted follower of the Oxford Movement, the Reverend George Wright Hodgson. From Charlottetown the Tractarian school planned an Anglo-Catholic mission to the whole diocese of Nova Scotia. Hodgson had close connections with Tractarians in Saint John, N.B., Montreal, and England, and his influence was felt in Halifax at St Luke’s Cathedral and in the policy of the diocesan newspapers. Binney was in sympathy with Hodgson’s aims but he was always sensitive to those of the opposite persuasion and never identified himself publicly with either of the contending schools. But Binney’s Tractarian influence became so predominant that when the diocesan synod met in 1887 to select his successor, its first choice was the Reverend John Cox Edghill, a noted Tractarian and Anglo-Catholic.

Bishop Binney did not become closely involved in the political life of Nova Scotia. He did make comments which could be termed “political” on several occasions when decisions taken by government interfered with what he thought was the well-being of the Church of England. In the debate which surrounded the School Act of 1864 he stated that “no scheme of education which would omit religion from its plan, would be suitable.” Again at the beginning of the confederation debate he seemed to favour federalism when he appeared at a public rally with Thomas Louis Connolly*, Roman Catholic archbishop of Halifax. By 1870, however, he saw that the economic policies of the federal government would adversely affect Nova Scotia and the financial position of the church, and he informed the SPG of his fears that “confederation from which great benefits were expected by many is really doing us serious injury.” The difficulty he had in obtaining an act to incorporate the diocesan synod of Nova Scotia in 1863 indicates that his political influence was not very great, although he could count among his friends and family some of the most politically influential people in Nova Scotia. However, the day of a family compact was long gone, and the Anglican “party” was not nearly as powerful as the Roman Catholic and Presbyterian elements in Nova Scotia society.

When Binney came to the diocese in 1851 there were 36,482 Anglicans in Nova Scotia, comprising 10.3 per cent of the total population, who were served by 56 clergymen. When he died in 1887 the clergy had increased to 76, and in 1891 the Anglicans in Nova Scotia had risen to 64,410, making up 12 per cent of the total population. Binney left a permanent mark on the diocese. The diocesan synod with its episcopal veto still remains; the cathedral in Halifax came from his inspiration; above all, he raised the level of churchmanship in the diocese to the point where Anglicans began to feel a sense of responsibility for the support of their church.

Bishop Binney lived as one of the aristocrats of Halifax. Through his old and prominent family he inherited money, stocks, and property both in Nova Scotia and in England. He also inherited a great deal from his wife’s family. On 4 Jan. 1855 Binney had married Mary Bliss, the daughter of William Blowers Bliss*, senior puisne judge of the Superior Court of Nova Scotia, and member of one of the oldest and most distinguished loyalist families of Saint John, N.B. In 1854 Binney had purchased from James Boyle Uniacke* a Georgian stone mansion on Hollis Street, Halifax, next to Government House, and this spacious edifice saw many social functions. After his death in New York City in 1887, Binney’s estate was valued at between $400,000 and $500,000, most of which was left to his wife, three living children, and a granddaughter.

[There are almost no personal papers of Hibbert Binney available. The most valuable primary source for reconstructing his life’s work are the contemporary Halifax newspapers, particularly those of the Church of England. The papers of the Reverend George Wright Hodgson and Edward Jarvis Hodgson in St Peter’s Cathedral, Charlottetown, shed a good deal of light on Binney’s character. The only comprehensive research done on Binney is the following work: V. G. Kent, “‘The Right Reverend Hibbert Binney, colonial Tractarian, bishop of Nova Scotia, 1851–1887” (ma thesis, Univ. of New Brunswick, Fredericton, 1969). v.g.k.]

Hibbert Binney was the author of A charge delivered to the clergy at the visitation held in the Cathedral Church of St. Luke, at Halifax, on the 3rd day of July, 1866(Halifax, 1866); A charge delivered to the clergy at the visitation held in the Cathedral Church of St. Luke, at Halifax, on the 6th day of July, 1870(Halifax, 1870); A charge delivered to the clergy at the visitation held in the Cathedral Church of St. Luke, at Halifax, on the 30th day of June, 1874 (Halifax, 1874); A charge delivered to the clergy at the visitation held in the Cathedral Church of St. Luke, at Halifax, on the 6th day of July, 1880 (Halifax, 1880); A charge delivered to the clergy at the visitation held in the Cathedral Church of St. Luke, at Halifax, on the 1st day of July, 1884(Halifax, 1884); A charge delivered to the clergy at the visitation held in the Cathedral Church of St. Paul, at Halifax, on the 20th day of October, 1858(Halifax, 1859); A charge delivered to the clergy of the diocese of Nova Scotia, at the visitation held inthe Cathedral Church of St. Paul, at Halifax, on the 11thday of October, 1854 (Halifax, 1854); Observations upon the mission held in the city of Halifax, November 11th to November 22nd, 1883, addressed to the clergy of his diocese, by Hibbert, bishop of Nova Scotia (Halifax, 1883); A pastoral letter, including a correspondence between the Rev. Geo. W. Hill and himself, by Hibbert, lord bishop of Nova Scotia (Halifax, 1866); and Remarks on diocesan synods, addressed to the clergy and laity of his diocese (Halifax, 1864). The Correspondence between the bishop of Nova Scotia and the Reverend Canon Cochran, M.A., touching the dismissal of the latter from the pastoral charge of Salem Chapel, Halifax, N.S. (Halifax, 1866) was also published.

Halifax County Court of Probate (Halifax), no.1555, will of Hibbert Binney, 3 July 1868; no.2121, will of William Blowers Bliss, 7 Nov. 1873. St Peter’s Cathedral (Charlottetown), G. W. Hodgson papers; Service book, 13 June 1869. Univ. of King’s College Arch. (Halifax), Minutes of the Board of Governors, 1851–87. Church of England, Church Soc. of the Diocese of N.S., Report (Halifax), 1850–57; Diocese of N.S., Synod, Journal (Halifax), 1864, 1866, 1868, 1870–71, 1873. Proceedings and discussions connected with the introduction of a bill into the legislature of this province, by Bishop Binney, for the establishment of a Church of England synod in the diocese of Nova Scotia, and other papers relating thereto, ed. W. T. Townshend (Halifax, 1864), 6, 9, 93–94. Univ. of King’s College, Board of Governors, Investigation of the recent charges brought by Prof. Sumichrast against King’s College, Windsor, with letters, reports, and evidence (Halifax, 1872). Church Record (Halifax), 13 Oct. 1860, 12 June 1861, 27 Oct. 1864. Church Times (Halifax), 20 Dec. 1850; 3, 31 Jan., 18 April, 9 May 1851; 16, 30 April 1853; 26 Aug., 16, 23 Sept., 19 Oct. 1854; 19 May, 13 Oct. 1855; 18 Oct. 1856; 12 Nov. 1863. Halifax Catholic, 13 May 1854. Halifax Herald, 2 May 1887. Saint John Globe, 13 June 1887. Belcher’s farmer’s almanack, 1864. H. L. Clarke, Constitutional church government in the dominions beyond the seas and in other parts of the Anglican communion (London and Toronto, 1924). A. W. H. Eaton, The Church of England in Nova Scotia and the Tory clergy of the revolution (New York, 1891), 238–39. H. Y. Hind, The University of King’s College, Windsor, Nova Scotia, 1790–1890 (New York, 1890), 95. J. W. Lawrence, Foot prints; or, incidents in early history of New Brunswick, 1783–1883 (Saint John, N.B., 1883), 27. C. H. Mockridge, The bishops of the Church of England in Canada and Newfoundland . . . (Toronto, 1896), 141–42. Two hundred and fifty years young: our diocesan story, 1710–1960 (Halifax, 1960). Judith Fingard, “Charles Inglis and his ‘primitive bishopric’ in Nova Scotia,” CHR, 49 (1968): 247–66. D. C. Moore, “The late Bishop Binney of Nova Scotia,” Canadian Church Magazine and Mission News (Hamilton, Ont.), 2 (1887): 283–86.

Cite This Article

V. Glen Kent, “BINNEY, HIBBERT,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 11, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed December 31, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/binney_hibbert_11E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/binney_hibbert_11E.html |

| Author of Article: | V. Glen Kent |

| Title of Article: | BINNEY, HIBBERT |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 11 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1982 |

| Year of revision: | 1982 |

| Access Date: | December 31, 2025 |