Source: Link

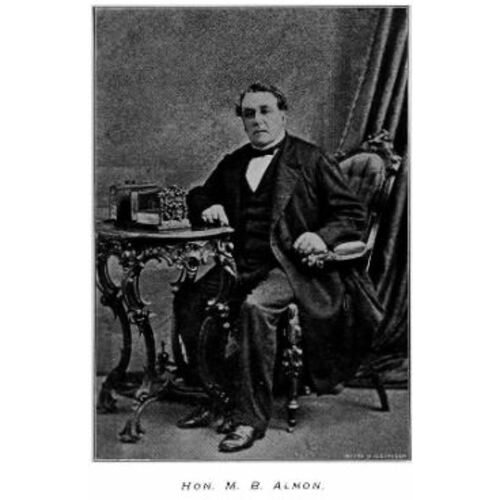

ALMON, MATHER BYLES, banker, politician, and philanthropist; b. at Halifax in 1796, son of William James Almon* and Rebecca Byles; d. at Halifax, 30 July 1871.

Mather Byles Almon was a member of a prominent Halifax family; his father was a loyalist and his mother was a daughter of Mather Byles Jr., a loyalist. Almon may have been educated privately for there is no record of his having attended the University of King’s College in Windsor, N.S., or of his having been educated abroad. On 31 Jan. 1825 he married Sophia, fourth daughter of John Pryor, a loyalist, a member of the assembly of Nova Scotia, and a merchant. Mather Byles and Sophia Almon had 14 children, of whom five died at a relatively early age.

The Almon family’s numerous social, political, and ecclesiastical connections undoubtedly aided Mather Byles Almon throughout his career. He set up his own general and wholesale firm in Halifax in the 1820s and continued to operate this business, which may have been financed by his family or with money from his wife, until he became active with the Bank of Nova Scotia. He was subsequently an insurance agent for the Halifax Fire Insurance Company and for the Halifax Marine Insurance Association, which he helped establish in 1838. He also acted as agent for several British firms including the Colonial Life Assurance Company, the Pelican Life Insurance Company, and the Phoenix Fire Insurance Company. In addition, he was associated with the Halifax Water Company and was particularly active, after 1836, with the Halifax Steamboat Company.

In 1832 Almon joined William Lawson*, William Blowers Bliss, Andrew Belcher, James William Johnston, James Boyle Uniacke*, and others to establish the Bank of Nova Scotia; Almon became a member of its first board of directors and in 1837 became its president. The bank established a branch in Windsor in 1832 and branches in Pictou, Yarmouth, Annapolis, and Liverpool in 1839. During this period the bank also made financial arrangements with the Baring Brothers in London and with the Merchant’s Bank of Boston, as well as with banks in New York, Portland, Maine, Saint John, N.B., and Montreal. This proved to be the limit of its expansion; during the depression of the early 1850s the bank closed its branches in Windsor, Annapolis, and Liverpool. One reason for its failure to grow was revealed by Almon on 28 July 1870 when he disclosed that James Forman, cashier of the bank since 1832, had embezzled $315,000 from the bank during a lengthy period of time. Evidence produced in a suit brought by the bank against Forman’s sureties indicated that Forman had carried out his defalcations since 1844. Almon, who was ill and virtually blind, had probably been unable to provide much leadership for some time. In September 1870 he resigned on the grounds that he was unable to sign the notes of the bank as required by law. It would seem obvious that he was incapable of handling any problems created by the loss of funds and any resulting loss of public confidence. The possibility exists that the bank might have been better served if he had resigned before 1870.

During his lifetime Almon built up an estate which, at his death, was evaluated at $616,000. Of this sum, $152,735 was invested in the United States, particularly in government bonds, and in insurance and banking stocks. He also held stock in several banks and public utilities in Newfoundland, Prince Edward Island, New Brunswick, and Quebec. Of the sum invested in his own province, $261,000 was in the form of mortgages and notes of hand. His chief investment in provincial manufacturing was through an American company which operated a coal mine in Pictou County and in a British firm, the Acadia Iron Company. The range of his investments indicates that he wanted an assured return which would provide protection against fluctuations in the provincial economy. His own reluctance to invest directly in provincial companies probably helps explain why the Bank of Nova Scotia did not become involved in the growth of the provincial economy in the mid-1850s.

In political life, Almon took some part in the administration of Halifax in the 1830s but withdrew from civic affairs after Halifax was incorporated in 1841. In October 1838 Almon, as a representative of the mercantile community, along with James B. Uniacke, James W. Johnston, and George Renny Young*, was appointed as a Nova Scotia delegate to meet Lord Durham [John George Lambton*] in Quebec. Charles Buller* thought this group to be “not only of striking ability, but of a degree of general information and polish of manners which are even less commonly met with in colonial society.” Almon became the centre of a political controversy in Nova Scotia in 1843 when Lieutenant Governor Falkland [Lucius Bentinck Cary*] named him to the Legislative and Executive Councils. He presented his mandamus as a member of the Legislative Council on 19 Feb. 1844. Lord Falkland told the colonial secretary, “I have admitted Mr. Mather B. Almon to the seat at the board which became vacant in February last [1843] by the retirement of Mr. [Thomas Andrew Strange] De Wolf”; thus Almon was probably a temporary member of the council in 1843 but it was not until after the election of 1843 that he was officially appointed. In December 1843 Joseph Howe and two supporters resigned their seats on the Executive Council accusing the governor and the Tory attorney general, J. W. Johnston, who was Almon’s brother-in-law, of weighting the council in favour of the Tories.

Almon and several other directors of the Bank of Nova Scotia played a prominent role in the Tory party. This political tie helped the bank, but it also gave the party a commercial tone. Almon, like other wealthy merchants of the day, probably gave financial contributions to the party. In 1864 Almon broke with the Conservatives and their new leader, Charles Tupper*, over the issue of confederation and became a prominent anti-confederate. In the critical year of 1866, however, failing health prevented his attending the Legislative Council. He remained a supporter of the anti-confederate provincial government until his death.

Almon was deeply interested in education, being a governor of Dalhousie University (1842–48) and a governor of King’s College (1854–68 and 1869–71). He became a member, and generous supporter, of almost every Protestant charitable society in Halifax; he was also a life member of several Church of England colonial missionary bodies. A great deal of his time, however, was devoted to St Paul’s Church. He was one of the faction which opposed the doctrinal changes proposed by Bishop Hibbert Binney*, who had been influenced by the Oxford movement. After several years of dissension, part of the congregation moved to St Luke’s in 1858, and the bishop followed in 1864. St Paul’s, which in the 1830s had been the dominant church in the province, retreated, under the leadership of men such as Almon, into respectable obscurity and parochialism. Thus, Almon’s religious beliefs, like his political ideas, failed to play a significant role in the changing community. Although he did help adapt Tory attitudes to a commercial, Victorian society, he was forced to watch as St Paul’s, the missionary societies, and the Legislative Council all lost their dynamic role in provincial affairs.

Bank of Nova Scotia Archives, Toronto, letter book, 1832–40; president’s memoranda and bank note issue book, 1856–71; Mather Byles Almon letters. PANS, Mather Byles Almon papers; “Senator William Johnson Almon and his descendants,” comp. by C. S. Stayner; “The Almons,” comp. by K. A. MacKenzie. Halifax County Court of Probate, will of M. B. Almon. Acadian Recorder (Halifax), 31 July 1871. Morning Chronicle (Halifax), 31 July 1871. Novascotian (Halifax), 1838, 1843–44. Harris, Church of Saint Paul, 206–9. History of the Bank of Nova Scotia, 1832–1900; together with copies of annual statements ([Toronto, 1900]), 45–51.

Cite This Article

K. G. Pryke, “ALMON, MATHER BYLES,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 10, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed April 25, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/almon_mather_byles_10E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/almon_mather_byles_10E.html |

| Author of Article: | K. G. Pryke |

| Title of Article: | ALMON, MATHER BYLES |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 10 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of revision: | 1972 |

| Access Date: | April 25, 2025 |