Source: Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

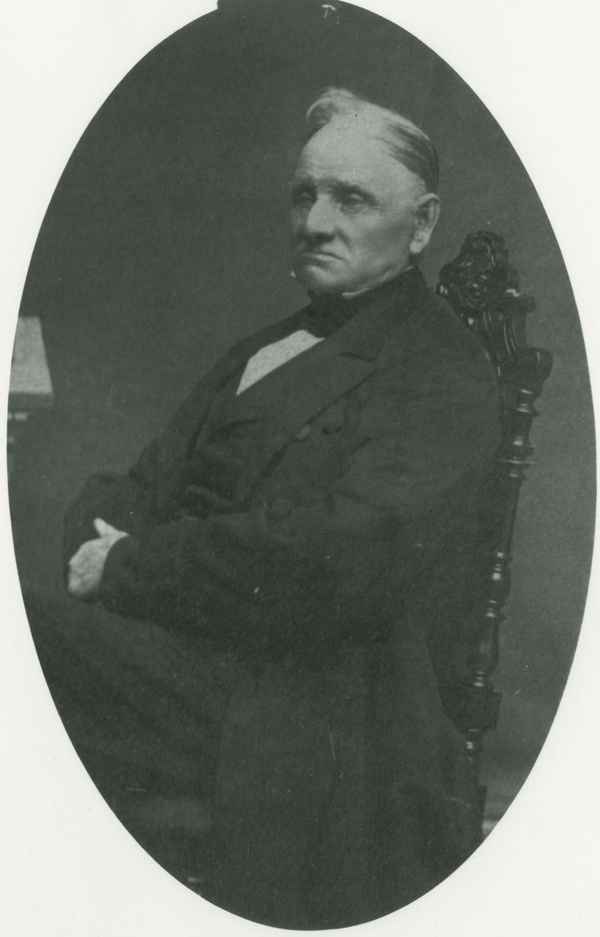

COLLINS, ENOS, seaman, merchant, financier, and legislator; b. at Liverpool, N.S., 5 Sept. 1774, first son of Hallet Collins and Rhoda Peek; d. at Halifax, N.S., 18 Nov. 1871.

Hallet Collins was a merchant, trader, and justice of the peace in Liverpool, N.S. He married three times, and was the father of 26 children; when he died in 1831 he left an estate of £13,000. His second child, Enos Collins, received little formal education, but went to sea at an early age probably as a cabin boy on one of his father’s trading or fishing vessels. Before he was 20, he was captain of the schooner Adamant, sailing to Bermuda; in 1799 he served as first lieutenant on the famed privateer Charles Mary Wentworth. An ambitious young man, Enos Collins soon obtained part-ownership in a number of vessels trading out of Liverpool. During the Peninsular War he made a large profit by sending three supply vessels to break the Spanish blockade and replenish the British army at Cadiz.

Soon Enos Collins’ ambitions outgrew the opportunities offered even by the thriving seaport of Liverpool, and he moved to Halifax where, by 1811, he was established as a merchant and shipper. During the War of 1812 he was an astute partner (with Joseph Allison) in a firm which bought captured American vessels from the prize courts and sold their cargoes at a profit. Probably the firm prospered too by illegally including New England in the war trade between Nova Scotia and the West Indies. Collins was part-owner of three privateers, including the Liverpool Packet, the most dreaded Nova Scotian vessel to ply New England waters during the war.

In the decade after the war Collins participated in numerous business enterprises. He was successful in currency speculation, backed many trading ventures, carried on his mercantile activities, and entered the lumbering and whaling businesses. Like most of his contemporaries, he invested in the United States; it was rumoured that his American investments equalled his holdings in Nova Scotia. By 1822 Collins’ ambitions seem once more to have outgrown his surroundings. Sir Colin Campbell* wrote to the colonial secretary, Lord Glenelg (Charles Grant), in 1838, “Sixteen years ago he [Collins] was about to remove from the Province for ever but was induced to remain by an offer made to him . . . of a seat in the council.”

Collins’ move into the principal governing body of the colony, the Council of Twelve, indicated the extent of his success. In 1825 he reinforced his position as a member of the ruling élite by marrying Margaret, eldest daughter of Brenton Halliburton*. In keeping with his social and economic position Enos Collins built a fine estate, Gorsebrook, where he and his wife entertained the governor and other leaders of the community. Collins and his wife had nine children, of whom one son and three daughters lived beyond childhood.

In 1825, after several unsuccessful attempts to gain a banking charter from the government, Enos Collins and a group of merchant associates – Henry H. Cogswell*, William Pryor*, James Tobin*, Samuel Cunard*, John Clark, Joseph Allison, and Martin Gay Black – formed a partnership and founded the Halifax Banking Company. The banking venture was the natural outgrowth of successful mercantile activity which provided each partner with the necessary capital to finance the new enterprise. Although Cogswell was president of the company, Collins was the dominant partner; the bank’s transactions were conducted in the building which housed Collins’ firm and the venture soon became known locally as “Collins’ Bank.”

One of the least attractive events of Enos Collins’ career concerns the brandy dispute of 1830. In 1826 the assembly had imposed a tax of 1s. 4d. on foreign brandy in addition to the 1s. imposed by the imperial government. The customs collector decided that a duty of 2s. was sufficient, but he failed to inform the assembly of his decision. In 1830 E. Collins and Company petitioned the assembly demanding a refund on their duty, arguing that the customs collector had given them an unfair rate of exchange on the doubloons with which they paid the tax. Their petition provided the assembly with the information that the full tax was not being collected. The assembly immediately passed a bill restoring the full tax, but the council, controlled by Enos Collins and his associates, refused to accept the bill. For some time no tax was collected on imported spirits, and Collins, taking full advantage of the situation, proceeded to sell his stocks of brandy without paying a penny into the treasury. His behaviour provoked an angry reaction in the assembly and from the local press. Unfortunately for Collins and the other importers, George IV died, causing an election in Nova Scotia. The brandy election of 1830, fought on the issue of the tax, resulted in the return of an assembly which quickly re-imposed the duty; the council accepted their decision. Not only did this dispute tarnish Collins’ name, but it also provided an issue around which criticism of the Council of Twelve could be concentrated.

During the 1830s Collins continued to expand his business activities and to participate in governing the colony. In 1832, despite Collins’ objections, the council granted a charter to the Bank of Nova Scotia and destroyed the monopoly of the Halifax Banking Company. Soon the two banks were involved in a currency battle which weakened the financial stability of the colony and gave Reformers another point of departure for attacks upon the ruling oligarchy. The decade witnessed growing discontent with the rule of the Council of Twelve, until, in 1837, the British government decided that reorganization was necessary. The new Executive Council of Nova Scotia did not originally include Enos Collins, but, at Governor Colin Campbell’s insistence, Collins became a member on 8 May 1838. He continued in the position until 6 Oct. 1840, when a second reorganization necessitated his resignation. During the turbulent 1840s and 1850s Collins refrained from active politics, but he was a financial backer of the Conservatives.

Enos Collins spent the last 30 years of his life in partial retirement keeping a close eye on his investments but withdrawn mainly to the privacy of Gorsebrook. The battle against confederation provided the last fighting ground for the old man. Breaking a lifetime allegiance with the Conservatives, Collins threw his whole-hearted financial support behind Joseph Howe, Mather Byles Almon, and other members of the anti-confederation league. The vehemence with which Collins opposed the scheme is best expressed by Howe: “Enos Collins who is now ninety years of age . . . declares that, if he was twenty years younger, he would take a rifle and resist it.”

Enos Collins was an astute, hard headed, and even progressive businessman. With an estate estimated at $6,000,000, he was rumoured to be the richest man in British North America. He belonged to the Church of England and supported it financially. Like his contemporaries, Collins recognized that the ruling class was responsible for the less fortunate and less successful members of society. He was a member of the Poor Man’s Friend Society and gave generously to the blind and to other philanthropic ventures which were common in 19th-century Halifax.

Collins’ life, however, does not represent a complete success story. He strove to become a member of the ruling oligarchy in a period when the changing times were giving political and social power to a much broader segment of the community. Long before Collins died, the way of life which he wanted and had achieved through his material success was disappearing. His stand against confederation was the last losing battle of a man who failed to recognize the vast changes occurring in British North America between 1840 and 1870.

PANS, “Collins family,” compiled by T. B. Smith; Log book of the privateer Charles Mary Wentworth. PRO, CO 217/115, 75–76. Acadian Recorder (Halifax), 8 Jan. 1898. Novascotian (Halifax), 1830, 1835–36, 1942. [Enos Collins], “Letters and papers of Hon. Enos Collins,” ed. C. B. Fergusson, PANS Bull., XIII (1959). J. F. More, The history of Queen’s County, N.S. (Halifax, 1873), 161–68. Ross and Trigge, History of the Canadian Bank of Commerce, I, 25–123. L. J. Burpee, “Joseph Howe and the anti-confederation league,” RSCT, 3rd ser., X (1917), sect.ii, 409–73. Peter Lynch, “Early reminiscences of Halifax – men who have passed from us,” N.S. Hist. Soc. Coll., XVI (1912), 171–204. G. E. E. Nichols, “Notes on Nova Scotian privateers,” N.S. Hist. Soc. Coll., XIII (1908), 111–52.

Cite This Article

Diane M. Barker and D. A. Sutherland, “COLLINS, ENOS,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 10, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed December 28, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/collins_enos_10E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/collins_enos_10E.html |

| Author of Article: | Diane M. Barker and D. A. Sutherland |

| Title of Article: | COLLINS, ENOS |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 10 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1972 |

| Year of revision: | 1972 |

| Access Date: | December 28, 2025 |