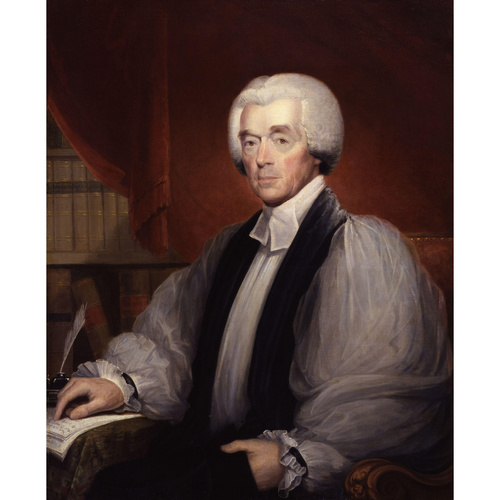

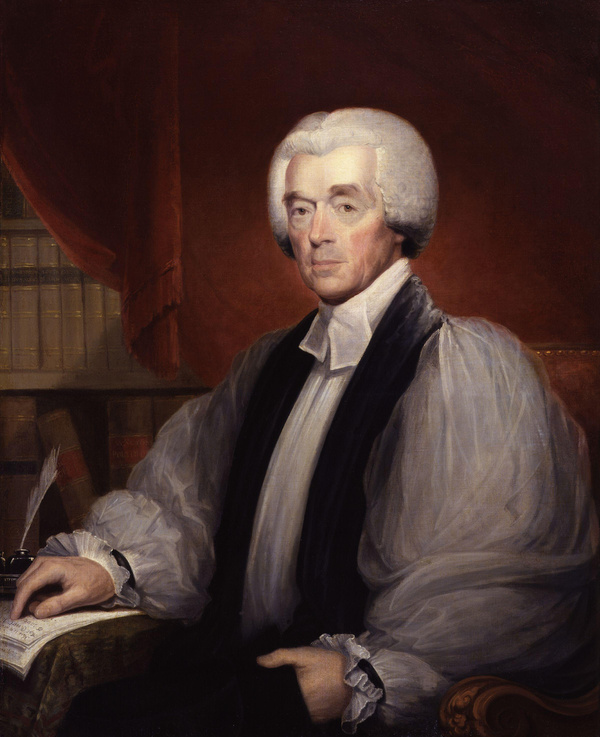

Source: Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

INGLIS, CHARLES, Church of England clergyman, bishop, and author; b. 1734 in Glencolumbkille (Republic of Ireland), third son of the Reverend Archibald Inglis; m. first February 1764 Mary Vining of Salem County, N.J.; m. secondly 31 May 1773 Margaret Crooke of Ulster County, N.Y., and they had four children; d. 24 Feb. 1816 in Aylesford, N.S.

Raised in a clerical family of Scottish descent, Charles Inglis was educated privately, his father’s early death depriving him of the opportunity to attend university. He emigrated to the American colonies before his 21st birthday, reputedly as a redemptioner, the means by which the poorer sort of emigrant in the 18th century commonly secured the expensive transatlantic passage. After he had taught for three years at a Church of England school in Lancaster, Pa, Inglis obtained the required testimonials to enable him to be admitted to holy orders in England. Ordained deacon and priest by the bishop of Rochester on 24 Dec. 1758, the young cleric returned to America as missionary to Dover, Del., where he served for six years. Early in 1766 he left the employment of the Society for the Propagation of the Gospel to accept appointment as one of the curates at Trinity Church, New York, though, fortunately for his later career, he remained in close touch with the Anglican missionary society. In New York the aspiring curate became involved in the unsuccessful campaign for the creation of colonial bishoprics and promoted the cause of missionary work amongst the Iroquois, a cause that received a considerable boost when John Stuart was appointed SPG missionary at Fort Hunter. He also furthered his deficient classical education by taking advantage of the cultural opportunities which an urban centre provided.

During the years of deteriorating relations between Britain and the Thirteen Colonies, Inglis, like many of his loyalist contemporaries, came to the conclusion that excessive colonial liberty was the root cause of Anglo-American problems. He also began to feel that the weakness of the colonial church, which was surrounded on all sides by disloyal dissenters, was the direct result of the imperial government’s failure to model American society on its English counterpart. His tory views, articulated in such discourses as the Letters of Papinian and The true interest of America impartially stated, exposed him to patriot hostility until the British occupation of New York in September 1776. That turn of events, combined with his succession to the rectorship of Trinity Church after the death of Samuel Auchmuty in 1777, won for him influence, safety, and a number of lucrative military chaplaincies behind military lines.

For Inglis, the end of the war coincided with tragic personal events: the death of his elder son and of his second wife. At the same time, the evacuation of New York in November 1783 forced him to resign his rectorship and return to England, where he spent the next three years jockeying with fellow refugees for pensions and preferments. Although he was unable to find the comfortable living in the United Kingdom for which he yearned, he did secure, with the patronage of Lord Dorchester [Guy Carleton], appointment in 1787 as first bishop of Nova Scotia, a position he held until his death. His diocese included not only the colony of Nova Scotia but also Newfoundland, St John’s (Prince Edward) Island, the old province of Quebec, and Bermuda. In 1793 this vast sphere of jurisdiction was narrowed with the appointment of Jacob Mountain* as bishop of the new see of Quebec, a diocese that embraced both Upper and Lower Canada.

Inglis entered upon his new duties amidst considerable opposition from the local clergy. Not only were they unused to hierarchical interference, but they were also angry that they had been denied a voice in the selection of their bishop. Furthermore, they were antagonistic towards Inglis because of his lack of formal education and his wartime career in New York, a career that in their view smacked of personal opportunism. Inglis also found Lieutenant Governor John Parr*, who was jealous of his gubernatorial authority, reluctant to share the local leadership of the established church. Even the SPG, long accustomed to exercising a remote but decisive influence over church administration at the mission level, initially became involved in jurisdictional clashes with Inglis. Eventually Inglis’s patience, tact, and appeals to the archbishop of Canterbury resolved his differences with the SPG; Parr’s death in 1791 removed another source of friction, and the appointment of an amenable fellow loyalist, John Wentworth, heralded a more harmonious era which Inglis’s erastian outlook helped to maintain.

In the case of the clergy, Inglis knew that the loyalists among them (comprising with their clerical sons one-half of the clergy in the Maritime portion of his diocese during the course of his episcopate) would prove difficult to manage. Many of them had been raised as dissenters in New England, their attitudes shaped as much by colonial traditions as by loyalist politics. For this reason they could rejoice in the creation of a colonial episcopate at the same time as they applauded its strictly circumscribed nature. It suited them well that the bishop had no patronage with respect to livings, no financial control over stipends, no cathedral, dean, and chapter to support his dignity, and no temporal powers or jurisdiction over the laity. Inglis, for his part, had neither the desire nor the authority to treat his clergy as subordinates. He was, however, determined to command at least token respect. One of the methods he employed was an essential component of English diocesan supervision: the triennial visitation. Conducted as plenary sessions, these visitations were initially resented by some of the missionaries, but Inglis countered their opposition by making attendance at the meetings compulsory. He was relatively successful in the results and continued to hold regular but separate visitations for the clergy of Nova Scotia and New Brunswick until his health deteriorated in 1812.

Yet, if Inglis was determined to uphold his episcopal authority, he also attempted to maintain harmonious relations with his clergy. To this end, he used the triennial visitations to consult with the clergy, not to dictate to them; his approach at these meetings mirrored a desire to follow a course of brotherly love and to appear as no more pre-eminent than a first among equals. He also pursued a policy of minimal interference in the day-to-day affairs of individual churches. On only one occasion did he take severe disciplinary action against a member of his clergy. In 1790 he was forced to dismiss the Reverend John Eagleson* of Cumberland County for drunkenness and incompetence. Astutely, he conducted the inquiry with the assistance of two of his clergy, Thomas Shreve and William Twining, a procedure that produced the appearance of a concerted decision by the church’s spiritual leaders. Inglis subsequently claimed that this episcopal act was his “most painful undertaking,” and he never again resorted to such an extreme course despite the misconduct and ineffectiveness of several of his clergy.

Inglis’s unwillingness to exert close personal supervision over the affairs of his diocese had the advantage of winning the support of independent-minded clergymen. Yet one aspect of his policy of non-interference – the infrequency of his confirmation tours – proved extremely damaging to the Anglican cause. It is debatable whether this failure to visit the diocese’s churches was a deliberate strategy designed to further amicable relations, or rather a convenient shunning of a responsibility that was made doubly tiresome by primitive conditions of travel. Whatever the case, Inglis managed only one trip to St John’s Island, in 1789 on his way to the Canadian portion of his diocese. Disputes in Sydney between the Reverend Ranna Cossit and the civil authorities forced Inglis to travel to Cape Breton in 1805, but he never troubled to visit Guysborough or Yarmouth at the opposite ends of the Nova Scotia peninsula, let alone tour distant Newfoundland. His other official tours were few, hardly an effective approach for one who saw himself essentially as a pioneer in church affairs. Nor did his sedentary habits provide much of an inspiration to a numerically weak denomination.

Although Inglis showed little interest in the concerns of individual churches, he did have a plan for the development of the church as a whole. One of his chief aims was to persuade the British and local governments to increase their financial assistance to the established church. As it turned out, he was forced to rely on the British government for most of the church’s funds, since local congregations and the colonial legislatures were reluctant to assume a greater share of financial responsibility. Nevertheless, he obtained enough financial aid from parliament, the SPG, and the colonial government to raise clerical stipends and to build or complete the modest wooden churches of the diocese.

Another part of Inglis’s plan was to provide the church with a larger corps of clergymen, and he therefore devoted himself to nurturing an educational institution for the benefit of the Anglican élite. Aware that the church’s future welfare depended on a stronger framework at the parish level, Inglis believed the primary aim of his college should be to produce well-trained native clergy. But the composition of the statutes of King’s College, opened at Windsor as a grammar school in 1788 and chartered as a university in 1802, was entrusted in 1803 not just to the bishop but to two of the church’s secular leaders, Alexander Croke* and Sampson Salter Blowers*, mere pettifogging lawyers, Inglis thought, who were out to vitiate his plans for a clerical seminary. Inglis strongly supported a statute requiring all applicants to the new institution to subscribe to the Anglican articles of religion, but he feared that other statutes did not go far enough towards consigning the care of the college to the bishop and ensuring the predominance of clergymen on the staff. A few years later, in 1806, he eagerly embraced the change made by the archbishop of Canterbury whereby non-Anglican matriculants would be allowed to study at King’s but would be denied their degrees until they subscribed to the Thirty-Nine Articles. Thus from the first he promoted a college that was as contemptuous of dissenters as the Oxbridge model he naturally admired. There was no reason to expect any other policy from a tory churchman, politicized by the American revolution, confirmed in his predilections by the French revolution, and dedicated to the concept of an established church.

Inglis had withdrawn into semi-retirement in 1795, moving from the provincial capital of Halifax to Windsor, and the following year he settled on his country estate near Aylesford. One critic of this move suggested that Inglis feared a French attack; Inglis himself claimed that the sea air adversely affected his health and that the valley was a more central location for his diocesan residence. As a gentleman farmer he pursued an enthusiasm for agriculture, his lands being admired for their fine orchards and progressive tenantry. During his Aylesford years effective control of the bishopric passed from the reticent, unambitious father to the precocious, aggressive son, John*, whom Inglis groomed as his successor and appointed his secretary and ecclesiastical commissary for Nova Scotia in 1802. It was largely out of concern for the future career of his son that Inglis was attracted back to Halifax in 1808 by an increase in salary and appointment to the Council. Subsequently, he participated only sporadically in the affairs of state until he suffered a stroke in 1812 which left him largely incapacitated for the last few years of his life. Although he failed to secure the immediate episcopal succession for his son, he left him a wealthy man. His bequests to John and two daughters included the Aylesford estate and over 12,000 acres of land in the Annapolis valley.

A bewigged prelate, slender of build and dapper in attire, Inglis enjoyed books and rural pastimes, particularly when surrounded by his small but closely knit family. This leisurely style of life reflected his reluctance to become involved in local political squabbles which paled into insignificance when compared either with the heady ferment of the American revolution or with the momentous events on the continent of Europe. The years of his episcopacy formed an anti-climax to a controversial career. His failure to become more active in the concerns of both church and community may have been extremely judicious in the circumstances, but it also reflected his satisfaction at drawing a handsome salary in return for minimal exertion and as a reward for past rather than present services to the British empire.

Inglis’s character and career have been distorted by hagiography. Much of the historical praise is based on his distinction as the first colonial bishop of the Church of England, a landmark, admittedly, but hardly an adequate ground on which to assess his reputation. The other enthusiasms of Inglis’s posthumous partisans have been more fundamentally misleading. Most damaging to historical inquiry has been their refusal to recognize that the bishop’s views on education were as illiberal as those of the staunchest churchmen in his diocese. Another of their failings has been their uncritical interpretation of Inglis’s record as bishop. In picturing him as an energetic, hard-working administrator, Inglis’s champions have missed the underlying personal objective of his episcopate: a tranquil, comfortable retirement to compensate for his steadfast loyalty. By the same token they have misinterpreted his approach to official duties. Far from displaying the energy and zeal with which he has been credited, he studied to be quiet, to maintain a discreet presence, and to confine himself as much as possible to the less controversial concerns of his denomination. True, it was as a result of his moderate churchmanship and guarded approach that the Church of England emerged from these years without deep divisions. But Inglis’s additional success in maintaining relatively good relations between the Church of England and rival denominations should not be attributed to any astute appreciation on his part of the inescapable realities of religious pluralism. It should rather be seen as a reflection of the fact that at this early stage in the social development of Nova Scotia, the leaders of non-Anglican churches were not as sophisticated, articulate, and sensitive to the inequities of church establishment as they were shortly to become.

[Charles Inglis’s publications include The true interest of America impartially stated, in certain stictures on a pamphlet intitled “Common sense”; by an American (Philadelphia, 1776); The letters of Papinian: in which the conduct, present state and prospects, of the American Congress are examined (New York, 1779); Remarks on a late pamphlet entitled “A vindication of Governor Parr and his Council” . . . by a consistent loyalist (London, 1784); Dr. Inglis’s defence of his character, against certain false and malicious charges contained in a pamphlet, intitled, “A reply to remarks on a vindication of Gov. Parr and his Council” . . . (London, 1784); A sermon preached before his excellency the lieutenant governor, his majesty’s Council, and the House of Assembly, of the province of Nova-Scotia, in St. Paul’s Church at Halifax, on Sunday, November 25, 1787 (Halifax, 1787); A charge delivered to the clergy of the diocese of Nova Scotia, at the primary visitation holden in the town of Halifax, in the month of June 1788 (Halifax, 1789); A charge delivered to the clergy of the province of Quebec, at the primary visitation holden in the city of Quebec, in the month of August 1789 (Halifax, [1789]); A charge delivered to the clergy of Nova Scotia, at the triennial visitation holden in the town of Halifax, in the month of June 1791 (Halifax, [1792]); Steadfastness in religion and loyalty; recommended, in a sermon preached before the legislature of his majesty’s province of Nova-Scotia; in the parish church of St. Paul, at Halifax, on Sunday, April 7, 1793 (Halifax, 1793); A sermon preached in the parish church of St. Paul at Halifax, on Friday, April 25, 1794: being the day appointed by proclamation for a general fast and humiliation in his majesty’s province of Nova-Scotia (Halifax, 1794); The claim and answer with the subsequent proceedings, in the case of the Right Reverend Charles Inglis, against the United States; under the sixth article of the treaty of amity, commerce and navigation, between his Britannic majesty and the United States of America (Philadelphia, 1799); A sermon on confirmation: preached in St. John’s Church, Cornwallis, on Sunday, September 13, 1801 (Halifax, 1801); and A charge delivered to the clergy of the diocese of Nova-Scotia, at the triennial visitation holden in the months of June and August, 1803 (Halifax, 1804).

Several of his letters were published in “The first bishop of Nova Scotia: chap.IV, the first colonial episcopate,” ed. W. S. Perry, Church Rev. (New Haven, Conn.), 50 (July–December 1887): 343–60. His papers, and those of his son John, remain in the hands of his descendants. Microfilm and transcript copies are available in PANS, MG 1, 479–82 (transcripts); Biog., Charles Inglis, letters, journals, and letterbooks (mfm.); and John Inglis, letters (mfm.). j.f.]

Halifax County Court of Probate (Halifax), I1 (will and estate papers of Charles Inglis) (mfm. at PANS). Lambeth Palace Library (London), Manners-Sutton papers; Moore papers; SPG papers, X: 189–92, 232; XI: 37–41, 45–48, 53–55, 57–58, 68–70, 77–111. PRO, CO 217/56–98. Protestant Episcopal Church in the U.S.A., Arch. and Hist. Coll. – Episcopal Church (Austin, Tex.), Samuel Peters papers, in the custody of the Hist. Soc. of the Episcopal Church (Austin). QDA, 72 (C-1), docs.9, 16, 21, 77; 75 (C-4), docs.76, 91. Univ. of King’s College Library (Halifax), Univ. of King’s College, Board of Governors, letterbook of the secretary, 1803–18; minutes and proc., 1 (1787–1814), 2 (1815–35); corr. relating to King’s College, 1789–1889; statutes, rules, and ordinances of the University of King’s College at Windsor in the province of Nova Scotia, 1803, 1807. USPG, Journal of SPG, 23–31; B, 2; X, 142–48. T. B. Akins, A brief account of the origin, endowment and progress of the University of King’s College, Windsor, Nova Scotia (Halifax, 1865). [John Inglis], Memoranda respecting King’s College, at Windsor, in Nova Scotia; by one of the alumni (Halifax, 1836). DAB. Carl Bridenbaugh, Mitre and sceptre: transatlantic faith, ideas, personalities, and politics, 1689–1775 (New York, 1962). Susan Buggey, “Churchmen and dissenters: religious toleration in Nova Scotia, 1758–1835” (ma thesis, Dalhousie Univ., Halifax, 1981). R. M. Calhoon, The loyalists in revolutionary America, 1760–1781 (New York, 1973). Philip Carrington, The Anglican Church in Canada; a history (Toronto, 1963). S. D. Clark, Church and sect in Canada (Toronto, 1948). Hans Cnattingius, Bishops and societies: a study of Anglican colonial and missionary expansion, 1698–1850 (London, 1952). A. L. Cross, The Anglican episcopate and the American colonies (New York, 1902). A. W. [H.] Eaton, The Church of England in Nova Scotia and the tory clergy of the revolution (New York, 1891). Judith Fingard, Anglican design in loyalist N.S.; “The Church of England in British North America, 1787–1825” (phd thesis, Univ. of London, 1970). V. T. Harlow, The founding of the second British empire, 1763–1793 (2v., London and New York, 1964), 2: 735–42. R. V. Harris, Charles Inglis: missionary, loyalist, bishop (1734–1816) (Toronto, 1937). H. Y. Hind, The University of King’s College, Windsor, Nova Scotia, 1790–1890 (New York, 1890). G. H. Lee, An historical sketch of the first fifty years of the Church of England in the province of New Brunswick (1783–1833) (Saint John, N.B., 1880). J. W. Lydekker, The life and letters of Charles Inglis: his ministry in America and consecration as first colonial bishop, from 1759 to 1787 (London and New York, 1936). W. H. Nelson, The American tory (Oxford, 1961). M. B. Norton, The British-Americans: the loyalist exiles in England, 1774–1789 (Boston and Toronto, 1972). W. S. Perry, A missionary apostle; a sermon preached in Westminster Abbey, Friday, August 12, 1887, on the occasion of the centenary of the consecration of Charles Inglis, first bishop of Nova Scotia . . . (London, 1887). H. C. Stuart, The Church of England in Canada, 1759–1793, from the conquest to the establishment of the see of Quebec (Montreal, 1893). J. [E.] Tulloch, “Conservative opinion in Nova Scotia during an age of revolution, 1789–1815” (ma thesis, Dalhousie Univ., 1972). C. W. Vernon, Bicentenary sketches and early days of the church of Nova Scotia (Halifax, 1910); The old church in the new dominion; the story of the Anglican church in Canada (London, [1929]). [F. W.] Vroom, “Charles Inglis,” Leaders of the Canadian church, ed. W. B. Heeney (3 ser., Toronto, 1918–43), ser.1: 1–33; King’s College: a chronicle, 1789–1939; collections and recollections ([Halifax, 1941]). J. M. Bumsted, “Church and state in maritime Canada, 1749–1807,” CHA Hist. papers, 1967: 41–58. Judith Fingard, “Charles Inglis and his ‘Primitive Bishoprick’ in Nova Scotia,” CHR, 49 (1968): 247–66. R. S. Rayson, “Charles Inglis, a chapter in beginnings,” Queen’s Quarterly (Kingston, Ont.), 33 (1925–26): 163–77. C. M. Serson, “Charles Inglis, first bishop of Nova Scotia,” American Church Monthly (New York), 42 (1937–38): 215–28, 264–78. F. W. Vroom, “Charles Inglis: an appreciation,” N.S. Hist. Soc., Coll., 22 (1933): 25–42. S. F. Wise, “Sermon literature and Canadian intellectual history,” United Church of Canada, Committee on Arch., Bull. (Toronto), 18 (1965): 3–18.

Cite This Article

Judith Fingard, “INGLIS, CHARLES,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 5, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed December 13, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/inglis_charles_5E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/inglis_charles_5E.html |

| Author of Article: | Judith Fingard |

| Title of Article: | INGLIS, CHARLES |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 5 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1983 |

| Year of revision: | 1983 |

| Access Date: | December 13, 2025 |