Source: Link

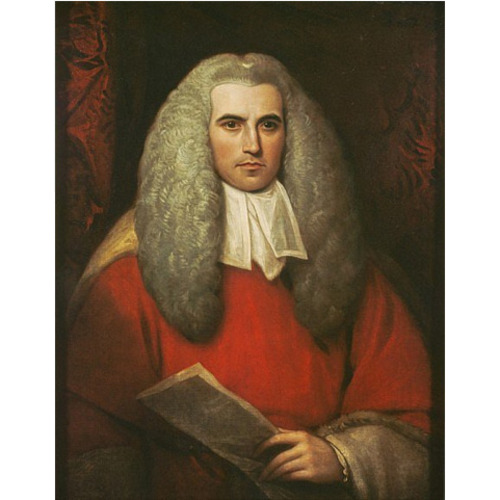

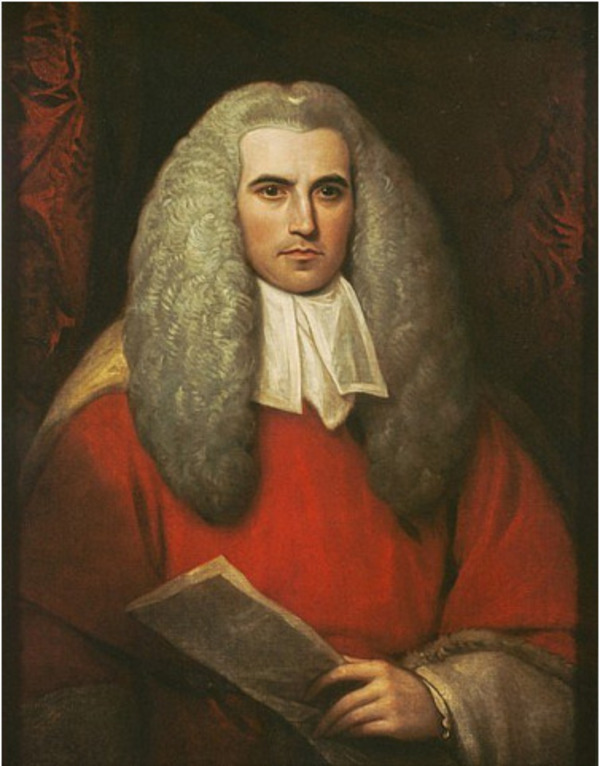

STRANGE, Sir THOMAS ANDREW LUMISDEN, judge; b. 30 Nov. 1756 in England, probably in London, second son of Robert Strange, a prominent engraver, and Isabella Lumisden; brother of James Charles Stuart; m. first 28 Sept. 1797 Jane Anstruther in London; m. secondly 11 Oct. 1806 Louisa Burroughs, and they had a large family; d. 16 July 1841 in St Leonards (East Sussex), England.

Thomas Andrew Lumisden Strange entered Westminster School, London, in 1769 and Christ Church College at Oxford in 1774, graduating from the latter institution with a ba (1778) and an ma (1782). Admitted to Lincoln’s Inn in 1776, he was called to the bar in November 1785 and four years later was appointed chief justice of Nova Scotia. Strange’s appointment might be explained by his mother’s friendship with Lord Mansfield, a former cabinet minister. The nomination came during a dispute between the Nova Scotia House of Assembly and the Council, in part involving charges of partiality against justices James Brenton* and Isaac Deschamps* of the Supreme Court who had presided in the absence of a chief justice.

Strange’s main task on his arrival at Halifax in May 1790 was to conciliate the warring factions, which he found anxiously watching him. To that end he dined “with every one who invited me,” including Jonathan Sterns, a lawyer whose suspension by Deschamps had been an early event in the so-called judges’ affair. Strange reinstated Sterns and managed to establish friendly relations with Brenton and Deschamps, whom he found “very amiable, deserving persons and of great assistance to me.” His tact, the passage of time, and the diversion created by the war with France in 1793 resolved the crisis.

For the most part, Strange’s judicial duties had little to do with the dispute between assembly and Council. Most Supreme Court cases in the 1790s concerned the recovery of debts, which were usually small sums, although one case in 1790 involved a debt of more than £24,000 Halifax currency. Occasionally, however, cases with political overtones reached the court. In 1793 Solicitor General Richard John Uniacke* accused Francis Green*, son of a former treasurer of the colony, of libel in connection with an attempt by Uniacke and others to obtain some papers from Green. Strange found Green guilty and awarded Uniacke £500 in damages

Although careful not to overlook his primary mission in Nova Scotia, Strange apparently also found time to use his influence as chief justice to oppose slavery. His successor, Sampson Salter Blowers, claimed that in cases involving runaway slaves Strange required “the fullest proof of the master’s claim” and that since this was difficult to produce “it was found generally very easy to succeed in favour of the Negro.” Blowers, as attorney general, and Strange frequently discussed how to proceed in such matters, and Strange decided to move slowly rather than “throw so much property as it is called into the air at once.”

From the beginning many people in the colony liked Strange. Governor John Parr* expressed regret that Strange had not arrived earlier, and declared that the chief justice could have saved him much trouble and anxiety. Parr’s successor, John Wentworth*, expressed satisfaction with Strange on numerous occasions. In 1793, for example, Wentworth reported that sessions of the Supreme Court had not been held in several counties that year, but said it was “notwithstanding the best diligence of our good Ch. Justice, who is indefatigable in his duty.” When in 1794 Wentworth realized that Strange might be attracted to a post in another colony, he declared that it would be “the greatest misfortune to this province and to myself.”

Bishop Charles Inglis* also spoke highly of Strange for his abilities as chief justice, his “life of strict probity & virtue,” and his contribution as a member of the board of governors to the development of King’s College. Strange apparently showed a much greater interest in the college than did some of his fellow governors. He visited it on several occasions, worked with Inglis on plans for new buildings, and gave £100 towards a college library. He was far more concerned by the possible cost of the college than Inglis was, but he hoped that it would become “the Centre of Learning to the King’s Transatlantic Dominions.”

Despite his evident popularity, Strange became unhappy in Nova Scotia. In 1794 he expressed dissatisfaction with Wentworth and “the Habits of his Family,” an apparent reference at least in part to Wentworth’s morals. He also alleged that Wentworth had not been open with him “in his views of Government.” That year Strange sought the chief justiceship of Upper Canada, and expressed a desire to embrace “the first opportunity of quitting this place.” In some measure, Strange wanted a move for financial reasons. His salary was to have been £1,000, with £200 to come from fees. But he discovered that the fees “consisted of small sums, to be received often from very indigent people, who could but ill afford to pay them,” and he had found deriving any of his income from such a source disagreeable. From time to time Strange gave some of the £200 fee money for a law library, and then contributed to a collection of books “of a more popular Nature” for the town.

In 1795 Strange stopped seeking the appointment in Upper Canada and instead requested permission to tour the United States when the war with France ended. His desire to get away may have been strengthened by his feelings of loss after his close friend the Reverend Andrew Brown* departed for Scotland that year. On 25 July 1796 Strange himself left for England. Although he indicated that he was only going home for a visit, as he had in 1791, he was apparently not believed. In 1797 he informed Wentworth of his intention to resign. A year later he went to Madras (India) as recorder and president of its court. He was knighted on 14 March 1798, before his departure. In 1800 he became chief justice of the Madras supreme court, over which he presided until his return to England in 1817. He also wrote Elements of Hindu law (2v., London, 1825), for many years the definitive work on the subject.

As chief justice in Nova Scotia, Strange’s achievement in keeping the peace and winning respect for the Supreme Court was no mean feat. Blowers’s observation that Strange was “a most excellent theoretical lawyer,” but had practised little and once made an error in a trespass case which he had had to point out, seems petty in view of the praise Strange received from many quarters.

PANS, MG 1, 480 (transcripts), 1595–613; RG 39, HX, C, 1790 (A–K), 1792 (S–Z), 1793 (A–Z), 1794 (A–H). PRO, CO 217/36–37, 217/62–67 (mfm. at PANS). Royal Gazette and the Nova-Scotia Advertiser, 1790. DNB. Cuthbertson, Old attorney general. R. W. Winks, The blacks in Canada: a history (London and New Haven, Conn., 1971). Margaret Ells, “Nova Scotian ‘Sparks of Liberty,’ Dalhousie Rev., 16 (1936–37): 475–92. J. E. A. Macleod, “A forgotten chief justice of Nova Scotia,” Dalhousie Rev., 1 (1921–22): 308–13. T. W. Smith, “The slave in Canada,” N.S. Hist. Soc., Coll., 10 (1896–98): 1–161.

Cite This Article

Donald F. Chard, “STRANGE, Sir THOMAS ANDREW LUMISDEN,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 7, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed December 12, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/strange_thomas_andrew_lumisden_7E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/strange_thomas_andrew_lumisden_7E.html |

| Author of Article: | Donald F. Chard |

| Title of Article: | STRANGE, Sir THOMAS ANDREW LUMISDEN |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 7 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1988 |

| Year of revision: | 1988 |

| Access Date: | December 12, 2025 |