Source: Link

NAME UNRECORDED, enslaved Black youth, b. c. 1772 in an American colony; d. likely after 1786.

An enslaved male

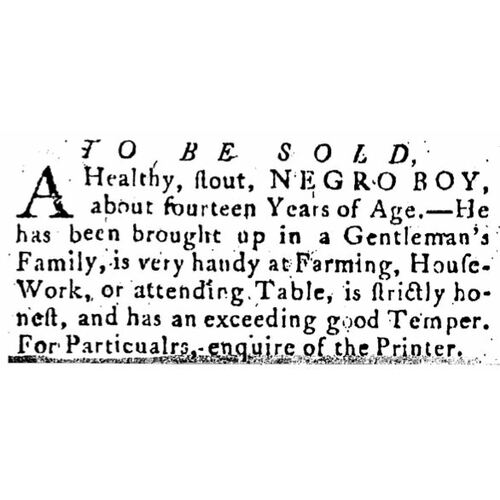

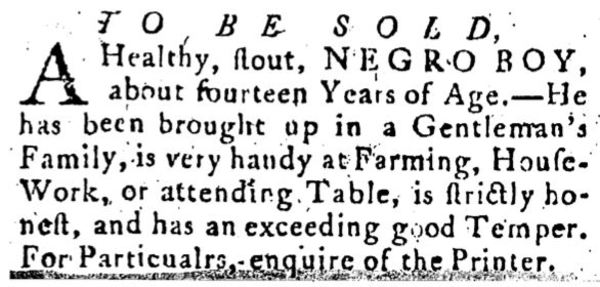

A slave owner in Shelburne, N.S., placed an advertisement in the June 1786 issue of the Royal American Gazette [see James Robertson*] listing an enslaved Black youth for sale. It described a “healthy, stout, negro boy, about fourteen Years of Age” who had “been brought up in a Gentleman’s Family, is very handy at Farming, House-Work, or attending Table, is strictly honest, and has an exceeding good Temper.” Nothing else is known about him – not his name, his background, his family – or about those who regarded him as their property.

Black people were enslaved throughout the Atlantic world, including in Shelburne, a loyalist settlement briefly known as Port Roseway, which was founded in 1783. Surviving historical documents reveal little about specific experiences of the enslaved. In many cases names were not recorded. In others, only a name survives – nothing else. Occasionally, a broader documentary record – an unusually detailed burial record, a naval officer’s diary entry, a legal brief, a deposition – sheds light on individual lives, as in the cases of Diana Bestian, Lydia Jackson, Nancy, Statia*, and Isaac Willoughby*. But these remain the exception. The names, lives, and stories of countless others are lost.

The Atlantic slave trade

Slavery in colonial Canada was part of the much broader Atlantic slave trade. The major European powers and several African kingdoms were enriched by this cruel commerce in human flesh, an economic system that grew exponentially in the 18th century. More than ten million people were brought to the Americas, the vast majority destined for Brazil. About 400,000 arrived in the American colonies, where slave owners exploited their labour to profit from staple crops such as sugar, tobacco, and rice. A minority of North American slaves ended up in the Maritimes.

By the 1770s most of those enslaved in the American colonies had been born there. The Chesapeake region, comprising Maryland and Virginia, developed a self-reproducing slave population, and New England and New York also had many native-born slaves. It is thus unlikely that the youth advertised for sale in 1786 was from Africa. If he were, his owner or owners may have brought him to New York and then to the Maritimes via the West Indies, an area that continued to see a more limited African trade.

Slavery in the Maritimes

The end of the American Revolutionary War resulted in an influx of white loyalists, their slaves, and free Black loyalists to the Maritimes. White loyalists greatly expanded slavery in the region, building upon existing systems in Île Royale (Cape Breton) [see Marguerite*] and among the New England planters.

The scope and nature of the region’s form of slavery is difficult to gauge because it is not always clear whether an individual was a slave or an indentured servant. The propensity of white loyalists to re-enslave free Black people and the failure of the colonial governments to conduct a slave census make it particularly difficult to estimate numbers. Even so, it is probable that at least 1,500 individuals (and possibly as many as 2,500), perhaps including this once-known young male, unwillingly accompanied their loyalist owners to the Maritimes. Some may have settled permanently, while others perhaps returned to the United States.

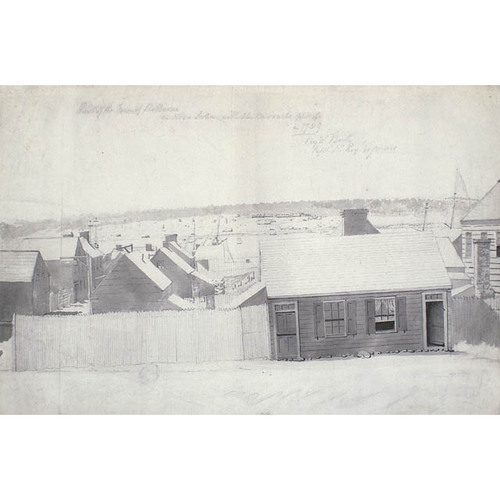

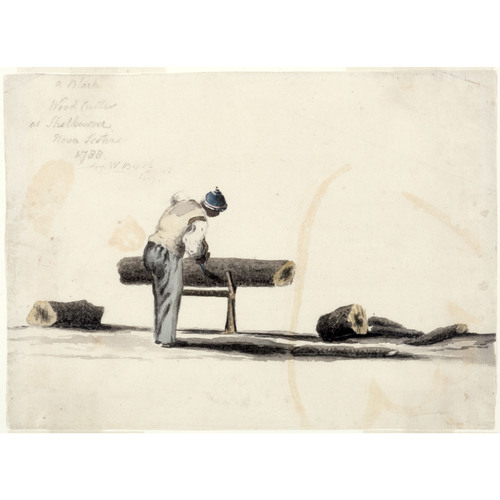

If brought to Shelburne from New England or New York, he would have found little difference in his circumstances in the Maritimes. Slavery across the North American northeast occurred in the context of small holdings, with typically only one to three enslaved people per household. Their labour would have included both farm and domestic work, and they would have had close relationships, however fractious, with their owners. A few loyalists, such as James Moody* and John Polhemus, kept more than eight slaves, but this was rare and still far below the numbers belonging to owners of plantations in the southern United States. In the Maritimes master and slave often worked side by side and were always in one another’s space, another significant difference from slavery in South Carolina or Virginia, where Black people rarely saw their owners or overseers.

Contesting slavery in colonial Canada

The intimacy of Maritime slave-to-owner relations did not stop the enslaved from establishing families, friendships, culture, or communities, even though they were a minority within the dominant white society. Despite this imbalance, rising opposition to slavery within the British empire meant that owners could not operate with impunity.

No slave laws existed in the Maritimes, except in St John’s Island (later Prince Edward Island, where a 1781 slave baptism law legalized the institution until its repeal in 1825), yet owners attempted several times to introduce them. Such efforts were frequently challenged by those who did not own slaves, as in Nova Scotia, where masters trying to add slavery to statute law under the guise of gradual emancipation legislation (comparable to that adopted by Upper Canada in 1793) were thwarted in 1787, 1789, 1801, and 1808; a similar effort in New Brunswick failed in 1801.

The legal fight to end slavery progressed unevenly across the Maritimes. Enslaved people tried to secure their freedom through the courts, and in Nova Scotia the chief justices Sampson Salter Blowers* and Sir Thomas Andrew Lumisden Strange* were among those who ruled against slavery. Both men avoided direct judgements, preferring to gradually strip white people of their human property. When the enslaved escaped, their owners usually attempted to recover them through the courts. But without an established legal right to own slaves, proving ownership was difficult; Blowers’s rulings, especially, made it nearly impossible to justify the legality of owning another human. Hard-line masters in Digby complained in an 1808 petition that the Nova Scotia courts had undermined slavery and allowed their slaves to treat them with “defiance.” Yet these petitioners seem to have eventually concluded that it was better to retain their slaves as freed servants and hire them for pay.

The New Brunswick courts ruled differently. Justices there were either evenly split on the issue or, as was the case in 1806, found in favour of enslavement. Yet the practice began to die out and slave advertisements became rarer, replaced by notices for servants. As had been determined in Nova Scotia, it made sense to retain individuals as servants for what were likely very low wages.

One of the last documented references to enslaved people in colonial Canada is an 1828 entry in a Montserrat slave register from the West Indies, six years before emancipation in most of the British empire. The recorder noted that a Mr Ormsby had three enslaved people living with him in Prince Edward Island – three years after it had repealed the legalization of slavery.

A slave in Shelburne

While the situation in the British colonies differed vastly by region and country (consider Nova Scotia, Virginia, and Jamaica), one constant was the commodification of Black people – as in the case of the male advertised for sale in 1786. His humanity came second to pecuniary interests, his name valueless to his master and, presumably, potential buyers.

Not knowing who offered him for sale, why, or whether he was even sold makes it challenging to trace his life. But the description of this “healthy, stout, negro boy” and the emphasis on his impressive range of skills – raised in a gentleman’s family, handy at farming and housework, honest, possessing a good temper – suggests that he would have appealed only to a well-off family in Shelburne, an increasingly small group by 1786. By this time, many of Shelburne’s wealthier inhabitants had returned to the United States with their slaves, and others would soon follow. It may be that this male was being sold because his owner planned to move there too and needed funds.

The economic prospects in the settlement were not good. Despite the rapid movement of loyalists to the area only three years earlier, by the mid 1780s Shelburne’s economy was in recession. Tensions erupted as early as 1784, when white people rioted against the free Black population for their willingness to labour for lower wages. The settlement would continue to decline over the coming decade.

If this young person ventured about at all during the years before he was advertised for sale, he would have seen that matters were even more dire for Shelburne’s Black population. Methodist preacher Boston King*, who came to the settlement after he could not find employment in nearby Birchtown despite being a carpenter, noted that poverty was so bad that some fell dead of hunger.

We can only speculate about whether this youth attended King’s services or those of David George*, another prominent Black preacher then ministering in Shelburne. Less speculative is the likelihood that he knew he lived in a settlement with a sizeable free Black community. What must he have thought about residing on the edge of freedom? Did he entertain the idea of escape? He certainly would have heard about owners threatening to sell enslaved people to buyers in the West Indies, which occurred regularly.

Questions abound – about his family, his hopes, his fears. His fate, like his identity, remains a mystery. What is clear is that his experience of enslavement, on the fringe of the British empire in Shelburne, was shaped by the broader context of North American slavery, the loyalist exodus from the new American republic, and the specific conditions in Shelburne during the 1780s – one page of the wider story of the Black Atlantic world.

Royal American Gazette (Shelburne, N.S.), 19 June 1786. Black slavery in the Maritimes: a history in documents, ed. H. A. Whitfield (Peterborough, Ont., 2018). H. A. Whitfield, Biographical dictionary of enslaved Black people in the Maritimes (Toronto, 2022); North to bondage: loyalist slavery in the Maritimes (Vancouver and Toronto, 2016).

Cite This Article

Harvey Amani Whitfield, “NAME UNRECORDED (fl. 1772–86),” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 4, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed April 10, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/name_unrecorded_4E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/name_unrecorded_4E.html |

| Author of Article: | Harvey Amani Whitfield |

| Title of Article: | NAME UNRECORDED (fl. 1772–86) |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 4 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of revision: | 2024 |

| Access Date: | April 10, 2025 |