Source: Link

NANCY (possibly also known as Ann), enslaved Black woman; b. c. 1762 in Maryland; d. after 1800.

Born in Maryland to an African mother who was herself enslaved, Nancy probably grew up in Somerset County on Maryland’s eastern shore. The area’s many small farms produced a variety of agricultural goods. Her owner, the irascible and mercurial Caleb Jones*, came from the lower middle ranks of society and held great ambitions to advance himself. In 1773 he improved his position by marrying Elizabeth (Betty) Wheatley, a daughter of the wealthy Major Sampson Wheatley, who had many slaves. It is likely that Jones came to own Nancy sometime after his marriage and before 1776, when he fled Maryland for New York, where he joined the Maryland Loyalists. According to his 1802 memorial, his property during the American Revolutionary War included some “ten or twelve slaves.”

Prior to the 1783 evacuation of New York City, Jones was given six months’ leave to scout land for loyalist settlement in New Brunswick. He decided to settle in the Fredericton area and was granted about 900 acres, including riverfront property, with good timber. He returned to New York in 1785 and purchased two slaves, whom he brought back to begin working his land. Knowing he needed more labourers, Jones travelled again to Maryland to bring Nancy and six of his other slaves to New Brunswick. A 1785 census of Maryland settlers indicates that Nancy, Isaac, and Ben were adults and the other four were children – Sarah, Harry, Tab (or Jab), and Elijah (Lidge). When Jones returned to New Brunswick, he discovered that the two slaves he had left behind had run off. He needed many hands to clear his substantial holdings; Nancy would have toiled on the land and probably as a domestic as well. In 1786, with work on his property under way, Jones headed south once more, this time to retrieve his wife and son.

It is significant that so many of Jones’s slaves ran away from him; he may well have been a hard-driving man who overworked his human property. That spring Ben escaped but was recaptured. In March Jones offered a five-dollar reward for this “negro man,” whom he described as about 30 years of age, “stout and well set” and wearing “a light brown jacket, a plaid waistcoat, corduroy breeches, white stockings, and a round hat.”

A few months after Ben had fled, Nancy and three others also escaped, but were retaken. In advertising for their return, Jones informed readers of the Royal Gazette and New Brunswick Advertiser (25 July 1786) that his “bound Negro slaves” had run away, and he named them: Isaac, from New York, and Flora, Nancy, and Lidge, all of Maryland. He described Nancy as “about 24 years old.” Lidge, a “Negro child” Nancy had with her, may have been her son. Jones explained that they had been “lately brought to this country.” He offered two guineas for each man and six dollars for each woman who was recaptured. The announcement ran in the paper until at least September, suggesting that it was at least three months before Nancy was returned to Jones.

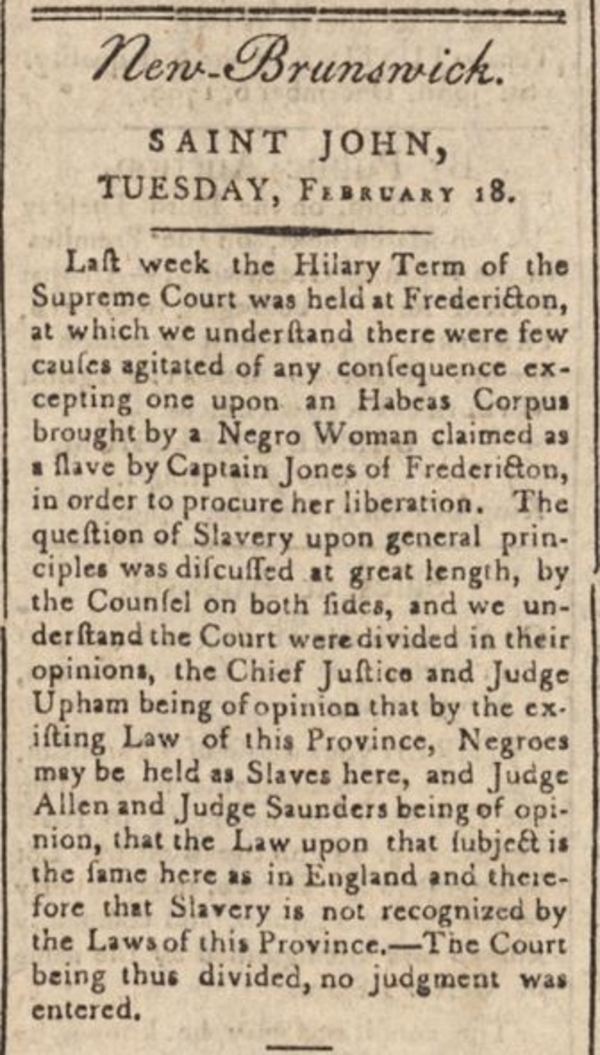

In 1799 Nancy brought a writ of habeas corpus “to procure her liberation,” stated the Royal Gazette (18 Feb. 1800). At trial she was defended pro bono by anti-slavery lawyers Ward Chipman* and Samuel Denny Street*, who would later file a writ of habeas corpus to free Richard Hopefield Jr, the son of Statia*, another enslaved woman. Nancy’s owner, Jones, was represented by Jonathan Bliss*, John Murray Bliss*, William Botsford*, Charles Jeffery Peters*, and Thomas Wetmore*. The case was heard by judges Isaac Allan, George Duncan Ludlow*, John Saunders*, and Joshua Upham*. Of the four, only Saunders did not own slaves; a close reading of his papers suggests, however, that he had interests in the commerce of human beings in Virginia.

The judges were divided in their decision: Allan (who would free his slaves after the case) and Saunders found in Nancy’s favour, with Ludlow and Upham against. She was confirmed as being Caleb Jones’s property. What happened to her after 1800 is not clear. On 16 Oct. 1809 one D. Brown ran an advertisement in the Royal Gazette that offered for sale a “negro wench, named nancy,” which suggests her possible fate. Brown assured prospective purchasers that he had a good title to Nancy.

In 1816, 30 years after he and Nancy had temporarily escaped from Caleb Jones, Lidge also ran away. In the advertisement announcing his flight, Jones described him as “a Negro Slave … under five feet high, broad face and very large lips; brought him from Maryland with my family.” At some point Lidge had acquired knowledge of aquatic travel, for he “took with him a large canoe with a Lathe across her … he was seen going down the River.” Perhaps, in adulthood, Lidge recalled how others had temporarily freed him from Jones and this provided the impetus to run away. It is not clear what happened to him, but Lidge might have escaped permanently since Jones died shortly afterwards, in 1817.

Nancy is an important figure in the history of Canadian slavery. She was enslaved for much of her known life, and after briefly escaping in 1786, she played a central role in a major court case regarding the legality of slavery in the colonial Maritimes. Her story is a case study in how slaves who were exceedingly unhappy in their circumstances did whatever possible to gain freedom.

Nancy’s name and ownership have been confused in the documentary and historical record. The 1786 runaway-slave advertisement submitted by Caleb Jones and documents concerning Nancy’s habeas corpus case (see R. v. Jones, 1799–1800 at PANB, RS32 (Supreme Court, minutes) and RS42 (Supreme Court, case files)) confirm that Nancy (Ann) was owned by Jones and there is no record of a last name.

There is, however, a document dated 27 Feb. 1800 from Stair Agnew*, another New Brunswick slave owner who faced a concurrent habeas corpus case (see R. v. Agnew, 1800–2 at PANB, RS32) regarding his slave Mary. This document calls into question aspects of Nancy’s story. It states that Agnew owned Nancy, whose surname was Morton, and that in February 1800 Agnew was returning her to her former owner, William Bailey, because her title “has become a matter of dispute by [Nancy] claiming her freedom.”

Although the original document has yet to be located, a transcript is found in J. W. Lawrence, The judges of New Brunswick and their times, ed. A. A. Stockton and [W. O. Raymond] (Saint John, 1907; repr., intro. D. G. Bell, Fredericton, 1983). A note following the transcript indicates that on 28 Feb. 1800 “Nancy Morton bound herself to William Bailey for fifteen years.” In his influential article “The loyalists and slavery in New Brunswick,” RSC, Trans., 2nd ser., 4 (1898), sect.ii: 137–85, Isaac Allen Jack* referred to Nancy Morton and the confusion about Agnew’s apparent ownership and her indenture to William Bailey, suggesting that Jack was privy to Agnew’s document before its publication in Lawrence’s book (whether he worked from an original or a transcript is unknown). Historians who relied on Jack have perpetuated the use of the surname Morton and the claim that Nancy was indentured to Bailey.

While the timing of Agnew’s document aligns with Nancy’s court case, it also fits with that of Mary (Mary’s case was in fact held over, pending judgement in R. v. Jones). Without the original record, it is impossible to know whether Lawrence’s transcript is accurate and whether Agnew in fact wrote “Mary Morton.” Nonetheless, there is no other document linking Nancy to Agnew, whereas there are several documents tying her to Caleb Jones.

Univ. of N.B. Library, Arch. & Special Coll., “Return of people settled at the Nashwashes in Block no.1 on land granted to the Maryland Loyalists, 29 July 1785, Caleb Jones,” in Winslow papers: web.lib.unb.ca/winslow (consulted 17 Oct. 2023). Royal Gazette and New Brunswick Advertiser (Saint John), 25 July 1786, 18 Feb. 1800, 16 Oct. 1809. D. B. Harper, “Ambitious Marylander: Caleb Jones and the American Revolution” (ma thesis, Utah State Univ., Logan, 2001).

Cite This Article

Harvey Amani Whitfield, “NANCY (Ann),” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 4, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed April 18, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/nancy_4E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/nancy_4E.html |

| Author of Article: | Harvey Amani Whitfield |

| Title of Article: | NANCY (Ann) |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 4 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of revision: | 2024 |

| Access Date: | April 18, 2025 |