Source: Link

Marguerite (Marguerite Rose (Roze)) (Laurent) (also known as Marie Rose and Mme Rose), enslaved woman, mother, domestic, and entrepreneur; b. c. 1717 in Guinea, West Africa; m. 27 Nov. 1755 Jean-Baptiste Laurent in Louisbourg, Île Royale (Cape Breton Island); d. there 27 Aug. 1757.

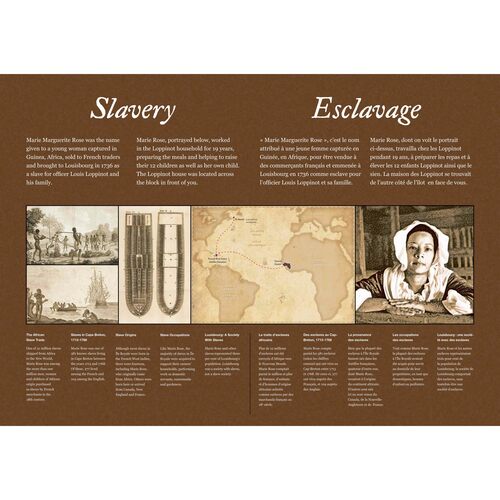

In 1736 Marguerite, approximately 19 years of age, became the property of Jean-Chrysostome Loppinot, an officer of the garrison at Louisbourg. Stripped of her African name, she was baptized there on 27 Sept. 1736 as “Margueritte.” She appears in documents under other names, often as Marguerite Rose; it may be that Rose came to be considered a surname during her lifetime. At least 268 individuals were enslaved on Île Royale between 1713 and 1758, 234 of them in Louisbourg. Few came directly from Africa: the overwhelming majority of the 12,500,000 Africans abducted between the 16th and the 19th centuries were sent to the West Indies, where most soon died; others circulated from there to European possessions throughout the Atlantic basin. The loss of their African names symbolized bondage: the slave trade ensured that people such as Marguerite were separated from their families and communities and deprived of their self-identity. Slavery, writes sociologist Horace Orlando Patterson, entailed “social death,” the elimination of all recognition of previous marks of identity.

Two years after her arrival in Louisbourg, Marguerite gave birth to a son, Jean-François, who automatically became enslaved. The father was listed in the baptismal registration as “unknown.” White Europeans portrayed enslaved women as licentious, but since “masters” owned their slaves’ bodies as a legal right, women in bondage had no defence against sexual exploitation. Of the 70 adult enslaved women identified in French parish records for Île Royale in the period 1722–58, as many as 36 gave birth to a total of 48 illegitimate children. Jean-Francois was almost certainly the son of Jean-Chrysostome Loppinot.

By 1745 the Loppinot family had increased from two to eight children. Marguerite was kept busy cooking, cleaning, and looking after the household, but she had some assistance with these duties from her son. After the capture of Louisbourg that year by New England and British forces under William Pepperrell and Peter Warren, she and Jean-François went with the Loppinots to Rochefort, France. The family returned to Louisbourg in 1749, after Île Royale had been restored to France by the Treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle [see Charles Des Herbiers de La Ralière]. Two years later Marguerite must have suffered great heartache when her son died shortly after his 13th birthday. She persevered and continued to work in the Loppinot household, which eventually numbered 12 offspring, for another four years. After having devoted all of her adult life to domestic chores and child rearing, she obtained her freedom sometime before her wedding in 1755. She was one of only three enslaved women to be manumitted in Île Royale.

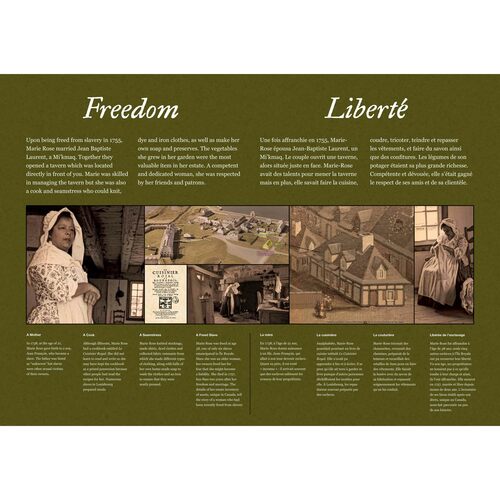

Marguerite and Jean-Baptiste Laurent, as the French knew him, were married in Louisbourg on 27 Nov. 1755. There are eight signatures on the marriage certificate, and most are those of Loppinot’s relatives or fellow officers. The couple’s own friends would have been illiterate. Described in the certificate as an “Indian,” Laurent was undoubtedly a Mi’kmaw: Mi’kmaw people with the same name, including Paul Laurent, lived in Nova Scotia at the time, and their descendants still reside in the province in the 21st century. Oral evidence based on family tradition suggests that there was a degree of interracial acceptance between Indigenous people and Black slaves in Île Royale.

The Laurents’ immediate living conditions are unknown, but five months after their wedding they acquired a two-storey apartment in Block 16 of the town, in a comfortable, half-timbered house that was across from the Loppinots’ own home. The rental agreement notes, “We the undersigned J. Bte Indian and Marguerite Roze Negress, husband and wife, both free[,] have leased a dwelling located on Rue St Louis from [Sieur Bernard Paris] to commence 10 April of the present year [1756] and finish the last of September of the following,” for 50 livres a month. The couple had two rooms downstairs, one with a brick fireplace and four windows, and two upstairs that could be used for sleeping or storage. They had access to the courtyard, which had a well and a garden.

Although Marguerite had lived much of her life in bondage, she had acquired business and management skills. The Laurents opened a tavern in their half of the duplex and they seem to have been equal partners in the business. They obtained supplies from various Louisbourg merchants, lent money, and held receipts for third parties, both signing with their marks on business transactions; Marguerite often appears as “Madame Rose Negress.” The evidence suggests that she sometimes acted apart from her husband in negotiating on behalf of clients, running the tavern, and taking in boarders. She was also responsible, it seems, for paying the rent for the apartment: Paris noted that he received the money from “Marie Rose free Negress.”

Less than two years after her marriage, Marguerite died. Only about 40 years old in 1757, she was nearing the end of her time. Life expectancy for French women in 1750 was just 46.2 years. For enslaved Black people it was much shorter. Historian Marcel Trudel* estimated that in the St Lawrence valley of Canada, in the 200 years before the abolition of slavery in 1834, they lived an average of 25.2 years from birth. Their life expectancy in the West Indies was considerably lower. Manumission became a means of dispensing with the old or sick in many slave-holding societies, and the Loppinots may have decided to free Marguerite because they feared that she might become a liability. Marguerite was of great value, however, and she was costly to replace. In fact, it took two people to fulfil her duties.

On the day of Marguerite’s death, 27 Aug. 1757, the Louisbourg authorities began an inventory of her estate. The resulting document is remarkable, unique in New France since it is the only known inventory for a woman who had been recently freed from slavery. Having proceeded to Marguerite’s apartment in the evening, the officials entered the room facing Rue Saint-Louis. As was typical, they took steps to secure the property. They placed strips of cloth with wax seals on a small chest, on the frame of the window overlooking the courtyard, and on the door of the room. After conducting a cursory inventory, they hired a man and a woman who were watching over Marguerite’s body to ensure that the seals would not be disturbed until a more detailed examination could take place. The whereabouts of Marguerite’s husband at this time are unknown; it may be that he had died.

Six days later, on 2 September, the officials returned. They removed the seal from the chest. It contained most of Marguerite’s wardrobe, as well as much of her husband’s. Her clothing, some of coloured cotton, included a three-piece outfit, a gown, four mantelets, four petticoats, five shirts, a waistcoat, a vest, a cloak with a hood, another cloak hood, 27 coifs and bonnets, a new pair of shoes, a pair each of shoe buckles and garter buckles, ten pairs of stockings (two of silk), and a number of handkerchiefs. Elsewhere the assessors found two additional petticoats, one with a mantelet. Though it was an extensive wardrobe, the clothing was of little value since it was well worn, much of it probably acquired second-hand. Marguerite also had two necklaces, one of pearls and the other of garnets. The cotton fabrics, coloured handkerchiefs, and necklaces reflected her heritage. Brightly dyed cloth, introduced by slave traders, had been popular along the coast of Africa since the beginning of the 16th century. Jewellery was also one of the key items of the slave trade and was so valued that it often served locally in Africa as money.

The apartment was simply furnished. The combined kitchen and dining room included a dilapidated buffet with a dresser on top. There was also a long wooden table with two benches and another table with five straw-bottomed chairs. Approximately thirteen guests could be seated at one time. (Thirteen pewter spoons and thirteen iron forks were discovered in the kitchen, along with a variety of pans, dishes, and goblets.) As was the case with most drinking establishments in Louisbourg, the tavern was a part of the household. The bedroom contained a small table with two drawers and a bedstead in poor condition, with a featherbed, a straw mattress, two woollen blankets, also in poor condition, and “a pair of sheets half worn out.”

Among the foods in Marguerite’s home were coffee (24 pounds), sugar (some 6 pounds), brandy, raspberries, mustard, and “seven to eight hundred walnuts.” There were also 6 pounds of tobacco together with a tobacco mill. She had a significant account, amounting to 226 livres, with Loppinot, who provided her establishment with meat and rum. She purchased salt cod, flour, tafia, and red and white wine from a number of other suppliers. Even though Marguerite was unlettered, she had an inkwell made of horn, a useful item since receipts were usually witnessed by a literate person. She also had a copy of François Massialot’s Le cuisinier roïal et bourgeois…, a cookbook first published in Paris in 1691, likely a prized possession that came from her previous owners. When sold to the highest bidders, the items in the estate went for more than 500 livres.

The inventory of Marguerite’s possessions provides clues to her abilities besides cooking and tavern keeping. Domestic items reveal that she could sew, knit, dye, and iron clothes, as well as make soap. She and her husband were gardeners, as were most residents: she had “a shovel for digging” and the vegetables in her plot were sold for 44 livres, making them the most valuable item in her estate. Laurent was a hunter who had four guns, three powder horns, and a bag of shot among his possessions. The presence of fishing lines with leads suggests that he or his wife fished as well. There are three separate accounts of moneys owed to him by Louisbourg individuals. It is likely that these accounts were for furs. The Mi’kmaq (Micmac) who had been attracted to Father Pierre Maillard’s mission at Île de la Sainte-Famille (Chapel Island) regularly sold pelts to the French at nearby Port-Toulouse (St Peters) and went into Louisbourg as well to deal with merchants there. Although he lived in Louisbourg – one of the few Mi’kmaq to reside among the French – Laurent had the freedom to follow the hunter-gatherer lifestyle.

Enlaved people in Île Royale were forced to adapt to situations they did not choose and could not control. Yet they were individuals with particular life and work skills who established identities for themselves and had a modest but significant presence as a group there. Although robbed of their names and their home communities, they did not remain socially bereft. They formed relationships with the families for whom they worked and the children they tended. They also formed relationships among themselves. Few in number – there were only 125 slaves in 1757, representing 3 per cent of a civilian population of around 4,000 – they would have known each other and may even have collaborated on work in such a small society. Marguerite, however, was the only enslaved woman to be freed and then to open a successful business. She had the trust and the loyalty of her clients (one of whom, a sailor named Thomas Gallien, stayed at the tavern for 32 days in February and March 1756). Most of all, she had the self-respect, competence, and endurance that had enabled her to overcome the brutal demands of slavery.

In 2009 the Historic Sites and Monuments Board of Canada, using the composite name Marie Marguerite Rose, declared Marguerite to be a national historic person, and the following year it unveiled a plaque in her memory at the location of her tavern. Two interpretative panels on either side recognize her role in the Louisbourg story and in Canadian history.

The documentary and other sources for Marguerite’s life are detailed in the author’s articles “Slaves and their owners in Ile Royale, 1713–1760,” Acadiensis (Fredericton), 25 (1995–96), no.1: 3–32, and “Slaves in Île Royale, 1713–1758,” French Colonial Hist. (East Lansing, Mich.), 5 (2004): 25–42. The inventory of her estate is available at Library and Arch. Can. (Ottawa), MG1-G2, file 552, mfm. F-629 (digital copies can be seen at central.bac-lac.gc.ca/.redirect?app=fonandcol&id=3113843&lang=eng); an English translation of the inventory and related documents appears in Graham Reynolds and Wanda Robson, Viola Desmond’s Canada: a history of Blacks and racial segregation in the promised land (Halifax and Winnipeg, 2016), chap.4. See also Ken Donovan, “Female slaves as sexual victims in Île Royale,” Acadiensis, 43 (2014), no.1: 147–56; “A nominal list of slaves and their owners in Ile Royale, 1713–1760,” Nova Scotia Hist. Rev. (Halifax), 16 (1996), no.1: 151–62; “Slavery and freedom in Atlantic Canada’s African diaspora: introduction,” Acadiensis, 43, no.1: 109–15; “Slaves in Cape Breton, 1713–1815,” Canadian Race Relations Foundation, Directions (Toronto), 4 (2007–8), no.1: 44–45; and A. M. Lane Jonah, “Everywoman’s biography: the stories of Marie Marguerite Rose and Jean Dugas at Louisbourg,” Acadiensis, 45 (2016), no.1: 143–62. Also of interest is the Parks Can. podcast episode “Louisbourg: enslavement and freedom at the French fortress,” available at youtu.be/t_mpLwl3e7s (consulted 16 May 2023).

Cite This Article

Ken Donovan, “MARGUERITE (Marguerite Rose (Roze)) (Laurent) (Marie Rose, Mme Rose),” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 3, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed December 29, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/marguerite_3E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/marguerite_3E.html |

| Author of Article: | Ken Donovan |

| Title of Article: | MARGUERITE (Marguerite Rose (Roze)) (Laurent) (Marie Rose, Mme Rose) |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 3 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 2023 |

| Year of revision: | 2023 |

| Access Date: | December 29, 2025 |