Source: Link

JACKSON, LYDIA, indentured Black woman, b. possibly in the early 1760s; d. after 1792.

Little is known about Lydia Jackson’s life. There is conflicting evidence about her origins, her possible children, and even her age (the only source that confirms her existence describes her as a young woman in 1791). The influx of Black loyalists, such as Boston King*, to the Maritimes following the American Revolutionary War suggests that she likely arrived from the United States after 1783. Sometime before the early 1790s her husband left her, so it is impossible to know whether Jackson was her maiden or married name. No woman named Jackson appears in the “Book of Negroes,” a ledger compiled by British officers in 1783 that records the names of 3,000 Black people heading to British North America, but there are two entries for women named Lydia whose surnames are not given, both former slaves from the Carolinas, and another named Lydia Johnson. It is possible that Lydia Jackson was one of them. While it is an important historical source, the “Book of Negroes” is often an inaccurate record of Black people’s names and ages.

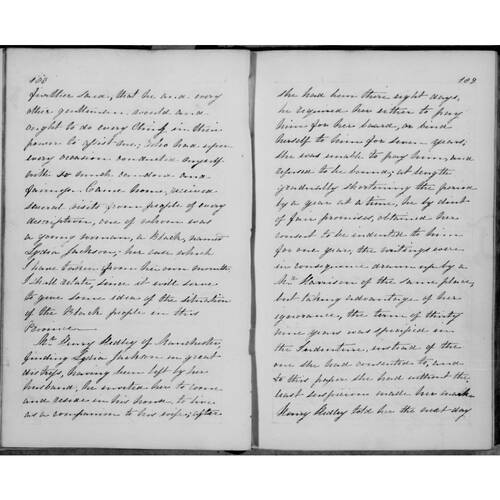

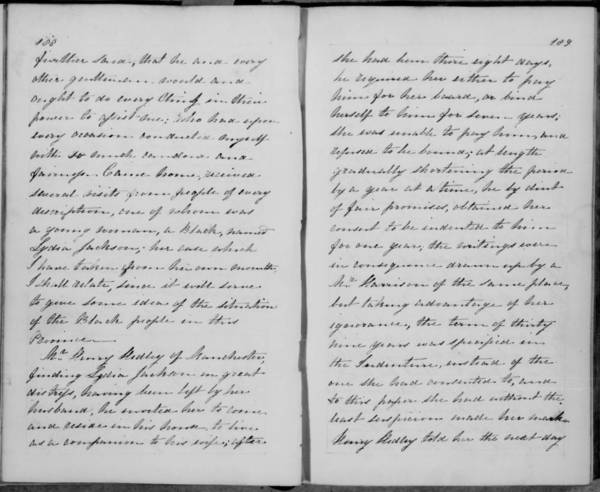

The names of most enslaved Black people in the colonial Maritimes are unknown today [see Name Unrecorded], but Lydia Jackson’s story survives in a 1791 diary entry by John Clarkson. A lieutenant in the Royal Navy and brother of abolitionist Thomas Clarkson, John used the diary to describe his recruiting efforts for the freed-slave colony established by the Sierra Leone Company [see David George*; Thomas Peters]. In Lydia Jackson’s case, Clarkson’s entry shows how tenuous the freedom of Black people could be in colonial Nova Scotia and New Brunswick, where in many instances they were enslaved, freed, and re-enslaved.

Jackson appears to have entered Nova Scotia as a free Black woman and settled in Manchester. When her husband abandoned her, which seems to be the case, she was left “in great distress” and forced to seek out various possibilities for employment. She ended up moving in with a Mr Henry Hedley to serve as a “companion to his wife.” Hedley demanded that Jackson pay rent or agree to be indentured for seven years. Showing a resolve that perhaps defined her personality, she refused, the indenture being tantamount to enslavement. She agreed to stay for only one year. But Hedley, “taking advantage of her ignorance,” had Jackson leave her mark on an agreement for not one, but an outrageous 39 years. The next day he transferred her to a Dr Bulman of Lunenburg, who told her that he had paid £20 – the cost of an adult female slave in Nova Scotia after the American Revolutionary War.

Jackson’s life while enslaved to Bulman was remarkably brutal; she suffered much abuse from him and his wife. According to Clarkson’s diary, Bulman “turned out to be a very bad master” who regularly beat Jackson with “tongs, sticks, pieces of rope &c. about the head & face.” The violence seems to have been spontaneous. On one occasion Jackson spoke to her master without “the least intention of giving offence [but] Bulman took occasion to knock her down, and though she was then in the last month of pregnancy [the child’s paternity is not clear], in the most inhuman manner, stamped upon her whilst she lay upon the ground.” The unborn child probably did not survive; Clarkson does not mention that she had a child when Jackson met him.

Despite the risk of frightful beatings, Jackson tried to obtain help. She approached a local attorney named Lambert, who took her case to court, but because of the “overbearing manners & influence of Bulman,” Lambert and Jackson were “soon silenced.” Bulman threatened to sell her to a buyer in the West Indies as punishment, but instead sent her to work on his farm outside of Lunenburg. He placed her under the purview of his other servants and allowed them to “beat & punish her as they thought fit.”

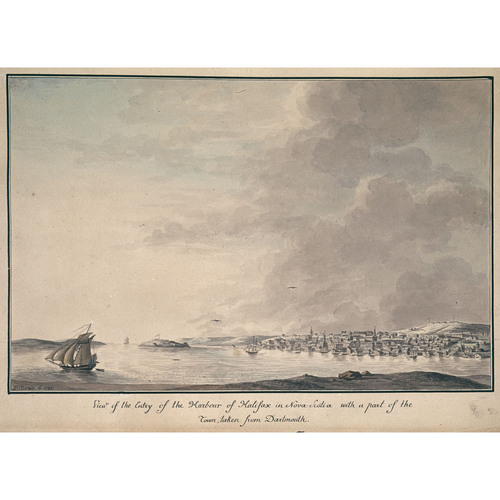

Jackson laboured for three years on the farm before she fled to Halifax, “experiencing innumerable hardships,” according to Clarkson, who described her escape as “wonderful.” Once in Halifax, Jackson attempted to permanently secure her freedom and recoup wages for her work for Bulman and Hedley. She petitioned Lieutenant Governor John Parr, who ignored her, and met with Chief Justice Thomas Andrew Lumisden Strange*, a notable opponent of slavery, who “promised to enquire into the business.” Nothing seems to have come of Strange’s pledge. Following these disappointments, Jackson met John Clarkson, who sought a lawyer in the hope that she could obtain her lost wages. The attorney advised that such a case was unlikely to succeed, and Clarkson suggested she move on.

Although forced to forgo her claims against Bulman and Hedley, Lydia Jackson appears to have succeeded in regaining her freedom. It is likely that soon afterwards she accompanied Clarkson, together with 1,200 Black loyalists, to Sierra Leone. Clarkson admitted in his diary that “I do not know what induced me to mention [Jackson’s] case as I have many others of a similar nature,” but historians can be thankful that he did. Had he not, there would be even less evidence describing how precarious freedom could be for Black people in the colonial Maritimes.

Black slavery in the Maritimes: a history in documents, ed. H. A. Whitfield (Peterborough, Ont., 2018). [John] Clarkson, Clarkson’s mission to America, 1791–1792, ed. and intro. C. B. Fergusson (Halifax, 1971), 89–90. H. A. Whitfield, North to bondage: loyalist slavery in the Maritimes (Vancouver and Toronto, 2016), 88–89.

Cite This Article

Harvey Amani Whitfield, “JACKSON, LYDIA,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 4, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed April 22, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/jackson_lydia_4E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/jackson_lydia_4E.html |

| Author of Article: | Harvey Amani Whitfield |

| Title of Article: | JACKSON, LYDIA |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 4 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of revision: | 2024 |

| Access Date: | April 22, 2025 |