Source: Link

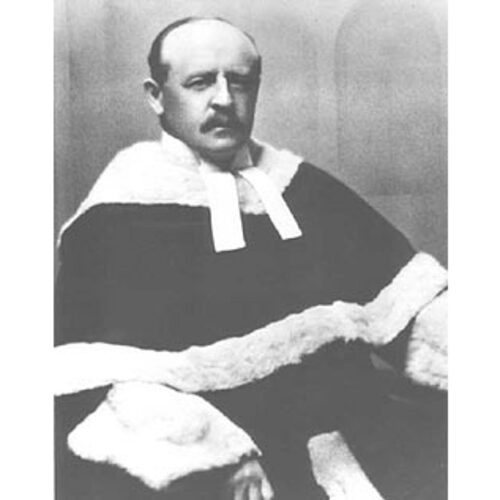

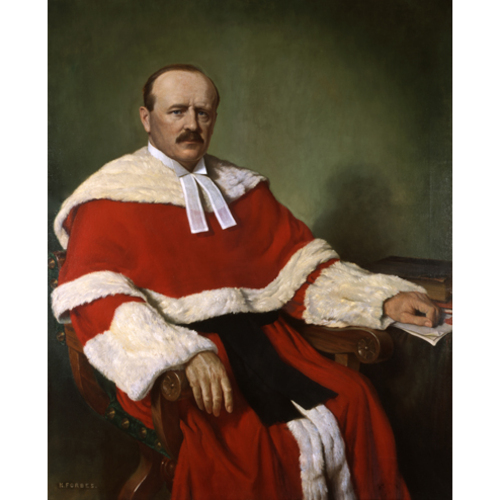

ANGLIN, FRANCIS ALEXANDER, lawyer and judge; b. 2 April 1865 in Saint John, son of Timothy Warren Anglin* and Ellen McTavish; m. 29 June 1892 Harriett Isabell Fraser in Toronto, and they had two sons and three daughters; d. 2 March 1933 in Ottawa.

Frank Anglin’s family immigrated to Saint John in 1849 during the potato famine in Ireland. His father, Timothy, was a noted journalist and spokesman for Irish Roman Catholics in New Brunswick. He founded and wrote for the Weekly Freeman, an important Catholic newspaper in the colony, and at the time of Frank’s birth he was a member of the House of Assembly, fighting unsuccessfully to keep New Brunswick out of confederation. Anglin then won a seat as an independent in the new federal parliament, evolved into a prominent Liberal, and, after Alexander Mackenzie* became prime minister, served as speaker of the house from 1874 to 1878. His second wife, Ellen, bore ten children, of whom Frank was the eldest.

The Anglins were a talented family. Frank’s brother Arthur Whyte would become a prominent lawyer; two of his sisters, Mary Margaret* and Eileen, were to gain fame as stage actresses, and Margaret was Canada’s first Broadway star, touring in North America and Australia. Frank was an excellent singer. He considered a career in music, and after going into law he was a baritone soloist for many years with various choral groups. Also a composer, he performed his own settings of Salve Regina (with solo for mezzo-soprano or baritone) and Ave Maria at St Michael’s Cathedral in Toronto, where he often sang at key events.

Frank and Arthur attended the Jesuit-run, bilingual Collège Sainte-Marie in Montreal and then the College of Ottawa, from which Frank graduated with a ba in 1885. The two brothers then came to Toronto for lectures at Osgoode Hall law school, and through their father’s Liberal connections they served as articled clerks at Blake, Lash, and Cassels, the firm of Edward Blake* and Zebulon Aiton Lash*. They were both excellent students: Frank was called to the bar in 1888, winning a silver medal in his bar examination, and Arthur won gold two years later. They decided to practise law in Toronto, but their careers diverged dramatically. Frank went into partnership with Dennis Ambrose O’Sullivan*, a prominent Catholic, and served his own religious community, while Arthur remained with the institution that would become Blake, Lash, Anglin, and Cassels, one of several establishment firms that dealt with the city’s largely Protestant business class. As a result, Frank was never as busy or financially successful in practice as Arthur.

In 1892 Frank Anglin married Harriett Isabell Fraser. When his father had written to inform John Sweeny*, bishop of Saint John, of the pending union, he noted that his eldest son did not yet have a large income, “but he is very industrious and attentive to business and has big expectations.” O’Sullivan died that year, and shortly thereafter Anglin joined in partnership with George Dyett Minty. That arrangement did not last, and by 1894 Anglin had founded a new firm with James Woods Mallon, a graduate from the University of Toronto, under the name Anglin and Mallon. They had a mixed practice, doing some commercial and estates work as solicitors and carrying out civil litigation as barristers; they also arranged loans and mortgages for clients, and they lent money at low rates. The firm enjoyed only modest success, however, and both partners began to look for a more secure source of income. After Timothy Anglin died in May 1896, Frank assumed his father’s position as clerk of the Surrogate Court of Ontario. He held this job for three years to supplement his earnings, and also sought out work as a crown prosecutor in a number of criminal cases.

Anglin was able to secure these appointments because of his political connections. Following in his father’s footsteps, he had become an active Liberal early in his life. He briefly thought about a political career, and in 1895 he was supported by party leader Wilfrid Laurier* as the prospective Liberal candidate in Renfrew South. When he did not win the nomination, he ceased seeking public office. He had seen the plight of his father, a fiery advocate and former speaker of the house who struggled to find work later in life (in fact, Frank and Arthur had likely persuaded the government of Sir Oliver Mowat* to give their father his clerkship).

Still, Anglin remained a staunch supporter of the party. He was an indefatigable campaigner and an excellent speaker: in the federal election of 1896, for example, the successful Liberal standard-bearer in Perth South, Dilman Kinsey Erb, reported that Anglin’s speech on his behalf was “the best he had heard during the campaign.” After that contest Anglin was listed by the Toronto Daily Star as one of the “prominent politicians” who were in Ottawa while Laurier, the new prime minister, was forming his cabinet. What made Anglin especially valuable to the party was that, like his father before him, he was a spokesman for the Irish Catholic community. The press sought out his expert commentary on such controversies as the Manitoba school question [see Thomas Greenway*], and he presided at functions honouring the clergy, sang at the funerals of prominent co-religionists, and represented the Catholic separate schools on the Toronto Board of Education.

These political activities were to some extent a means to an end for Anglin, who hoped to persuade Laurier to make him a judge. He was genuinely interested in the law and authored many articles on legal questions as well as a book, Limitations of actions against trustees and relief from liability for technical breaches of trust (Toronto, 1900). He believed that he would make a good judge and knew that Catholics were under-represented on the bench in Ontario (at the turn of the century they held six judgeships, less than 10 per cent of the overall number in the province, despite the fact that Catholics made up almost 18 per cent of the population). In 1897 he began writing letters to Laurier seeking a judicial position and encouraged other Irish Catholics to lobby the prime minister on his behalf. His supporters included the archbishops of Toronto, Ottawa, and Kingston, the bishops of Alexandria, Peterborough, and Pembroke, numerous parish priests, and several mps. There were so many of these letter writers, in fact, that in 1900 Laurier finally warned one of them, “If he continues to badger me with letters from all parts of the province, I will refuse point blank to appoint him.” Anglin got the message. He started to put more effort into raising his profile and doing favours for the Liberal Party, and this tactic seems to have worked. He was made a kc in 1902 and sat that year as a substitute judge in Gore Bay, filling in for Thomas Ferguson of Ontario’s High Court of Justice.

In 1903 James Mallon left the firm of Anglin and Mallon and started to work in the provincial Department of the Attorney General as inspector of legal offices and registry offices. He thus finally gained the secure source of income that he had long desired. Anglin was not far behind in doing so himself. That year a fourth division of the High Court of Justice, the Exchequer Division, was created by the Ontario government. This expansion opened up three new judicial positions, and Anglin was awarded one of them the following year, as was John Idington* of Stratford. At 63 years of age Idington was considerably older than Anglin, who at 39 was one of the youngest judges in Ontario. Both men would soon find themselves sitting on the Supreme Court of Canada. Idington was promoted after only a year on the High Court; Anglin stayed there for five years and proved himself both energetic and able. He heard numerous cases, wrote well-received judgements, and even found time in 1906 to serve as a commissioner for the revision of the province’s statutes.

In early 1909 James Maclennan, a justice of the Supreme Court, retired at age 75. His place was first offered to Featherston Osler, the senior puisne justice of the Ontario Court of Appeal, but Osler, who was near retirement, declined the appointment. On 23 February Anglin was thus named to Canada’s highest court. The Canadian Law Times stated that as a judge, he had “given every satisfaction to the legal profession. He has been uniformly courteous, and often at much inconvenience to himself, he has undertaken work in which the legal profession is deeply interested. His removal to the Supreme Court at Ottawa is a distinct loss to the Bench of Ontario.”

Anglin gave a strong early indication that he would be a conservative member of the Supreme Court. In Stuart v. Bank of Montreal (1909) he, along with Chief Justice Sir Charles Fitzpatrick*, Sir Louis Henry Davies*, and Lyman Poore Duff*, formed the majority who held that the court was bound by a previous decision even though there was a valid basis upon which the earlier ruling could have been distinguished. Five years later, in Quong-Wing v. the King, the same judges relied on a previous ruling of the court to deny a challenge to Saskatchewan legislation that prohibited the employment of white women in places of business or amusement kept or managed by “Chinamen.” The issue, the court pointed out, was not whether it approved of the law, but whether the province’s legislature had the right to enact it. Idington, showing his independence, disagreed with both decisions. Anglin’s formalistic approach, and Idington’s dissent from it, would prove to be a common feature of subsequent Supreme Court judgements.

Although Anglin was a cautious, tradition-bound judge, he was not against all change. In 1910, for example, even though he had been on the court for only one year, he proposed an alteration of its structure that would have allowed the appointment of ad hoc judges to assist with the court’s workload in cases where illness or a leave of absence caused problems. He learned, however, that this innovation would not be welcome, and his suggestion was ignored by the Laurier government.

The judgements of the Supreme Court were at times politically sensitive, and in these instances Anglin generally sided with the government. One such case arose in 1918 when an exemption from conscription granted by the government of Sir Robert Laird Borden to George Edwin Gray, a young, unmarried farmer in northern Ontario, was revoked in April 1918 by an order in council of the federal cabinet. Gray refused to serve and was arrested. He then applied for a writ of habeas corpus, alleging that parliament’s delegation of its legislative powers to the cabinet under the War Measures Act of 1914 was unconstitutional and the order in council therefore invalid. Anglin was visited in chambers by the deputy minister of justice, Edmund Leslie Newcombe, who wanted Gray’s application to be heard by the whole Supreme Court to obtain a binding ruling. Anglin issued the requested summons, which was then printed in the Globe. The case was heard on 18 July 1918 with all six justices sitting. Only Idington sided with Gray. Anglin joined the rest of the court in holding the delegation of powers under the War Measures Act to be valid. Chief Justice Fitzpatrick, writing for the majority, gave a chilling justification for its ruling, arguing that “the safety of the country is the supreme law against which no other law can prevail.” The Gray decision was one of Fitzpatrick’s last judgements. In October 1918 he resigned, and though there was some suggestion that Anglin might be chosen to replace him, the much older and more experienced Davies was selected instead.

Anglin took a bold stand in favour of a strong federal government in the case In re Board of Commerce Act (1920). At issue was the Combines and Fair Prices Act, 1919, which authorized a board of commerce to inquire into and, if appropriate, prohibit profiteering in the sale of the necessities of life [see William Francis O’Connor]. The Supreme Court was split evenly over the question of whether the federal government had the right to enact such legislation. Anglin wrote a powerful judgement that upheld the legislation under the federal power over trade and commerce and the federal residual power (the “Peace, Order, and good Government” clause), but the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council (JCPC) in London, England, disagreed and ruled the act unconstitutional. Many scholars have since supported Anglin’s judgement and consider its reversal by the JCPC to have been wrong.

Anglin’s judgement in the radio reference case (1931) would be better received by the JCPC. The federal government referred the constitutionality of its Radiotelegraph Act, which placed radio communication under federal control, to the Supreme Court. The legislation was upheld by Anglin, Newcombe, and Robert Smith, with John Henderson Lamont and Thibaudeau Rinfret* dissenting. Anglin concluded that because radio communication was not expressly dealt with in the British North America Act of 1867, it fell under the federal residual power and was not, as Quebec had contended, within provincial jurisdiction. He also declared, more contentiously, that federal regulation of this technology was a necessity. The JCPC agreed with the Supreme Court’s ruling on the basis of Anglin’s first opinion.

Anglin, who was fluently bilingual, was sensitive to the fact that the Supreme Court was required to rule on matters relating to the Quebec Civil Code even though he and the majority of the court’s members were trained only in common law. In Desrosiers v. R (1920) his written majority judgement held that English common-law decisions were not to be cited as authorities in Quebec cases that did not depend upon doctrines derived from English law. From this point forward, Anglin consistently backed his French-speaking colleagues in their handling of Civil Code cases.

In 1923 Anglin was Canada’s nominee for the International Court of Justice in The Hague. He was not selected; however, a greater honour much closer to home was about to be offered to him. By early 1924 Sir Louis Davies was too ill to continue as chief justice, and Prime Minister William Lyon Mackenzie King* began to consider his successor. Eugene Lafleur*, a distinguished but elderly counsel from Montreal, was the first choice. Lafleur declined, but King did not want to take no for an answer and asked Governor General Lord Byng to persuade him to accept. When Davies died on 1 May, the prime minister had still not secured Lafleur’s agreement. On 8 September King pleaded with Lafleur (“you are the one man in Canada who could meet … our country’s most imperative need”), but again he refused.

Many commentators questioned why the prime minister had not simply appointed Lyman Duff, who was widely considered to be the best judge on the court. Certainly Duff had earned international acclaim: in 1919 he had been named to the JCPC, the only Canadian puisne justice ever to be so honoured, and he had been made an official visitor at the prestigious Harvard Law School. King, however, distrusted Duff’s sympathy for the Conservative Party and regarded him, with some justification, as an alcoholic. On 12 September King noted in his diary that Anglin, a logical alternative nominee as chief justice, was “narrow, has not a pleasant manner, is very vain, but industrious steady and honest, a true liberal at heart.” Exactly what King found disagreeable about Anglin’s manner is unclear, but years later Charles Murphy, an Irish Catholic mp from Ottawa, would confide to a friend that Anglin was widely known as “Chief Paw-Knee” and the “Garter-Snapper.” Murphy added that he “had never heard of his contributing anything of a constructive or helpful nature to anything, or anybody, that was Irish,” and implied that Anglin had embraced his heritage as a means of advancing his career.

Despite his reservations, King reluctantly decided to offer the position to Anglin, who was sworn in as chief justice of the Supreme Court of Canada on 16 Sept. 1924. His relations with Duff, with whom he had never been friends, became even more distant. However, not all were unhappy with the appointment. Pope Pius XI made Anglin a knight commander of the Order of St Gregory the Great, and would elevate him six years later to the rank of knight grand cross of that order. Anglin himself was pleased, of course: he had always been ambitious, and he took the promotion to chief justice as an acknowledgement of his worth on the Supreme Court. These years were a heady time for him. In 1925 he was elected a bencher of the Inner Temple in London, a rare honour for a Canadian judge, and the next year he was presented to King George V and Queen Mary at Buckingham Palace. When Governor General Lord Willingdon [Freeman-Thomas*] was away from Canada in 1927, Anglin became his deputy and was referred to as “His Excellency.” When Anglin’s sister Margaret, now a star on Broadway, came to visit, they were able to share in each other’s success.

One thing that displeased Anglin was the fact that his court played second fiddle to the JCPC in England. It bothered him that rulings of Canada’s highest court could be overturned by judges outside the country. It troubled him even more that it was possible, with leave, to bring the judgement of any provincial court of appeal directly to the Privy Council, bypassing the Supreme Court entirely. It did not matter to Anglin that, as chief justice, he had been appointed a member of the JCPC and could sit on this ultimate appellate body. He believed strongly that his court ought to be the final court of appeal for Canada. In 1926 he sent a memorandum to King that called for the termination of the JCPC’s role, arguing that as a self-governing and effectively independent nation, Canada should settle its litigation on its own soil. Nothing came of his request, and it would be another 23 years before appeals to the JCPC were ended.

Anglin took pride in his judgements, which were carefully researched, well crafted, and firmly based on legal precedent. It hurt him deeply when others criticized his work and cast it aside, as happened in the persons case, which asked the Supreme Court to consider whether women were “qualified persons” eligible to sit in the Senate. The case arose in 1928 out of the lobbying of five women: Henrietta Louise Edwards [Muir], Mary Irene Parlby [Marryat*], Helen Letitia McClung [Mooney*], Louise McKinney [Crummy], and Emily Gowan Murphy [Ferguson]. They retained Newton Wesley Rowell* as their counsel. Anglin did not deny that women were persons. “There can be no doubt,” he conceded, “that the word ‘persons’ when standing alone prima facie includes women.” But here the word did not stand alone; it was part of the phrase “qualified persons.” In concluding that women were not qualified to sit in the Senate, he relied upon earlier decisions of courts in the British empire. The other justices – Duff, Lamont, Smith, and Pierre-Basile Mignault* – agreed with his decision and chose to give a strictly correct judgement in keeping with the law as it was then understood. If there was to be a change, they thought, it should come from parliament rather than from the Supreme Court.

On appeal, however, Lord Sankey of the JCPC thought differently. He criticized Anglin for “a narrow and technical construction” of the question, and instead favoured a “large and liberal interpretation” of the Canadian constitution, which he called “a living tree capable of growth and expansion within its natural limits.” Sankey thus reversed the decision. Anglin was not pleased. This result was exactly the kind of outcome he had sought to prevent by proposing the termination of appeals to the JCPC: a foreign court had effectively amended the Canadian constitution without due political process.

Unable to challenge the ruling himself, Anglin encouraged George Frederick Henderson, a prominent Ottawa lawyer, to write a scathing article in the Canadian Bar Review (Toronto). In defending Anglin’s approach, Henderson noted that the Supreme Court was bound by legal precedent, in sharp contrast to the JCPC, which looked to public policy and political expediency. Anglin reluctantly accepted Sankey’s decision, but did his best to limit its application. When the 1931 case Town of Montreal West v. Hough asked the Supreme Court to give the mother of an illegitimate child the right to sue for damages suffered in the death of the child on the basis that society’s attitudes towards such children had changed, Anglin declined to do so. Alluding to Henderson’s article, he stated that “the courts must await the action of the legislature, whose exclusive province it is to determine what should be the law.”

For at least two years Anglin had been unwell. In 1929 he had taken a leave of absence, hoping that a lengthy stay in the Caribbean would restore him to good health, but it did not. That fall King noted that the chief justice was “failing” and had “lost all his brightness.” Over the next three years Anglin applied for and received further leaves. Rumours that he was incapacitated began to circulate. He knew of them, and was sensitive to what he perceived as efforts to oust him in favour of Lyman Duff. In 1932 Governor General Lord Bessborough [Ponsonby*] went on a viceregal tour and designated Duff as his deputy because Anglin was out of the country. When the chief justice returned earlier than expected, he was so upset that he wrote a formal letter of protest, alleging that the governor general had no right to appoint anyone other than himself.

In January 1933 King, now leader of the opposition, wrote in his diary that Anglin could not speak, and predicted that he would not last long. “It is quite sad,” King added, “to see a man give up his life work. Anglin is only 68, – a fine intellect, but too vain.” The government of Prime Minister Richard Bedford Bennett* was legitimately concerned that the chief justice could no longer carry out his duties, and suggested to Anglin that if he did not leave office, an investigation into his capabilities would have to be launched. Faced with that prospect, Anglin submitted his resignation. He died two days after it took effect.

Minister of Justice Hugh Guthrie stated at the time of Frank Anglin’s death that his many judgements would “long stand as landmarks in Canadian jurisprudence.” But this assessment has not been proved accurate. To the extent that Anglin is remembered at all, it is as a hard-working, competent, but unimaginative legal technician. His written opinion in the persons case is one of the most criticized and ridiculed decisions ever made by the Supreme Court. Regrettably, it has become his legacy.

In addition to writing the book noted in the text, Francis Alexander Anglin is the composer of Salve Regina (Saviour, have mercy): solo for mezzo-soprano or baritone (Toronto, 1900) and Ave Maria, infant redeemer: song (Toronto, 1902), as well as the author of several legal articles, including “Mortgagee, mortgagor and assignee of the equity of redemption,” Canadian Law Times (Toronto), 14 (1894): 57–77; “Revival by codicil,” Canadian Law Times, 18 (1898): 25–39, 49–61; “Extra-territorial criminal legislation of Canada,” Canadian Law Times, 19 (1899): 1–19, 38–45; and “The extinguishment of easements,” Canadian Law Times, 20 (1900): 279–93. A complete list of his publications is held in the Anglin file at the DCB offices.

LAC, R4923-0-0, Charles Murphy to Emmet J. Mullally, 8 April 1935; R10811-0-X. Law Soc. of Upper Can. Arch. (Toronto), 1-5-1-2 (Convocation fonds, common, barristers’ and benchers rolls); 1-5-5 (Convocation fonds, attorneys rolls 1849–1892 common pleas); PF79 (James Woods Mallon fonds). Globe, 11, 18 Feb., 2 April 1895; 5 May, 3 Nov. 1896; 5 Aug., 14 Oct., 30 Nov. 1898; 10, 16, 23 March 1904; 14 Feb., 3 March 1933. Toronto Daily Star, 21 March, 10 July 1896; 11 Oct. 1897; 5 Feb. 1898; 5 Nov., 27 Dec. 1900; 18 Sept., 27 Oct. 1924; 13 Feb., 4 March 1933. W. M. Baker, Timothy Warren Anglin, 1822–96: Irish Catholic Canadian (Toronto and Buffalo, N.Y., 1977). Robert Brown, The house that Blakes built (Toronto, 1980; copy at the Law Soc. of Upper Can. Arch.). The Canadian law list (Toronto), 1890, 1895, 1900. Canadian men and women of the time (Morgan; 1912). National encyclopedia of Canadian biography, ed. J. E. Middleton and W. S. Downs (2v., Toronto, 1935–37), 1. “Promotion of Mr. Justice Anglin,” Canadian Law Times, 29 (1909): 304. R. J. Sharpe and P. I. McMahon, The persons case: the origins and legacy of the fight for legal personhood (Toronto and Buffalo, 2007). J. G. Snell, “Frank Anglin joins the bench: a study of judicial patronage, 1897–1904,” Osgoode Hall Law Journal (Toronto), 18 (1980): 664–73. J. G. Snell and Frederick Vaughan, The Supreme Court of Canada: history of the institution ([Toronto], 1985). Standard dict. of Canadian biog. (Roberts and Tunnell), vol.1. Supreme Court of Can., The Supreme Court of Canada and its justices, 1875–2000: a commemorative book ([Toronto], 2000). D. R. Williams, Duff: a life in the law (Vancouver, 1984); “Eugene Lafleur,” in his Just lawyers: seven portraits (Toronto, 1995), 18–55.

Cite This Article

C. Ian Kyer, “ANGLIN, FRANCIS ALEXANDER,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 16, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed April 29, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/anglin_francis_alexander_16E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/anglin_francis_alexander_16E.html |

| Author of Article: | C. Ian Kyer |

| Title of Article: | ANGLIN, FRANCIS ALEXANDER |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 16 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of revision: | 2019 |

| Access Date: | April 29, 2025 |