Source: Link

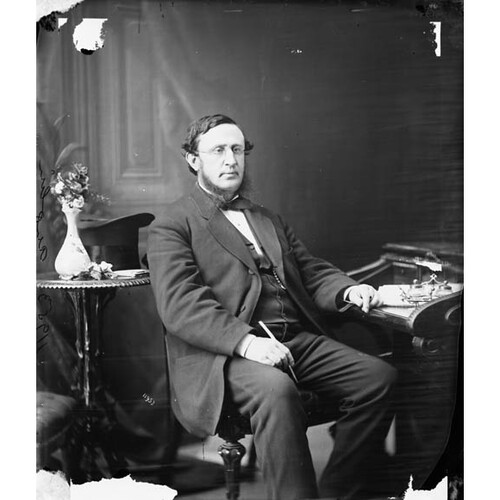

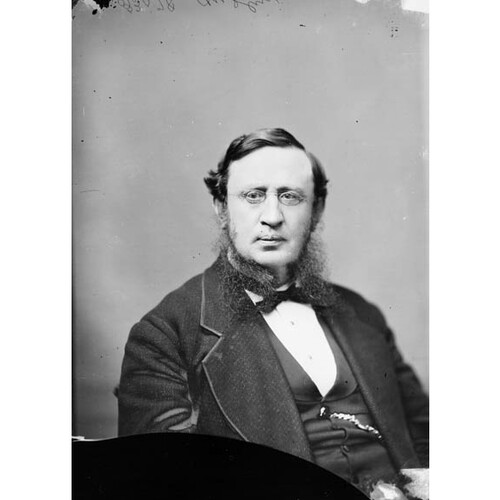

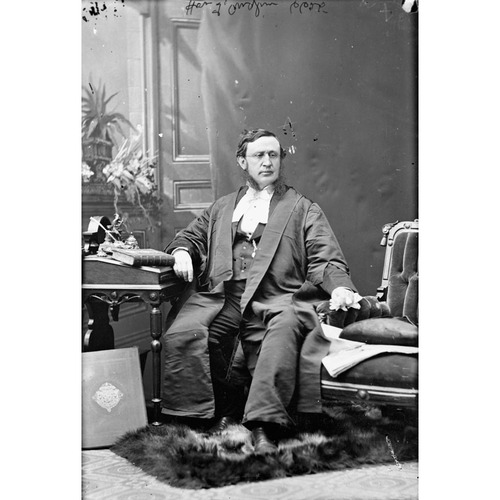

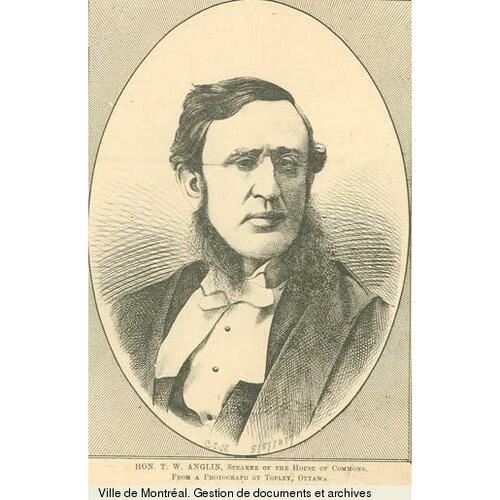

ANGLIN, TIMOTHY WARREN, journalist, publisher, politician, and office holder; b. 31 Aug. 1822 in Clonakilty (Republic of Ireland), son of Francis Anglin, an employee of the East India Company, and Joanna Warren; m. first 1853, probably on 26 November, in Saint John, N.B., Margaret O’Regan (d. 1855); they had no children; m. there secondly 25 Sept. 1862 Ellen McTavish, and they had ten children; d. 3 May 1896 in Toronto.

Timothy Warren Anglin was born into a relatively wealthy middle-class Irish Catholic family in County Cork and received a good classical education in Clonakilty. His plans to prepare for a legal career were interrupted when the Great Famine hit Ireland in 1845 and he was forced to take up school teaching in his home town. On Easter Monday 1849 he left Ireland for Saint John, evidently considering that emigration would increase his opportunities. His Irish, Roman Catholic, middle-class upbringing influenced Anglin throughout his life and shaped his career as an articulate spokesman for Irish Catholics in New Brunswick and Canada.

Anglin’s introduction to public life in Saint John came shortly after his arrival. In response to a violent 12th of July riot he wrote a lengthy letter to the Morning News of that city deploring sectarian strife, criticizing municipal authorities for allowing events to get out of hand, and urging all to remain calm and to cooperate for the benefit of the colony. The letter brought Anglin to the notice of the public and reinforced what was probably a preconceived plan to establish a newspaper. On 4 August the first issue of the Saint John Weekly Freeman appeared, dedicated to enhancing the position of Irish Catholics in the city.

During the 1850s Anglin, through his newspaper, became the acknowledged lay spokesman for this large group, which comprised approximately one-third of the city’s population. As the most impoverished segment of any size, the Irish Catholics suffered proportionately more than others from low wages, unemployment, inadequate housing, and disease. They faced various forms of economic, social, political, and religious discrimination and were viewed by “respectable” citizens as being prone to drunkenness, profligacy, and violence. Anglin’s approach as an Irish Catholic leader was multi-faceted. He defended them against charges that they were depraved and a burden on society. He promoted their self-respect by providing news from Ireland, by supporting the organization of ethno-religious groups, such as the Irish Friendly Society, and by encouraging the development of Catholic welfare societies. But he also encouraged them to improve and transform themselves with God’s help. Instances of rowdyism, wretched cases of immorality, examples of street urchins “trained to begging as a profession, by parents who are too idle to work, or too dissipated and worthless to support their family on their earnings,” all received a lashing in the Freeman. In his strictures Anglin might be considered lacking in compassion and understanding but, from his perspective, if Irish Catholics were to be accepted they had to avoid activities that threatened the social fabric or made dominant groups fearful. He felt compelled to “improve” them in order to make more legitimate his case for increased recognition and rights. Anglin’s approach was very much middle class, promoted by the church and tempered by some realization of the impoverished conditions in which many lived. Even his economic philosophy was fairly typical 19th-century laissez-faire individualism. Certainly he favoured the development of various enterprises in and around Saint John as a means of providing employment for Irish Catholics, but he believed that the fundamental rules of the game ought to be those of free-enterprise capitalism.

While the Freeman was never a great financial success, it did become a major presence in the political life of New Brunswick during the 1850s and remained Anglin’s main public platform for a quarter century. He entered into the prevailing “slash and stab” style of political journalism with relish and skill. Initially the Freeman supported the reformers, or Smashers as they were sometimes known, but after they formed the government in 1854 under Charles Fisher*, Anglin became disenchanted. The new administration proved to be no more generous towards Catholics than the old, and the 1855 bill banning liquor except for medicinal purposes outraged Anglin as a gross infringement on civil rights. He broke with the Smashers and remained in opposition even after prohibition was repealed in 1856. Indeed, Anglin always seemed more comfortable in the ranks of those opposed to the government; he was more of an independent than a true party supporter, no doubt in part because he had particular interests to serve as an Irish Catholic leader, but also because he thought it “much easier and more pleasant” to attack than to defend.

Anglin’s first effort to gain political office, his attempt in 1860 to win an aldermanic seat on the Saint John Common Council, was a failure, but in 1861 he was elected to the New Brunswick House of Assembly for Saint John County and City as an independent. Throughout his career Anglin’s political thought was pragmatic, but in essence he was a lukewarm democrat and a liberal. He supported the extension of the franchise, the secret ballot, and simultaneous elections, but he balanced his democratic leanings with liberalism, that British middle-class doctrine of laissez-faire individualism. He argued that liberal ideals were to be realized less through specific political systems or legislative programs and more through the maintenance of justice and freedom for the individual whatever the form of government. “Where the rights of the individual are trampled upon there is despotism,” he wrote. In his view, the problems of society would be solved, not by the use of state power, but by the influence of religion.

For British North Americans the 1860s were shaped by the American Civil War and its aftermath. Anglin found much to criticize in the sentiments, concepts, and behaviour of the leaders and citizens of the republic; yet he found no cause for rejoicing in its difficulties. He believed that the destruction of the United States would be a tragedy for the entire world. Moreover, in contrast to so many British North Americans, he could see no great constitutional lesson to be learned from the war. The fault lay not with republicanism or the particular form of American federalism, but with the institution of slavery and the fanaticism which existed in both the North and the South.

The war raised the question of colonial defence and the imperial connection. Anglin developed a compartmentalized attitude towards Britain; although he never accepted British domination of Ireland, he did learn that it was not necessary or just to criticize the imperial connection from the British North American point of view. It provided the best defence against any aggressive American attempts to take over the colonies. Anglin was at pains to point out that British North Americans, including Irish Catholics, had no desire to be incorporated into the American republic. But, since the colonies were innocent bystanders in quarrels between Britain and the United States, the mother country ought to bear the brunt of the organization and expenditures necessary for their defence.

The atmosphere of crisis engendered by the war, combined with economic and political difficulties in the colonies, led British officials and many colonials to embrace the idea of British North American union. Anglin was not enamoured of the concept, although he believed union both likely and desirable at some point in the future, especially if Britain broke the imperial connection. But at the time, Anglin considered it neither necessary nor desirable. It would not bring military strength or wonderful economic advantages, at least not for common folk and certainly not for residents of Saint John or New Brunswick. The main beneficiaries, he claimed, would be central Canadian politicians and businessmen whose extravagance, extremism, and incompetence had created the colonies’ difficulties in the first place. Far better for public men to involve themselves in promoting essential, if mundane, material development such as building roads, assisting settlers, and removing barriers to mercantile activity than to indulge in “chimeras and fancies at the public expense.”

Given Anglin’s view that the very idea of union was premature, it is hardly surprising he opposed the particular version of it which emerged in the Quebec resolutions of 1864. The Freeman was especially critical of the economic implications, arguing that the fiscal arrangements were not fair to New Brunswick, that import tariffs would have to be increased, that Saint John would lag behind in transportation and manufacturing developments, and so forth. As for the constitutional arrangements, Anglin considered the plan to be one of legislative union providing no substantial defence for the special interests of New Brunswick. In addition, he was outraged at the intent of the Quebec conference delegates to submit the arrangement, not to the electorate at large, but simply to the colonial legislatures: “This is clearly a conspiracy to defraud and cheat the people out of the right to determine for themselves whether this Union shall now take place.”

Circumstances in New Brunswick forced the government, led by Samuel Leonard Tilley, to call an election early in 1865. Through the columns of the Freeman and in person Anglin waged a hard and skilful battle and emerged as one of the most prominent anti-confederates. Majority opinion in New Brunswick agreed with Anglin’s opposition to the union proposal and the government went down to a resounding defeat. Confederates blamed their failure on many factors but they attributed it especially to a conspiracy organized by clerics and by laymen such as Anglin, which they believed had led Catholics to vote en bloc against them. This view played an important role in shaping the confederates’ tactics in their continuing quest for union, but it was erroneous. Not only is it doubtful that Catholics did vote in such a manner, but it is also quite clear that the hierarchy made no concerted effort to mould a block Catholic vote.

Anglin became an executive councillor without departmental office in the anti-confederate government formed in April 1865 under Albert James Smith* and Robert Duncan Wilmot. From the beginning that administration was beset with difficulties. Its strength was undermined by an economic downturn, by obstruction from the Legislative Council, and by its own internal division: some members of cabinet had opposed the Quebec resolutions on the grounds that they gave too much power to the provinces, while others thought they gave too little. In addition, those who rejected confederation were accused of disloyalty, especially after imperial authorities proclaimed that it was highly desirable particularly for purposes of defence. Anglin, the Irish Catholic, was the focus of the confederates’ “loyalty” campaign from the start; although he appears to have been a conscientious and useful member of the cabinet, he was a prime target for attacks on the government. One newspaper called his very appointment “an imposition on, and an insult to every loyal protestant subject of Her Majesty in this Province.” Anglin asserted that in opposing confederation there was no disloyalty to the empire, but he could not quash the charge for it was of political utility to the confederates.

The loyalty issue became even more crucial in the autumn of 1865 when the Fenian menace began to appear serious. The American branch of the Fenian movement, bent on liberating Ireland from Britain, proposed to attack Britain’s colonies in North America. Neither Anglin nor the vast majority of New Brunswick’s Irish Catholics were Fenians or even Fenian sympathizers, though Anglin and others undoubtedly supported the goal of greater freedom for Ireland. None the less, the approach of confederates in New Brunswick was to create the image of two opposing forces in the colony: loyal, Protestant, confederates versus Fenian-sympathizing, anti-confederate, Catholics led by Anglin. This tactic proved highly successful in the York by-election of November 1865, when confederate Charles Fisher defeated John Pickard*. Shortly thereafter Anglin resigned his cabinet post, partly because of the enormous abuse he was receiving but mainly because he no longer believed that the government was doing enough to ensure construction of a railway line from Saint John to Portland, Maine. However, he continued to give general support to the government and remained a prominent opponent of confederation.

For many reasons, the position of the government became progressively weaker. Most significantly, the confederates went on making effective use of the loyalty issue, mightily aided by a comic-opera Fenian raid on New Brunswick in April 1866. The lieutenant governor, Arthur Hamilton Gordon*, took advantage of this crisis and the enfeebled state of the government to force a change in the ministry. In the election which followed in May and June, the anti-confederates were soundly defeated, Anglin included. According to one New Brunswick newspaper, the results meant that “Fenianism and Annexation, or, in one word, Warren-Anglinism was ‘taken in and done for,’ and the disloyal Fenian sympathizing brood fairly squelched.” For his part, Anglin thought that “the conspirators” had won.

In his opposition to confederation, Anglin had presented many arguments that were particularly sensible when viewed from the perspective of Saint John. Moreover he was quite justified in his objection to the tactics employed by British officials and by New Brunswick confederates. But in examining the union proposal Anglin seems to have been unwilling to accept anything less than perfection. If he supported the general concept as he claimed he did, he ought to have seen that at no point in time would conditions be ideal or the particular arrangement without flaw. In any case, he accepted the verdict of the electorate and resolved to give confederation a fair trial.

For Anglin, as for the new Dominion of Canada, the years from 1867 to 1872 were a period of substantial adjustment. He ceased active opposition to confederation, though he certainly took pleasure in pointing out the deficiencies in its operation that he had predicted. In the first general election for the House of Commons he ran successfully in the predominantly Acadian Catholic constituency of Gloucester, on the North Shore of New Brunswick, a constituency he continued to represent for 15 years. In the country at large, he contested the unofficial leadership of Irish Catholics with Thomas D’Arcy McGee* until McGee’s assassination in April 1868. Thereafter, Anglin continued to speak out on issues of particular concern to this group but his criticisms were seldom vociferous. While he thought the condition of Irish Catholics in Canada far from perfect, he believed it was improving and at least was better than in the United States. As for New Brunswick’s position in the new political order, Anglin noted the problems, especially the difficult economic position of Saint John, but he believed that these were inevitable and perhaps not as bad as he had anticipated. On more general issues he registered concern that the geographical expansion of the country was burdening it too heavily and that in the 1871 Treaty of Washington [see Sir John A. Macdonald] Canadian rights had been sacrificed. In these and other matters, however, Anglin demonstrated his acceptance of the new dominion by evaluating them on the basis of what he judged to be the best interest of the nation. He also found a more established party position in the House of Commons, gravitating from sitting as an independent in 1867 to being a prominent member of the loosely bound Liberal party under Alexander Mackenzie in 1872. Thus, during the country’s first five years the former anti-confederate came to terms with the new regime. He did not like all aspects of it, but he had given it a chance to prove itself and had not found it entirely wanting.

During 1872 and 1873 the issue that most involved Anglin was the New Brunswick schools question [see John Costigan*]. He considered that a New Brunswick act of 1871 relating to common schools made it impossible for Catholics to have their own educational institutions unless they were willing to pay for them above and beyond public school taxes, an arrangement contrary to practices that had existed at the time of confederation. It was an intricate question and Anglin championed the Catholic case in many arenas: in the pages of the Freeman; behind the scenes in Ottawa and on the floor of the House of Commons; in consulting with, seeking direction from, and proffering advice to the province’s Catholic bishops, John Sweeney* and James Rogers*; and in assisting in the preparation of submissions to the courts that heard cases challenging the legislation. New Brunswick’s Catholics were ultimately unsuccessful, but Anglin’s strenuous efforts on the schools question did not endear him to the Protestant politicians in the province. Thus when Macdonald’s government fell as a result of the Pacific Scandal in November 1873, Anglin was excluded from the new administration formed by Alexander Mackenzie, in spite of his acknowledged prominence in Liberal circles. The other New Brunswick members claimed that the people of the province would not support a cabinet of which Anglin was a member. As a reward for his valued services to the party Anglin was named speaker of the House of Commons in March 1874.

As speaker, Anglin overcame his disputatious nature, applied his undoubted industriousness and intelligence to the job, and fulfilled his functions adequately. Of course, he was unable to participate in the ongoing debate in the house on the schools question, although he continued to work quietly behind the scenes in Ottawa and voiced his views quite openly in the Freeman. Indeed, being both speaker and newspaperman proved to be a problem. It was difficult to maintain an aura of impartiality in his handling of the house while publicly expressing partisan views in his newspaper. Moreover, the connection between the government and the Freeman got Anglin into serious trouble for conflict of interest, which resulted in his being unseated from the commons in 1877. Although he had followed previous practice and had endeavoured to keep the business side of the Freeman at arm’s length, the commons committee which eventually heard the case proclaimed that earlier precedent and practice were erroneous and that the printing orders the Freeman’s business office had received from the Post Office Department in 1874 and 1875 constituted disqualifying contracts. This report was withheld until the end of the session in April, thus allowing Anglin to fight a bitter summer by-election and be re-elected speaker at the beginning of the 1878 session, though not without a divided vote.

During the 1870s Anglin’s basically conservative outlook became evident. Along with numerous others, he feared and denounced socialism, red republicanism, and communism as threats to western civilization, especially its religious foundation. He shared the view of many Catholic leaders that the church and Christian morality were endangered by atheism and scientism. Being frightened about these and other disturbing trends, Anglin rejected any attempt to weaken further the role of religion in society. He claimed that clergymen had a right and a duty to identify and condemn what was unlawful and sinful. Equally, however, the Catholic was as much at liberty as anyone else to judge political questions for himself. To the Quebec clergy who denounced the Liberal party [see Ignace Bourget*], he replied that it was not the same as “the infidel party who in Europe disgrace the name of Liberal by warring bitterly against all true liberty, against society and against God.” Although a Liberal, Anglin was no social reformer. As a puritanical moralist he was unsympathetic to the foibles of human nature. He supported worthy charities but he placed great emphasis on the maintenance of law and order. He believed in the power of religion and hard work to overcome what he considered to be the limited amount of poverty in North America. Yet despite his conservatism and his commitment to free enterprise, he did not join the many middle-class Canadians who condemned workers’ organizations. Indeed, he gave the activities of such groups reasonably objective coverage in the Freeman. Anglin even came to sympathize with efforts of labour unions, many of whose members in Saint John were Irish Catholics, to improve their position, provided their actions were legal, moderate, and non-violent.

Following the defeat of the Liberals in 1878 Anglin’s political fortunes went into decline. He was a key critic of the Macdonald government between 1878 and 1882 both on the floor of the commons and in the Freeman, particularly on the major issues of the day, the National Policy and the Canadian Pacific Railway. He continued to speak on issues of concern to Irish Catholics, including support for economic aid and Home Rule for Ireland. But his political base in Gloucester was weakening, undermined by the rise of Acadian nationalism [see Onésiphore Turgeon*], the disinclination of Bishop James Rogers to provide continued support, the ascent of ambitious local politicians, and his own failure to maintain strong contacts in his constituency. He waged a courageous campaign in the 1882 election but was ignominiously defeated by Kennedy Francis Burns. This disaster, along with the declining fortunes of his newspaper, led Anglin to sever his tie with the Freeman and move to Toronto in 1883.

In Saint John life had come to seem dull, unfulfilling, and unpromising. The attraction of Toronto was that he was expected to play a central role in Liberal leader Edward Blake*’s strategy of wooing Ontario Catholics to the federal party. With financial support from party members he took over the Tribune, a Catholic weekly. In addition he became an editorial contributor to the Globe. It was also expected that the Liberals would try to find a commons seat for him. Anglin worked hard at these various activities, even undertaking the hopeless task of running against D’Alton McCarthy in Simcoe North in 1887, but his diligence paid few dividends for the Liberals, and after their defeat in the 1887 election they withdrew their support. The Tribune went under and Anglin lost his position at the Globe. These disillusioning experiences also brought a lack of employment that caused him considerable anxiety, for at 65 he had a wife and seven children aged 4 to 22 to support. The Anglins were never destitute, since he had managed in earlier years to put aside a substantial investment, but he did not again find steady work until just prior to his death.

In the mean time Anglin managed to secure several patronage appointments from Oliver Mowat*’s Ontario Liberal government: chairman of the Commission on Municipal Institutions, which made two reports in 1888; commissioner in charge of Ontario’s mineral display at the 1888 Centennial Exposition of the Ohio Valley; secretary in 1890–91 to the Commission Appointed to Enquire into the Prison and Reformatory System of Ontario; and member of the Ontario Royal Commission on Municipal Taxation, which reported in 1893. But the problem of sporadic employment got so bad that his wife and his eldest son, Francis Alexander*, were reduced to making secret and unavailing appeals to his political opponents Sir John A. Macdonald and Sir John Sparrow David Thompson, begging them to give Anglin a federal appointment. During these years he also wrote a few articles for journals and newspapers, made the occasional speech, wrote the chapter on Archbishop John Joseph Lynch* in a volume celebrating the 50th anniversary of the archdiocese of Toronto, and was a trustee on the Toronto Separate School Board from 1888 to 1892. Not until May 1895 did he obtain steady employment, as chief clerk of the Surrogate Court of Ontario, the influence of his two lawyer sons, Francis and Arthur Whyte, probably being a factor in the appointment. A year later he died of a blood clot on the brain.

Anglin was not a front-ranking personage in Canadian history, but he was in no way a failure. He had been diligent and competent in almost all his endeavours – as newspaperman, as politician, as Irish Catholic spokesman, as speaker of the House of Commons, as commissioner. He had not risen to heights of brilliance, but he was a man respected for his capabilities, determination, conscientiousness, and uprightness. During the second half of the 19th century his name was known and his words read or heard throughout much of British North America. As a leader of Irish Catholics, he had provided an important mechanism for accommodating that group within Canadian society. Finally, despite the anxiety of his later years, he had provided a firm foundation for the careers of his children. Francis rose to be chief justice of the Supreme Court of Canada and Mary Margaret became an internationally renowned actress. Anglin was not a particularly engaging individual, and was frequently guilty of dogmatism and self-righteousness, but in the final analysis his character and career command respect and admiration.

[This article is essentially drawn from my biography, Timothy Warren Anglin, 1822–96: Irish Catholic Canadian (Toronto and Buffalo, N.Y., 1977). The main sources on Anglin are cited in the footnotes of that work and few new materials have come to light since its publication. The most significant single source is the Freeman. It began in 1849 as the Saint John Weekly Freeman (Saint John, N.B.); on 4 Feb. 1851 it became a tri-weekly, the Morning Freeman; from 29 Aug. 1877 to 2 Nov. 1878 it was a daily; thereafter it reverted to being a weekly publication. Also of use are the Tribune (Toronto), 1883–87, other contemporary newspapers, and the private papers of numerous individuals such as John Sweeney (Arch. of the Diocese of Saint John), Sir Samuel Leonard Tilley (NA, MG 27, I, D15, and N.B. Museum, Tilley family papers), Edward Blake (AO, MU 136–273), Arthur Hill Gillmor* (PANB, MC 243), Alexander Mackenzie (NA, MG 26, B), and James Rogers (Arch. of the Diocese of Bathurst, N.B.; copies at UNBL). w.m.b.]

Cite This Article

William M. Baker, “ANGLIN, TIMOTHY WARREN,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 12, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed February 21, 2026, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/anglin_timothy_warren_12E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/anglin_timothy_warren_12E.html |

| Author of Article: | William M. Baker |

| Title of Article: | ANGLIN, TIMOTHY WARREN |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 12 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1990 |

| Year of revision: | 1990 |

| Access Date: | February 21, 2026 |