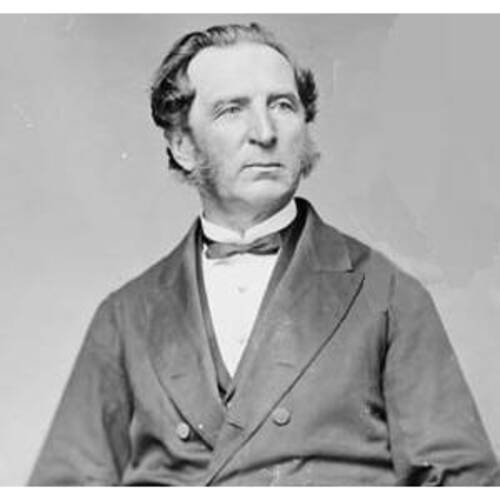

Source: Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

FISHER, CHARLES, lawyer, politician, and judge; b. 15 Aug. or 16 Sept. 1808 at Fredericton, N.B., eldest son of Peter Fisher and Susanna Williams; d. 8 Dec. 1880 at Fredericton.

Peter Fisher, a merchant and lumber operator of loyalist ancestry, is noted for his Sketches of New Brunswick (1825), the first historical study published in the province. More a description than a history, the book was highly critical of those big businessmen who exploited the province while contributing nothing to its progress. Charles Fisher seems to have been influenced by his father’s point of view on this subject.

Charles Fisher was educated at the Fredericton Collegiate School and at King’s College (University of New Brunswick), where he received a ba in 1830. He turned to the study of law under the attorney general, George Frederick Street*, was admitted attorney to the New Brunswick bar in 1831 and, after a stay at one of the Inns of Court in England, became a barrister in 1833. He started his practice in Fredericton where, in September 1836, he married Amelia Hatfield, by whom he had four sons and four daughters.

Almost as soon as he was admitted to the bar, Fisher turned to politics, running unsuccessfully for York County in the 1834 election. Three years later he entered the assembly as a colleague of Lemuel Allan Wilmot, also from York. For the next 10 or 12 years these two were the backbone of the New Brunswick reform movement, working mainly for responsible government. Wilmot has gone into the history books as the great man in the movement, but Joseph W. Lawrence*, an acute contemporary observer, quotes with approval the widely held view that “Fisher made the balls and Wilmot fired them.” Fisher certainly understood the issues behind the constitutional changes being demanded, and may well have worked out the arguments which the more volatile Wilmot presented.

Following his election in 1837, Fisher worked diligently, often in cooperation with the government. A moderate reformer, he attempted to effect innovations in the fluid non-party structure of the day. New Brunswick was governed, often well but frequently injudiciously, by the lieutenant governor and the executive councillors, none of whom had a seat in the assembly in the 1830s. Not content to exist in what he considered an imperfect system, Fisher demanded improvements. In 1842 he introduced a bill requiring that assemblymen resign and seek re-election when appointed to the Executive Council or to an office with remuneration. He introduced another resolution calling for the initiation of money bills by the executive – an essential practice for efficient government; it was defeated 23 to 12, apparently because the members were not yet ready for such a sacrifice. Fisher also pressed for bills to fix the property qualification of legislative councillors at £500, to reduce the charges on the province under the civil list bill, to limit the salaries of department heads to £600, and to have all fees placed in the public treasury, not in the pockets of office-holders. His reform proposals reveal a deep streak of parsimony.

During the 1840s Fisher’s relationship with Edward Barron Chandler and Robert Leonard Hazen, the leaders of the government, was most amicable: They appointed him registrar at King’s College in 1846 knowing full well that the move was probably “distasteful” to the college council. Fisher wrote to his friend Joseph Howe on the evil ways of the “family compact” and on the irresponsible nature of the government and its politics. “Till this Election,” he wrote in 1843, “I could not believe that respectable people would resort to such lies as have been made use of in this community to carry a point & the acrimony they evince exceeds anything to be conceived.” At the same time Fisher hoped to avoid party strife in the small province of New Brunswick even though he praised it elsewhere. In one breath he could exult in “the general liberal triumph” of 1847 in Nova Scotia. In another: “He would regret to see the day when the organization of violent antagonistic political parties would be found necessary in this province” where “there was little talent enough for one good Government.”

Fisher divorced the concept of responsible government from party considerations. He wrote of New Brunswick: “We are too loyal and too ignorant to put down the old [compact].” The best approach was a coalition which “with the growing influence of the liberals would in ten years give the liberals all without any violent movement.” It was with this point of view that Fisher, fully aware of the theoretical ramifications of responsible government, moved his resolution of 1848 “that the House should approve of the principle of Colonial Government contained in the despatch of the Right Honorable Earl Grey [Henry George Grey] . . . and of their application to this province.” The motion was carried 24 to 11 and within three months Fisher entered the government formed by the new lieutenant governor, Sir Edmund Walker Head*. For taking this step both Fisher and L. A. Wilmot, who was appointed attorney general, have been accused of desertion and lack of principles. Fisher’s defeat in the election of 1850 is offered as proof of public indignation. If the partisanship of the party system was required to attain responsible government, for which Fisher had been chief advocate and theoretician, then he had committed an indefensible act. If it could be achieved by coalition and collaboration without loss of integrity, then Fisher was wrongly accused. In his own defence he said: “In accepting office, I have compromised no principles; I have neither changed nor surrendered any opinion which I have heretofore advocated in Trade [in particular] nor Politics in general.”

Fisher was not prominent in the council: Hazen, Chandler, John R. Partelow*, and even Wilmot tended to dominate. He wrote to Howe asking him about the operation of the council. “Does the Governor take the opinion of the whole Council and act upon the recommendation of a majority?” Fisher thought the appointment of persons to the Legislative Council was “a Branch of patronage indispensable to the well working of an Executive Council” and that the decision of that council must prevail. Lieutenant Governor Head, however, was not a man who would be ruled by his council.

Fisher’s defeat in the election of 1850 should have been followed by his resignation as a matter of course, but he stayed in the council until January 1851. Governor Head had just before this date appointed a new chief justice, James Carter, and had filled the vacancy on the Supreme Court with L. A. Wilmot. Both appointments were made in spite of the advice of the Executive Council. Fisher resigned, he stated, because the governor had not acted “consistent with my ideas of Responsible Government.” Since his resignation was overdue, the sentiment has a hollow ring, yet Fisher realized better than anyone that Head had crippled responsible government for the time being. Its resurrection became his goal. By this time Fisher had lost faith in a coalition system; from being an opponent of the party system, he became its champion, and set about to weld together a party that would gain power and control all aspects of government, especially the actions of the governor.

Fisher’s status as a constitutional lawyer and the respect he enjoyed from the “compact” council resulted in his serving, from 1852 to 1854, with William B. Kinnear* and James Watson Chandler* on a commission appointed to consolidate and codify the provincial statutes and to examine the courts of law and equity and the law of evidence. The results of the study were published in many volumes in 1854.

The year 1854 was an election year in New Brunswick and Fisher returned to the house. There was a new lieutenant governor, John Henry Thomas Manners-Sutton, and reciprocity with the United States provided a new political issue. When the house was called together to ratify the reciprocity treaty in the fall of 1854, Fisher, fully aware that he controlled a majority in the house, rose on 20 October to introduce an amendment to the fifth paragraph of the address in reply to the speech from the throne. He stated “that your Constitutional Advisers have not conducted the Government of the Province in the true spirit of our Colonial Constitution.” Should the governor believe, declared Fisher, “that the Bluenoses had no pluck, that the New Members were divided and split into sections with internal jealousies and disputes, and could be easily beaten in detail . . . , it was only fair to disabuse his mind.” The amendment was carried on 28 October by a vote of 27 to 12, and Fisher was called upon to form a government. The compact council was finally removed from office; responsible government had been rescued by the creation of a political party.

Fisher, who became attorney general, proceeded to form a government that ranks with the best in the history of the province. Young and talented, it included men of such future prominence as Samuel Leonard Tilley*, Albert James Smith*, William Johnstone Ritchie*, John Mercer Johnson*, James Brown*, and William Henry Steeves. When the extensive legislative record that followed is considered, the old saw that New Brunswickers were unfit for responsible government before 1854 may well deserve retirement. The new council contained no member of the historic families, and represented, for the most part, the middle class. Levelling, anti-establishment, commercially oriented, the new government meant a “social as well as political” change.

Fisher immediately set about his programme of reform. First the Legislative Council, formerly the preserve of the establishment, was shorn of its power. Its president was included in the Executive Council, and thereby lost his independence. About the same time the bishop of the Church of England was induced to give up his seat in the upper house. Of greater importance than these changes was the “Reform Bill of 1855,” calling for “an extension of the franchise . . . to secure the fair representation of intelligence and property at the Polling booths.” Fisher pressed for the removal of the £25 property qualification, but, not a supporter of universal manhood suffrage, he wanted to retain the requirement that each voter have a yearly income of £100. Vote by ballot was also introduced. The Liberal party, Fisher maintained, would always be “practical . . . progressive . . . conservative of everything good . . . destructive of everything evil in the political and social condition of the people of this country.” With this aim in mind an act was later presented to prevent any person who conducted business with the government from being elected to the assembly or holding a seat in the upper house.

Sound financing had always been one of Fisher’s themes, and, in 1856, the government supported a private member’s bill to the effect that “the right of initiating money grants should be conceded to the Executive government and the practice of the imperial parliament in this respect adopted.” A new department of public works was created to carry out government projects, especially the building of highways and railways. New municipal institutions were set up, to “train men in the principles of self-government.” Other reforms sought to limit the interest rate to 6 per cent, to introduce decimal currency, to regulate the qualifications of members of the medical profession, and to simplify legal procedures. Fisher supported a public school system but he was unable to push it through; he did establish an improved teacher training system, and named his brother, Henry Fisher, chief superintendent of education for the province.

Two pieces of legislation – the Prohibition Act and the University of New Brunswick Act – require some elaboration. S. L. Tilley, Fisher’s provincial secretary, introduced a private member’s bill on 3 March 1855 to prohibit the manufacture and sale of alcoholic beverages after 1 Jan. 1856. Passed by a vote of 21 to 18, it received royal assent, and the members of the government, although divided on the issue, became responsible for upholding the act. The law was not and apparently could not be enforced, and the public outcry for repeal was so great that Manners-Sutton seized on the issue as a way to escape from the Fisher government, which he did not like. When it refused to repeal the law, he forced its resignation, and in the ensuing election had the pleasure of seeing his unconstitutional methods justified. The John Hamilton Gray*–Robert Duncan Wilmot* government received a majority and repealed the law (1856). Within a year, however, Fisher was back in power. With the prohibition issue out of the way it became clear that Fisher and his supporters were more in tune with New Brunswickers than Manners-Sutton’s carefully chosen men.

King’s College was another contentious issue. People like A. J. Smith and Charles Connell repeatedly pressed for its abolition on the grounds that it was a plaything for the privileged subsidized by yeoman labour. Fisher, as a graduate and long time registrar, defended the college but in 1858 he could not stop a bill to abolish it. British disallowance of the act and the inclusion of Connell in the Executive Council as postmaster general brought the college issue up for reconsideration, and in 1860 the University of New Brunswick Act became law. Fisher’s bill, based on a commission report, set up a non-sectarian university with a much broader curriculum than in the old classical college.

During these years Fisher was actively supporting railway construction. Though once burned in effigy in Saint John for opposing the Saint John to Shediac line, he was a solid supporter of the European and North American Railway as well as the Intercolonial. After consulting Joseph Howe, Fisher, accompanied by John Robertson, held discussions in London in 1855 on the Saint John to Shediac line, then partly finished. The line was taken over completely by the government. When the Intercolonial project was again revived in 1858, Fisher, full of hope, went to London only to see both the railway project and the union of British North America dismissed as impractical.

Despite some rebuffs Fisher appeared, as the 1860s dawned, to be in complete control of New Brunswick. His government was successful and popular. Tilley, the provincial secretary, was doing most of the administrative work and looking after the affairs of state in general. When he wrote to Fisher in 1859 about serious financial problems, Fisher replied “dont be disheartened. It will all turn out for the best. . . .” He let Tilley find solutions while he concerned himself with crown cases in the law courts of the province. As attorney general that was his responsibility, but it seems that he left far too much to Tilley. For reasons that are unclear, some members of the council, especially A. J. Smith, wanted to be rid of Fisher. Perhaps his leadership was not strong enough. Perhaps he looked too much to the needs of his family and of Fredericton rather than the province. Perhaps it was his personality. One contemporary remarked on Fisher’s “want of . . . frankness.” “Privately he was not always to be understood – there was a non-commitalism about him, even in important matters, which many of his friends could not account for, as though he always felt that his best counsellor was himself, and the least he divulged to others it would be all the safer for his side.” Whatever the reason, a tide began to swell against Fisher in 1858, and when he was implicated in a crown lands scandal of 1861, his colleagues dumped him immediately. Undeniably he used his position to exploit the crown lands for himself, his friends, and his relatives, yet he claimed he was taking the brunt of an attack which should have been more widely spread. He refused to admit a misdeed and he refused to resign as attorney general and thus “compromise his character and independence.” Tilley, who emerged as leader, eventually had Fisher removed from the council and induced him to resign as attorney general rather than face further humiliation.

Thus ended Fisher’s career as leader of the government. Its record was one of which he could be proud, for it covered constitutional, political, social, and economic reforms that were badly needed. The extent of Fisher’s success can be gauged by the complete disintegration of the old “compact” and of all party opposition.

Following his removal in 1861, Fisher remained in the House of Assembly and was easily re-elected in the general election later that year. His constituents apparently believed he had not been treated fairly as did long-time friends such as Joseph Howe and George E. Fenety*. Fisher’s personal following in the province and in the assembly posed a serious threat to Tilley. Certainly Tilley feared that Fisher might control the balance of power, and in February 1862 believed he faced an attempt to overthrow him, but this either failed or did not take place. For the next few years Fisher waited, looking forward, he claimed, “to uniting with Tilley” and to again becoming attorney general “at no distant day.” Little separated them for they agreed completely on railway policy, especially the Intercolonial. It was confederation that was to reunite them.

Tilley went to the Charlottetown meeting of 1864 on Maritime union expecting little. Fisher was opposed to a Maritime union but supported a British North American federation. The totally unexpected conclusion of the Charlottetown conference and Tilley’s commitment to confederation required remodeling of the Liberal party into a union movement, for the issue was so contentious that it required more support than Tilley had. Charles Fisher was therefore invited to join the New Brunswick delegation to the Quebec conference. His contribution does not seem to have been significant. He “preferred a legislative union if it were feasible,” but said little except to complain that Canadian domination was excessive and unwarranted. Whatever his apprehensions, he agreed with the over-all conclusions of the conference and returned to New Brunswick confident that the province would follow the lead of the delegates.

New Brunswick was the only province in which the Quebec scheme was voted on in an election. In March 1865 the Tilley government and the confederation project were overwhelmingly defeated. Tilley and Fisher suffered personal defeat and all but six of their supporters fell before the anti-confederation platform of their old colleague, A. J. Smith. Fisher had concentrated his efforts in York County; there as elsewhere the suspicions of New Brunswickers that confederation was a plot originated in “the oily brains of Canadian politicians” could not be allayed.

Charles Fisher’s role in reversing the decision of 1865 was central. The death of the chief justice, Robert Parker*, in November 1865 created a vacancy on the bench that was filled by John Campbell Allen*, mla for York County. A by-election was called immediately, and Charles Fisher offered: “The strong feeling evinced for me . . . leave[s] me no honourable alternative but to step into the arena and throw myself upon you, my fellow subjects.” It is unlikely that Fisher’s motives were entirely altruistic and it is true that he treated confederation as a minor issue in the campaign, but in the final analysis this by-election was a key to the success of the movement. Confederation desperately needed a boost in the fall of 1865, and a defeat might have discouraged the confederates into giving up. However from the moment of Fisher’s victory over John Pickard by a two-thirds majority until Smith’s resignation, forced upon him by an unconstitutional action of the lieutenant governor, Arthur H. Gordon*, the pressure in favour of confederation mounted steadily. Fisher’s part in Smith’s defeat centred on an amendment to the speech from the throne which he introduced on 12 March 1866 and which led to a four-week debate. The governor eventually forced Smith out of office, and Fisher became attorney general in the S. L. Tilley–Peter Mitchell* government that was to carry confederation. He had, as he predicted, returned to his position. It may be that he forestalled Smith’s move because he did not wish Smith to claim any rewards – the New Brunswick Reporter, a Fisher paper, said as much, and John A. Macdonald* certainly suspected it.

One of Fisher’s rewards was the voyage to England as a delegate to the London conference. There he was thought to be “a good fellow, who talks a good deal and has only a mediocre capacity.” Following the success of the London conference and the creation of the new nation, Fisher was one of the first to present himself as a candidate for election to the dominion parliament. He was unopposed. Fisher definitely entertained hopes of being included in Macdonald’s first cabinet; Tilley wanted him, but geographic considerations excluded two Saint John River men. After considerable hesitation Tilley selected Peter Mitchell as his fellow cabinet member. Fisher was left with much of the responsibility of reorganizing the New Brunswick government which had many problems caused by the mass exodus to Ottawa.

Because of his distinguished career and his Maritime origin, Fisher was selected to move the address in reply to the speech from the throne – the first speech in the new dominion parliament. That speech, which was received indifferently, marked the highlight of his federal career. As new tariffs and other policies were introduced, mostly over the objections of the New Brunswick members, Fisher recoiled into a defensive position. The selection of the north shore route for the Intercolonial was typical of the decisions he disliked: “If you prefer the longest, the most expensive and the least productive line, then by all means build the Northers; but do not flatter yourself with the belief that it will command much travel and traffic.” Defeated on this as on other issues, Fisher, for the first time, seems to have lost interest in politics. With the appointment of his old associate, L. A. Wilmot, as lieutenant governor of New Brunswick in 1868, he sought the vacated judgeship. He was appointed after Tilley warmly supported him in a strong memo to Macdonald in September 1868, “I consider Mr. Fishers claims superior to any other man in New BN except Mr [John Hamilton] Gray.” On 3 Oct. 1868 Fisher was appointed puisne judge of the Supreme Court of New Brunswick and on 14 October judge of the Court of Divorce and Matrimonial Causes.

As a judge Fisher was considered thorough and conscientious rather than profound. His devotion had been to politics more than to the law and the change of pace was extreme. Yet he was considered the leading constitutional lawyer of the day.

In his years as a judge Fisher found that most of the old bitterness of the early struggles disappeared, and he became a respected elder statesman. He and his wife Amelia were at the centre of Fredericton society and were especially active at the university which had awarded him a dcl in 1866 and which Fisher served as a member of the senate. Little is known of Mrs Fisher except that she was inarticulate. An apocryphal story is worth repeating because it may contain a germ of truth. On the occasion of Fisher’s elevation to the bench Mrs Fisher asked “You’ll be ‘Your Honour’ and what will I be?” He replied instantly, “You will be the same damned old fool you always were.” Fisher remained alert and active until the end. On Saturday, 5 Dec. 1880, he was well; on Tuesday, 8 December, he was dead, apparently from an inflammation of the lungs.

Of all those who participated in the struggle both for responsible government and for confederation, Fisher has received the least attention and has never had a biographer. Historians have been content to incriminate the “corrupt Charles Fisher” with his “bad reputation, deserved or not.” One statement is quoted widely as the final word on Fisher. The Duke of Newcastle [Henry Pelham Clinton] wrote: “I am not ignorant that Mr. Fisher is one of the worst public men in the British North American provinces and his riddance [1861] is a great gain to the cause of good government in New Brunswick.” This statement, the crown lands scandal, and his apparent willingness to disregard principles in 1848 seem to be the major reasons for the denigration of Fisher. His not entirely attractive personality may also have contributed.

A more favourable interpretation is reached if one considers Fisher’s attitude to parties on the one hand and the nature of colonial politics on the other. It seems clear that politics in New Brunswick differed little from politics in Nova Scotia or Canada. The “spoils” of office was an integral part of the system both in British North America and in Britain. Fisher got caught in the crown lands scandal, yet his exclusion from office was only temporary. His constituents and friends honestly believed he was treated unjustly, and S. L. Tilley, whose probity as a politician ranks as high as any, did not hesitate to recommend Fisher to the bench. Fisher’s reputation was set by the opinions of young, inexperienced, and frequently arrogant individuals of the British colonial system such as Manners-Sutton, Gordon, and the Duke of Newcastle. Their views of either the people or the society in the colonies can hardly be accepted as definitive. Fisher in particular refused to defer to these officers and was singled out for this reason. A gentleman, by their definition, he may not have been, but a close examination of his career leads to the conclusion that he was a better man than most. A few years before his death he stated what might well have been his obituary: “My object is not personal aggrandizement; and I do not regard the gathering together of money as important, except for the sake of my family. I want to live and to act so, that when I die men may say of me, ‘he left the impress of his mind on the institutions of his country.’”

[There is no Charles Fisher manuscript collection, but useful material is available in: N.B. Museum, Edward Barron Chandler papers; Tilley family papers. PAC, MG 24, B29 (Howe papers); MG 26, A (Macdonald papers); MG 27, I, D15 (Tilley papers). PRO, CO 188 (letters of Edmund Walker Head, John Henry Thomas Manners-Sutton, and Arthur Hamilton Gordon). University of New Brunswick Library, Archives and Special Collections Dept., Arthur Charles Hamilton Gordon papers, 1861–66.

Among the contemporary printed sources are: New Brunswick, House of Assembly, Journals, 1834–68; Synoptic reports of the proceedings, 1834–68. Globe (Saint John, N.B.), 1858–68. Morning News (Saint John, N.B.), 1839–65. New Brunswick Reporter (Fredericton), 1844–80. Saint John Daily Telegraph and Morning Journal, 1869–73. Saint John Morning Telegraph, 1862–68.

There is no biography of Fisher except for the short and inadequate ones in J. C. Dent, Canadian portrait gallery, IV, and Biographical review, this volume contains biographical sketches of the leading citizens of the province of New Brunswick, ed. I. A. Jack (Boston, 1900). Other sources include: G. E. Fenety, Political notes and observations, and his “Political notes,” Progress (Saint John, N.B.), 1894, collected in scrapbooks in N.B. Museum and PAC.

Lawrence, Judges of New Brunswick (Stockton) is of some use for information on Fisher as is Hannay, History of New Brunswick, II. The latter has been largely superseded by MacNutt, New Brunswick: a history. D. G. G. Kerr, Sir Edmund Head, a scholarly governor, with the assistance of J. A. Gibson (Toronto, 1954) should be consulted along with J. K. Chapman, The career of Arthur Hamilton Gordon, first Lord Stanmore, 1829–1912 (Toronto, 1964). See also the following articles: A. G. Bailey, “The basis and persistence of opposition to confederation in New Brunswick,” CHR, XXIII (1942), 374–97. J. K. Chapman, “The mid-nineteenth-century temperance movement in New Brunswick and Maine,” CHR, XXXV (1954), 43–60. W. S. MacNutt, “The coming of responsible government to New Brunswick,” CHR, XXXIII (1952), 111–28.

By far the most valuable study of Fisher is E. D. Ross, “The government of Charles Fisher of New Brunswick, 1854–1861,” unpublished ma thesis, University of New Brunswick, 1954. c.m.w.]

Cite This Article

C. M. Wallace, “FISHER, CHARLES,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 10, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed February 21, 2026, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/fisher_charles_10E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/fisher_charles_10E.html |

| Author of Article: | C. M. Wallace |

| Title of Article: | FISHER, CHARLES |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 10 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1972 |

| Year of revision: | 1972 |

| Access Date: | February 21, 2026 |