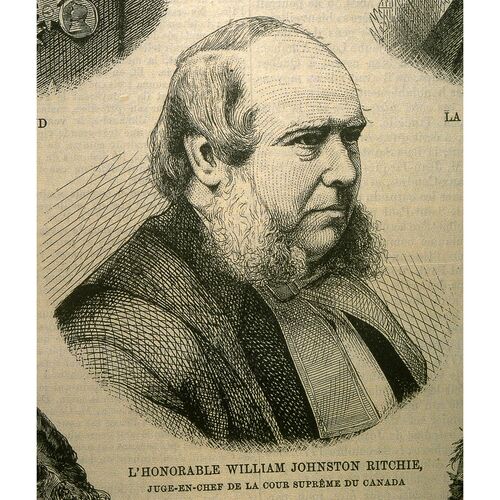

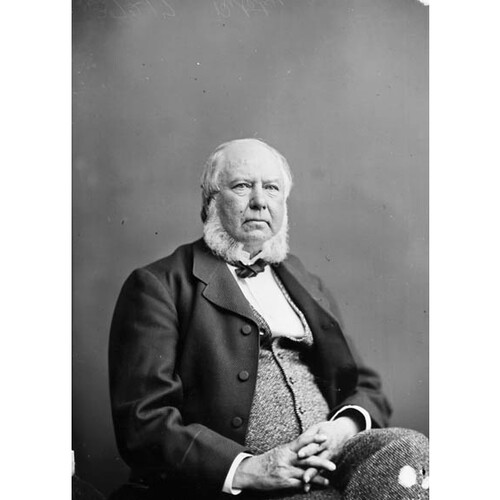

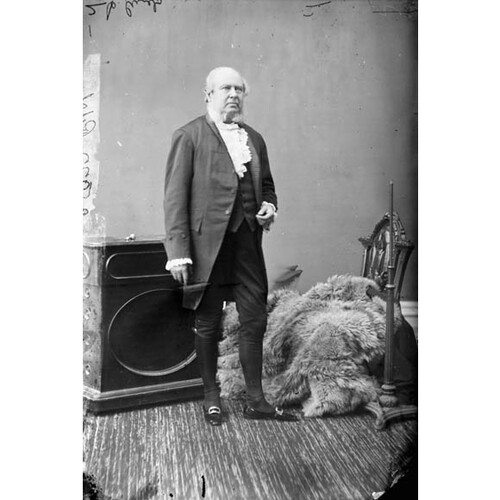

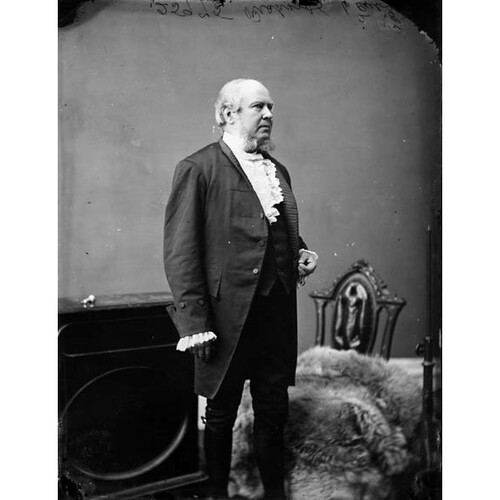

RITCHIE, Sir WILLIAM JOHNSTON, lawyer, politician, and judge; b. 28 Oct. 1813 in Annapolis Royal, N.S., third son of Thomas Ritchie* and Elizabeth Wildman Johnston; d. 25 Sept. 1892 in Ottawa.

William Johnston Ritchie’s father was a member of the House of Assembly for Nova Scotia who later became a judge of the Inferior Court of Common Pleas for the western division of the province. His mother was a daughter of William Martin Johnston and Elizabeth Lichtenstein*. She died when he was less than six years of age, leaving a family of five boys and two girls. Thomas Ritchie remarried twice and had two children from his third marriage. Little is known about the young William Ritchie but some 60 years later “grey-beard inhabitants” of Annapolis remembered him as a “rollicking, rosy-cheeked, bright-eyed boy, full of fun and animal spirits.”

Ritchie was educated at the Pictou Academy under Thomas McCulloch*, a Presbyterian minister and founder of the first non-sectarian school for higher education in Nova Scotia. McCulloch was an outstanding educator who subsequently became the first president of Dalhousie College in Halifax and it may be assumed that the young Ritchie received a sound and thorough education. He chose to study law in Halifax with his elder brother John William Ritchie*, who would later serve as a judge of the Nova Scotia Supreme Court.

Although William Ritchie was called to the Nova Scotia bar in 1837, he moved to New Brunswick and was admitted to practise law in that province in 1838. It is unclear why he chose to leave Nova Scotia. His early practice in Saint John was not lucrative: he recalled that he handled one case in his first year and that his professional earnings the next year were only £5. Ritchie became much more successful in the early 1840s, however; according to a contemporary, Joseph Wilson Lawrence, he “built up the most extensive and lucrative practice, probably, that any one has enjoyed in the City of St. John.” He developed a reputation for integrity and sound judgement in his legal business, and the energy with which he promoted his clients’ interests contributed to his success with judges and jurors. His forceful advocacy led to his being challenged to a duel on 19 Aug. 1845 by Edward Lutwyche Jarvis, whose father was being sued by Ritchie’s client. Jarvis accused Ritchie of insinuating fraudulent conduct on his part. In a letter to his challenger, Ritchie rejected the notion that he might have wronged him, and said that he had acted honourably, making no statements “but such as the evidence, the just development of the rights of my client, and the ends of justice warranted.” “I shall never,” he concluded, “allow myself to be overawed or deterred from fearlessly doing my duty to my clients, please or displease whom it may.” It was a sentiment he claimed to be guided by, both before and on the bench. Ritchie’s decision neither to apologize nor to fight a duel was taken with the concurrence of his legal peers and marks a salutary and significant change in gentlemanly conduct from that of 1821 when George Ludlow Wetmore* was killed by George Frederick Street* in a duel near Fredericton.

On 21 Sept. 1843 Ritchie had married Martha Strang at Rothesay, Scotland. She was a daughter of the late John Strang, a leading St Andrews shipping merchant. This marriage produced a son and a daughter. Martha died in 1847 and on 5 May 1856, in Saint John, Ritchie married Grace Vernon Nicholson, a daughter of the late Thomas L. Nicholson and stepdaughter of Vice-Admiral William Fitz William Owen*. They would have twelve children, seven sons and five daughters.

Despite his lucrative practice, Ritchie did not devote all his energies to the law. He also took an interest in politics. George Edward Fenety, a journalist and keen observer of the New Brunswick political scene, noted that “Mr. Ritchie was brought up in an ultra Tory camp, yet he had sufficient independence of character, when he crossed the Bay and had made himself conversant with the political situation in this Province, to cast in his lot with the advocates of reform.” Whether he shed the strong tory views of his family because of his education at Pictou or because he found himself initially outside the circles of privilege in New Brunswick is uncertain. Whatever the case, in taking up the reform banner Ritchie became a staunch advocate of responsible government.

He first ran for a seat in Saint John County and City in 1842. Although unsuccessful, he was observed by Fenety to be “a young Liberal of great determination, just beginning to show fire.” The province’s government was then based on a mixture of British colonial and New England ideas that had been imported by loyalists after the American revolution. When the province took over the administration of crown lands in 1837 [see Thomas Baillie*], it obtained exclusive control over all internal sources of provincial revenue. The House of Assembly dispensed these revenues according to the local concerns of individual members, with little leadership from an executive that lacked the leverage to initiate policy for the good of New Brunswick as a whole. Responsible government held scant attraction for assemblymen because it would limit their powers of appropriation. Thus in 1842, when Ritchie was first a candidate, the popular mood was not one of reform, although a notable advocate of the “radical” idea of responsible government, Lemuel Allan Wilmot*, was elected for York County. That Wilmot was chosen to sit on Lieutenant Governor Sir William MacBean George Colebrooke*’s Executive Council in 1843 with conservative members of the provincial “family compact” such as Robert Leonard Hazen* and Edward Barron Chandler* reveals how far from the British notion of party government New Brunswick remained.

When Ritchie ran, successfully, for Saint John County and City in 1846, responsible government was very much an issue. He claimed in 1847 that with his first candidacy in 1842 he had advocated not only a government based on the confidence of the assembly, but also an executive with the power to initiate money bills, “and he had seen nothing since to induce him to alter his opinion.” Together with Wilmot and with others who argued more or less strongly under the banner of reform, he continued to attack the ruling establishment. The reformers were labelled by Hazen “as rabid a set of men as ever any Government had to deal with.” In early 1848 the New Brunswick assembly considered Colonial Secretary Earl Grey’s dispatch of 31 March 1847 to the lieutenant governor of Nova Scotia, Sir John Harvey*, on the subject of instituting responsible government and passed a resolution to “approve of the principles of Colonial Government contained in the Despatch . . . and of their application to this Province.” Yet while responsible government had arrived in principle, its practice was still questionable. Surrender of the initiation of money grants to the executive also remained an unsettled issue.

For reform to happen some semblance of a disciplined party system was necessary. Despite the loose application of the terms Liberal and Conservative, most members of the assembly were guided by their local concerns and, above all, by the desire to retain a seat. The events of 1848 would show how easily party lines were crossed. That year the new lieutenant governor, Sir Edmund Walker Head*, invited longtime reformers Wilmot and Charles Fisher* into a government dominated by their former opponents. Their acceptance dismayed the “purist” Liberals such as Ritchie, who violently resented their actions, and did much to weaken the reform cause. As for the new government, according to historian William Stewart MacNutt*, the “only consistent opposition that faced it came from Ritchie and two or three other members who on occasion referred to themselves as ‘the Liberal party.’”

While the establishment of responsible government was being slowly and imperfectly realized, Ritchie was occupied with other legislative concerns. One cause for which he consistently agitated was the removal of the seat of government from Fredericton to Saint John, a proposal that had divided the colony for years and had prevented the construction of permanent government buildings. In a March 1848 attempt, the resolution was soundly defeated in the assembly.

Ritchie’s legislative record reflects a progressive, development-oriented approach to New Brunswick and its economy. He favoured inducements to immigration and settlement, and in 1847 advocated that 50-acre land grants be given to “hardy pioneers” from the United Kingdom, who would have the right to purchase up to 100 acres more after settling. Progress, Ritchie believed, depended on the enterprise of the individual farmer and the small businessman. Opposing a bill to repeal the usury laws, which limited lending rates to six per cent, Ritchie argued that such legislation would “place the whole resources of the country into the hands of some half a dozen money lenders.” His reform stance was aimed at freeing New Brunswick and its government from the few families that controlled its offices and purse.

Ritchie was also actively involved in the struggle to build railways in New Brunswick. There were two main proposals: an intercolonial line, which was to link Nova Scotia with the Canadas, and a line from Saint John to Shediac, later the route of the European and North American Railway, which would link up with American routes [see Edward Barron Chandler]. Ritchie strongly favoured the latter road, pushing for government support both as a member of the assembly and as a prominent member of the Rail-Way League. His agitation for this railway greatly increased his political stock in Saint John, but by 1850 the government had not approved any guarantees for it.

Ritchie’s status as perhaps the most committed of the New Brunswick reformers became apparent in 1851, when on 2 August, in Fenety’s words, “a terrible bomb-shell was thrown into the Liberal wigwam in St. John.” Robert Duncan Wilmot and John Hamilton Gray*, two Liberal members, moved over to join the tory government. Ritchie, Samuel Leonard Tilley, Charles Simonds*, and William Hayden Needham* harshly condemned the actions of their former colleagues, vowing that if Wilmot was re-elected after being appointed surveyor general, they would resign their own seats in protest. Wilmot was convincingly returned in Saint John. Ritchie, Tilley, and Simonds honoured their promises, earning themselves points for integrity but leaving the government with virtually no opposition for three years.

During his absence from the legislature, Ritchie continued his legal practice. His most significant client was the European and North American Railway, for which line he had lobbied so strenuously in the assembly. By late 1853 construction on the road was under way, Ritchie having drafted the contract with the British builders. He continued as counsel even after returning to the assembly in the 1854 elections. Before that vote, Ritchie was offered the honour of being appointed a qc. He accepted it only after being assured that it was offered, as Sir Edmund Head wrote, “without reference to party or political consideration of any kind.”

In June 1854 Ritchie won Saint John County and City by six votes; it was, however, widely believed by the opposition that his margin was only one vote. The ensuing session was most notable for the resignation of the government on 28 October. Charles Fisher, who had returned to the reform camp, brought forward a motion expressing a want of confidence in the tory administration and the resolution was adopted by 27 votes to 12. The executive resigned and Lieutenant Governor John Henry Thomas Manners-Sutton* called on Fisher to form a government. Responsible government had arrived in practice as well as in principle.

The early accomplishments of the new, ostensibly Liberal, administration – of which Ritchie was a member without office – included vesting the initiation of money bills in the executive and an election bill that introduced the secret ballot and extended the franchise. Ritchie strongly supported the electoral proposals, speaking for two and a half hours on their behalf during the debates. In 1855 S. L. Tilley introduced a prohibition bill. Ritchie voted to postpone consideration of this legislation but the bill passed and went into effect on 1 Jan. 1856. Its impact led to the Liberals’ electoral defeat later that year. By then, however, Ritchie was no longer a member of the government. On 17 Aug. 1855 he had been appointed a puisne judge of the Supreme Court of New Brunswick.

Ritchie’s appointment to the bench was accompanied by both praise and protest. Liberal supporters noted that as a barrister he had “gained an eminence rarely attained, while his long and diligent struggle for the establishment of Liberal principles in this Province must have an important influence in securing a just reward for such meritorious service.” There was also regret at the loss of his political talent and influence. Opponents questioned the appointment, claiming to have searched in vain for achievements that marked Ritchie as either a great statesman or a great lawyer. It was speculated that Attorney General Fisher had guaranteed the post to Ritchie to obtain support for his leadership of the new government in 1854.

One of Ritchie’s most notable decisions while on the New Brunswick bench arose out of the Chesapeake incident. In December 1863, during the American Civil War, a group of conspirators had captured a Union merchant ship, the Chesapeake, in the name of the Confederacy. The incident increased tensions between the United States and British North America since Union warships in recapturing the Chesapeake had violated imperial waters. Northerners viewed much of British North America as sympathetic to the Confederate cause and were threatening to scrap the reciprocity agreement of 1854. While diplomacy eased the difficulty to a large extent, Ritchie was faced with a decision whether or not to uphold a warrant detaining for extradition on piracy charges three conspirators – all British subjects – who had escaped to New Brunswick. Ritchie held that the warrant was improper and released the three because the act of piracy had not occurred within the territorial waters of the United States. The decision was hailed by some observers as the best solution to a difficult problem in that it spared the United States the necessity of prosecuting British subjects on charges carrying the death penalty. Ritchie had also avoided recognizing the belligerent status claimed by the accused, a recognition that would have inflamed opinion in the northern states. The captives’ release satisfied the Saint John populace, some of whom harboured sympathy for the Confederate cause. Ritchie maintained that he was not affected by such considerations: “Whomsoever it may please or displease must be to me, judicially, a matter of indifference. The only duty I have to discharge is . . . to declare the Law as I believe it to be, wholly regardless of consequences.”

Ritchie became chief justice of New Brunswick on 30 Nov. 1865, succeeding Robert Parker*. He was appointed over the head of the longer-serving and still popular Lemuel Allan Wilmot, who had become a puisne judge in 1851. Opponents of Albert James Smith*’s anti-confederation government called the supersession of Wilmot an “outrage,” arguing that the “insult to the senior judge appears gross, flagrant and without excuse.” Ritchie’s supporters claimed that Wilmot had used the bench as a political forum for his “harangues” promoting confederation, and that the government could not overlook such shocking behaviour. The controversy focused more on the insult to Wilmot than on Ritchie’s qualifications for the position.

In 1869 Chief Justice Ritchie wrote a decision, virtually forgotten today, which for the first time held a provincial statute to be invalid under the British North America Act of 1867. In The Queen v. Chandler Ritchie maintained that a New Brunswick debtor law of 1868 infringed on the exclusive power of the federal government to legislate in the area of bankruptcy and insolvency. Where parliament or the provincial governments “legislate beyond their powers . . . ,” he wrote, “their enactments are no more binding than rules or regulations promulgated by any other unauthorized body.” The case has been rightly compared to Marbury v. Madison, which in 1803 established the concept of judicial review of constitutional validity in the United States. Ritchie’s decision in Chandler merits an important place in Canadian constitutional law for its clear exposition of the nature of judicial review.

When Sir John A. Macdonald introduced a bill to establish a supreme court for Canada on 21 May 1869, Ritchie wrote a vigorous and perceptive critique of the draft legislation. Although he strongly supported the need for an appellate tribunal of last resort “whose precedents would be a rule of decision for the Courts of all the Provinces,” he equally strongly disapproved of the exclusive and concurrent jurisdiction that the bill would give the proposed court. In his opinion parliament lacked the authority to grant the jurisdiction; moreover, he feared such a court would “weaken and enfeeble” supreme courts in the provinces. He was also opposed to retaining the full extent of the existing appeal to the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council. Retention not only flew in the face of the notion of self-government, but was expensive, leaving the unfortunate litigant “a gray headed man with empty pockets.”

This early attempt to establish the court was not realized. However, as Ritchie neared the end of his tenth year as New Brunswick’s chief justice in 1875, the Liberal government of Alexander Mackenzie succeeded in establishing a court of appeal for the dominion [see Télesphore Fournier]. The minister of justice, Edward Blake*, while wrestling with the British government over the question of continued appeals to the Privy Council, named the first six members of the court. On 8 Oct. 1875 Ritchie was made a puisne justice of the Supreme Court of Canada; the chief justiceship of New Brunswick then went to John Campbell Allen. Ritchie’s appointment was greeted with widespread approval. In Saint John it was said that the wisdom of the “eminent jurist” was to be “extended to a wider and more important sphere.” The Toronto-based Canada Law Journal, while lukewarm toward the other non-Ontario judges on the new court, praised Ritchie as being of “strong will and decided views. . . . This appointment is an excellent one.”

The new Supreme Court endured what a subsequent chief justice, Bora Laskin*, termed an “uneasy infancy.” It was criticized in parliament, in the legal press, and even within the court itself. However, a study of the work of the tribunal from its inception in 1875 until Ritchie’s death in 1892 reveals that Ritchie provided stability and strength to the court. Appointed just a few weeks short of his 62nd birthday, he brought to it 20 years of judicial experience. Although initially its eldest member, he enjoyed robust good health: the court’s first registrar, Robert Cassels, reported that he was “endowed with a splendid physique, tall, well built, and athletic in frame, his energetic manner and bearing indicated the great reserve of nervous power which has assisted a fine mind to do its work to the best advantage.” Except for illness between 25 Jan. and 30 April 1889, he rarely missed a sitting of the court in almost 17 years. By contrast the first chief justice, William Buell Richards*, was in poor health even when appointed in 1875. During Richards’s absence from the bench from 3 June 1878 until his resignation on 9 Jan. 1879, there were 13 reported decisions. Of these Ritchie wrote what must be regarded as the most significant majority decisions in more cases than any other judge.

Upon Richards’s resignation, Ritchie was named by Sir John A. Macdonald to fill the vacant chief justiceship, a position he assumed on 11 Jan. 1879. Ritchie’s tenure would include the longest period of stability in court personnel in the institution’s history. There were no changes in the puisne judges between 14 Jan. 1879 and 3 May 1888. When the new chief justice assumed his post, the young court was still experiencing difficulties in establishing its position in the eyes of the legal community. In parliament several attempts were made between 1879 and 1881 to abolish the tribunal completely. Macdonald believed that Canadians would come “to consider it as one of the tribunals of which they should be proud,” but that pride was slow to develop. The legal community was, in a very Canadian way, reluctant to accept the home-grown institution. In 1882 the Supreme Court was described in the Canada Law Journal as having “so far been a failure.” There was discontent about delays in the rendering and printing of decisions. Observers complained as well about the court’s tendency to issue multiple judgements. This criticism was weak, because the practice was in line with common-law tradition followed by both the House of Lords and the United States Supreme Court. However, Canadian jurists had been spoiled by single opinions written by the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council.

The Supreme Court during the Ritchie era was also criticized for “infirmities of a personal nature,” and for a lack of consultation and cooperation among its members. Ritchie has been accused by historians of having “clearly failed to mould the individual justices into an effective, harmonious unit.” Certainly there were personal difficulties. Mr Justice Samuel Henry Strong*, described by a lawyer as possessing “a shocking bad temper,” was undoubtedly the main culprit. In 1880 he wrote to Macdonald making a scathing attack on Mr Justice William Alexander Henry*, commenting also that “the Chief seems to think of anything rather than his judicial work and is never ready with his judgments.” In fact it was Strong who appears to have been most responsible for problems in the reporting of decisions. Observers noted that the chief justice also had a temper, but, they added, he kept it “well under control, and his relations with all who came in contact with him were most happy.”

Many of the problems associated with the Ritchie court were the result of the circumstances of its founding. Canadians were still adjusting to their new dominion status and continued to identify with their own regions. Their regionalism was reflected in legal circles, which, particularly in Ontario and Quebec, looked more favourably upon courts in Toronto, Montreal, and Quebec City than upon the Supreme Court in Ottawa. Indeed, there were suggestions that if the court was moved to Toronto both suitors and judges would benefit from the legal talent around Osgoode Hall. Concern about the ability of the English Canadian members of the court to deal with matters of Quebec civil law and of the French Canadians to cope with common-law questions also brought proposals to abolish the institution.

The overriding factor in the slow acceptance of the court’s authority was simply that it was not the true court of last resort for the dominion. Its decisions could be appealed to the Privy Council, and even more damaging was the fact that appeals could bypass it altogether and go direct from the highest provincial court to the Privy Council. Not only did the situation preclude the development of an authoritative Canadian court, but the continued presence of the Privy Council meant that Ritchie and his colleagues were bound by the principles and decisions of that higher tribunal.

Despite the difficulties of the court, Ritchie handed down many significant decisions during his 17 years in Ottawa. In The St. Lawrence & Ottawa Railway v. Lett, he held in 1885 that the death of a woman caused by the negligence of the railway was a substantial loss entitling the husband and children to recover damages. With Henri-Elzéar Taschereau* and John Wellington Gwynne* dissenting, he wrote: “How it can be said that the loss of such a wife and mother is not a substantial injury but merely sentimental, is, to my mind, incomprehensible.” This decision continues to be cited with approval. In the Manitoba school question case, Barrett v. the City of Winnipeg, the Supreme Court in 1891 unanimously struck down the Manitoba Public Schools Act of 1890, because it threatened denominational school rights which Catholics had enjoyed in practice when the province joined confederation. Ritchie found that the act “prejudicially” affected a group when they were taxed to support schools of which they could not conscientiously avail themselves. Unfortunately, this enlightened decision was overturned by the Privy Council. Some years earlier, in 1877, Ritchie had written a strong decision in Brassard et al. v. Langevin, known as the Charlevoix election case. He held that certain sermons and threats by parish priests in favour of Hector-Louis Langevin* constituted undue influence; their message was that a vote for the Liberal candidate, Pierre-Alexis Tremblay*, was a grievous sin. Ritchie considered the case to involve “grave questions of constitutional law” and maintained that “there shall be no undue influence or intimidation to force an elector to vote or to restrain him from voting in a particular manner.” Holding that no clergyman of any faith was above the law, and finding the priests to be agents of Langevin, the court declared the election void. Ritchie’s decision is evocative of some of the reform principles he had advocated during his political career in New Brunswick. He was not a great innovator, but he was a good, conscientious, and independent judge.

Chief Justice Ritchie was called upon to perform certain vice-regal functions. During the absences of the governor general, Lord Lorne [Campbell*], from 6 July 1881 to January 1882 and between 6 Sept. and December 1882, Ritchie acted as deputy governor of Canada. He was knighted on 1 Nov. 1881, the honour being made retroactive to 24 May. In March 1884 he was appointed deputy to Governor General Lord Lansdowne [Petty-Fitzmaurice*].

The appointment to the Supreme Court at Ottawa placed Ritchie, his wife, and family in a new social environment. As Ottawa attempted to assert for itself a stature worthy of its political significance, the establishment of the new court in 1875 “added six new stars to the social firmament.” Shortly after the swearing-in, Governor General Lord Dufferin [Blackwood*] hosted a grand dinner for the new justices, and Ritchie soon found himself a prominent member of the Ottawa scene. He also became involved in the city’s fledgling cultural circles. As chairman of an 1879 committee to establish an art association, a group that included Allan Gilmour, Edmund Allen Meredith, and others, he commented on “the want, very severely felt, of a school where our young people might be taught drawing, painting and sculpture, under good professional teachers.” He served as president of the Art Association in 1882–83. He also had an interest in building and architecture. While still in Saint John he had owned some property which George Stewart*, a contemporary writer, described as a source of diversion for him: “The judge, whose taste for architecture is well known, often planned the style of building he would like to put up. . . . It was no uncommon thing for him to draw near to a table, and with pencil and paper plan buildings of infinite variety. It was good employment for the mind, and less expensive than actual building.”

An Anglican, Ritchie attended St George’s Church in Ottawa. In 1889 the rector, Percy Owen-Jones, introduced changes to the service that evoked strong objections from many of the congregation, including the chief justice. Ritchie, a staunch low-church Anglican, found the chanting of the kyrie “obnoxious,” and his objections, combined with those of other low churchmen in the parish, led to the resignation of the rector the following year. His views reflected his family upbringing and had perhaps been reinforced by the teachings of McCulloch at Pictou, whose writings included a tract entitled Popery condemned by Scripture and the fathers . . . (Edinburgh, 1808).

In May 1892 the chief justice was stricken with bronchitis. It seemed initially that the time spent away from Ottawa during the summer would lead to recovery. However, upon returning to the capital on 6 September, Ritchie suffered a relapse, and he died at home on 25 September at the age of 78. His tenure as chief justice of the Supreme Court – 13 years, 8½ months – established a record not yet surpassed. He was survived by his wife and 13 children. Lady Ritchie had shared in her husband’s rise to prominence in Ottawa, and continued to play an active role in the capital’s society. She was a founder and first president of the Ottawa chapter of the National Council of Women of Canada and served as an original board member and a governor of the Victorian Order of Nurses. Lady Ritchie died on 7 May 1911.

There are, unfortunately, no surviving papers of Sir William Johnston Ritchie, from either his days in Saint John, N.B., or his time in Ottawa. The following are his only published writings, apart from his decisions in law reports: “The Chesapeake”: the case of David Collins et al. . . . before His Honor, Mr. Justice Ritchie, with his decision (Saint John, 1864), and Observations of the chief justice of New Brunswick on a bill entitled “An act to establish a supreme court for the Dominion of Canada” (Fredericton, 1870).

ACC, Diocese of Ottawa Arch., St George’s Anglican Church (Ottawa), minutes of vestry meetings, 1889–90: 64–81, 90–99. AO, RG 22, ser.354, no.2187. NA, MG 26, A: 148624–40, 148652–61; RG 31, C1, 1881, 1891, Ottawa. N.B. Museum, J. C. Webster papers, packet 73. QUA, 2112, boxes 2–3. St Paul’s Episcopal Chapel (Rothesay, Scot.), Copy of marriage certificate for W. J. Ritchie and Martha Strang, 21 Sept. 1843 (original certificate in possession of James Smellie, Ottawa). Supreme Court of Canada (Ottawa), Minute-books, MI (8 Nov. 1875–11 April 1884); MZ (12 April 1884–16 Nov. 1891); M3 (17 Nov. 1891–7 Dec. 1900). Canada Law Journal (Toronto), new ser., 11 (1875): 265–66; 16 (1880): 73–75, 99–100; 18 (1882): 87–88; 28 (1892): 484. G. E. Fenety, Political notes and observations . . . (Fredericton, 1867); “Political notes: a glance at the leading measures carried in the House of Assembly of New Brunswick, from the year 1854,” Progress (Saint John), 1894, collected into a scrapbook (Fredericton, 1894; copies in the NA Library, N.B. Museum, and CIHM, ser. no.06725). Legal News (Montreal), 1 (1878): 140–41. N.B., House of Assembly, Journal, 24 Feb. 1848; Supreme Court, New Brunswick Reports (Saint John and Fredericton), vols.8–16 (1854–77), reports for 1855–75. Reports of the Supreme Court of Canada, comp. George Duval et al. (64v., Ottawa, 1878–1923), 1–20. Stewart, Story of the great fire. Head Quarters (Fredericton), 22 Aug., 5 Sept. 1855. Morning Freeman (Saint John), 2 Dec. 1865. Morning Journal (Saint John), 1 Dec. 1865. Morning News (Saint John), 20 Aug. 1855; 1, 6 Dec. 1865. New Dominion and True Humorist (Saint John), 16 Oct. 1875. Ottawa Daily Citizen, 16 June, 19 Nov. 1879; 10 April 1883; 26 Sept. 1892. Ottawa Evening Journal, 8 May 1911. Reporter and Daily and Tri-Weekly Times (Halifax), 30 Jan. 1879. St. John Daily Sun, 26 Sept. 1892. N.B. vital statistics, 1856–57 (Johnson). Gwyn, Private capital. Lawrence, Judges of N.B. (Stockton and Raymond). MacNutt, New Brunswick. J. G. Snell and Frederick Vaughan, The Supreme Court of Canada: history of the institution ([Toronto], 1985). Robert Cassels, “The Supreme Court of Canada,” Green Bag (Boston), 2 (1890): 241–45. Bora Laskin, “The Supreme Court of Canada: a final court of and for Canadians,” Canadian Bar Rev. (Toronto), 29 (1951): 1038–79. Frank MacKinnon, “The establishment of the Supreme Court of Canada,” CHR, 27 (1946): 258–74. M. C. Ritchie, “The beginnings of a Canadian family,” N.S. Hist. Soc., Coll., 24 (1938): 135–54.

Cite This Article

Gordon Bale and E. Bruce Mellett, “RITCHIE, Sir WILLIAM JOHNSTON,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 12, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed February 21, 2026, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/ritchie_william_johnston_12E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/ritchie_william_johnston_12E.html |

| Author of Article: | Gordon Bale and E. Bruce Mellett |

| Title of Article: | RITCHIE, Sir WILLIAM JOHNSTON |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 12 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1990 |

| Year of revision: | 1990 |

| Access Date: | February 21, 2026 |