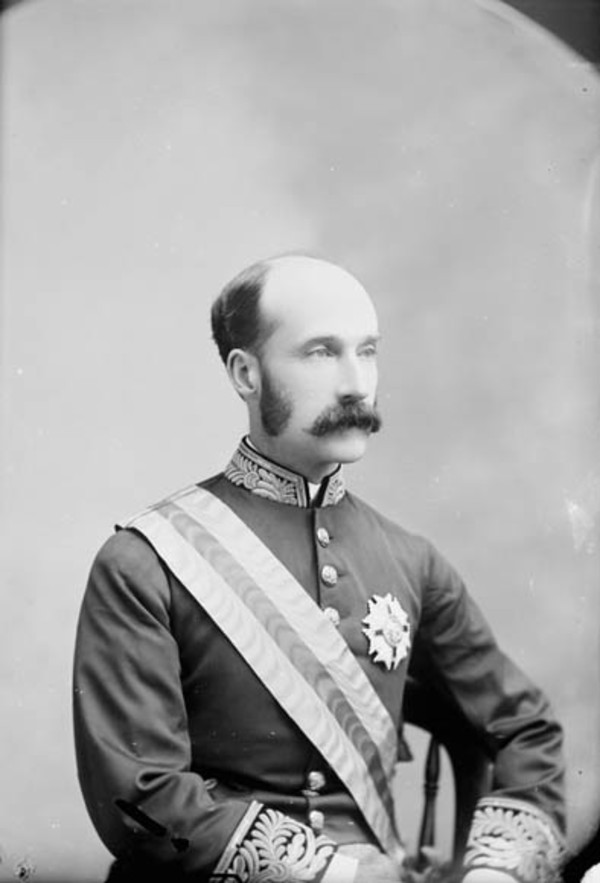

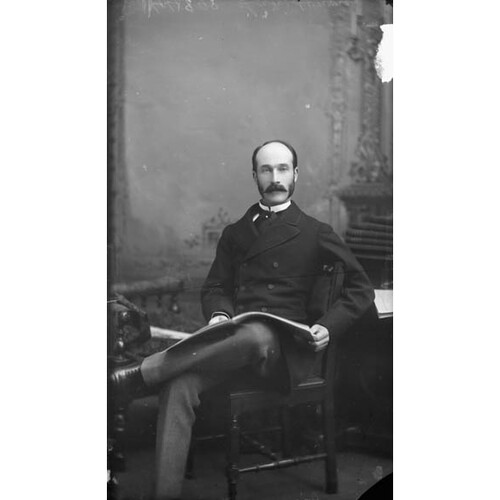

PETTY-FITZMAURICE, HENRY CHARLES KEITH, 5th Marquess of LANSDOWNE, governor general; b. 14 Jan. 1845 in London, England, elder son of Henry Petty-Fitzmaurice and Emily Jane Mercer Elphinstone de Flahault; m. there 8 Nov. 1869 Lady Maud Evelyn Hamilton, and they had two sons and two daughters; d. 3 June 1927 in Clonmel (Republic of Ireland).

Henry Charles Keith Petty-Fitzmaurice was known as the Earl of Kerry during the three years that his father held the marquessate of Lansdowne. He succeeded to the higher title in 1866, and to the Liberal traditions of his family. Educated at Eton and Balliol, Oxford, the slight, dark-complexioned Lansdowne missed a first class owing to his great interest in sports and life at Oxford. He came early to administrative office: a lord of the Treasury in 1868 under William Ewart Gladstone, under-secretary for war in 1872–74, and under-secretary for India in 1880. He then resigned owing to his dislike of Gladstone’s Irish policies; Lansdowne had large estates in Ireland, including a home, Derreen, near Kenmare in County Kerry. By the 1880s a Conservative, he was chosen in May 1883 to succeed the Marquess of Lorne [Campbell*] as governor general of Canada; he was formally appointed on 18 August, arrived at Quebec City on 22 October, and assumed office the following day.

Lansdowne was a highly intelligent and able administrator. With the possible exception of Lord Lisgar [Young*], Prime Minister Sir John A. Macdonald* found him the most perspicacious of the governors he had served before and after confederation. Lansdowne was sensitive to the questions that arose in the Saskatchewan River valley in 1884–85. All for making accommodation with the Métis, he suggested to Macdonald on 9 Aug. 1884 that some means be found of giving employment to certain of their leaders. To Lansdowne’s mind, the best place for Louis Riel* might well be on the Council of the North-West Territories. As to the land question [see Gabriel Dumont*], he asked Macdonald, “Would it not be possible to send out a strong commission with powers to deal promptly & . . . liberally with these [land] claims?” He also took a great interest in the Canadian Pacific Railway, travelling to the end of steel in September 1885 and riding on horseback across the 47-mile gap in British Columbia between the two railheads. He was to drive the last spike, but weather delayed completion of the line and when he telegraphed Macdonald in October asking if he should return to Ottawa, for the final decision concerning Riel, Macdonald said yes. The last spike was driven instead by Donald Alexander Smith*.

Macdonald and his ministers were struck by Lansdowne’s early grasp of the complex, often difficult nature of British-Canadian relations. His diplomatic skills, preparedness, and unexpectedly strong support for Canadian interests were particularly evident in the negotiation of the fisheries treaty with the United States in 1886–87. Fisheries minister George Eulas Foster* was strongly impressed, as was another participant, justice minister John Sparrow David Thompson*, who had liked Lansdowne from the moment they met in 1885.

Despite Lansdowne’s aptitude, being an Irish landlord made him vulnerable. From the time of his arrival he had attracted the ire of Irish nationalists in North America and there were Fenian threats against his life. In 1884, for example, a Fenian from Chicago concealed himself in the winter woods at Rideau Hall for an entire day waiting for Lansdowne to appear. He failed to show, but his son Lord Kerry was skating on a rink nearby; “I could have shot the boy,” the Fenian reported, “but my heart failed me.”

Lansdowne liked Canada, “its visions of winter, with its clear skies, its exhilarating sports, and within the bright fire of Gatineau logs, with our children and friends gathered round us.” He built a summer retreat on the Rivière Cascapédia in the Gaspé, where the salmon fishing thrilled him. But the British government needed him for India, and he left Canada in June 1888 for a six-year term as viceroy. Macdonald would write him from time to time; to one letter Lansdowne replied, on 23 June 1889, “I fancied myself back in my study in Ottawa, listening to your confidences as to House of Commons prospects, & difficulties, unsuspected by the outside world, within the Cabinet.”

After India, Lansdowne went home to the British cabinet, where he served as secretary of state for war in 1895–1900. During the South African War, for which he had to sort out Canadian and other colonial offers of troops, he was unjustly criticized for British military failures. A good minister, he took full responsibility and said nothing, though the real fault lay with his military advisers. As foreign secretary from 1900 to 1905, he negotiated the Anglo-Japanese alliance of 1902 and the Entente Cordiale with France in 1904. He revisited Canadian affairs in 1902–4 over the settlement of the Alaska boundary dispute, on which he worked closely with Governor General Lord Minto [Elliot*], who had been his military secretary in Canada. Lansdowne became leader of the Unionist (Conservative) party in the House of Lords in 1903. His pledge, with others, in early August 1914 to bring Unionist support to France’s side had the effect of committing cabinet to war. A minister without portfolio in 1915–16, Lansdowne was soon struck by its phenomenal human and financial costs. In a memorandum to cabinet in November 1916, he boldly called for a negotiated peace; on making this sentiment public a year later, he was reproached within and without his party. The veteran servant nonetheless continued to attend the House of Lords. He was devoted to his Irish home, Derreen, which he rebuilt after its destruction by Irish irregulars in the 1922 troubles. He died of a heart attack at the home of his daughter in Ireland, and was buried at Bowood Park, his estate near Calne in England.

Lansdowne could well have matured quietly into a country gentleman; he was a considerable sportsman, a good shot, a rider to hounds, an expert angler. Instead, at an early age he had become a British public official, one of the best of the breed. Perceptive, honest, and hard-working, he was ready to take up responsibility, shoulder consequences, and not blame subordinates. He had that excellent combination of intelligence and patience, joined to a knack for acting at the right time in the right way. His life and its ethos illustrate how and why the British empire succeeded as it did, and lasted so long. The best of the British upper class was very good indeed.

[The Lansdowne papers are under the control of the 8th Marquess of Lansdowne at Bowood, England. In 1963 the sections relevant to Canada were microfilmed; they are in NA, MG 27, I, B6, together with a few originals. There is a fine run of Lansdowne correspondence in the Sir John A. Macdonald papers, NA, MG 26, A , vols.84–88. The DNB has an extended notice of Lansdowne by his son the 6th Marquess. There is also a good biography of him by [Thomas Wodehouse Legh Newton, 2nd Baron] Newton, Lord Lansdowne: a biography (London, 1929). A portrait of Lansdowne hangs in the speaker’s office in Canada’s House of Commons. p.b.w.]

Times (London), 6 June 1927. D. [G.] Creighton, John A. Macdonald, the old chieftain (Toronto, 1955; repr. 1965). Lord Minto’s Canadian papers: a selection of the public and private papers of the fourth Earl of Minto, 1898–1904, ed. and intro. Paul Stevens and J. T. Saywell (2v., Toronto, 1981–83). Carman Miller, Painting the map red: Canada and the South African War, 1899–1902 (Montreal and Kingston, Ont., 1993). P. B. Waite, Canada, 1874-1896: arduous destiny (Toronto and Montreal, 1971); The man from Halifax: Sir John Thompson, prime minister (Toronto, 1985). W. S. Wallace, The memoirs of the Rt. Hon. Sir George Foster, p.c., g.c.m.g. (Toronto, 1933).

Cite This Article

P. B. Waite, “PETTY-FITZMAURICE, HENRY CHARLES KEITH, 5th Marquess of LANSDOWNE,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 15, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed December 24, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/petty_fitzmaurice_henry_charles_keith_15E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/petty_fitzmaurice_henry_charles_keith_15E.html |

| Author of Article: | P. B. Waite |

| Title of Article: | PETTY-FITZMAURICE, HENRY CHARLES KEITH, 5th Marquess of LANSDOWNE |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 15 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 2005 |

| Year of revision: | 2005 |

| Access Date: | December 24, 2025 |