Source: Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

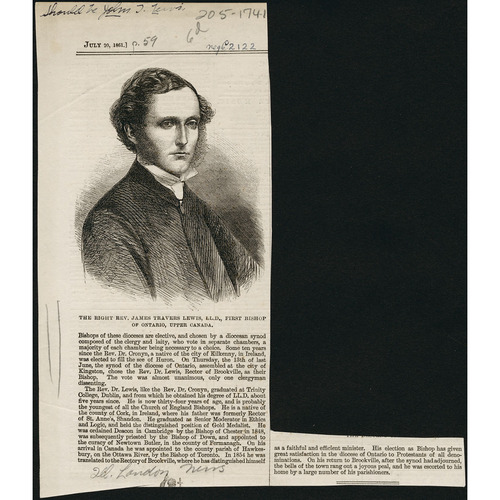

LEWIS, JOHN TRAVERS, Church of England clergyman, archbishop, and author; b. 20 June 1825 at Garrycloyne Castle, near Cork (Republic of Ireland), eldest son of the Reverend John Lewis and Rebecca Olivia Lawless; m. first 22 July 1851, in Toronto, Anne Henrietta Margaret Sherwood (d. 1886), and they had six daughters and five sons, of whom four daughters and two sons survived to adulthood; m. secondly 20 Feb. 1889 Ada Maria Leigh of Manchester, England; they had no children; d. 6 May 1901 at sea en route to England.

Travers Lewis’s father, who was rector at Shandon, near Cork, died suddenly of the plague in 1832. This abrupt loss and Lewis’s upbringing at his grandparents’ country seat in Garrycloyne, among hard-riding gentry, reinforced the youth’s taciturn and determined disposition, which would characterize him for life. So too did his fine scholarly performance at Trinity College, Dublin, where he studied under eminent divinity professor Charles Richard Elrington, the premier expositor of the 17th-century views of Irish archbishop James Ussher on church polity. This experience gave scope and resilience to Lewis’s strong grasp of church doctrine and polity. He graduated gold medallist in theological studies in 1847. Although he did not know it then, this education, and his exposure in Dublin to controversy within the church in Ireland, was perfect for a young priest going to the colonies, where change was the order of the day.

Lewis was raised to the diaconate at Christ’s College Chapel in Cambridge, England, on 16 July 1848 and to the priesthood at Lisburn Cathedral in County Antrim (Northern Ireland) on 23 Sept. 1849. In the meantime he served as priest at Newtownbutler in County Fermanagh. These were bad times in Ireland because of the Great Famine and Lewis’s mother emigrated to Canada in 1848, settling near London. The next year Lewis followed her to Canada as a missionary of the Society for the Propagation of the Gospel. He was posted to Hawkesbury, on the Ottawa River. In 1851 he married a daughter of former attorney general Henry Sherwood*, who had connections to Brockville. Lewis reaped the benefit of this marriage when, in 1854, he was manœuvred into the secure incumbency of St Peter’s Church in Brockville.

This appointment was patronage, of course, but it was not through patronage that Lewis, at the very young age of 35, was elected a bishop. As it became known that the eastern part of Upper Canada was to be separated from the diocese of Toronto and a new bishopric formed, Kingstonians, by applying to Canterbury for a nominee, moved to counter the wish of Bishop John Strachan* that a free election be held. In addition, they attempted to secure the appointment from Ireland of Thomas Hincks, brother of former co-premier Francis Hincks*. There was, however, a good deal of dissatisfaction elsewhere in the future diocese over the reputedly low-church stance of Kingston’s Anglicans. Lewis allowed himself to emerge as the leader of this discontent. When the election was held in June 1861, the duly authorized voters overwhelmed Kingston, and its few outside supporters, by making Lewis bishop with a huge clerical majority and a sizeable lay majority, rejecting in the process Strachan’s personal nominee, Archdeacon Alexander Neil Bethune*. For the next year Lewis became a diocesan target, since Strachan and the governor general failed to meet English deadlines to secure the royal patent establishing both the diocese of Ontario and the bishopric. Lewis was not consecrated until March 1862.

Lewis’s initial difficulty in reconciling diocesan policy to the expectations of small but growing urban communities was never resolved. In Kingston, his chosen see-city, he was faced in the fall of 1862 with a revolt in his cathedral, St George’s, against the appointment of William B. Lauder to succeed George Okill Stuart* as dean. Continuing discontent in Kingston deprived Lewis of a proper see-house. With Ottawa growing as Canada’s capital, he saw an opportunity to move his person, if not the diocesan administration, to that place. He settled there in 1870 but again support and building programs evaporated, and in the late 1880s he returned to Kingston. The ailing bishop was still negotiating with his diocese about a see-house and matters of stipend in the 1890s. Arrangements for a settlement with the old man were not completed until just months before his death in 1901.

The difficulties and the clashes in various urban parts of Lewis’s territory had not prevented him from initiating a spectacular program of parish extension and firmly basing it upon a realistic administrative and financial structure. His diocese was huge: it was bounded by the Ottawa and St Lawrence rivers, and by a line running north from Trenton. Lewis was the first diocesan in Canada to have his synod incorporated, in 1862, and thus do away with the need for church societies, the traditional money-raisers of the Canadian church. His reasoning was that Anglicans throughout the diocese, and not just the societies, should be directly responsible for their internal mission endeavours. In a diocese where the greatest need, and the greatest generosity, resided in the country areas, and yet where control was habitually urban, this was a practical approach.

Lewis augmented organized planning within the diocese by tapping the generosity in England of the Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge and the SPG. He had secured steady funding in the United Kingdom by personal canvass in 1862 and he subsequently assured a continuing flow through repeated visits that involved preaching for money. Part of the strength that sustained the mission program undoubtedly lay in the bishop’s administrative capacity, but support also came from a number of dedicated clergy and lay men and women. With Lewis’s encouragement, the Woman’s Auxiliary was founded in 1885, first in the diocese of Ontario and then in the ecclesiastical province of Canada, which embraced the six eastern Canadian dioceses. Along with Mrs Roberta E. Tilton, Annie Lewis, the bishop’s wife, was a founder. At a time when the Canadian church as a whole was faltering in its mission work, the women restored respectability and solvency. The overall result of the mission program was that the number of parishes grew from 46 to 113 in 1894; the diocese was then still financing 48 of those parishes in varying degrees and administering a support budget of over $10,000. That such a poor area as eastern Ontario could divide, forming the diocese of Ottawa in 1896, with little evidence of real hardship, was a testament to Lewis’s foresight.

In time Lewis’s visits to Britain also became necessary to recruit health that was frail, so that his absences were remarked upon and criticized. This censure was hardly fair. Much of his large diocese could be traversed only on snow-roads at harsh times of the year. Lewis almost died of a severe pulmonary condition in 1867, and after 1872 his health was always fragile. His scheme of expansion was thus frustrated, but never overthrown, by physical obstacles. His marriage in 1889 to a rich philanthropist relieved him from abiding penury and may have saved or at least prolonged his life.

As Lewis struggled throughout his episcopate to meet the administrative needs of his diocese, he continued to find intellectual challenge. Into the 1890s, in sermons, lectures, and articles, he participated in debates on a host of controversial topics, including agnosticism or “modern thought,” ecclesiastical polity, ongoing discontent within his diocese, the “heresies” of the Plymouth Brethren, and marriage to the sister of a deceased wife. In the everlasting conflict between high and low Anglicans, Lewis, of high-church tendency, loyally supported his low-church priests but endeavoured not to add to their number, especially from the graduates of Wycliffe College, Toronto [see James Paterson Sheraton]. Enduring recognition came from Lewis’s leading role in getting the British Association for the Advancement of Science to meet in Montreal in 1884 – its first gathering outside the British Isles. The following year Governor General Lord Lansdowne [Petty-Fitzmaurice*] presented him with a medal for his “important services in the cause of literature and science.” The recipient of numerous honorary degrees, he had received credit too for his supposed seminal part in bringing about the first international conference of Anglican bishops at Lambeth Palace, England, in 1867. His role has been overplayed by some people, among them his second wife in her biography of him. It remains true, however, that it was Lewis’s motion at the provincial synod of 1865, expressing fear that the revival in Canada of “active powers of Convocation should leave us governed by canons different from those in force in England and Ireland,” that Bishop Francis Fulford* forwarded to the archbishop of Canterbury. This motion sparked the train of events leading to Lambeth 1.

In his old age, in January 1893, Lewis succeeded John Medley* as metropolitan of the ecclesiastical province of Canada. The following April, when the first General Synod of the Church of England in Canada resolved that each metropolitan also be designated archbishop of his see, Lewis became archbishop of Ontario. Despite this honour, which his flock had sought for him, Lewis disapproved of General Synod as a typically Canadian, top-heavy administrative superstructure. In 1900 he resigned as metropolitan. The next year, in extremely poor health, he attempted to travel to England but died at sea; he was buried in the churchyard of the parish of St Lawrence at Hawkhurst, Kent, where his daughter Rebecca Olivia Loyd lived.

As bishop, John Travers Lewis had experienced enormous strains. Ten years is a long colonial bishopric. Lewis had to manage a pioneering diocese for a staggering 40 years, during which time he maintained and largely secured his objectives. Indeed, his considerable achievements, which made his modest diocese a byword of mission growth and success, spread to much of the rest of the Anglican church in Canada.

[The author’s full-length study of Lewis, A bishop and his people: John Travers Lewis and the Anglican diocese of Ontario, 1862–1902 (Kingston, Ont., 1991), gives full information on the primary and secondary sources available for his career. Lewis’s publications include various sermons, addresses, and episcopal charges, listings for which appear in Canadiana, 1867–1900 and the CIHM Reg.

Useful secondary sources include the following: Canadian men and women of the time (Morgan; 1898); Chadwick, Ontarian families, 1: 140–42; Crockford’s clerical directory . . . (London), 1854–1900; Cyclopædia of Canadian biog. (Rose and Charlesworth), vol.1; K. C. Evans, “The intellectual background of Dr. John Travers Lewis, the first bishop of the Anglican diocese of Ontario,” Historic Kingston (Kingston), no.10 (1962): 37–45; [A. M. Leigh Lewis], The life of John Travers Lewis, d.d., first archbishop of Ontario; by his wife (London, [1930]) [this biography by his widow remains useful for general information but is often inaccurate in matters of precise detail]; O. R. Rowley et al., The Anglican episcopate of Canada and Newfoundland (2v., Milwaukee, Wis., and Toronto, 1928–61); and D. M. Schurman, “John Travers Lewis and the establishment of the Anglican diocese,” To preserve & defend: essays on Kingston in the nineteenth century, ed. G. [J. J.] Tulchinsky (Montreal and London, 1976), 299–310. d.m.s.]

Cite This Article

Donald M. Schurman, “LEWIS, JOHN TRAVERS,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 13, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed April 26, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/lewis_john_travers_13E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/lewis_john_travers_13E.html |

| Author of Article: | Donald M. Schurman |

| Title of Article: | LEWIS, JOHN TRAVERS |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 13 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of revision: | 1994 |

| Access Date: | April 26, 2025 |