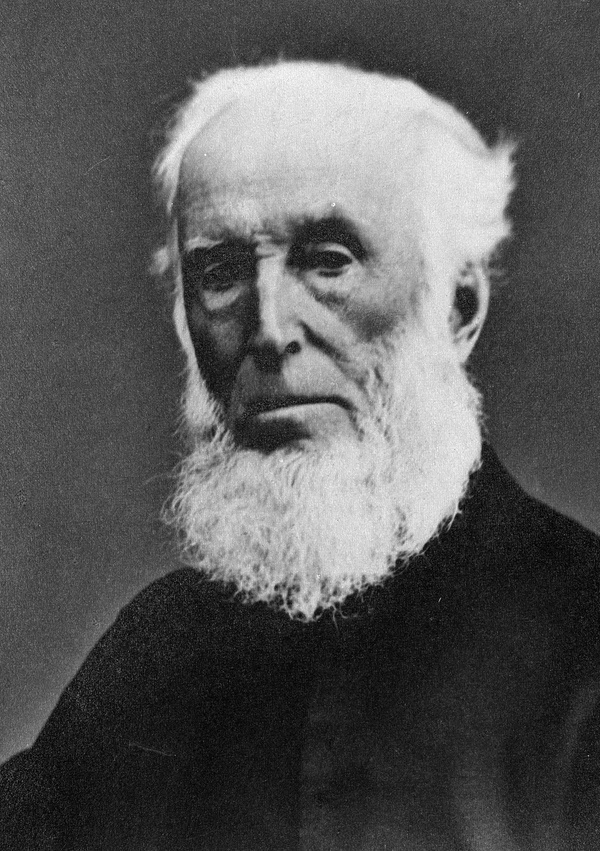

BETHUNE, ALEXANDER NEIL, Church of England clergyman and bishop; b. 28 Aug. 1800 at Williamstown, Charlottenburg Township, U.C., son of the Reverend John Bethune*, a loyalist, and Véronique Waddin; m. Jane Eliza, daughter of James Crooks*, and they had ten children, including Robert Henry*, a founder and, for more than 20 years, cashier of the Dominion Bank, and Charles James Stewart*, who became headmaster of Trinity College School, Port Hope; d. 3 Feb. 1879 at Toronto, Ont.

A clergyman of the Church of Scotland, John Bethune emigrated to the Carolinas to be chaplain of a regiment of the Royal Militia. Captured soon after the outbreak of the American War of Independence, he made his way to Halifax and then lived for a number of years in Montreal, where he established its first Presbyterian church, the St Gabriel Street Church. In 1787 he moved to Charlottenburg; there Alexander Neil, the eighth of his nine children, was born. Other children were James Gray*, Angus*, and John Bethune.

From 1810 to 1812 Alexander Neil was a student at the grammar school run by the Reverend John Strachan* at Cornwall, Upper Canada. It was probably owing to Strachan’s influence as well as that of Bethune’s mother, who had a Reformed Church background, that both John and Alexander Neil entered the ministry of the Church of England. Alexander Neil’s movements from 1812 to 1819 are not known for certain; he may have continued his schooling under his older brother John, incumbent in Elizabethtown and Augusta Townships from 1814 and then at Montreal from 1818, for in the autumn of 1819 Alexander Neil wrote from Montreal that he had determined to go to York (Toronto) “to place himself under the care and direction of Dr. Strachan, as a Student of Divinity, and to connect with this pursuit, such assistance in the Grammar School as a youth of nineteen could be expected to render.”

From 1819 to 1823 Bethune remained at York as a student of divinity supported by the Society for the Propagation of the Gospel. He also assisted Strachan at St James’ Church as an usher. On 24 Aug. 1823 Bethune was made a deacon by Bishop Jacob Mountain* in Quebec City. The following year, on 26 September, he was ordained a priest by Bishop Mountain. He had charge of the parish of The Forty (Grimsby), where he had served his diaconate, and was also responsible for an out-station at Twelve Mile Creek (St Catharines). In 1827 Bethune became the incumbent of the parish of Cobourg; he was later its rector and served there until 1867. In 1831 he made the first of a number of trips to England on behalf of the Church of England in the colony, on this occasion as secretary to Bishop Charles James Stewart* of Quebec, in support of the University of King’s College at York and the Church of England’s rights to the clergy reserves in Upper Canada, questions on which his views resembled closely those of Strachan.

While at Cobourg, Bethune also became first editor of the Church, a weekly newspaper that commenced publication 6 May 1837. He retained this position until 1841 when he resigned it to a layman, John Kent, but in 1843 he once again became editor, commenting that “the excitement . . . amidst the clash and din of party strife, was too much for [Kent].” The decision to found a newspaper to represent “Church” opinion in the province came from the need to rally church support for its stand on the clergy reserves. Bethune, a man of not inconsiderable learning, had made a careful study of the whole question, and Strachan, chairman of the newspaper’s committee, found in Bethune a man whom he could trust and in whom he could confide. Indeed Strachan directed much of the editorial policy.

At the beginning the newspaper had the respect of all sides of church opinion, for then, Bethune recalled, party spirit within the church was hardly known. But opposition was not long in developing: in 1841 Featherstone Lake Osler* noted that the Church, “Though not advocating the errors of the Oxford heresy, continually excuses them and sets forth the Church instead of Xt [Christ] set forth by the Church. The Editor . . . like the Bishop with whom he is an especial favourite is ultra high Church.” In the next 30 years, during which more than half a million Irish poured into Canada West, the Church of England acquired a pronounced evangelical, low church flavour. To men of this persuasion, Bethune was a high churchman. There were two influences on Bethune in this regard. In reaction partly to the Methodists, he saw the Church of England as “the acknowledged bulwark of the Protestant faith, against Papal despotism and superstition, and the safe-guard of Gospel truth and order against the heretical and disorganizing principles of many modern dissenters.” The other influence was Strachan, who had little respect for low churchmen. In the eyes of the Methodists and the steadily growing number of evangelicals within the church, Bethune came to be identified with the Anglo-Catholic movement which arose during the period of his editorship. His desire to be moderate and fair in assessing its leaders only exacerbated these feelings. When he wrote a balanced editorial on Henry Newman, who had gone over to the Roman Catholic Church, even Strachan admonished him.

The chief opponent of the Church was the Methodist newspaper, the Christian Guardian, edited by Egerton Ryerson*, which stoutly resisted the exclusive claims of the Church of England in the colony to the clergy reserves. Ryerson reflected the opinion of the Methodists and other bodies dissenting from the eligible established churches in objecting to government support of religious groups, on the grounds that it favoured some to the disadvantage of others and that the revenue would be better spent in such fields as public education and roads. He spoke against the bill of 1840 which proposed that the land be sold after existing obligations were honoured and the proceeds distributed to the various churches, but eventually resigned himself to the measure. Strachan, on the other hand, opposed the bill because it deprived “the national church of nearly three-fourths of her acknowledged property,” and declared that “it attempts to destroy all distinction between truth and falsehood . . . its anti-Christian tendencies lead directly to infidelity, and will reflect disgrace on the Legislature, I give it my unqualified opposition.” As for Bethune, he wrote in the Church: “we shall feel it a duty to inculcate obedience to it as the law of the land, and to render it as beneficial as possible for the object intended. It is with all well-disposed persons a subject for congratulation that a topic of grievance has thus been removed.”

Though Bethune had regarded the lands and revenues of the clergy reserves not merely as the unquestioned gift of a sovereign to his church in the colonies, but also as the only safeguard against the dissidence of many competing religious bodies, he was not built to relish the noise of battle and was visibly relieved at what he thought was a final settlement of such a vexatious issue. Bethune was a man of peace, one who wanted stability and who in the interests of quiescence would attach his loyalty to the settlement. He gladly followed the lead of Strachan, but would have been content to settle for less than his master.

When the diocese of Toronto was carved out of that of Quebec in 1839, Strachan became its first bishop and he appointed Bethune as one of his chaplains. In October 1841 Strachan asked his chaplains, Bethune, Henry James Grasett*, and Henry Scadding*, to draw up a plan for training divinity students pending the establishment of a regular college. The plan was submitted, and on 27 November Strachan announced the appointment of Bethune, though he did not have a degree, as professor of theology. The Diocesan Theological Institution opened in Cobourg in January 1842 with 15 students but was attended by indifferent success. There were complaints about both the quality of the students and their training; for the first three years Bethune was both principal and staff, and this together with the many other demands on his time helps to explain the low academic standards. But the greatest problem Bethune encountered had to do with churchmanship. As the decade wore on there appeared increasing opposition to the school on the part of the low churchmen, particularly in the western part of the province. Its opponents referred to it as a “hot bed of Tractarianism,” an accusation Strachan in particular resented as false and malicious. This difficult and often stormy part of Bethune’s ministry was brought to an end when the school was merged with the University of Trinity College, opened in Toronto in 1852.

Strachan had appointed Bethune his ecclesiastical commissary for the archdeaconry of York in 1845 with the title of “the Reverend Official.” Though burdened with responsibilities, Strachan had felt unable to relinquish the post of archdeacon of York for financial reasons, and this arrangement permitted him to devote his time to his duties as bishop. Then, in 1847, the bishop collated Bethune into the archdeaconry of York upon his own resignation from that position. Bethune gave up the editorship of the Church and became the chief administrative assistant of Bishop Strachan while remaining principal of the college. He made regular visitations of the parishes, checking church buildings and rectories, reviewing parish registers, advising on pastoral problems, and making reports to the bishop. From 1847 to 1850 he visited about 127 churches and mission stations, in an area that extended westward through the province from Oshawa. The archdeaconry was a post Bethune filled with diligence, and it immersed him in the day-to-day problems of the diocese.

Strachan prevailed upon King’s College, Aberdeen, of which both he and Bethune’s father were graduates, to confer upon his archdeacon the degree of doctor of divinity in 1847, and ten years later Trinity College conferred upon him the honorary degree of Doctor of Canon Law. In the spring of 1852 Bethune went to England at Strachan’s bidding to raise financial support for Trinity College, founded after Strachan’s former creation, the University of King’s College, had been secularized into the University of Toronto. Bethune was also his church’s spokesman in England during the final battle over the clergy reserves. He met with limited success in both tasks. He was unable to shake the determination of the Lord Aberdeen ministry to comply with the demand from the administration of Francis Hincks* in Canada that an imperial act be passed enabling the provincial legislature to make a final settlement on the clergy reserves. Nor did he receive the response to his appeal for funds which he had expected: he often felt “baffled and disappointed,” but considered that “fully £5,000 [would] be realized in all.”

In July 1857 the first subdivision of the diocese of Toronto took place when the diocese of Huron was carved out of its southwestern portion. Bethune entered the first of his three episcopal elections and lost to Benjamin Cronyn, the Irish rector of London. When the diocese of Ontario was created from the eastern portion of the diocese of Toronto in 1862, Bethune was again a candidate but withdrew before the certain success of another Irishman, the 36-year-old rector of Brockville, John Travers Lewis*. In both elections, Bethune lost to local candidates with strong popular support. In addition, however, the growing strength in numbers and influence of the evangelical, low church wing was an obstacle to Bethune; he was regarded by many of its sympathizers as a high churchman, and by some as a Tractarian. Moreover, the opposition to Strachan, fostered by his dislike of low churchmen and by his driving personality, spilled over onto Bethune, popularly regarded as the bishop’s favourite.

On 21 Sept. 1866, however, Bethune came into his own when Strachan at 88 requested a coadjutor to assist him. The synod elected Bethune on the ninth ballot, but only after Provost George Whitaker* of Trinity College, who had consistently led in the voting, asked after the eighth ballot that his name be withdrawn. Bethune had ranked third in both clerical and lay voting, taking about one-quarter of the clerical votes but one fifth of the lay vote, trailing Whitaker and Thomas Brock Fuller*. The only other serious contender was Grasett, now rector of St James’ Cathedral in Toronto. Bethune took the title of bishop of Niagara and was consecrated by Strachan in St James’ Cathedral, 25 Jan. 1867.

Later in 1867 Bethune represented the diocese of Toronto in place of the failing Strachan at the first Lambeth Conference, in England. He returned to Toronto just before Strachan’s funeral on 5 November. Bethune had succeeded his mentor on 1 Nov. 1867, and adopted as his signature “A. N. Toronto.” He resigned both the rectory of Cobourg and the archdeaconry of York. He continued as bishop of Toronto until his death in 1879.

Bethune’s tenure as second bishop of Toronto commenced with a memorial from his clergy expressing their “dutiful submission; of sincere regard for your person and office; and of our purpose, by God’s help, to do all we can to render your Episcopate a blessing to yourself and to the Diocese.” Events, however, proved the contrary. An articulate, powerful, low church laity fought the reverberations in Canada of the Oxford movement and Tractarian influence. There was a controversy over vestments with William Arthur Johnson, the most advanced of the Tractarians in the diocese. On the other hand, Grasett was asked to answer charges of “depraving the doctrine and discipline of the Church” by setting up a rival Church of England Evangelical Association in 1868 which drained off support of missionary efforts of the official Church Society. The low churchmen in 1873 created the Church Association to maintain Reformation principles, founded a rival newspaper, the Evangelical Churchman, in 1876, and established the Protestant Episcopal Divinity School (later Wycliffe College) in 1877 as a rival seminary to Trinity College for training divinity students. Finally, in 1878 the low church party thwarted Bethune’s attempt to gain the assistance of a coadjutor bishop when the laity prevented the election of Whitaker. Bethune dismissed the synod, resigned to go to the end alone. He protested, in vain, against the rival associations, but they were symptomatic of the deep divisions within the diocese.

During his episcopate the Church of England in Ontario continued to grow with the expanding population. In 1869 the question of a division of the diocese of Toronto was raised once more. The proposal was a fourfold split, with the diocese of Toronto retaining the counties of Peel, York, Halton, Ontario, and Wellington, and the remainder being divided into three districts: Northern (Simcoe County and Algoma District west to the diocese of Rupert’s Land), Western (to include the counties of Welland, Lincoln, Haldimand, and Wentworth), and Eastern (Peterborough, Northumberland, Durham, and Victoria counties). There the proposal rested until 1872 when Bethune announced that the SPG was prepared to help endow the proposed diocese of Algoma, on condition that in Canada a sum of at least £4,000 was raised for the same purpose before the end of 1875. In November 1872, Bethune, who had accepted the SPG’s offer, attended an informal meeting with the other bishops in Ottawa where it was decided to raise a new bishop’s salary immediately by assessment. The following month an election for Algoma was held but the bishop-elect declined the post. Nothing was done until the Toronto synod met in June 1873 and authorized the provincial synod to proceed to the election of a bishop for “the Northern and Missionary Diocese of Algoma.” Bishop Bethune was empowered to appoint a clergyman to supervise the work until an election was held. Frederick Dawson Fauquier*, who had studied under Bethune at Cobourg, was consecrated first bishop of Algoma in October 1873. In 1875 the diocese of Niagara was also created out of the western district, and Fuller became its first bishop.

Alexander Neil Bethune was pre-eminently a gentle and mild individual, and a contrast to Strachan, the first bishop. The Reverend John Langtry commented: “no two men could be more unlike than they. Bishop Strachan was a man of war from his youth . . . . The ideal of Bishop Bethune’s life, whether consciously or not, was that of one who was trying above all things to live peaceably with all men. He was a man of high intellectual gifts, and of extensive reading, of gentle and refined disposition, but of a reserved and unemotional character . . . . Bishop Bethune seldom or never got angry. He was distressed by the waywardness and rough tempers of others; but as the result of it all, he lived an unruffled life.”

Bethune, without Strachan’s fearless abilities as a strategist, inherited in no small measure the opposition which Strachan’s methods and policies had stirred up. It was his misfortune to be bishop at the height of the storm, and his episcopate might have appeared more successful under other circumstances.

Bethune did not show the antipathy Strachan did toward low churchmen, but he did feel them to be deficient in a sense of beauty in worship and in obligation to maintain church order and discipline. He was a “high” churchman in the sense that he maintained a high estimate of the church, its ministry, and its sacraments. He had a high (and somewhat exclusive) interpretation of the church and would never allow the doctrine of justification by faith, on which the evangelicals laid so much stress, to be divorced from Christ’s body the church. He was particularly distressed when the visible expression of the church’s unity in the diocese was rent by the creation of rival organizations to official bodies.

Bethune was an example to all in his industry, his integrity, his loving manner, and his impartiality. He possessed conviction, but was an intensely humble man. His love of beauty and correctness in worship was interpreted by many in those unsettled times simply as a sign of “high church,” and his humility was taken by many for weakness. His message was largely lost on his generation.

A. N. Bethune, The clergy reserve question in Canada (London, 1853); Memoir of the Right Reverend John Strachan, D.D., LL.D. . . . first bishop of Toronto (Toronto, 1870); Sermons, on the liturgy of the Church of England; with introductory discourses on public worship and forms of prayer (York, 1829).

PAO, A. N. Bethune papers; John Strachan letter books, 1827–39, 1854–62; John Strachan papers. Trinity College Archives (Toronto), Bethune papers. A. B. Jameson, Winter studies and summer rambles in Canada, ed. J. J. Talman and E. M. Murray (Toronto, 1943). Susanna Moodie, Roughing it in the bush or forest life in Canada (Toronto, 1913). [Ryerson], Story of my life (Hodgins). Henry Scadding, The first bishop of Toronto; a review and a study (Toronto, 1868); Toronto of old. Henry Scadding and J. C. Dent, Toronto: past and present: historical and descriptive; a memorial volume for the semi-centennial of 1884 (Toronto, 1884). John Strachan, A letter to the Rev. A. N. Bethune, rector of Cobourg, on the management of grammar schools ([York], 1829). Church (Cobourg; Toronto; Hamilton), 6 May 1837 to 1856. Church Chronicle (Toronto), 1863–70. Church of England, Synod of the Diocese of Toronto, Journal . . . adjourned meeting of the fourteenth session (Toronto), 1866; Proceedings (Toronto), 1853–64; Journals (Toronto), 1865–79. Cobourg Star, 1831, 1837–50, 1851, 1861. Dominion Churchman (Toronto), 1875–79. Society for the Propagation of the Gospel in Foreign Parts, Reports (London), 1819–60. W. P. Bull, From Strachan to Owen: how the Church of England was planted and tended in British North America (Toronto, [1937]). J. G. Harkness, Stormont, Dundas and Glengarry: a history, 1784–1945 (Oshawa, Ont., 1946). History of the separation of church and state in Canada, ed. E. B. Stimson (Toronto, 1887). A history of the University of Trinity College, Toronto, 1852–1952, ed. T. A. Reed (Toronto, 1952). The jubilee volume of Wycliffe College (Toronto, 1927). T. R. Millman, The life of the Right Reverend, the Honourable Charles James Stewart, D.D., Oxon., second Anglican bishop of Quebec (London, Ont., 1953). O. R. Rowley, The Anglican episcopate of Canada and Newfoundland (London and Milwaukee, Wis., 1928). Trinity, 1852–1952 (Toronto, 1952). R. J. Powell, “The coming of the loyalists,” Annals of the Forty (Grimsby, Ont.), I (1950). A. H. Young, “The Bethunes,” Ont. Hist., XXVII (1931), 553–74.

Cite This Article

Arthur N. Thompson, “BETHUNE, ALEXANDER NEIL,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 10, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed April 28, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/bethune_alexander_neil_10E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/bethune_alexander_neil_10E.html |

| Author of Article: | Arthur N. Thompson |

| Title of Article: | BETHUNE, ALEXANDER NEIL |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 10 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of revision: | 1972 |

| Access Date: | April 28, 2025 |