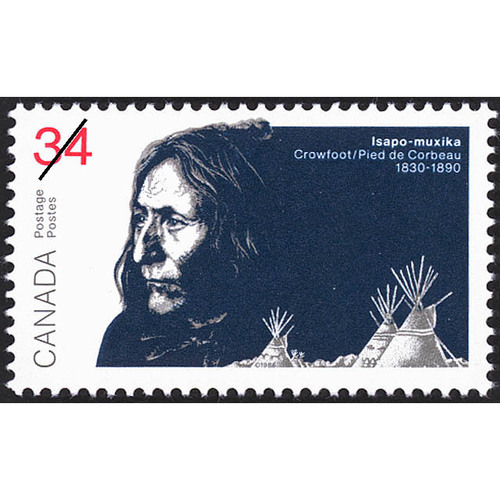

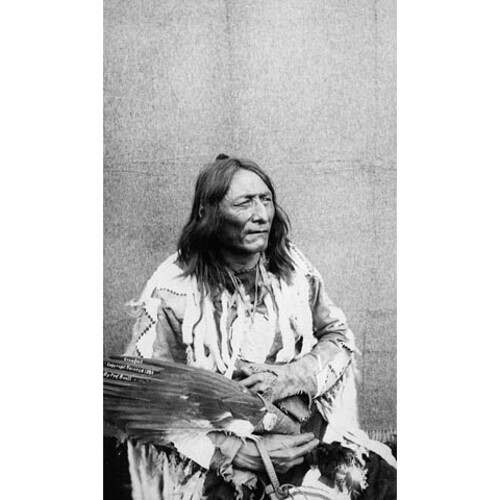

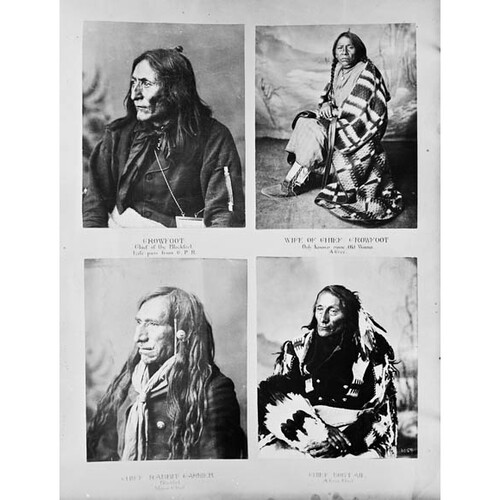

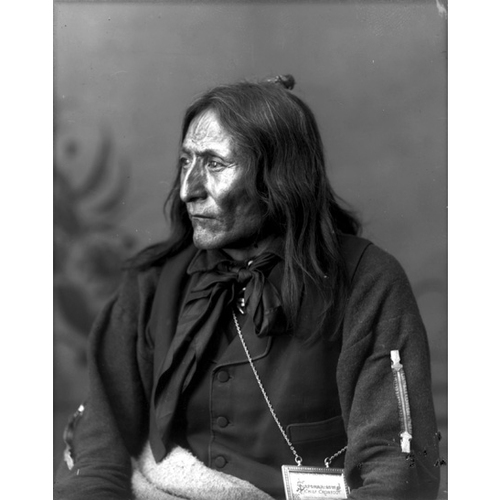

ISAPO-MUXIKA (Crowfoot, occasionally known in French as Pied de Corbeau), Blackfoot chief; b. c. 1830 near the Belly River in what is now southern Alberta, son of Blood Indians Istowun-eh’pata (Packs a Knife) and Axkyahp-say-pi (Attacked Toward Home); d. 25 April 1890, near Blackfoot Crossing (Alta).

Crowfoot was born into the Blood tribe of the Blackfoot Confederacy, which at the time also included the Blackfoot and Piegan tribes. As an infant he was given the name Astohkomi (Shot Close). When he was five his father was killed by Crow Indians and within a year Crowfoot’s mother married Akay-nehka-simi (Many Names), a member of the Blackfoot tribe. Taken to the Blackfoot tribe the boy was given the name of Kyi-i-staah (Bear Ghost), and later received his father’s name of Istowun-eh’pata.

As was customary, Crowfoot began when in his teens to accompany older warriors on raids against enemy tribes. During a raid for horses on a Crow camp, he performed bravely and was wounded, for which he was given his adult name Isapo-muxika, a name that had been owned by a relative killed several years earlier. Properly, the name Isapo-muxika translates as “Crow Indian’s big foot,” but it was shortened to Crowfoot by interpreters.

Although Crowfoot was not from a family of chiefs and was from another tribe, he soon demonstrated his leadership abilities among the Blackfoot Indians. Perhaps more important, he continued to establish himself as a formidable and respected warrior. Before he was 20 years old he had been in 19 battles and had been wounded six times. His most serious wound occurred during a winter raid upon the Shoshoni Indians; he was shot in the back and the lead ball was never removed. In later years this wound made it difficult for him to ride horses or to travel long distances. Crowfoot seldom went to war after he reached manhood. Instead, he became involved with raising horses, which made him wealthy, and in the affairs of the tribe. In 1865, with the death of the chief of his band, No-okskatos (Three Suns), Crowfoot became a minor chief of the Blackfoot tribe, leading a band of about 21 lodges. At first his followers were known as the Big Pipes band but later were renamed the Moccasin band.

It was in 1865 also that Crowfoot first came to the attention of the local white population after his dramatic role in a battle at Three Ponds, which occurred just east of the present village of Hobbema, Alta. Father Albert Lacombe*, an Oblate missionary, was visiting a Blackfoot camp there when it was attacked by Crees. Although greatly outnumbered and despite casualties, the Blackfeet held off the raiders for several hours during the night. Just before dawn Father Lacombe tried to get between the lines to call a truce, but he was not recognized by the Crees and was wounded by a ricocheting bullet. When the battle seemed lost, Crowfoot arrived with a large number of warriors and the enemy was soon routed.

Crowfoot, as a minor chief, tried to establish friendly relations with white fur-traders and missionaries. Late in 1866 he prevented a number of Blackfoot warriors from looting a train of Hudson’s Bay Company carts and killing its Métis drivers. Then, defying a number of warrior chiefs, he provided a safe escort for the Métis back to Fort Edmonton. He also became a good friend of HBC trader Richard Charles Hardisty who was in charge of Rocky Mountain House.

In the smallpox epidemic of 1869–70 several Blackfoot leaders died and Crowfoot emerged as one of the three head chiefs of the tribe. In 1872, with the death of Akamih-kayi (Big Swan), the leadership was reduced to Crowfoot and Natosapi (Old Sun), an elderly warrior chief.

In 1873 Crowfoot’s eldest son was killed in a raid on a Cree camp, and the chief led a large revenge party which succeeded in killing an enemy warrior. This was Crowfoot’s last warlike deed. Some months later during a temporary peace treaty between the Blackfeet and Crees, Crowfoot met a Cree who bore a startling resemblance to his dead son. He adopted the man, who was known to the Crees as Poundmaker [Pītikwahanapiwīyin], and gave him his dead son’s name, Makoyi-koh-kin (Wolf Thin Legs). Poundmaker returned to the Crees where he became a chief, but he remained close friends with Crowfoot for the rest of his life.

During the 1870s American traders were invading the Canadian west selling whisky and repeating rifles to the Indians. As a result, hundreds of Indians were dying from the liquor and the intertribal warfare it precipitated. When Crowfoot was informed in 1874 that the North-West Mounted Police were being organized and were coming to his hunting grounds he welcomed the police as a needed solution to a serious problem. He told the Reverend John Chantler McDougall*: “If left to ourselves we are gone. The whiskey brought among us by the Traders is fast killing us off and we are powerless before the evil. . . . Our horses, Buffalo robes and other articles of trade go for whiskey, a large number of our people have killed one another and perished in various ways under the influence, and now that we hear of our Great Mother sending her soldiers into our country for our good we are glad.”

In December 1874 Crowfoot first met James Farquharson Macleod*, assistant commissioner of the NWMP, and the two became friends. It was largely through their influence that white settlement in Blackfoot territory occurred without violence. Macleod insisted that Blackfoot rights be respected, while Crowfoot encouraged his people to maintain friendly relations with the police. Although he was actually one of two head chiefs of the Blackfoot tribe, the police considered him to be the leader of the entire Blackfoot nation. In fact, the Bloods were a larger tribe than the Blackfeet and all three tribes in the confederacy had independent leadership, but the confusion between “Blackfoot tribe” and “Blackfoot nation” – which included the Blood, Piegan, and Blackfoot tribes and their allies the Sarcees and the Gros Ventres – as well as Crowfoot’s impressive role as diplomat and politician, often caused whites to place him in a position that he did not in fact occupy. Crowfoot, for his part, was careful to consult his fellow chiefs in such situations.

In 1876, when the wars were raging in the United States between the Plains Indians and the American cavalry, a Sioux messenger came to Crowfoot’s camp asking the Blackfeet to join the fight. After the Sioux had defeated the Americans, the messenger said, they would help the Blackfeet exterminate the NWMP. Crowfoot not only rejected the offer but said he would join the police to fight the Sioux if they ever came north. (News of Crowfoot’s stand was forwarded to Ottawa and eventually to England where Queen Victoria praised the chief for his loyalty.) A short time later, when the Sioux fled to Canada after the battle at Little Bighorn River (Mont.), Crowfoot realized they came as refugees. He met Sitting Bull [Ta-tanka I-yotank] during the chief’s exile in Canada, and when he learned that Sitting Bull’s tribe sought peace with the Blackfeet he was pleased to accept the chief’s offer of tobacco. The great Sioux leader was so impressed that he named his own son Crowfoot.

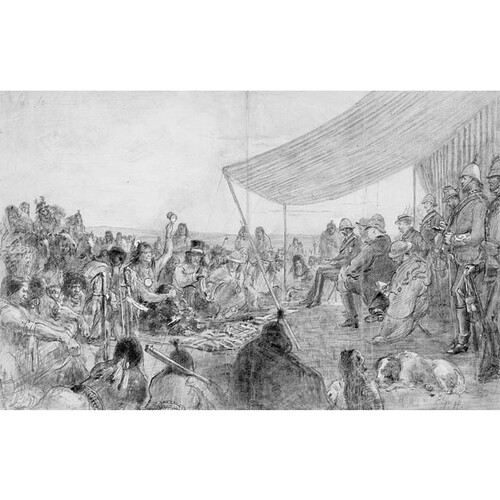

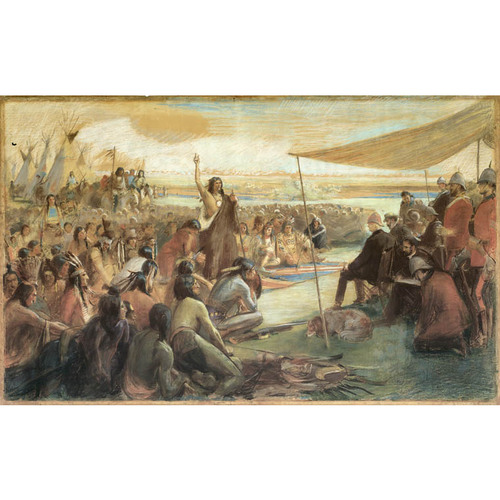

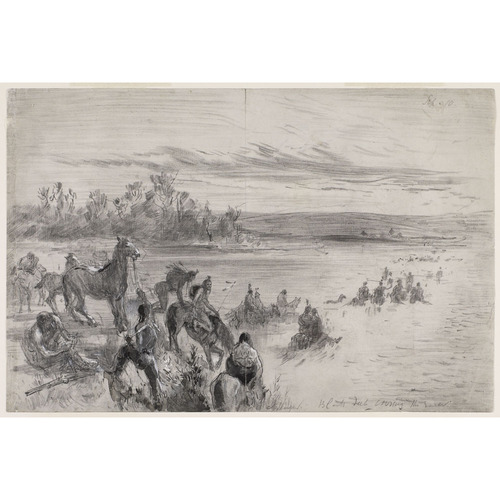

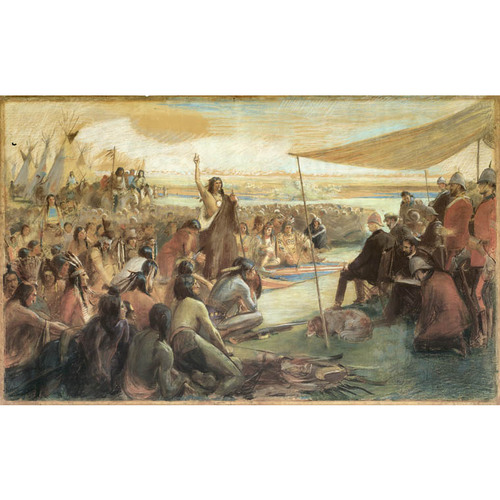

In 1877 David Laird*, the new lieutenant governor of the North-West Territories, invited the Blackfoot, Blood, Piegan, Sarcee, and Stony tribes to negotiate Treaty no.7 with the Canadian government. These tribes included those living in what is now southern Alberta south of the Red Deer River, and no.7 was the last of the treaties to be negotiated by the Canadian authorities in the 1870s in a programme to obtain the surrender of all Indian claims to the western Canadian prairies. At the outset an argument arose as to a meeting-place for the negotiations, the Bloods and Piegans preferring Fort Macleod and Crowfoot insisting on Blackfoot Crossing in the centre of his own domain away from any of the white man’s forts. The government acceded to Crowfoot’s demands, but the leading chiefs of the Blood and Piegan tribes threatened not to attend. Negotiations began on 16 September with Crowfoot as the principal chief in attendance, and for the next four days he led the discussions. When the Bloods and Piegans finally arrived they joined Crowfoot in an all-night session to receive his account of the treaty and his recommendations. By dawn, all the leading chiefs had agreed to the terms of the treaty and, because of Crowfoot’s role during the negotiations and his favourable attitude towards the pact, he was asked to respond for the entire Blackfoot nation: “While I speak, be kind and patient. I have to speak for my people, who are numerous, and who rely upon me to follow that course which in the future will tend to their good. The plains are large and wide. We are the children of the plains, it is our home, and the buffalo has been our food always. I hope you look upon the Blackfeet, Bloods and Sarcees as your children now, and that you will be indulgent and charitable to them. . . . The advice given me and my people has proved to be very good. If the Police had not come to the country, where would we be all now? Bad men and whiskey were killing us so fast that very few, indeed, of us would have been left to-day. The Police have protected us as the feathers of the bird protect it from the frosts of winter. I wish them all good, and trust that all our hearts will increase in goodness from this time forward. I am satisfied. I will sign the treaty.”

Shortly after taking treaty, many Indians began to doubt the wisdom of their actions. The deaths of three prominent chiefs, the destruction of extensive grazing lands by prairie fires, and the disappearance of the buffalo were considered to be ill omens. By summer 1879 hunting was so poor that many Blackfeet were starving and were forced to follow the last buffalo herds into the United States. Crowfoot took his tribe into Montana where, without the presence of the NWMP, they were again subjected to the problems of whisky pedlars, horse thieves, and intertribal warfare. During this time the Blackfoot treaty with the Sioux ended – with a horse raid on Crowfoot’s camp. To add to the unsettled conditions, Louis Riel and his followers spent a winter camped by the Blackfeet, attempting to spread discontent. As the buffalo herd was destroyed, the Blackfeet faced starvation, and in 1881 hunger forced the tribe to return to Canada.

Upon his return Crowfoot learned that the government agency responsible for his people had changed from the NWMP to the newly established Department of Indian Affairs. Over the next months he found the new administrators to be callous in their treatment of the Indians. Angry and disillusioned, he openly defied the police for the first time early in 1882 when they tried to arrest a minor chief of the Blackfoot tribe. Crowfoot was becoming distrustful of the government and the NWMP, and when Cree and Métis agitators began to visit his camp, he learned that his problems were shared throughout the west.

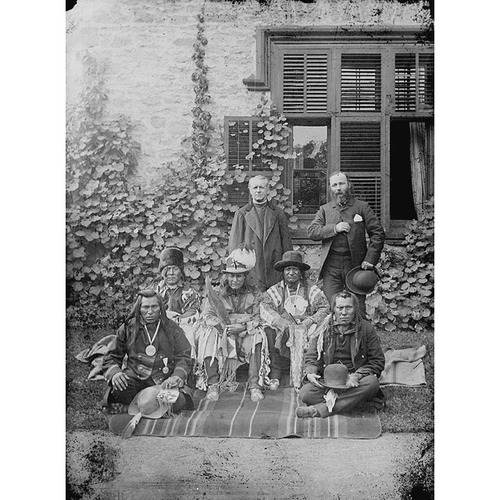

In 1884, after one of Riel’s followers had been arrested in the Blackfoot camp, the Indian commissioner, Edgar Dewdney*, invited Crowfoot and other Blackfoot chiefs to visit Regina and Winnipeg. As the commissioner had hoped, the visit to the large white settlements shattered the Indians’ belief that they were more numerous than the whites. This knowledge had a great impact upon Crowfoot’s behaviour during the North-West Rebellion of 1885. Undoubtedly his sympathies were with the Crees, led by Big Bear [Mistahimaskwa] and Crowfoot’s own adopted son, Poundmaker, but he believed they could not win. In addition, neither the Piegans nor the Bloods would support their hereditary enemy, the Crees, and the Blood tribe even offered to send warriors to fight for the government. Actually, for the first several days of the rebellion, Crowfoot was non-committal, both to rebel runners who visited his camp and to government officials. Only after he had ascertained the continued hostility of the Bloods and Piegans, as well as hearing promises of the government, did he finally pledge his loyalty to the crown.

Nevertheless, considerable alarm was expressed during the rebellion regarding the loyalty of the Blackfoot nation. At one point, Calgary inhabitants feared they would be attacked, and Father Lacombe was sent to Crowfoot’s camp to investigate. He was told by Crowfoot that in spite of frequent messages from the Crees and the fact that Poundmaker was in the centre of the conflict, the Blackfeet did not intend to rise. When this news was transmitted to Ottawa, the governor general, Lord Lansdowne [Petty-Fitzmaurice*], expressed his thanks to Crowfoot on behalf of the queen, and the cabinet of Sir John A. Macdonald* gave the Blackfoot chief a round of applause. In the following year Crowfoot and his foster brother No-okska-stumik (Three Bulls) were taken on a tour of Montreal and Quebec by Father Lacombe in recognition of their loyalty. Crowfoot was lionized by the press and public, his tall stately appearance and classic Indian features fulfilling everyone’s romantic image of “the noble Indian.” On his return from Quebec, Crowfoot stopped in Ottawa where he met Macdonald and gave him the Indian name for “Brother-in-Law.”

Although Crowfoot had become a notable Canadian figure, he was an unhappy man during the last decade of his life. He was increasingly disillusioned about the treatment of his people by government employees and officials, his own health was deteriorating, and his personal life was struck by a series of tragedies. Crowfoot had a total of ten wives during his lifetime – usually three or four at one time – his favourite wife being Sisoyaki (Cutting Woman). She accompanied him on trips to other reserves and occupied the honoured place beside him in his teepee. But in spite of the large number of wives, only four of Crowfoot’s children ever reached maturity. In a tribe where boys were highly favoured, Crowfoot had only one blind son, Kyi-i-staah (Bear Ghost), and three daughters who survived their childhood years. Many of the others died of tuberculosis. To add to his grief, his adopted son Poundmaker was sent to prison for his part in the rebellion; released in 1886 as a favour to Crowfoot, he died suddenly in Crowfoot’s camp only four months later.

The last three years of Crowfoot’s life were spent quietly, visiting old friends on neighbouring reserves. In 1887 he assisted Red Crow [Mekaisto*], head chief of the Bloods, in preventing his warriors from raiding the Gros Ventre Indians, and in the following year he travelled to Montana where he tried unsuccessfully to arrange a peace treaty with the Assiniboins. Ill and with failing eyesight, Crowfoot remained on his reserve during the winter of 1889–90, and died during the spring. His chieftainship was assumed by his foster brother, Three Bulls, but neither he nor succeeding chiefs achieved the prestige or greatness of Crowfoot.

Can., Parl., Sessional papers, 1876, VII, no.9: 23–24. Morris, Treaties of Canada with the Indians. Macleod Gazette and Alberta Livestock Record (Fort Macleod), 22, 29 May 1890. H. A. Dempsey, Crowfoot, chief of the Blackfeet (Edmonton, 1972). C. E. Denny, The riders of the plains: a reminiscence of the early and exciting days in the north west (Calgary, 1905). Katherine Hughes, Father Lacombe, the black-robe voyageur (Toronto, 1911). J. [C.] McDougall, On western trails in the early seventies; frontier pioneer life in the Canadian north-west (Toronto, 1911).

Cite This Article

Hugh A. Dempsey, “ISAPO-MUXIKA (Crowfoot, Pied de Corbeau),” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 11, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed December 30, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/isapo_muxika_11E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/isapo_muxika_11E.html |

| Author of Article: | Hugh A. Dempsey |

| Title of Article: | ISAPO-MUXIKA (Crowfoot, Pied de Corbeau) |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 11 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1982 |

| Year of revision: | 1982 |

| Access Date: | December 30, 2025 |