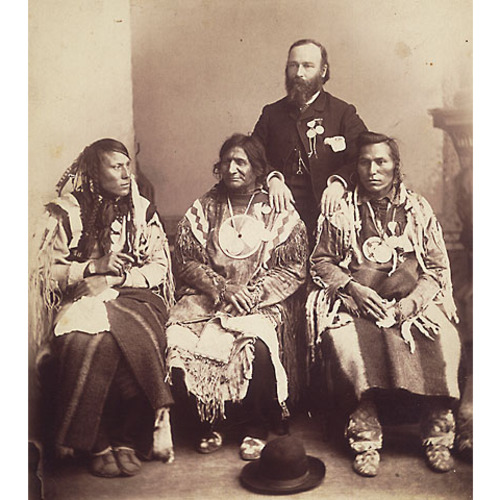

MÉKAISTO (Red Crow, also known as Captured the Gun Inside, Lately Gone, Sitting White Buffalo, and John Mikahestow), Blood Indian warrior and chief, farmer, and jp; b. c. 1830 at the confluence of the St Mary and Oldman rivers (Alta), son of Kyiyo-siksinum (Black Bear) and Handsome Woman; d. 28 Aug. 1900 on the Blood Indian Reserve (Alta).

Red Crow was born to a long line of chiefs in the Blood tribe of the Blackfoot confederacy, including his grandfather Stoo-kya-tosi (Two Suns), leader of the Mamyowi (Fish Eaters band) at the time of Red Crow’s birth, his uncle Seen From Afar [Peenaquim*] who succeeded Two Suns, and his father Black Bear. In his early teens Red Crow began to go to war and during his lifetime established an impressive war record of 33 raids against Crow, Plains Cree, Assiniboin, Shoshoni, and Nez Percé camps, killing five enemies. He also likely participated in an attack organized in April 1865 by his father-in-law Calf Shirt [Onistah-sokaksin*] against American settlers on the Missouri River, which sparked the Blackfoot war that lasted until 1870. Late in life Red Crow was able to boast, “I was never struck by an enemy in my life, with bullet, arrow, axe, spear or knife.”

Leadership of the Fish Eaters band was assumed by Red Crow’s father when Seen From Afar died of smallpox in 1869 during an epidemic that decimated the Bloods and other tribes in the Blackfoot confederacy. Only a few weeks later he too succumbed to smallpox, and the band chose Red Crow as their new chief. During these years American traders were flooding Blackfoot country on both sides of the international boundary with whisky. The discord and bloodshed that resulted had tragic repercussions in Red Crow’s own life. He killed his brother Kit Fox during a drinking bout, slew two drunken Indians who attacked him, and saw his principal wife, Ohkipiksew (Water Bird), killed by a stray bullet during one of these quarrels. The shock of these troubles turned him from a reckless warrior into a strong but conservative leader.

Because of the troubles Red Crow was pleased to see the arrival of the North-West Mounted Police. In November 1874 he met with NWMP assistant commissioner James Farquharson Macleod and three years later the bond of friendship and trust that quickly formed between the two men played a large part in Red Crow’s acceptance of Treaty No.7, with Crowfoot [Isapo-muxika*] and other native leaders of present-day southern Alberta. An astute politician, Red Crow then centralized the control of several bands and became the leading head chief of the Bloods.

The depletion of the northern buffalo herd was accelerated in this period by American hunters in the Montana Territory who slaughtered tens of thousands of animals for their hides. During the winter of 1879–80 Red Crow accepted the awful truth: the buffalo had been destroyed and the Bloods would need to start a new life. In September 1880 he selected the site of the Blood reserve, on the Belly River near the mouth of the Waterton River. While other chiefs, such as Natose-Onista (Medicine Calf or Button Chief) and Crowfoot, clung desperately to their old ways despite dwindling buffalo herds, horse thieves, and whisky traders, Red Crow realized that the traditional nomadic life-style was ending, and by November he had settled into log shanties on the new reserve with his following of 62 families.

Red Crow and his family began growing vegetables and grain in small garden plots, and by 1884 their 582-acre farm was the largest on the reserve. In 1890 Red Crow’s eldest son, Nina-kisoom (Chief Moon), purchased a used mower and began competing with white men for haying contracts with the Indian Department, local ranchers, and the NWMP. In 1894 cattle ranching was introduced; Red Crow and an adopted son, Makoyi-Opistoki*, each exchanged some of their prized horses for 15 head of cattle, while another relative took 10. By 1900 Red Crow’s herd had grown to more than 100 and the cattle population for the reserve had risen to 2,000.

The transition to reserve life for the Bloods had not been without difficulty. In 1883 a government economy drive directed by Lawrence Vankoughnet, the deputy superintendent general of Indian affairs, resulted in reductions in rations on the Blood reserve and staff cuts among the government employees serving the reserve. The following year bacon, a meat unknown to the Bloods, was substituted for freshly killed beef in the Indians’ rations. Only after demonstrations of discontent by Red Crow and other Blood chiefs, notably White Calf [Onista’poka], and a meeting with Lieutenant Governor Edgar Dewdney* in Regina was the order to issue bacon withdrawn. Red Crow was a dynamic leader who maintained control over the Bloods during a period in which other Indians were often caught killing cattle from nearby ranches to supplement government rations. Through the warrior police and his actions as magistrate, he resolved problems on the reserve, but in doing so he frequently became embroiled in controversy with the Indian agents who tried to place all authority in the hands of the government.

At the outbreak of the North-West rebellion in 1885, government authorities feared that the Bloods might join the Métis and Cree insurgents [see Louis Riel*; Pītikwahanapiwīyin*]. Red Crow, however, had always considered both the Cree and the Métis to be enemies and adamantly rejected any suggestion of participation. In 1886 he and Crowfoot were members of a delegation of Blackfoot chiefs taken on a tour of eastern Canada as an expression of Prime Minister Sir John A. Macdonald’s thanks for their loyalty. Red Crow visited the Mohawk Institute (Woodland Indian Cultural Centre) near Brantford, Ont., and was so impressed with the progress of Indian students there that he returned to the Blood reserve a strong proponent of education for his people. He supported Anglican, Methodist, and Roman Catholic missionaries in their efforts to provide schooling, and in later years he sent an adopted son, Astohkomi (Shot Close, Frank Red Crow), to St Joseph’s Industrial School at Dunbow, south of Calgary.

Although he favoured Catholics because their mission house was in his camp, Red Crow preferred to remain with his native religion. The last years of his life were spent battling with Indian agent James Wilson for religious freedom on the reserve. He resisted Wilson’s attempts to halt medicine pipe dances and succeeded in having the Sun Dance restored in 1900 after Wilson’s suppression of that ceremony since 1895. Interestingly enough in December 1896 Red Crow had been baptized a Catholic and legally married in the church to his youngest wife, Singing Before (Frances Ikaenikiakew), despite the fact that he had a personal household which included three other wives. According to Wilson, Red Crow did so at his young bride’s insistence; she wanted a legal marriage so that her son, Shot Close, would inherit the estate. A few weeks after the 1900 Sun Dance, Red Crow died quietly on the banks of the Belly River while gathering in his horses.

A warrior at heart, Red Crow had not accepted dependence upon the government and had encouraged farming, ranching, and education as means for his people to become self-sufficient. He instilled within the Bloods an independence and pride which made them subservient to no one, not even the white man. His position of leadership among the Bloods was taken by Makoyi-Opistoki and remained within the family until 1980.

A detailed bibliography is given in H. A. Dempsey, Red Crow, warrior chief (Saskatoon, 1980).

Cite This Article

Hugh A. Dempsey, “MÉKAISTO (Red Crow, Captured the Gun Inside, Lately Gone, Sitting White Buffalo, John Mikahestow),” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 12, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed December 31, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/mekaisto_12E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/mekaisto_12E.html |

| Author of Article: | Hugh A. Dempsey |

| Title of Article: | MÉKAISTO (Red Crow, Captured the Gun Inside, Lately Gone, Sitting White Buffalo, John Mikahestow) |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 12 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1990 |

| Year of revision: | 1990 |

| Access Date: | December 31, 2025 |