Source: Link

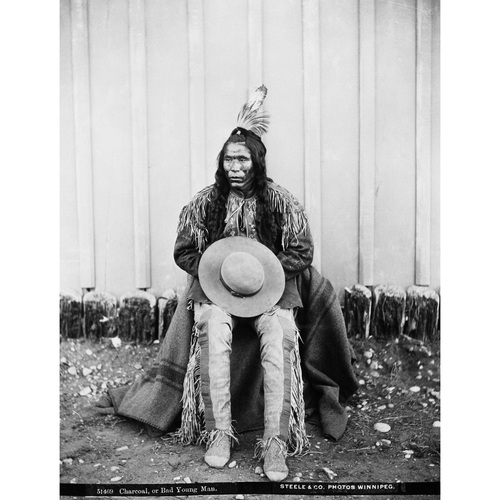

SI’K-OKSKITSIS (Charcoal, or literally Black Wood Ashes; also known as Paka’panikapi, Lazy Young Man, and Opee-o’wun, The Palate), Blood Indian warrior and holy man; b. c. 1856 in what is now southern Alberta, son of Red Plume and Killed Twice; d. 16 March 1897 by hanging at Fort Macleod (Alta).

Charcoal, born to a large family, was related through one of his father’s wives to Seen From Afar [Peenaquim*], the warrior chief of the Mamyowi (Fish Eaters band). When he was still young, his family broke from the Fish Eaters, then led by Red Crow [Mékaisto], to form a band of their own. This band, which had a poor reputation within the tribe and was accused of indolence and troublemaking, was called the Uspoki-omiks (Shooting Up band). Charcoal did not adjust well to settled life on the Blood Indian Reserve (Alta), established in 1880, and was arrested in 1883 for killing a steer belonging to a nearby rancher. For this crime he spent a year in the North-West Mounted Police jail at Fort Macleod and after his release he vowed he would never be put behind bars again.

With no more battles or raids in which to participate now that the Bloods had given up their traditional nomadic, hunting life-style for the reserve, Charcoal turned to native religion, joining the sacred Dog Society and later the Horn Society. In addition he encouraged his fourth wife, Anu’tsis-tsis-aki (Pretty Wolverine Woman), to participate in the Motokix, the only secret society for women on the Blood reserve. By the mid 1890s she had become one of the leaders of the society and Charcoal was recognized as a holy man.

Soon after taking another wife, Iyokaki (Sleeping Woman), in 1896, Charcoal learned that Pretty Wolverine Woman was having an affair with one of her young cousins named Nina’msko’taput-sikumi (Medicine Pipe Man Returning with a Crane War Whoop). On 30 September he found them together and killed the Lothario by shooting him through the eye. Reservation life and the white man’s rules had been forgotten and Charcoal had returned to the traditional ways of his forefathers. Having killed, however, he believed that his life was over and that he would be hanged for his crime. To prepare for his entry into the land of the dead he reverted to two ancient customs of the Blood Indians: he decided to kill an important person whose spirit would announce his coming, and then kill Pretty Wolverine Woman and himself so that their spirits would travel together and she would eternally be his slave.

On the day Medicine Pipe Man’s body was found, 12 October, Charcoal attempted to kill Red Crow and then shot and wounded a farm instructor, Edward McNeill. He fled the reserve, with two wives, a daughter, a mother-in-law, and two stepsons, going south to Lee Creek (Alta) and then to the Blood Indian timber limit near the Montana border. In the mean time one of the biggest man-hunts in western Canadian history was being organized by NWMP superintendent Samuel Benfield Steele*. Concern in the Canadian and American press about the NWMP’s ability to handle Indian problems was already running high because of the successful flight of Almighty Voice [Kitchi-Manito-Waya] after he killed a police sergeant in 1895. Charcoal’s camp was discovered but, when a force of more than 24 armed men attacked on 17 October, he escaped on foot with his wives and a stepson; that evening he stole two NWMP horses and fled north toward the Porcupine Hills. By the next day the search party had grown to more than 100 mounted police and Indian scouts, but Charcoal continued to elude police patrols, travelling long distances and stealing fresh horses when his mounts were worn out. On 30 October, by which time his stepson and both wives had escaped from Charcoal, Steele had his entire family, 26 people including 2 children, aged 5 and 1, arrested to keep them from aiding him. Two of Charcoal’s brothers, Left Hand and Bear Back Bone, were released on 5 November to help capture the fugitive. In exchange for their cooperation, Steele allowed the release of Left Hand’s sick child and dropped charges of cattle-stealing against the son of Bear Back Bone.

Travelling between the Peigan Indian Reserve (Alta) and the Blood reserve, Charcoal continued to thwart the NWMP attempts to entrap him. On 9 November police picked up his trail near the Peigan reserve and the following day he was sighted by a patrol of Peigan scouts near Pincher Creek. Sergeant William Brock Wilde of the NWMP joined the pursuit and when he closed on Charcoal was shot and killed. The following night Charcoal arrived at his brothers’ camp on the Blood reserve where he was captured in the early morning of 12 November and turned over to the NWMP after an unsuccessful suicide attempt.

Charcoal was tried and convicted at Fort Macleod for the murder of Medicine Pipe Man and Wilde. Although the first conviction was successfully appealed, the second was upheld and Charcoal was hanged on the morning of 16 March 1897. Despite assurances from Lieutenant-Governor Charles Herbert Mackintosh* that the body would be turned over to his family for an Indian burial, Charcoal had been claimed as an eleventh-hour convert to Christianity and he was buried in the Roman Catholic cemetery at Stand Off (Alta) on the Blood reserve.

A full bibliography is given in H. A. Dempsey, Charcoal’s world (Saskatoon, 1978).

Cite This Article

Hugh A. Dempsey, “SI’K-OKSKITSIS (Charcoal, Black Wood Ashes) (Paka’panikapi (Lazy Young Man), Opee-o’wun (The Palate)),” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 12, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed December 31, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/si_k_okskitsis_12E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/si_k_okskitsis_12E.html |

| Author of Article: | Hugh A. Dempsey |

| Title of Article: | SI’K-OKSKITSIS (Charcoal, Black Wood Ashes) (Paka’panikapi (Lazy Young Man), Opee-o’wun (The Palate)) |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 12 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1990 |

| Year of revision: | 1990 |

| Access Date: | December 31, 2025 |