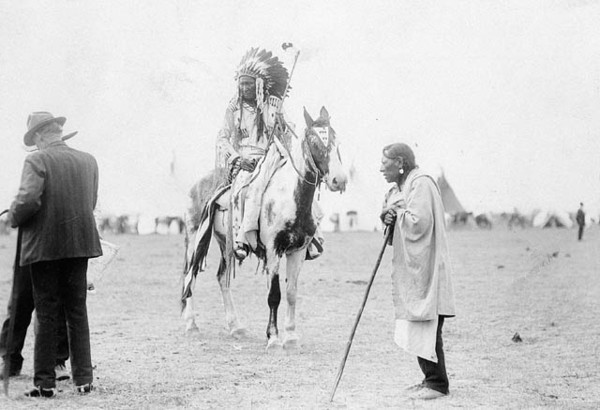

MAKOYI-OPISTOKI (Crop Eared Wolf), Blood Indian warrior, the leader of the Fish Eaters band, and the head chief of the tribe; b. c. 1845 in what is now southern Alberta, son of Natos-api (Sun Old Man); m. Paynot-sinimatsaki (Coup in Sight), Sakoy-inamuhka (Took the Gun Last), Stamiksitsaki (Bull Gut Woman), and Nitohksini (One Bone); d. 14 April 1913 on the Blood Indian Reserve, Alta.

Crop Eared Wolf was born in the Many Children band, but in the 1850s, when both his parents died, he was adopted by Red Crow [Mékaisto*] and transferred to the Fish Eaters band. His sister had married Red Crow a few years earlier and had prevailed upon her husband to take the orphaned boy. Within a short time Crop Eared Wolf became the chief’s favourite child, receiving preference over his others. Both Red Crow and Crop Eared Wolf were of a similar nature – highly intelligent, fearless in battle, and astute in politics. They also looked alike, being fairly short and not handsome.

During his lifetime, Crop Eared Wolf took part in several major forays against enemy tribes. The fight that had the greatest permanent effect on him occurred in 1865 when he accompanied his foster father on a raid against the Cree. The expedition was organized in revenge for a Cree attack in which a Sarcee chief had been killed. The Cree succeeded in shooting Crop Eared Wolf in the leg, and he walked with a limp for the rest of his life. The wound virtually ended his career as a raider, so he turned his attention to horse breeding. By the time the Blood settled on their reserve at the Belly River in 1880, he had become a wealthy man, possessing a large horse herd. In the 1890s, for example, he paid 100 horses to become the owner of the long-time medicine pipe – one of the most sacred objects on the reserve.

During the first two decades on their reserve, Crop Eared Wolf was in the shadow of his more famous foster father. They both turned to farming and in 1884 they shared the largest farm, with 58 1/2 acres planted in potatoes and grain. The harvest of vegetables was stored in root houses and shared with members of the band over the long winter months. In 1894 Crop Eared Wolf was one of the first four men to begin raising cattle. He and Red Crow exchanged 15 horses for a similar number of cattle. By the end of the century the Blood had a prosperous ranching industry, with individuals owning 2,000 head.

Before the death of Red Crow on 28 Aug. 1900, the chief indicated that he wished Crop Eared Wolf to succeed him, in spite of the fact that his son Willie Red Crow openly campaigned for the position. Red Crow saw in his adopted son a stability and quiet, forceful leadership which he knew would be essential for the success of the tribe. The choice was wise, for in the next few years the Blood were assailed with demands that they surrender parts of their reserve for use by white settlers. The first attempts were made in 1901 when residents of Cardston [see Charles Ora Card*] wanted land thrown open for settlement. In 1907 the tribe was forced to vote on the proposition of selling 2,400 acres near their southern boundary. Although the government put pressure on the Indians to agree, the surrender was rejected by a vote of 109 to 33. An irate local newspaper commented that Crop Eared Wolf “personally canvassed every vote on the reserve. Some he scared, others he coaxed, and others he induced to stay away, and he converted a sweeping sentiment in favor of settling into a triumphant majority against.”

In retaliation, Indian agent Robert Nathanial Wilson set out to humiliate the chief at every opportunity and tried to have him deposed. Crop Eared Wolf responded by filing a formal complaint of harassment through local lawyers and appealing directly to Indian commissioner David Laird for support. Partly as a result of his action, the government abandoned any immediate plans to force further surrender votes and concentrated on breaking land for Indian farmers. Crop Eared Wolf strongly endorsed this program and by 1909 the Blood had cultivated almost 2,500 acres of land with their own steam tractor and had harvested 24,000 bushels of wheat with their own machinery.

By then, Crop Eared Wolf was a self-sufficient rancher. He sold a dozen or two cattle each year and owned a modern frame-house. As a local newspaperman commented: “He was stern with his people, but kind with the white man so long as nothing was said or done to interfere with the Indian or his rights. He was a most careful guardian of Indian rights.” At his death in 1913, the Blood were a prosperous and self-reliant people. However, the chief was always worried about future attempts to deprive them of their lands. “It is said,” reported the Calgary Daily Herald, “that one of the last things Crop Eared Wolf did before his death was to call his minor chiefs and people together and make them promise that they would never sell their land to the white man.” He then designated his son, Shot Both Sides, to be his successor and to resist any future threats to the land. Although further attempts were made to reduce the size of the reserve in 1917, 1918, 1920, and 1921, no Blood lands were ever voluntarily surrendered.

GA, M4421. Calgary Herald, 21 Nov. 1901, 22 April 1913. Lethbridge Herald (Lethbridge, Alta), 21 April 1913. Macleod Gazette (Fort Macleod, Alta), 13 June 1907. Winnipeg Tribune, 12 Aug. 1913. H. A. Dempsey, Red Crow, warrior chief (Saskatoon, 1980).

Cite This Article

Hugh A. Dempsey, “MAKOYI-OPISTOKI (Crop Eared Wolf),” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 14, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed December 31, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/makoyi_opistoki_14E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/makoyi_opistoki_14E.html |

| Author of Article: | Hugh A. Dempsey |

| Title of Article: | MAKOYI-OPISTOKI (Crop Eared Wolf) |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 14 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1998 |

| Year of revision: | 1998 |

| Access Date: | December 31, 2025 |