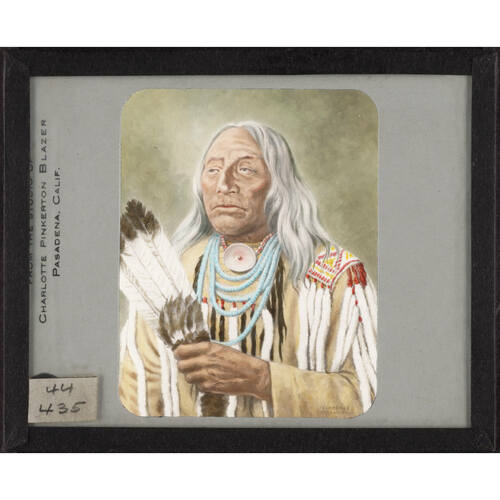

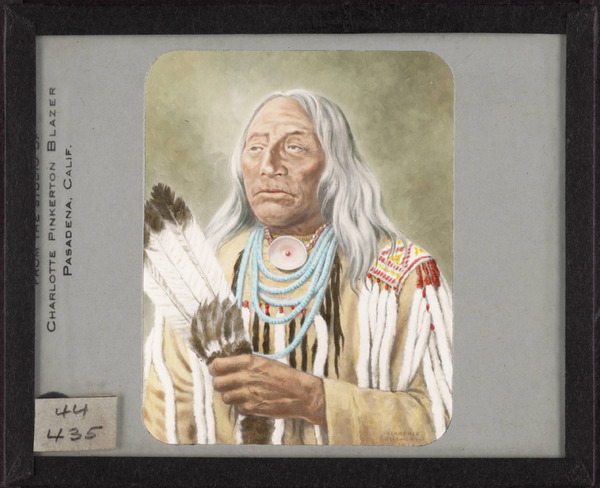

Source: Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

ONISTA’POKA (White Calf, also known as Father of Many Children (Manisto’kos) and Running Crane (Siki’muka)), Blood Indian war chief; b. c. 1838 probably in what is now southern Alberta; he had two wives, and they had several children; d. 19 Aug. 1897 on the Blood Indian Reserve (Alta).

White Calf was born into the Buffalo Followers band of Blood Indians. He gained a favourable war record and by the time the North-West Mounted Police came west in 1874 he was recognized as a war chief and had formed his own band, the Marrows. In 1877 he was one of the signatories of Treaty No. 7 [see Isapo-muxika*], with a following of 107 persons. Before the Bloods settled on their reserve in 1880, Red Crow [Mékaisto] was the leading political chief of the tribe and Natose-Onistors (Medicine Calf) the leading war chief. However, in 1881 the latter was deposed and White Calf assumed his position, thus becoming Red Crow’s main political opponent. A year later he led a war party of more than 200 Bloods against the Plains Cree camp of Piapot [Payipwat*] in the Cypress Hills (Sask.); before the NWMP could intercede, a Cree was killed and scalped.

White Calf came into conflict with government authorities several times in the 1880s and was seen by a succession of Indian agents as “a great talker and no worker” and the “Prince of grumblers,” to cite the views of one of them, William Pocklington. Riding a crest of popularity, he was a candidate for a head chieftainship of the tribe in 1883, which would have made him equal to Red Crow. Indian agent Cecil Edward Denny, however, arranged for the selection of White Calf’s brother-in-law, Calf Tail, instead. In 1884 White Calf, Red Crow, and other Blood chiefs forcefully opposed an attempt to substitute bacon for government beef rations. White Calf later protested against the setting of the reserve boundaries and against a peace treaty with the Gros Ventres and Assiniboin Indians. In March 1885, when he failed in an appeal to the NWMP to have his son Never Ties His Shoes (also known as Oral Talker) released following his arrest for horse-stealing, White Calf threatened to let the young men of his band “turn loose.” Red Crow intervened to calm the situation and Never Ties His Shoes was acquitted shortly afterward.

When the North-West rebellion [see Louis Riel*] erupted later the same month, government officials expressed fears that White Calf might join the insurgents. But, like most Bloods, he hated the rebellious Crees [see Mistahimaskwa*; Pītikwahanapiwīyin*] more than he did white men. He assured interpreter Jerry Potts that they would have nothing to do with the Crees. After the rebellion, when Governor General Lord Lansdowne [Petty-Fitzmaurice*] visited the Blood reserve in the fall of 1885, White Calf was positive in his remarks. This did not prevent a serious confrontation with Pocklington. After the death that summer of Father of Many Children, chief of the Buffalo Followers band, White Calf had taken his name and attempted to reorganize the Buffalo Followers, adding them to his own Marrows band. This manœuvre was rejected in November by Pocklington, who feared White Calf’s leadership and believed that an increase in his importance “would be the worst possible thing that could happen, for being very much gifted as a talker he would use his influence to put bad thoughts into the heads of the young men on the Reserve.” Understandably, White Calf was again at odds with Pocklington, calling the agent “and all the whites in the country dogs, liars, thieves and goodness knows what besides.”

The factious chief continued to be a dynamic and influential leader on the reserve until early 1891, when he moved with his band to the United States to join the South Piegans. However, a few months later he learned that Pocklington was being transferred and decided to return to the Blood reserve. He had difficulties with the new Indian agents, first Acheson Gosford Irvine and then from November 1892 James Wilson, and continued to oppose Red Crow. White Calf remained on the reserve, supporting native religion and traditional warlike practices, until his death in 1897.

In times when his people suffered from starvation and disease, White Calf’s efforts to improve their lot brought him face to face with officious Indian agents. As a warrior chief, he adopted a style of leadership that favoured confrontation over diplomacy and the record of his encounters with government officials is one of threats and demonstrations.

NA, RG 10, CII, 1552–53, 1558. [C. E. Denny], The riders of the plains: a reminiscence of the early and exciting days in the north west (Calgary, 1905). Morris, Treaties of Canada with the Indians. H. A. Dempsey, Red Crow, warrior chief (Saskatoon, 1980).

Cite This Article

Hugh A. Dempsey, “ONISTA’POKA (White Calf, Father of Many Children (Manisto’kos), Running Crane (Siki’muka)),” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 12, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed January 1, 2026, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/onista_poka_12E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/onista_poka_12E.html |

| Author of Article: | Hugh A. Dempsey |

| Title of Article: | ONISTA’POKA (White Calf, Father of Many Children (Manisto’kos), Running Crane (Siki’muka)) |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 12 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1990 |

| Year of revision: | 1990 |

| Access Date: | January 1, 2026 |