Source: Link

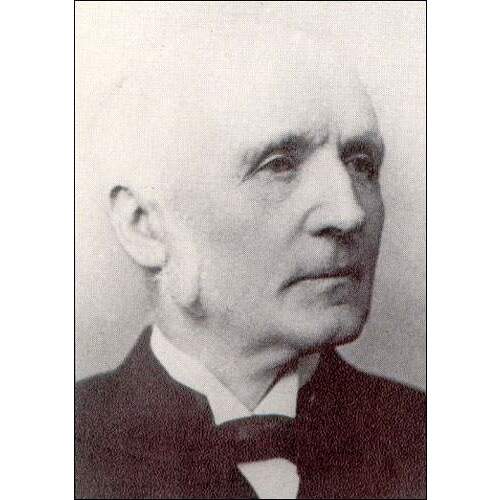

SHEA, Sir AMBROSE, newspaperman, businessman, politician, and governor of the Bahamas; baptized 15 May 1815 in St John’s, fifth son of Henry Shea* and Eleanor Ryan; m. first 24 June 1851 Isabella Nixon (d. 1877) in New York City; m. secondly 26 Nov. 1878 Louisa M. Hart, née Bouchette, in Quebec City; there were no children of either marriage; d. 30 July 1905 in London, England.

Ambrose Shea’s father, Henry, an immigrant from County Tipperary (Republic of Ireland) about 1784, founded one of the most talented and influential of 19th-century Newfoundland families. A respected merchant in St John’s, he could afford to provide his ten children with a decent education though he was of modest means, and it was presumably he who furnished the money to start the Newfoundlander newspaper, begun by his son John in 1827. On Henry’s death three years later John took over his father’s premises and trade, which he apparently gave up in 1836. The following year he moved permanently to Ireland, eventually to become the mayor of Cork. The Newfoundlander was taken over by his brothers William Richard* and Ambrose as joint proprietors. On William’s death in 1844, Ambrose became printer and publisher as well as editor, but in 1846 he moved away from journalism, the paper going to his younger brother, Edward Dalton*. It is likely that Ambrose had decided to concentrate on a business he started that year in partnership with James Murphy of Liverpool, England, as a shipbroker and commission merchant. The partnership ended, probably in bankruptcy, in 1848, and Shea subsequently launched his own, independent business. The same year he was elected to the House of Assembly as a member for Placentia–St Mary’s, having declined nomination in 1842. Thus began a political career that was to last 40 years.

Contemporaries recognized that Shea possessed considerable ability. He was intelligent, articulate, well informed, with what Daniel Woodley Prowse* described as a magnetic personality. All agreed that he was influential, for years a significant player on the political scene. Yet he never achieved high public office locally, a puzzling fact which demands explanation. It is important to remember that Shea was a native Newfoundlander and that he came from a family which espoused the older Irish tradition of cooperation with the British authorities. In the 1830s the Newfoundland Roman Catholic church, and the Liberal party which emerged after 1832, became dominated by immigrant Irishmen whose political attitudes were conditioned by the more aggressive nationalism of the period. Moreover, the party became closely allied with the ecclesiastical hierarchy. The Shea family had always opposed clerical interference in public life, and as editor of the Newfoundlander Ambrose had consistently promoted the interests of native Newfoundlanders regardless of denomination. He welcomed the foundation of the non-sectarian Newfoundland Natives’ Society in 1840, and he joined its management committee in 1842 and became president in 1846, in the face of fierce attacks on the society from “priests’ party” Catholics and from the priests themselves. His brother Dr Joseph Shea had in fact left the colony in 1837 as a result of such attacks. Therefore, though elected to the assembly as a Liberal, Ambrose stood apart from the mainstream of the party. He supported the O’Connellite agitation in Ireland and Newfoundland and other Liberal causes, such as the introduction of responsible government, but there was little chance of his becoming party leader. His identification was far more with fellow natives of a similar social class than with the network of immigrant Catholic families, headed by such figures as John Kent* and Patrick Morris*, that clustered around the Benevolent Irish Society, of which, significantly, Shea was not a member.

The Liberal party of the late 1840s was neither militant nor well organized. This situation gradually changed after 1850, when John Thomas Mullock* became Roman Catholic bishop, and Philip Francis Little* replaced Kent as leader. Shea at first refused to toe the party line on two issues: the subdivision of the Protestant education grant and the redistribution of seats under a future responsible government. But by 1852 he had closed ranks with the new leadership in the campaign for responsible government and had emerged as the Liberal spokesman on reciprocity with the United States. The Liberal party adopted “free trade” as one of its main causes – the largely mercantile Conservatives were on the whole opposed – and was concerned lest Newfoundland be overlooked in the treaty negotiations in Washington. In 1853, therefore, Shea went to Washington as the delegate of the Liberal-dominated assembly to press for the colony’s inclusion. His mission was successful, and it marks the beginning of his long identification with the idea that strong trade links with the United States would be of great benefit to Newfoundland.

The May 1855 election inaugurated responsible government, and Shea was returned on the party slate for St John’s West. When the assembly convened, he was elected speaker. Any bitterness over his exclusion from the Executive Council was mitigated when his brother Edward, one of the Ferryland members, was promoted in 1858. His omission may be explained in part by the demands of his business. Shea was never a wealthy man. He had neither partners nor sons and therefore was forced to devote a considerable amount of time to a firm that was expanding from the general trade of the colony into insurance and into acting as agent for the new transatlantic steamer service, which was inaugurated in 1859. In addition, Shea was active in the formation of the General Water Company, launched in January the same year to extend and improve the St John’s water system and fire brigade. He served as the company’s first president and again during the 1860s.

In July 1858 John Kent replaced Little as premier. Before long, serious tensions developed between the immigrant, pro-clerical wing of the Liberal party and the native wing, of which Shea was a prominent member. Moreover, there was a certain coolness between Shea and the new premier. It was publicized in February 1859, when Shea threatened to resign as speaker because Kent had not consulted him over a local appointment to an Anglo-French commission on the French Shore – a post which Kent took for himself. The premier found himself in the humiliating situation of having to move a resolution in the assembly asking Shea to stay on.

The Liberal government survived the 1859 election with an unchanged majority, but had had to face more challenges than in 1855. In partnership with the prominent Methodist James Johnstone Rogerson, Shea contested the marginal Burin district against the Conservative leader, Hugh William Hoyles*, and Edward Evans. It was a hard-fought battle long remembered in the colony, from which the Liberals emerged with a slim majority. Though such a famous victory must have given Shea a claim on a cabinet post, he stayed on as speaker, and apparently did little to patch up the divisions within the party. The 1860 session saw acrimonious exchanges between Shea, Kent, and the attorney general, George James Hogsett*, but what his precise role may have been in the collapse of the Kent government in February the following year is hard to assess. Though Shea was ill and absent from the assembly for much of the crucial period from December 1860 onwards, there were many who believed that, in spite of his brother’s presence in the cabinet, he was orchestrating the tactics of the anti-Kent forces. In any event, when Governor Sir Alexander Bannerman* dismissed the Kent ministry and installed Hoyles as leader of a minority government, Shea and Laurence O’Brien* were invited to join. The latter agreed, but Shea did not. It may have been, as one newspaper suggested, that Shea demanded three Catholic seats in the executive (as Bannerman wanted) and Hoyles was not prepared to grant more than two; or Shea may have anticipated a Liberal victory in the May 1861 election; or he may simply have decided to wait and see what emerged from the political crisis he had helped to create. The Liberals fought a disorganized campaign in the May election. Shea abandoned Burin to the Conservatives and retreated to Placentia. The party as a whole was narrowly defeated, and Shea found himself a leading member of a demoralized and bitter opposition.

In the summer of 1864 the mainland architects of confederation remembered Newfoundland’s existence and invited the Hoyles government to send representatives to the Quebec conference. Since the issue of union had not been debated in the colony, the government cautiously decided to send a bipartisan delegation without binding powers. Frederic Bowker Terrington Carter*, the speaker, represented Conservatives and Protestants; Shea, Liberals and Catholics. Both delegates became instant and enthusiastic confederates. They participated fully in the conference and signed “as individuals” the resolutions that resulted. At a dinner in Montreal Shea spoke glowingly of the mutual benefits to be expected as a result of confederation, and with Carter he signed a formal report warning that union could not be rejected “without aggravating the injurious consequences of our present isolation.”

In Newfoundland the Quebec resolutions were discussed extensively during the 1865 legislative session. Confederation proved to be an issue that cut across existing party lines, and in supporting union Shea once again set himself apart from most Liberals and most Catholics. Indeed, very few Catholics, and those members of the élite, were to support confederation. Not surprisingly therefore, when Carter became premier on Hoyles’s resignation in April 1865, the Shea brothers and John Kent (who also favoured union) joined the new government. All three became members of the executive, though Ambrose was without portfolio. In the election that fall he was again returned for Placentia.

Shea’s role as the chief Catholic spokesman for confederation, as well as his change of parties and his obvious influence in the administration, made him the object of a great deal of criticism and abuse. He was widely seen as an ambitious, greedy manipulator, “a political dodger and schemer,” the centre of a family compact that fattened off taxpayers and fishermen. Though respected for his abilities, Shea was mistrusted. Far more than Carter, who was generally popular, he became the lightning-rod for many anti-confederate attacks. This treatment did not alter his views, but it made virtually impossible his task of rallying Catholic opinion behind confederation. If anything, Catholic antipathy increased between 1864 and the 1869 election, in which union was the only issue. In an attempt to bolster the confederate cause, Shea made arrangements in 1869 for several hundred men to be employed on the Intercolonial Railway in the Maritime provinces. But not all found work, and men began to drift back home or elsewhere – many, indeed, never returned – with the result that Shea was subjected to a good deal of obloquy, and confederation was dealt a serious blow:

Their leader, sly Ambrose, beware of,

And keep his past conduct in view,

Remember his trick with the Navvies,

He’ll try the same treatment with you.

In Placentia district Shea and his colleagues faced a slate headed by Charles James Fox Bennett*, the leader of the anti-confederate party. The electorate was overwhelmingly hostile – at Placentia itself he was greeted by priest and people bearing pots of pitch and bags of feathers – and he was badly defeated. The confederate party, led by Carter, as a whole salvaged only nine seats.

Over the next few years Shea did not play a prominent part in public life. In 1873 he ran for the Conservatives in St John’s East. It was a heavily Catholic district and, being still viewed as an arch-confederate, he was defeated. However, a vacancy soon appeared at Harbour Grace, where he was returned without opposition in January 1874. In this predominately Protestant district, his return was allegedly (and quite possibly) courtesy of the Orange lodge, Orangemen having played an unusually active role in the 1873 election. Though the Bennett government had survived that contest, albeit with a reduced majority, it rapidly fell apart. In late January 1874 Carter resumed the premiership, and an election that fall gave him a working majority. Shea remained a member for Harbour Grace, the district he was to represent until 1885. Though not on the Executive Council, he was an influential and important member of the Conservative party. Both his brother and his brother-in-law William J. S. Donnelly were in the government, and it was alleged that he had considerable power over at least two other members of the executive, J. J. Rogerson and William Vallance Whiteway.

In line with attitudes he had frequently expressed in the past, Shea championed Newfoundland’s adoption of the fisheries clauses in the Treaty of Washington (1871), which provided for limited reciprocal trade with the United States. Equally consistently he supported efforts to diversify the colony’s economy, which in the 1870s centred around the scheme to build a trans-island railway. Shea had been the first to raise the matter in the assembly, proposing resolutions in favour of a railway in 1868. Like others who supported the line, he argued that it alone could bring about the economic stability that was needed to underpin political independence. Given Shea’s prominence – Canadian newspapers tended to identify him as the colony’s premier – it is at first sight surprising that he did not succeed Carter when the latter retired from politics in 1878. Instead Shea acquiesced in Whiteway’s succession to the premiership. The reason, probably, is that the Conservative party was not yet ready for a Catholic leader, particularly one with so long and controversial a history. In any event, there is truth in the frequently repeated criticism that Shea preferred to work behind the scenes; as the Terra Nova Advocate and Political Observer of St John’s acidly noted, he had little need to wear the feathers when he was already cock of the roost.

Shea was a member of the joint select committee that in 1880 recommended the construction of a railway from St John’s to Halls Bay, and he actively championed a tender submitted by Edmund W. Plunkett of Montreal. This position set him against Whiteway, who supported a tender from Albert L. Blackman of New York. The dispute raised the question of the railway’s gauge, since Plunkett was not prepared to build narrow gauge, as recommended by the government. Blackman eventually won the contract, and as compensation Shea and Company was awarded the agency for the Newfoundland Railway Company, which began work in the summer of 1881. Improperly spent railway funds, so it was alleged, allowed Shea to create sufficient jobs in his district to win re-election in 1882. This contest saw the virtual coalition of the Conservative and Liberal parties against an amorphous New party, which opposed the railway, and with the appointment of Joseph Ignatius Little to the Supreme Court in 1883, Shea was without question the most senior and influential Catholic politician. The Liberal leadership, however, passed to Robert John Kent*. Having taken his nephew George Shea* into the business in 1884, Ambrose set his sights on imperial preferment. He collected a kcmg in 1883, the same year in which he acted as Newfoundland’s commissioner at the International Fisheries Exhibition in London, and in 1884 he sent a note to the Canadian prime minister, Sir John A. Macdonald*, suggesting that the latter might like to support his bid to be appointed governor of Newfoundland. After all, he wrote, for 30 years he had been “never in office but always doing the work of those who were.”

This letter was written against a background of great political complexity. An Orange–Catholic riot at Harbour Grace late in 1883 and the ensuing trials of a number of Catholics accused of murder had placed the Liberal–Conservative coalition under great strain [see Sir Robert Thorburn; W. V. Whiteway]. This tension in turn imperilled colonial approval of an Anglo-French fisheries convention that the imperial government was anxious to conclude. Shea exerted his diplomatic talents to keep the Whiteway coalition together, a task in which he succeeded until February 1885, when the passage of an offensively anti-Catholic resolution in the assembly caused all Catholic members, including him, to sit as an independent Liberal group. Leaving his present and former colleagues to struggle through to the end of the session, Shea himself went to Washington as a delegate of the St John’s Chamber of Commerce. His task was to discuss with American authorities the possible renewal of the fisheries clauses of the Treaty of Washington, which were due to expire that July.

The visit caused a flurry of controversy. Some in Canada feared that Newfoundland had received permission to negotiate an independent treaty, while in Newfoundland there were those who felt that Shea had made the colony appear as a supplicant, when in fact it was in a position to drive a harder bargain than the Treaty of Washington. Shea had discussions with Thomas F. Bayard, the secretary of state, and then went on to Ottawa, where he saw Macdonald and the governor general, Lord Lansdowne [Petty-Fitzmaurice*]. His shuttle diplomacy helped prevent a fisheries crisis between the United States and Canada by instituting a modus vivendi, and it effectively paved the way for the substantive discussions on trade and fisheries that started in 1887. This contribution made Shea “persona gratissima” with the Colonial Office, where Frederick Arthur Stanley told him that his services would be suitably recognized. Lansdowne found Shea “pleasant and presentable” and reported that he had undertaken to press for confederation if appointed governor. Since Governor Sir John Hawley Glover* was ill, it seemed that Shea might achieve his ambition.

In Newfoundland, Shea assumed the leadership of the Liberal party as the general election scheduled for 31 Oct. 1885 approached. Most Protestant politicians had coalesced in the newly created Reform party under the compromise leadership of Robert Thorburn, and the campaign was virulently sectarian in nature. However, Shea discreetly opened negotiations with senior Reform politicians, offering the Catholic vote to Reform candidates in districts with Protestant majorities and broaching the question of an amalgamation of parties in the future. He did not, it seems, raise the matter of the governorship. Shea delivered the Catholic vote in the agreed districts, thus helping to ensure a Reform victory. He himself ran successfully in the Catholic district of St John’s East.

The election safely over, Shea departed for London. Glover had died at the end of September, and Shea had immediately begun to lobby for the succession. But he was not the only Newfoundlander in competition: Carter, now chief justice, also wanted the post and was supported by Whiteway, who, having resigned from politics, was angling for a seat on the bench. In the event, the Colonial Office decided to appoint Shea, presumably because of his pro-Canadian attitudes and proven diplomatic abilities. It was an insensitive decision. Shea was the Catholic leader of the Catholic opposition party, and was certainly not acceptable to senior politicians in the colony. Once the news became known in St John’s late in December, the protests gathered strength. Thorburn, now premier, Carter, Whiteway, the chamber of commerce, all joined in the chorus. The government prepared to resign if the appointment went through. In the face of such opposition the Colonial Office had to withdraw Shea’s name. A bitterly disappointed Shea returned to St John’s late in February 1886 and treated his sympathetic constituents to a venomous public speech attacking his opponents and alleging that he was the victim of Orange bigotry.

His replacement as governor was Sir George William Des Vœux, who reported that Shea felt the slur keenly and had been placed in a “painful and humiliating position.” Though Shea huffed about his ability to bring the government down, and the government certainly feared his influence, he did not seriously attempt to embarrass the new administration when the assembly met. Des Vœux did what he could to promote a rapprochement and the government, unwilling to upset Shea further, appointed his brother Edward, who had incongruously stayed on as colonial secretary, cashier (general manager) of the Newfoundland Savings’ Bank and president of the Legislative Council. Further, it did not try to change the transatlantic steamship agency when the contract came up for renewal.

In the summer of 1886 the bitterness caused by the 1885 election had lessened sufficiently that the amalgamation of parties planned the previous year could take place – though in Shea’s absence. He had become an awkward and uncomfortable presence, and Des Vœux recommended that he be considered for the post of consul general at New York, passing on the Newfoundland government’s desire to see Shea employed elsewhere. In the event, the government sent him to London to negotiate the colony’s first foreign loan and to press its case for royal assent to an act to control the sale of bait [see Des Vœux; Thorburn]. He returned to Newfoundland briefly early in 1887 and then went back to London with Thorburn, the pair forming Newfoundland’s delegation to the first Colonial Conference. They successfully arranged for royal assent to the bait bill, and Shea completed negotiations for a second loan. The news that Des Vœux was leaving Newfoundland revived his hopes for the governorship, but neither Thorburn nor Des Vœux was prepared to support him. There must have been a universal sigh of relief when the Colonial Office decided that Shea could have the vacancy created in the Bahamas by the transfer to Newfoundland of Henry Arthur Blake.

Shea left for his new post in October 1887. He remained in the Bahamas until December 1894, by all accounts an energetic and popular figure, closely associated with the promotion of sisal plantations. Though he never returned to Newfoundland to live, retiring instead to London in 1895, he remained closely in touch with local affairs, and never lost his desire to reverse the slight he had suffered in 1885–86 and be appointed governor. In 1888 he attempted to involve himself in abortive confederation negotiations – Macdonald brushed him off – and as late as 1894 solicited Canadian support for the governorship. Whiteway, who returned to the premiership in 1889, thought Shea a malign influence, with some reason, given Shea’s suit against the government for commissions on the loans negotiated in 1886–87 and his advice to the Colonial Office in 1891 not to give the colony financial assistance since it would be misapplied. Whiteway’s suspicions became more acute when Joseph Chamberlain was appointed secretary of state for the colonies four years later, since Shea had induced Chamberlain to invest in Bahamian sisal and the two were well acquainted.

Ambrose Shea retained a lasting bitterness against those who had denied him the Newfoundland governorship, and perhaps also resentment against a community that had prevented him from rising to high office. Newfoundland society, small and in some respects intolerant, clearly restricted Shea, who needed a larger stage on which to display his ability and pursue his ambitions. Always an outsider in his own land, he had many friends but few supporters, many admirers but few followers. His death in 1905 was the occasion for St John’s, at least, to try to make amends. His remains were brought back from London, and there was a lying-in-state in the Legislative Council chamber and a state funeral. He was the first Newfoundlander to receive such elaborate obsequies, a sign of his fellow-countrymen’s pride in his achievements, but as well an expression of unease that one so talented had ended his life in self-imposed exile.

[Details concerning Shea’s family and his municipal activities, respectively, were kindly supplied by doctors John Mannion and Melvin Baker, both of St John’s. A letter of 15 June 1895 from Sir William Vallance Whiteway to Robert Bond*, concerning Whiteway’s suspicions about Shea, is found in the Bond papers, which remain in private custody. j.k.h.]

Arch. du Ministère des Affaires Étrangères (Paris), Corr. consulaire, corr. politique, Terre-Neuve, I: 87 (mfm. at NA). Centre for Newfoundland Studies, Memorial Univ. of Nfld (St John’s), Arch., COLL-26 (W. V. Whiteway papers), esp. Harvey to Whiteway, 1 Jan. 1886; Shea, copy of speech, February 1886. Maritime Hist. Arch., Memorial Univ. of Nfld, Keith Matthews coll., ser.i, esp. Shea name file. NA, MG 26, A, 196832–35, 203764–70, 204389; 528: 166, 171. PANL, GN 1/3/A, F. B. T. Carter, memorandum on the Newfoundland Railway, April 1886; GN 2/2, E. D. Shea to Thorburn, 8 Jan. 1886; MG 271, box 3, file 10. Private arch., E. J. Stanley, 18th Earl of Derby (Prescot, Eng.), Papers of E. H. Stanley, 15th Earl of Derby, Lansdowne to Derby, 9 June 1885 (mfm. at NA). PRO, CO 194/208–10, 194/220; CO 537/120. Courier (St John’s), 17 March 1860; 30 Jan., 2 Feb. 1861; 16 April 1873. Evening Mercury (St John’s), 28 April, 12 May 1885; 22 June 1887. Evening Telegram (St John’s), 3 July, 20 Sept. 1886; 26 Sept. 1887; 6 July 1891; 17 May 1893; 29 Sept. 1901; 4 Aug. 1905. Harbor Grace Standard (Harbour Grace, Nfld), 20 March 1875. Morning Chronicle (St John’s), 2 June 1866; 1, 22 June, 13 July, 3 Aug., 1, 8 Oct. 1869. Newfoundlander, 4 May, 11 June 1855; 3 March, 14 Nov. 1859; 9 March 1861; 17 Nov. 1864; 19 April 1866; 27 April 1868; 25 May, 22, 29 June 1869. Newfoundland Express (St John’s), 29 Jan. 1862. Patriot and Terra-Nova Herald (St John’s), 3 Oct. 1859, 6 Sept. 1869, 5 Oct. 1874. Public Ledger, 27 April 1860. Terra Nova Advocate and Political Observer (St John’s), 18 Dec. 1878, 18 Jan. 1879.

Paul Albury, The story of the Bahamas (London, 1975). Melvin Baker, “The government of St. John’s, Newfoundland, 1800–1921” (phd thesis, Univ. of Western Ont., London, 1981). R. C. Brown, Canada’s National Policy, 1883–1900: a study in Canadian-American relations (Princeton, N.J., 1964). Geoff Budden, “The role of the Newfoundland Natives’ Society in the political crisis of 1840–1842” (history honours thesis, Memorial Univ. of Nfld, 1983). Michael Craton, A history of the Bahamas (3rd ed., Waterloo, Ont., 1986). P. K. Devine, Ye olde St. John’s, 1750–1936 (St John’s, 1936). Frank Galgay, The life and times of Sir Ambrose Shea, father of confederation (St John’s, 1986). J. P. Greene, “The influence of religion in the politics of Newfoundland, 1850–1861” (ma thesis, Memorial Univ. of Nfld, 1970). G. E. Gunn, The political history of Newfoundland, 1832–1864 (Toronto, 1966). J. [K.] Hiller, “Confederation defeated: the Newfoundland election of 1869” and “The railway and local politics in Newfoundland, 1870–1901,” Nfld in 19th and 20th centuries (Hiller and Neary), 67–94 and 123–47; “Hist. of Nfld.” W. A. Kearns, “The Newfoundlander and Daniel O’Connell’s great repeal year: a response from ‘Britain’s oldest colony’” (paper presented at the annual meeting of the American Committee for Irish Studies, New England Conference, Chicopee, Mass., 1986). R. V. Kubicek, The administration of imperialism: Joseph Chamberlain at the Colonial Office (Durham, N.C., 1969). Elinor [Kyte] Senior, “The origin and political activities of the Orange order in Newfoundland, 1863–1890” (ma thesis, Memorial Univ. of Nfld, 1959). The life and letters of the Rt. Hon. Sir Charles Tupper . . . , ed. E. M. Saunders (2v., London, 1916). J. [A.] Macdonald, Correspondence of Sir John Macdonald . . . , ed. Joseph Pope (Toronto, 1921). W. D. MacWhirter, “A political history of Newfoundland, 1865–1874” (ma thesis, Memorial Univ. of Nfld, 1963). D. C. Masters, The Reciprocity Treaty of 1854 . . . (London, [1937]). E. C. Moulton, “The political history of Newfoundland, 1861–1869” (ma thesis, Memorial Univ. of Nfld, 1960). Nfld, House of Assembly, Journal, 1865, app.: 654. Paul O’Neill, The story of St John’s, Newfoundland (2v., Erin, Ont., 1975–76). E. A. Wells, “The struggle for responsible government in Newfoundland, 1846–1855” (ma thesis, Memorial Univ. of Nfld, 1966).

Cite This Article

J. K. Hiller, “SHEA, Sir AMBROSE,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 13, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed January 1, 2026, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/shea_ambrose_13E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/shea_ambrose_13E.html |

| Author of Article: | J. K. Hiller |

| Title of Article: | SHEA, Sir AMBROSE |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 13 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1994 |

| Year of revision: | 1994 |

| Access Date: | January 1, 2026 |