Source: Link

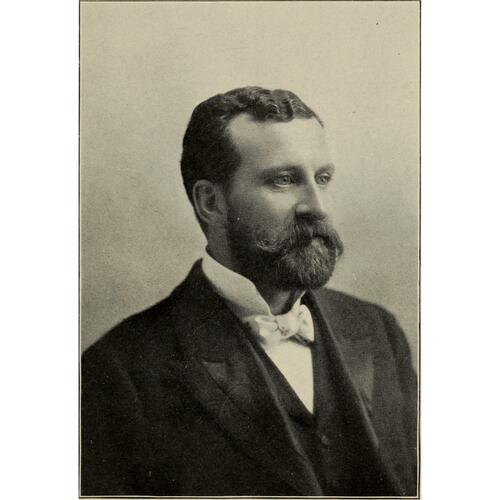

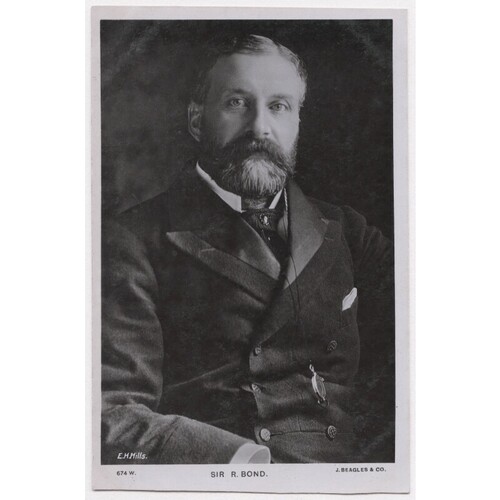

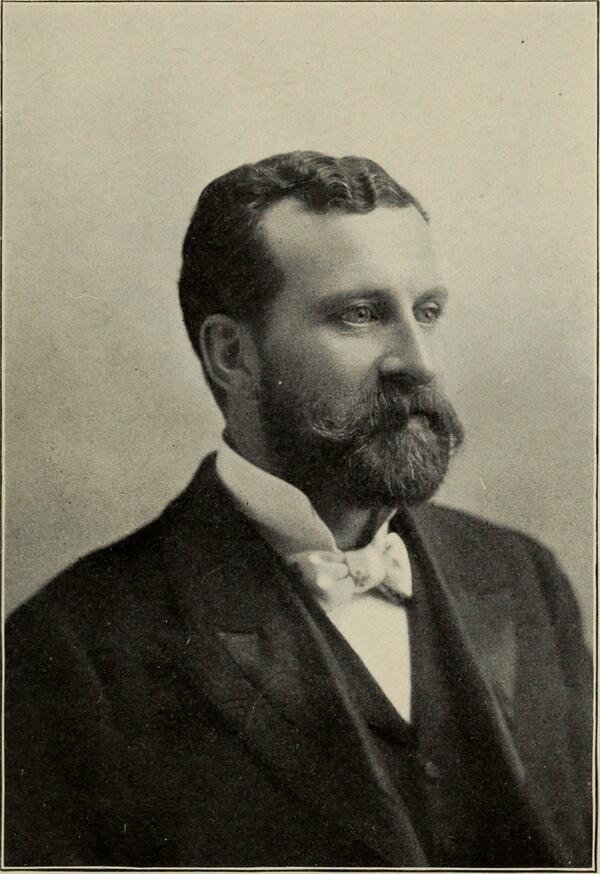

BOND, Sir ROBERT, politician and country gentleman; b. 25 Feb. 1857 in St John’s, son of John Bond of Kingskerswell, England, and Elizabeth Parsons; d. unmarried 16 March 1927 in Whitbourne, Nfld.

John Bond first worked in Newfoundland for Samuel Codner* of Kingskerswell, and eventually owned his own business in St John’s. He and Elizabeth Parsons married in 1847 and had seven children, of whom Robert Bond was the sixth. Robert spent five years at St Andrew’s School in St John’s and then a year at the General Protestant Academy. In April 1872 he was enrolled at the Taunton Wesleyan Collegiate Institution in Somerset, England. Two months later his father was seized with paralysis and died. In 1925 Robert would remember “the debacle of 1872–3.” Nevertheless, he persevered in his studies, and won a prize for solo singing. At some stage he learned to play the piano.

John Bond had willed that his real and personal property in Newfoundland should be liquidated following his death and the proceeds invested in interest-bearing securities. The interest was to be paid first to Elizabeth but bequests were made to surviving children as well. Robert and his brothers George John and Henry benefited from these, and George and Robert were also beneficiaries under the wills of Henry and of their cousin John Bussell Bond of Montreal, who helped manage the family affairs. When Elizabeth died in 1900, her life interest in the residue of her husband’s estate passed in equal shares to George and Robert.

On 10 April 1874 John Bond’s estate had been valued at $54,932.66. As of 14 June 1886 it held to the credit of Elizabeth and Robert (half each) 200 shares in the Canadian Bank of Commerce, 100 shares in the Banque du Peuple, and 19 shares in the Ontario Bank. From John B. Bond, Robert ultimately received 24 shares in the Bank of Montreal. In 1896 Elizabeth and Robert lost $7,062.50 through the failure of the Banque du Peuple [see Jacques Grenier*] and $2,974.68 through the sale of their shares in the Ontario Bank. Despite these reverses, Robert was a wealthy man through the whole of his adult life. Money allowed him to be that rara avis in Newfoundland public life – the politician who could pay his own way.

On 11 Dec. 1874 Robert and Elizabeth (as guarantor) entered into an agreement with the prominent St John’s lawyer William Vallance Whiteway* whereby Robert became a law clerk for a term of five years. Bond was not, however, called to the bar, apparently for medical reasons. After travelling to Europe in 1880 and spending some ten weeks camping on the west coast of Newfoundland the following year, he entered politics. Whiteway had become premier in 1878, and in 1881, as part of his policy of progress, construction was started on a railway from St John’s to Halls Bay. In the general election of 6 Nov. 1882, which Whiteway won handily, Bond was returned for the government in Trinity Bay. Whiteway’s Conservative party was Protestant in nature but had formed an alliance in the House of Assembly with Roman Catholic Liberals. The government’s main opponents at this time were St John’s merchants opposed to the railway scheme.

In 1884 the syndicate contracted to build the railway went bankrupt, and the next year, taking advantage of a Protestant-Catholic blow-up at Harbour Grace in 1883, the merchants were able to separate Whiteway from his Roman Catholic supporters. As a consequence of this realignment, Bond succeeded Robert John Kent*, a leading Liberal, as speaker of the house on 27 Feb. 1885, two days after he had turned 28. Whiteway was eased out of office in October and was replaced as premier by Robert Thorburn*, who made an outright sectarian appeal. A general election, which Thorburn won, followed on 31 October, and Bond was elected as an independent in Fortune Bay. Thorburn offered him the speakership of the new house but he declined because he “could not conscientiously unite with a sectarian government.”

In February 1888, at the urging of Bond and the Canadian-born Alfred Bishop Morine*, Whiteway agreed to head a new political party. Bond became its secretary, but Morine soon bolted when he was resisted in his scheming for confederation. The previous year Bond had introduced a bill, passed by the legislature, that provided for the secret ballot, and the election of 6 Nov. 1889 would be the first held under the new dispensation. Bond wrote the manifesto of the Whiteway (or Liberal) party. Dated 22 June 1889, it promised railway construction and resource development, but rejected confederation. Whiteway won the election and Bond was returned for Trinity. On 17 Dec. 1889 he was appointed colonial secretary in the new government.

Bond’s business interests had also developed apace in the 1880s. On 18 Feb. 1884 he and Alexander McLellan Mackay* bought a property of eight square miles in the interior of the Avalon peninsula. Near its centre was Harbour Grace Junction, which the railway from St John’s had reached the year before. In 1887 the property was transferred to the Townships Timber and Land Company, which had Bond and Mackay as principal shareholders. Bond was elected president of the company, which sought “to establish a Township, carry on a lumber business, and dispose of the lands by sale to bona fide settlers.” In 1887 a plan was devised for the proposed town, and in May 1889, on Bond’s initiative, the legislature passed a bill changing the name of Harbour Grace Junction to Whitbourne, in honour of Sir Richard Whitbourne*, an early English promoter of Newfoundland.

Bond set out to make Whitbourne, Newfoundland’s first inland town, a model community. The company ran a sawmill at Junction Lake, and Bond built a house near Whitbourne which he first used “as a hunting box” and then enlarged into a permanent home known as The Grange. In 1903, after the company had decided to wind up its business, he bought the entire Whitbourne property at public auction. By this time he had left his lovely Victorian neo-Gothic residence in St John’s and was living at The Grange (his mother had died there). Over the years he devoted considerable time, energy, and money to the beautification and development of his estate. His house stood on a hill, was situated near a lake, and had a commanding view. At The Grange, Bond was the master of all he surveyed.

He had also been involved from the late 1870s onwards in mining speculation. He had an interest in the Colchester mining property situated on the Southwest Arm of Green Bay, and on 15 Dec. 1892 he obtained a grant for another mining property, northwest of Georges Lake and inland south of Bay of Islands. Over the years he spent twenty thousand dollars developing this property, which had an asbestos deposit, but he never realized a return from his investment and was never able to sell the mine.

As colonial secretary, Bond was deeply involved in the continuing struggle over the French Shore, the ribbon of territory along the northern and western coasts of the island where French fishermen enjoyed fishing and landing rights. In July 1890 Bond and Liberal mha George Henry Emerson (speaker of the House of Assembly) visited the area. They then went to England, where they joined Whiteway and Augustus William Harvey* as an official delegation to press Newfoundland’s claim for full control of its territory. They did not get very far in their lobbying vis-à-vis the French, but Whiteway was able to persuade the British to allow Newfoundland to seek a reciprocity agreement with the United States.

The background to this initiative was tangled and involved American fishing rights under the Anglo-American Convention of 1818. A number of disputes had flared up over the meaning of the fisheries clauses, but these had been smoothed over by provisions first in the Reciprocity Treaty of 1854 and then in the Treaty of Washington in 1871. Until the United States served notice that it intended to abrogate the latter treaty on 1 July 1885, Newfoundland had not challenged the principle of British North American solidarity in negotiations with the Americans. But the American action and its diplomatic aftermath encouraged experimentation. By permitting Newfoundland to explore prospects in Washington, the British seemingly accommodated this.

Bond was chosen to represent Newfoundland in the proposed negotiations. On 7 Oct. 1890 he met with Secretary of State James Gillespie Blaine in Washington and he subsequently went to New York and to Boston and Gloucester, Mass., to explain Newfoundland’s position to various business groups. On 18 October the British envoy to the United States, Sir Julian Pauncefote, submitted a draft convention for Blaine’s consideration, whereupon Bond returned to Newfoundland. He was summoned back in November for further discussion. Having learned to his chagrin that Pauncefote was not authorized to sign the proposed convention, Bond seized the initiative and met privately with Blaine in mid December. These talks produced an agreement that Bond later claimed in the House of Assembly “could not but be acceptable” to his “bitterest opponent . . . in the island.” He returned home flushed with triumph, but disappointment followed when the imperial authorities decided to hold the Bond-Blaine Convention in abeyance, on the grounds that the talks in Washington had been unofficial and that Canada had not been properly consulted. In effect, Canada was allowed to veto a deal that Newfoundland valued highly.

Needless to say, this outcome soured relations between St John’s and Ottawa. In the spring of 1891 Newfoundland denied Canadian fishermen licences to purchase bait and a bitter round of mutual reprisals followed. On 25 June, while this sparring was in progress, Bond mused to Whiteway about Newfoundland’s long-term prospects given the realities of falling public revenue and continuing migration from the colony. His preferred option was reciprocity with the United States “apart from the Canadians.” If this could not be achieved, the colony should seek a financial guarantee from the imperial government “but not subject to us handing over the control of our affairs to them.” Otherwise, the only recourse was confederation. Present circumstances might be propitious for obtaining favourable conditions. The threat of reciprocity could be “used as a lever,” as could the disruption of the bait supply, which was already causing Canada “a considerable loss.” As Bond imagined events unfolding, the negotiation of terms of union by Whiteway would be followed by a plebiscite in Newfoundland.

Confederation would indeed become a live issue, but in circumstances quite unlike those imagined by Bond. In the interim, from 9 to 15 Nov. 1892, the two countries held a conference at Halifax to try to resolve their differences. Newfoundland was represented by Whiteway, Bond, and Harvey and Canada by Mackenzie Bowell*, Joseph-Adolphe Chapleau*, and Sir John Sparrow David Thompson*. Various proposals were examined, but in the end nothing concrete was achieved and Newfoundland continued to lobby the imperial government to complete the Bond-Blaine Convention.

On 29 July 1893, following several months of reflection, ill health, and growing disillusionment with Whiteway’s performance (especially in relation to French Shore matters, where he objected to the premier’s propensity to compromise), Bond submitted a letter of resignation from the government, but he did not in fact leave. In the election of 6 Nov. 1893 he was returned in Trinity and the government won a seemingly comfortable majority of 13 seats. But on 6 Jan. 1894, with Morine to the fore, the Tories petitioned the Supreme Court under the Controverted Election Act of 1887 alleging wrongdoing by Whiteway, Bond, and 15 other Liberals. In the first case to be heard, the judge, Sir James Spearman Winter*, found that public funds had been spent without proper authority and the two members involved were unseated and disqualified. Faced with the prospect of losing his majority by judicial attrition, Whiteway told Governor Sir John Terence Nicholls O’Brien* that he intended to act on behalf of those adversely affected by the litigation. When the governor proved uncooperative, Whiteway resigned, and on 14 April Augustus Frederick Goodridge formed a minority Tory government. Court proceedings continued and on 25 July 1894 Whiteway and Bond were themselves unseated and disqualified.

This upheaval was followed in December 1894 by the failure of the colony’s two main banks, the Commercial Bank of Newfoundland and the Union Bank of Newfoundland, as foreign investors and financiers lost confidence in the local economy and maladministration caught up with the banks’ directors [see James Goodfellow*]. Since the Newfoundland Savings Bank, the only other financial institution in St John’s, had its assets tied up in unsaleable colonial debentures and notes of the failed banks, its position was also threatened.

With the government itself facing bankruptcy, Goodridge sought financial assistance from the imperial government. When this was not forthcoming, he resigned, and on 13 Dec. 1894 a Liberal administration led by Daniel Joseph Greene was formed. Greene immediately had legislation passed removing the disqualifications from the unseated members, and then he too resigned. These moves cleared the way for Whiteway to become premier again on 8 Feb. 1895. Bond was reappointed colonial secretary the same day and from 25 April 1895 he sat in the Legislative Council. He would return to the House of Assembly when he was acclaimed in Twillingate in a by-election scheduled for 26 Sept. 1895. He was to represent this district for the remainder of his political career.

Back in office, Whiteway and Bond faced a bleak situation but they nonetheless refused to accept an imperial demand for an inquiry by royal commission in return for assistance. Instead, they approached Canada to ascertain what terms would be available for confederation. Since Whiteway was in poor health, Bond led the delegation to Ottawa in March 1895. Negotiations commenced on 4 April but the Canadians offered less than the Newfoundlanders were prepared to accept, and the British were unwilling to bridge the difference.

Bond had better luck with the bankers. With the help of the railway promoter Sir Robert Gillespie Reid*, who had burst on the Newfoundland scene in 1890, he was able – through intelligent and tough-minded negotiation – to rescue the colony’s finances with timely loans in Montreal and London. As part of a complex deal, Bond backed a short-term loan for the savings bank with a personal guarantee of $100,000. On 23 July 1895 he arrived back in St John’s a conquering hero. Thereafter he had a golden reputation as the man who had been willing to risk his fortune to save his country. In fact, the personal guarantee he made cost Bond and his mother the reverse they suffered in the failure of the Banque du Peuple. Because of it, his broker “was not in a position to sell out” and the result was a “total loss.”

Despite Bond’s success, the Liberals lost the election of 28 Oct. 1897 to a revived Tory party led by Winter, who had abandoned his judgeship. Whiteway was personally defeated and left it to his caucus to decide who should lead them in the assembly. Bond was duly selected, but Whiteway, who nominally remained leader of the party, eventually became embittered and turned against him.

On 3 March 1898 the Winter government entered into a contract with Sir Robert G. Reid for the operation of the trans-island railway, which Reid had finished building to Port aux Basques (Channel–Port aux Basques) under agreements, involving financial payments and land grants, made in 1890 and 1893. Winter’s 1898 contract, the details of which had been known since 22 February, gave Reid the right to operate the railway for a 50-year period and additional land grants in return for an immediate payment of $1 million. At the end of this period Reid’s heirs would own the railway. Reid also undertook to establish a coastal steamer service, take over the government telegraph lines, purchase the dry dock in St John’s, and provide the capital with electricity and a streetcar service. Bond condemned the contract, which required legislative approval, on the grounds that it would transfer public assets for much less than their worth and establish a monopoly. By contrast, Edward Patrick Morris*, the Liberal member for St John’s West, endorsed the deal because it would relieve the financial crisis and provide badly needed employment, particularly in the capital. At a caucus meeting on 23 February he had broken with Bond on the issue. When Bond lost the fight in the assembly, he called upon the Colonial Office to disallow the legislation embodying the Reid contract, but the imperial authorities refused to interfere.

In November 1898, while the battle over the contract was still raging, it became known that Alfred Morine, a member of the cabinet, had acted as Reid’s solicitor during the drafting of the railway bill and was still representing him. Morine was forced to resign by Governor Sir Herbert Harley Murray* and this move split the government party. Four leaders – Winter, Morine, Bond, and Morris – now bargained for support, but Bond was able to turn this situation to his advantage. At a public meeting in St John’s on 20 Oct. 1899 he was unanimously chosen as leader of the Liberal party after a letter of resignation had been read out from Whiteway. Having thus far played a secondary and supportive role to Whiteway, Bond had finally found a cause – the railway contract – that allowed him to outflank his old mentor.

On 19 Feb. 1900, with Morine in England, the Winter government lost a no-confidence vote in which several of Morine’s supporters broke ranks to join Morris, who in turn linked up with Bond. This defeat led to the resignation of the government and to the swearing in of Bond as premier on 15 March (he would also serve as colonial secretary). Having reached the top of the greasy pole of Newfoundland politics, Bond sought an immediate dissolution, but this was refused by Governor Sir Henry Edward McCallum, who favoured a fall election. Morris entered the Bond cabinet with a promise from the new premier, reluctantly given, that the Reid contract would be modified rather than cancelled. When the government, which had a majority of only two, entered into negotiations with Reid’s son William Duff over revising the contract, no agreement could be reached. But politically this outcome was an asset rather than a liability, for in the general election of 8 Nov. 1900 Bond won an overwhelming victory, taking 32 of 36 seats against a Morine-led opposition financed by the Reids.

His first priority after the election was to renegotiate the railway contract. This effort succeeded, and on 2 Aug. 1901 a new act became law whereby Reid gave up his reversionary interest in the railway, as well as control of the public telegraph system, and the government returned his $1 million with interest. For a payment of $850,000 Reid handed back 1.5 million acres in land grants and was permitted to form the Reid Newfoundland Company, which managed his landholdings and operated the railway, the coastal steamers, the St John’s street railway and electrical services, and the dry dock. With this legislation, an uneasy peace between Bond and the Reids was achieved.

During his premiership both Bond and Newfoundland attracted recognition in a number of ways. On 24 Oct. 1901 Bond was invested a knight during the visit to St John’s of the Duke and Duchess of Cornwall, and in 1902 he was sworn to the imperial Privy Council. He was also given the freedom of the city of Edinburgh in 1902 and of the City of London, Manchester, and Bristol in 1907. On 26 July 1902 he was awarded an honorary lld by the University of Edinburgh. In 1901 international attention had been drawn favourably to Newfoundland when, on 12 December, Guglielmo Marconi, who was welcomed to the colony and assisted by Bond, received the world’s first wireless message on Signal Hill, St John’s. Bond’s keen interest in this project was in keeping with his longstanding advocacy of a rapid transatlantic ship and train transportation route via Newfoundland.

Bond represented Newfoundland at the 1902 and 1907 colonial conferences in London and was photographed on both occasions with the other leaders of the British empire. At the 1902 conference he urged the enlargement of the force for which recruitment had started in Newfoundland in 1900 under the United Kingdom’s Royal Naval Reserve Volunteer Act of 1896. In the 1914–18 war the first Newfoundlanders to go overseas would be members of this reserve. In a further gesture of imperial solidarity, he introduced a bill, which received unanimous consent in the House of Assembly on 24 April 1903, to establish Empire Day [see Clementina Trenholme*] as a public holiday in the colony.

Economically, Bond benefited from large catches and good prices in the fishing industry and the revenue available from new timber and mining operations, especially the iron-ore mines on Bell Island, which had opened in 1895 under Canadian auspices to meet the needs of the blast furnaces at Sydney, N.S. Rising revenues enabled the government to be fiscally prudent while increasing expenditure on education, marine works, agriculture, and the colony’s communication system. In small communities it encouraged the unification of denominational schools into “amalgamated” ones, and in 1904 it began a coastal steamship service with Bowring Brothers to supplement that offered by the Reids. In labour relations, the Bond government weathered strikes of miners on Bell Island in 1900, of sealers in St John’s in 1902 [see Simeon Kelloway*], of longshoremen in St John’s in 1903, and of railway workers (against Reid Newfoundland) at Placentia in 1904.

As premier, Bond renewed his quest for reciprocity with the United States. Canada still strongly opposed a separate Newfoundland–United States deal but Ottawa’s arguments could no longer be sustained in London. Years had passed since the Bond-Blaine Convention had been negotiated, and Newfoundland could now scarcely be held accountable for undermining Canada’s bargaining position. In August 1902, with British approval, Bond went to Washington and began talks with Secretary of State John Milton Hay. Their agreement, signed in November, provided, inter alia, for duty-free entry into the United States for a sizeable list of Newfoundland exports and for privileged treatment of American fishing vessels in relation to a wide range of activities in Newfoundland. The proposed arrangement was a tribute to Bond’s persistence and skill but Massachusetts senator Henry Cabot Lodge, champion of the New England fishing industry and a key member of the Senate foreign relations committee, scuttled it. The agreement was not reported out of the committee until January 1905 and then only in an amended form that Newfoundland could not accept. Bond had lost another round in an old battle, and in the process had acquired a formidable new adversary.

Unquestionably, his greatest triumph as premier was in relation to French rights in Newfoundland. He had failed to get the French Shore question on the agenda of the 1902 Colonial Conference, but in 1904 he became the unintended beneficiary of France’s decision to seek a rapprochement with Great Britain. Suddenly, the way was clear for London to trade off concessions elsewhere in the world for a satisfactory resolution of the French Shore issue. Under the terms of the deal eventually embodied in the Entente Cordiale of 8 April 1904, France renounced her rights in Newfoundland under the Treaty of Utrecht (1713), but retained summer fishing, though not landing, rights along the former Treaty Shore. A note accompanying the agreement guaranteed that Newfoundland would not be allowed to cut off bait supplies to French fishermen working legitimately on the coast by denying them purchasing licences.

Bond approached the agreement cautiously but soon embraced it enthusiastically and fought back a motion of censure against the imperial government brought in the legislature on 27 April 1904 by the diehard Morine. At a stroke, a burden that Newfoundland had carried for almost 200 years had been lifted. Although Bond was fortunate to be in charge at the time, he was given full credit for the outcome. He was in consequence a national hero twice over. “The heritage is won at last,” the St John’s Evening Telegram trumpeted, “and to our children we can transmit unsullied and unstained by alien rights the rough and rugged shore of old Newfoundland.” The settlement highlighted Newfoundland’s general progress in this period and its status as an emerging North Atlantic dominion of the British empire.

It also set the stage for the general election held on 31 Oct. 1904. In this contest Bond’s Liberals faced a United Opposition party that had five leaders – Donald Morison, Winter, Goodridge, Morine, and the now disaffected Whiteway – and no real policy other than to oust the government. Bond characterized the opposition as Reid-backed confederates and ran on the government’s “record of public service.” He won 30 of 36 seats, and of his five main opponents only Morine was elected.

On 12 Jan. 1905 the government added to its laurels by signing an agreement with the Anglo-Newfoundland Development Company Limited that led to the opening of a pulp and paper mill at Grand Falls. The same year, however, Bond again crossed the Reids by refusing to buy their railway and steamship operations. Not surprisingly, this episode increased their determination to drive him from office. They did not have to wait long to get their chance, for in 1905 Bond also embarked on a crusade that ruined his political career. What he now attempted was to pressure his New England opponents into accepting the Bond-Hay agreement by disrupting their fishing operations in Newfoundland.

The Foreign Fishing Vessels Act of 1893 was amended so as to cut the Americans off from engaging local crews, buying fish, or obtaining necessary supplies. When the Americans countered by carrying on these activities outside the three-mile limit, Bond sought to close the loophole by a further amendment to the act, but this was vehemently opposed by Washington and blocked by London. The British saw no reason to jeopardize their developing friendship with the United States, a high policy objective, over the upstart behaviour of a minor colony. Bond had badly overstepped himself and soon paid the price for his miscalculation.

For the 1906–7 fishing season Bond’s machinations were circumvented by an Anglo-American modus vivendi that was imposed on Newfoundland. Another such agreement followed for 1907–8. In the meantime, the British had concluded that the only way out of a tricky situation in Newfoundland was to refer all outstanding issues under the Convention of 1818 to the Permanent Court of Arbitration at The Hague. Bond at first stubbornly refused this fig leaf, but while attending the Colonial Conference of 1907 gave way on the issue. His capitulation left the British to secure Canadian agreement for the proposed arbitration, something that Prime Minister Sir Wilfrid Laurier*, still smarting from the Alaska boundary decision of 1903, only reluctantly gave.

Bond’s last act in a long fisheries struggle was to agree, after more Sturm und Drang, to the terms of the reference to the Hague court, but this accommodation could not save him politically. As a result of his systematic defiance over many years of Ottawa, Washington, and London, he had accumulated many enemies abroad. Moreover, Newfoundlanders themselves were far from united in the struggle he had unleashed. On the west coast, the centre of the American fishery, Bond faced strong opposition from fishermen who enjoyed a profitable trading relationship with the New Englanders, and their cause found a sympathetic ear in Governor Sir William MacGregor, who sought to counter his first minister at every turn. Lord Grey*, the Canadian governor general, hoped that Bond’s discomfiture would provide an opening to bring Newfoundland into Canada. He and others, such as businessman Harry Judson Crowe, plotted to this end but ultimately nothing came of their efforts.

A more ominous development for Bond was the resignation from his cabinet on 26 July 1907 of Edward Morris, who had a fine political touch. Ostensibly, Morris broke with Bond over the wages being paid to road labourers in his constituency, but his departure was obviously timed to take advantage of Bond’s increasing adversity. In March 1908 Morris launched the People’s party, which brought together various interest groups and had close ties to the Reid Newfoundland Company. When an election was held on 2 Nov. 1908, the Bond and Morris parties each elected 18 members.

The deadlock produced a prolonged constitutional crisis. On 18 Feb. 1909 Bond advised the governor to dissolve the new house on the 25th, the day it was scheduled to open. When MacGregor refused, Bond submitted his resignation, which took effect on 3 March. Morris then became premier and a dissolution followed on 10 April. In the election held on 8 May, the People’s party won 26 seats and the Liberals 10. Bond’s loss was the more galling because of an incident that had occurred at Western Bay during the campaign. While landing there from a small boat on 30 April, he had been kicked back into the sea. Alfred W. Bishop, a fisherman, had been convicted in connection with this assault, but Bond’s accusations against John Chalker Crosbie*, the local People’s party candidate, who had been present on the wharf at the time, were to no avail. In 1905 Bond had gambled his political future on his ability to deliver for Newfoundland internationally, but he had misread diplomatic realities and underestimated the domestic political consequences of a punishing external fight. For his miscalculation, he paid a price that would haunt him for the rest of his life.

After the election Bond was a reluctant leader facing an entirely new situation in Newfoundland politics brought on by the formation of the Fishermen’s Protective Union (FPU). This organization, which flourished in the old Liberal territory of the northeast coast, had been established in 1908 by William Ford Coaker*, a former canvasser for the Liberals whom Bond had rewarded in 1902 with a minor appointment but who had annoyed the government by his union activities. Tired and dejected after fighting two bruising elections in just over six months, Bond was slow to recognize the potential of the FPU and of the challenge it posed for the Liberal party.

The FPU tapped into a deep and profound disillusionment among fishermen with Newfoundland’s economic system and grew rapidly in the northern bays. In 1910 it decided upon political action, with the object of holding the balance of power after the next election and thereby advancing its agenda of cooperation and fairness to the country’s small producers. Coaker’s emergence at the head of the FPU eventually forced Bond, a proud man, to deal as an equal with a former recipient of his patronage.

Coaker initially wanted an alliance with Bond, and on 16 Nov. 1911 he wrote to the Liberal leader in this regard. Bond replied that he believed in “union as a principle” and had advised Liberal supporters to join the FPU. Unions, he wrote, had often been of “real value by promoting intelligent communication between workpeople separated by wide areas and in ascertaining the due recompense of labour.” But Bond rejected the idea of a union party, telling Coaker that if he had known the FPU intended to run its own candidates, he would not have endorsed membership in the organization. The FPU should support “whatever political party” came “nearest to its ideals,” realizing that if it fought both parties, it could “hardly expect after the contest to exercise influence upon either.” “It has to be remembered that the two existing political parties, be they good or bad, stand for the whole people of the Colony, and that they ought to take into consideration the interests of the whole people.”

Coaker rejected this advice, and at the annual convention of the FPU on 27–30 Nov. 1911 won approval for the drafting of a political platform. To Bond’s chagrin, several senior Liberals were present as guests. An effort by William Frederick Lloyd*, editor of the Evening Telegram, a Liberal paper, to broker a deal between Bond and Coaker failed to overcome the deep division between them. As a result, when the FPU met in convention at Bonavista on 12–16 Dec. 1912 it proceeded to adopt its own election platform, which promised sweeping changes in the way Newfoundland was organized economically and socially.

With retirement very much on his mind and with his health failing, Bond went to England in February 1913 for medical examination. He thereby missed the pre-election session of the House of Assembly, leaving his members, who feared the consequences of a separate FPU campaign, demoralized and disorganized. On his return in April, Lloyd, James Mary Kent, and other senior Liberals pressed him to open negotiations with Coaker for an electoral pact. On 15 August, Bond invited the FPU leader to The Grange “to go fully into the matter undisturbed.” They met on 18 August, and on the 26th Bond followed up with a letter proposing a joint electoral effort whereby six nominations, one-sixth of the total needed for a full slate, would be reserved for the FPU. This offer, Bond maintained, was “very liberal recognition, for it must be remembered that the great majority of the fishermen are not Union men, and their views and interests may be at variance. If the Union has a claim to special representation, so has every trade, profession and business.” In return, Coaker pledged support for Bond’s leadership and for a “United Opposition,” but the alliance was less than solid. In his manifesto, published on 3 October, Bond played down his connection to the Bonavista Platform. On the other hand, Coaker nominated nine candidates instead of six, including seven in the eleven northern districts.

When the election of 30 Oct. 1913 was held, it was Morris who prevailed; the People’s party won 21 seats, the Union party 8, and the Liberals 7. With the exception of Port de Grave, where George Frederick Arthur Grimes was successful, all the Union party seats were in the north; the FPU had enjoined the voters to “sink or swim with Coaker.” The election put Bond in a most invidious position, “almost beyond the conditions of dignity and self-respect,” he complained. The Unionist members owed their first loyalty to Coaker, who had worked with the Liberals only as a “mere matter of expediency.” Coaker’s purpose would now be to lead the Union party to power in its own right. On 2 Jan. 1914 Bond resigned both the leadership of the Liberal party and his seat. James M. Kent then became leader of the party and, with Coaker’s approbation, leader of the opposition. Bond’s humiliation was made complete when Coaker was elected by acclamation in the by-election called to fill the vacant Twillingate seat.

From the quiet of The Grange, Bond followed political developments in Newfoundland through the Great War with a mixture of anger and disgust. Various appeals were made to him to re-enter public life, but he never sallied forth again. “I have had a surfeit of Newfoundland politics lately,” he acidly observed in November 1918, “and I turn from the dirty business with contempt and loathing.”

Bond’s denouement in the 1920s mixed a measure of contentment with considerable anguish. He never married but had living with him at the big house his cousin, the widowed Sarah Roberts, more than 19 years older than himself, and his housekeeper Mary Ford, “the good and faithful Mary.” Visitors were few. “I am not,” he would later write, “what the Americans designate ‘a good mixer.’ I am a very conservative Englishman.” His great delight was the daily round of The Grange and its farming operation. Bond enjoyed working with his hands and liked being out and about in his “Irish tweed jacket and riding breeches.” Nevertheless, on 28 Aug. 1922 he listed the Whitbourne estate for sale (though not for press advertisement) with Dowden and Edwards of St John’s. Nothing came of this initiative and in August 1924 he tried, again unsuccessfully, to sell the property to the government. In the end, he never moved. Instead he continued to indulge his love of country pursuits, which he believed had enabled him “to escape a tragedy and to convert my retirement from active politics into a pleasure.” He lived graciously, read widely, enjoyed bird-watching, loved music, and was an early radio enthusiast. Although he claimed to hate letter writing, he kept up a lively correspondence with his brother George and the latter’s son and daughter, Frank Fraser and Roberta.

Bond disliked St John’s and in the 1920s only infrequently visited the capital. Undoubtedly, his attitude was mixed up in his last years with his profound despair over “the deplorable condition of our public affairs.” With his ouster in 1909, he believed, Newfoundland had forsaken the “high-road of financial honesty” and was headed for a cataclysm that could only be avoided by “a radical change” in administration. His disillusionment extended even to the value of his own knighthood, which he described in 1920 as a “worthless appendage” given that “creatures of all kinds are dubbed knights and lords.” No doubt this vitriol was directed against his old nemesis Edward Morris, who in 1918 had received a barony. When Sir Richard Anderson Squires*, who had become premier in 1919 with Coaker’s support, called a general election for 3 May 1923, Bond forecast the worst: “My poor country! ‘The last phase.’” Squires was re-elected, but his government soon became embroiled in financial scandal and fell from power. Bond felt vindicated. “The community is rotten to the core. One is ashamed of this condition of things, heartily ashamed and sorry. But I will admit some satisfaction in looking down from this height, – it is the highest land in Avalon, – and saying to the dupes, – ‘I told you so.’” Even at this late date, he probably still imagined himself the political saviour of Newfoundland, but he was always content to indulge his hurt rather than seize an opportunity. When a public movement was started in 1926 to have him named governor, Bond growled that he “would much prefer to snare rabbits for a livelihood than to entertain the aristocracy that now finds its way into Government House.” In his despair over his country’s politics in the 1920s he helped foster the climate of opinion that in 1934 made possible the suspension of self-government in Newfoundland in favour of a commission of government [see Frederick Charles Alderdice*].

As the 1920s wore on, Bond was gradually overtaken by the problems of sickness and old age. He had a history of worrying about his health, and in 1921 had experienced an “explosion” that had left him “shattered in mind and body.” Cousin Sarah’s death from cancer in April 1924 left him broken and disconsolate. “I have passed through an experience,” he told Fraser, “that I hope you will never have, and I have passed through it alone. Alone! I now know all that word means, the misery, the despair, the horror it connotes.” As his physical condition deteriorated, he looked to family members, principally his niece, for emotional support. He was proud of Roberta’s academic achievements and her dedication to the sick (she would graduate in medicine from Dalhousie University in 1925), but he was not above bringing to her attention – teasingly perhaps but revealingly all the same – that the medical profession was “too indelicate for the female sex to dabble in.” He very much wanted Roberta to be the third woman in his life, after his mother and Sarah. Sadly for him, her understandable aspirations for a life of her own did not always mesh with his unquenchable personal needs.

In April 1924, having detected that something was bothering the 21-year-old Roberta, Bond invited her confidence: “Come out with it and I will see if I can prescribe a cure for your disease. I hope it is not a love affair for in that disease I unfortunately have no experience.” When, however, she told him that she was contemplating marriage to Edward Wilber Nichols, a classicist at Dalhousie who was 20 years her senior, he did not hesitate to interfere in the bluntest terms. Indeed, he attempted, unsuccessfully, to “veto” the marriage, telling her, in effect, that Nichols was not good enough for her. He also blamed her for an injury he had suffered soon after she visited The Grange in 1924. “It might have been all avoided,” he scolded, “if you had not so precipitately left me to the fates.” Roberta’s relationship with her devoted but irascible and possessive uncle survived his harsh words, though it must have been sorely tested. After obtaining her degree, she went to stay with him and to practise in the Whitbourne area. Her presence buoyed him up but his physical decline continued inexorably. When she left Newfoundland in June 1926, he followed her with a blameful letter.

Christmas that year was “a quiet one.” Although Bond enjoyed the rituals of the season, and liked to decorate his house “with evergreens and ferns and flowers,” he sat alone at the table for Christmas dinner. No doubt Mary Ford came in afterwards for “her annual glass of old port wine,” but there was no mistaking the melancholy of the occasion, the more so because Bond was convinced that “the dear ones” who had once dined with him “were not far away.” On 1 Feb. 1927, alarmed by the irregularity of his heartbeat, Bond went to St John’s to see his physician, James Sinclair Tait, who was surprised at the change for worse in his condition. He could hardly make it back to Whitbourne. On 28 February, three days after his 70th birthday, he told his brother that he was “failing rapidly.” George Bond arrived in St John’s on 10 March and the same day he and Dr Tait travelled to Whitbourne, where they found Robert at death’s door. Though now himself 76, George set about giving his brother “poor rough, ignorant nursing.” The end came “very quietly” at about 8:30 p.m. on 16 March.

George took charge of laying out the corpse and waked the remains in the house until 21 March, in deference to Robert’s request that he not be buried until George was “sure that he was dead.” Robert had made it known that he “wanted no fuss or parade.” Accordingly, the ceremony on 21 March was a simple one. The remains were carried to St John the Baptist Anglican Church in the estate’s express wagon, which George had painted black for the occasion. To accommodate the many friends and public figures who came out from St John’s, the Newfoundland Railway laid on a special train (at, George noted, its usual tariff). When all was done, Bond was buried in the rocky soil of the Avalon peninsula, a region he had explored as a youth and celebrated as a man. A sheaf of carnations sent by Roberta had been placed “across his heart inside the casket.”

Bond left behind him a tangled will, made on 28 Dec. 1914, in which he named George as executor. The inventory attached to the petition for probate valued the estate at $92,750 (in a 1924 accounting Bond had estimated his worth at $141,251.86). He left his Whitbourne holding, described as “an ideal property,” to the governor and Executive Council “to be held in trust by them for the people of Newfoundland as a Model Farm forever.” Most of the rest of his estate passed to Fraser but there were specific bequests to George, Roberta, Sarah (had she been living), and Mary Ford. After due consideration, the government declined the gift of the property on the grounds that the proposed model farm would be costly, of limited educational benefit, impractical to operate “free from political control,” and an unfair source of competition for private farmers. It accepted various bequests to the museum in St John’s, however, and these were presented to the governor at a ceremony held in Government House on 7 Oct. 1927.

Since the will was silent on what should be done if the government declined the Whitbourne property, George Bond sought the direction of the Supreme Court. The decision in 1928 awarded the property to Fraser, who coveted it. In 1949 Fraser sold the residence and four square miles of the estate to the new province of Newfoundland, which planned to establish a reform school there. Three years later authority was given for The Grange, the house of Bond’s dreams and the monument to all he held dear, to be removed. In this act of blind cultural vandalism the people of Newfoundland and Labrador lost one of their most unusual and important legacies.

In his public life Bond had been a Newfoundland nationalist, an ardent imperialist, and an advocate of reciprocity with the United States. This impossible combination produced much torment and disappointment. In his private life, especially in his project of The Grange, he sought to create a world within a world, but this goal too proved elusive. Though his vocation was politics, it was the visionary project at Whitbourne that defined the man. Bond was a complex historical figure whose career was emblematic both of Newfoundland’s ambitions and of its limitations. He is remembered variously, most intimately in a memorial window, depicting William Holman Hunt’s The Light of the World, at St John the Baptist, Whitbourne. This window was donated by Fraser Bond and Roberta Nichols and was dedicated on 7 Sept. 1927.

Centre for Newfoundland Studies, Memorial Univ. of Nfld, Arch. (St John’s), coll-236 (George J. Bond papers); coll-237 (Robert Bond papers). Memorial Univ. of Nfld, Dept. of Geography, Gordon Handcock coll. PANL, GN 2/39/A, 1921, Whitbourne. Private arch., Randall Nelson (Ottawa), Bond family research collection; J. R. Nichols (Digby, N.S.), Bond family research collection. Queen’s College, Taunton (Somerset, Eng.), [formerly Taunton Wesleyan Collegiate Institution], Admissions reg. Univ. of Edinburgh Library, Special Coll. Dept. Daily News (St John’s), 1909. Evening Herald (St John’s), 1898. Evening Mercury (St John’s), 1889. Evening Telegram (St John’s), 1889–90, 1894–95, 1898–1901, 1904, 1909, 1914, 1923, 1927, 1949. Royal Gazette and Newfoundland Advertiser (St John’s), 1889, 1894–95, 1900, 1909. Times (London), 1907. Melvin Baker, “The government of St John’s, Newfoundland, 1800–1921” (phd thesis, Univ. of Western Ont., London, 1980). Melvin Baker and P. [F.] Neary, “Sir Robert Bond (1857–1927): a biographical sketch,” Newfoundland Studies (St John’s), 15 (1999): 1–54. A. K. Bond, The story of the Bonds of earth (Baltimore, Md, 1930). Burke’s genealogical and heraldic history of the peerage, baronetage and knightage, ed. Peter Townend (104th ed., London, 1967). B. C. Busch, “The Newfoundland sealers’ strike of 1902,” Labour (St John’s), 14 (1984): 73–101; The war against the seals: a history of the North American seal fishery (Kingston, Ont., and Montreal, 1985). St John Chadwick, Newfoundland: island into province (Cambridge, Eng., 1967). Jessie Chisholm, “Organizing on the waterfront: the St John’s Longshoremen’s Protective Union (LSPU), 1890–1914,” Labour, 26 (1990): 37–59. Coaker of Newfoundland by J. R. Smallwood, ed. Melvin Baker (Port Union, Nfld, 1998). D. J. Davis, “The Bond-Blaine negotiations: 1890–1891” (ma thesis, Memorial Univ. of Nfld, 1970). Decisions of the Supreme Court of Newfoundland, 1927–31, ed. E. P. Morris et al. (St John’s, 1948), 12. Directory, St John’s, Harbour Grace, and Carbonear, 1885/86. DNLB (Cuff et al.). W. J. S. Donnelly, A general statement of the public debt of the colony of Newfoundland from its commencement in 1834 down to 31st December 1900, and a yearly analysis of the same (St John’s, 1901). Encyclopedia of Nfld (Smallwood et al.), 4. F. W. Graham, “We love thee, Newfoundland”: biography of Sir Cavendish Boyle, k.c.m.g., governor of Newfoundland, 1901–1904 (St John’s, 1979). J. [K.] Hiller, “A history of Newfoundland, 1874–1901” (phd thesis, Univ. of Cambridge, 1971); “The Newfoundland fisheries issue in Anglo-French treaties, 1713–1904,” Journal of Imperial and Commmonwealth Hist. (London), 24 (1996): 1–23; The Newfoundland Railway, 1881–1949 (St John’s, 1981); “The origins of the pulp and paper industry in Newfoundland,” Acadiensis (Fredericton), 11 (1981–82), no.2: 42–68; “The political career of Robert Bond,” in Twentieth-century Newfoundland: explorations, ed. J. [K.] Hiller and P. [F.] Neary (St John’s, 1994), 11–45. R. B. Joyce, Sir William MacGregor (Melbourne, Australia, 1971). Margaret McBurney and Mary Byers, True Newfoundlanders: early homes and families of Newfoundland and Labrador (Toronto, 1997). I. D. H. McDonald, “To each his own”: William Coaker and the Fishermen’s Protective Union in Newfoundland politics, 1908–1925, ed. J. K. Hiller (St John’s, 1987). Harvey Mitchell, “Canada’s negotiations with Newfoundland, 1887–1895,” CHR, 40 (1959): 277–93; “The constitutional crisis of 1889 in Newfoundland,” Canadian Journal of Economics and Political Science (Toronto), 24 (1958): 323–31. P. [F.] Neary, “The embassy of James Bryce in the United States, 1907–13” (phd thesis, Univ. of London, 1965); “Grey, Bryce, and the settlement of Canadian-American differences, 1905–1911,” CHR, 49 (1968): 357–80; Newfoundland in the North Atlantic world, 1929–1949 (Montreal and Kingston, 1988). P. [F.] Neary and S. J. R. Noel, “Newfoundland’s quest for reciprocity, 1890–1910,” in Regionalism in the Canadian community, 1867–1967, ed. Mason Wade (Toronto, 1969), 210–26. Newfoundland: economic, diplomatic, and strategic studies, ed. R. A. MacKay (Toronto, 1946). Newfoundland in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries: essays in interpretation, ed. J. [K.] Hiller and P. [F.] Neary (Toronto, 1980). Nfld, General Assembly, Proc., 1911, 1927; House of Assembly, Journal, 1885, 1887. S. J. R. Noel, “Politics and the crown: the case of the 1908 tie election in Newfoundland,” Canadian Journal of Economics and Political Science, 33 (1967): 285–91; Politics in Newfoundland (Toronto, 1971). W. G. Reeves, “The Fortune Bay dispute: Newfoundland’s place in imperial treaty relations under the Washington treaty, 1871–1885” (ma thesis, Memorial Univ. of Nfld, 1971). G. F. G. Stanley, “Further documents relating to the union of Newfoundland and Canada, 1886–1895,” CHR, 29 (1948): 370–86. F. F. Thompson, The French Shore problem in Newfoundland: an imperial study (Toronto, 1961). Twentieth-century Newfoundland: explorations, ed. J. [K.] Hiller and P. [F.] Neary (St John’s, 1994). Fred Vallis, “Sectarianism as a factor in the 1908 election,” Newfoundland Quarterly (St John’s), 70 (1974), no.3: 17–28. Whitbourne, Newfoundland’s first inland town: journey back in time – 1884–1984, comp. J. S. R. Gosse (Whitbourne, Nfld, 1985). W. V. Whiteway, Duty’s call: Sir W. V. Whiteway states his position (St John’s, [1904]).

Cite This Article

Melvin Baker and Peter Neary, “BOND, Sir ROBERT,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 15, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed January 1, 2026, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/bond_robert_15E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/bond_robert_15E.html |

| Author of Article: | Melvin Baker and Peter Neary |

| Title of Article: | BOND, Sir ROBERT |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 15 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 2005 |

| Year of revision: | 2005 |

| Access Date: | January 1, 2026 |