Source: Link

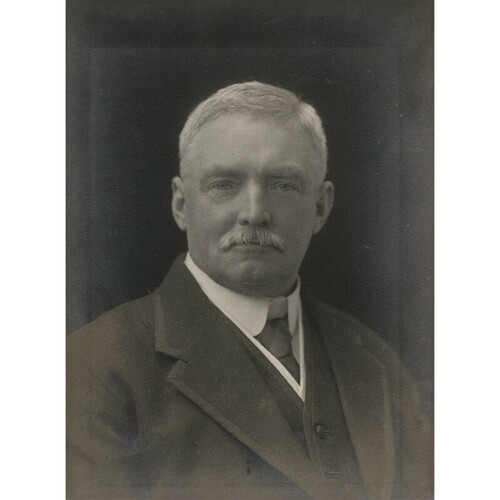

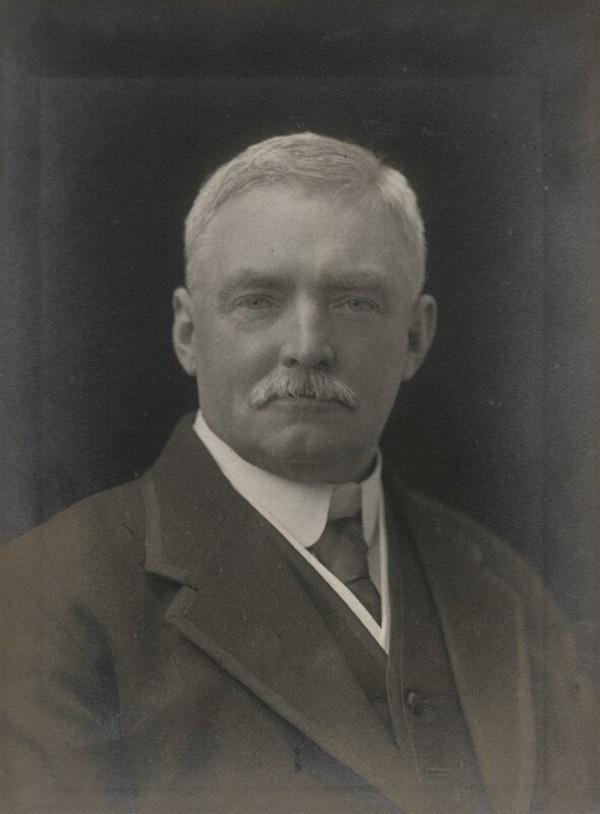

Lloyd, Sir William Frederick, teacher, solicitor, newspaperman, lawyer, and politician; b. 17 Dec. 1862 in Heaton Norris, Stockport, England, son of James Edward Lloyd, a machine fitter, and Emmeline (Emma) Downey; m. there 4 Jan. 1886 Agnes Margaret Taylor (1861–1911), a teacher, and they had two sons; d. 13 June 1937 in St John’s.

William Frederick Lloyd came from the upper levels of the English working class, his father being a skilled tradesman, probably involved in the local textile industry. Influenced by a teacher at his elementary school, Lloyd developed an interest in academic subjects, becoming a pupil-teacher. His formal education ended early, and he attended night and extension classes in mathematics and the sciences, first at a mechanics’ institute and later at institutions in Manchester and Newcastle upon Tyne. His teaching apprenticeship completed, he served at a number of schools in the Midlands and the north. While doing so, he registered at the University of London as an external student in 1884.

Lloyd moved to St John’s in 1890 to become a member of the staff in the boys’ department of the Church of England Academy (later Bishop Feild College). He was athletic and well liked, and became vice-principal in 1893. He had, however, decided on a legal career. He earned an llb from the University of London in 1894 and a bcl from Trinity College, Toronto, in 1898 (possibly ad eundem). Two years later he left teaching and in 1901 he received a dcl from Trinity. He articled in St John’s with the firm of Sir William Vallance Whiteway*, and in 1903 he was enrolled as a solicitor. He would not be called to the bar until 1916.

In January 1904 Lloyd, who had become active in the Liberal Party, took over from Alexander A. Parsons as editor of the Evening Telegram, a daily newspaper that supported the Liberal government of Sir Robert Bond*. The position made him an important player in the highly partisan and at times vicious rough and tumble of local politics. He was elected to the House of Assembly for Trinity Bay that fall in a contest that was won by the Liberals over a weak United Opposition Party.

The political scene had changed by the time of the next election in 1908. The government now faced the People’s Party, an anti-Bond combination put together by Sir Edward Patrick Morris, who had left the Liberals the previous year, and backed by the Reid railway interest [see Sir Robert Gillespie Reid*; Sir William Duff Reid*]. The poll resulted in a tie. Defeated in Port de Grave, Lloyd lost again in the 1909 run-off election, this time in Fortune Bay. In both instances he seems to have been a last-minute candidate. Morris’s victory in 1909 marked the beginning of the end for the Liberal Party. Bond was a reluctant opposition leader, there was no obvious successor, and the party was vulnerable to inroads from the Fishermen’s Protective Union of Newfoundland (FPU), led by William Ford Coaker. The Unionists opposed Morris, but insisted on maintaining their separate identity.

Lloyd had known Coaker since the 1890s, when he had tutored him privately, and was sympathetic to the union’s aims. (In 1898 he promoted a short-lived revival of the Newfoundland Teachers’ Association [see James Frederick Bancroft*].) He and other senior Liberals promoted an alliance with the FPU to fight the next election under Bond’s leadership. Lloyd was active in the ensuing negotiations, which were protracted and difficult. An uneasy agreement eventually emerged in late August 1913, shortly before that year’s poll. Lloyd won a seat in Trinity Bay (defeating Richard Anderson Squires), one of only 7 successful Liberals; the FPU took 8 seats and the People’s Party 21. Bond resigned in disgust. James Mary Kent was leader of the Liberal Party and of the opposition until his appointment to the bench in 1916. Lloyd then took over both positions. He headed the Liberal-Union Party after the opposition parties merged in March, and three months later he stepped down as editor of the Evening Telegram.

By this time World War I dominated public life. Overt party conflict had initially been pushed underground, but by 1917, officially an election year, it was resurfacing. Divisive issues faced the government, and after prolonged manoeuvring Morris struck a deal with the opposition parties to extend the life of the assembly and form a national government, which took office on 17 July. Lloyd became minister of justice and attorney general. When the session closed, Morris departed for London, leaving Lloyd in charge. Only he and Coaker were aware that Morris was escaping for good. By early January 1918 it was common knowledge that Morris had given up his office and accepted a peerage. On 5 January Lloyd became prime minister. Former Morris supporters who objected to this development resigned from the Executive Council and became the nucleus of an unofficial but vocal opposition.

It is unlikely that Lloyd wanted to be prime minister. Reserved and private by nature, he had lost his elder son in 1910 and his wife a year later. He was not personally ambitious, preferring to work in the background, where he could use his pen and other talents without undue prominence. Not an effective electoral campaigner, he came to dislike political intrigue and infighting. It was said – by Governor Sir Charles Alexander Harris, for one – that on occasion he drank too much. He performed well in the legislature, however, and Coaker described him as “the ablest Chairman of Council that I have been associated with.” Lloyd no doubt agreed to take the position from a sense of duty. The war had to be brought to a successful conclusion, and he was the most acceptable candidate if the National government, composed of old political enemies, was to survive. It was under his administration that the government, amidst increasingly strident controversy and criticism, pushed through conscription, imposed press censorship, further extended the life of the assembly, and raised more war loans.

As prime minister, Lloyd represented Newfoundland at meetings of the Imperial War Conference and imperial war cabinet, which, having been instituted in the spring of 1917, resumed in June 1918. It was, apparently, his first visit to London, and he was made a privy councillor. Recalled to Britain after the November armistice, he attended further war-cabinet meetings, and then the Paris Peace Conference early in 1919. His participation was low-key and unassertive. He may well have been preoccupied by the political situation at home, and by serious problems facing Newfoundland fish exporters in Italy [see Sir John Chalker Crosbie]. Nevertheless, he cannot shoulder the entire blame for the fact that Newfoundland was the only dominion to be denied separate representation at the conference and not to become a founding member of the League of Nations. Although he was no doubt insufficiently forceful, Newfoundland’s demotion was the result of a deal between the British and American governments that allowed the representation of the other dominions and India. The award to him of a kcmg in January 1919 (like the earlier privy councillorship) was greeted with some coolness by his colleagues in Newfoundland, but Lloyd understood that the honour primarily recognized the colony and his office.

Cutting short his stay at the peace conference, Lloyd arrived back in mid March 1919. The legislature, which was supposed to expire on 30 April, opened soon afterwards. The National government intended to go to the country as a unit and wanted to make provision for a spring election. Fierce criticism forced it to postpone the vote until the autumn, however, and as the controversy continued the administration began to fall apart. The debate about its future that had begun with the armistice had led to deep disagreements over the way forward. Coaker wanted Lloyd to renounce the People’s Party, and his aggressive manoeuvring offended coalition partners. At the same time there was strong pressure from Archbishop Edward Patrick Roche* on Roman Catholic members of the government to abandon the FPU. Their leader, Sir Michael Patrick Cashin*, tried through an intermediary to persuade Lloyd to repudiate Coaker and the Unionists. Lloyd refused.

Knowing Lloyd’s position, Cashin resigned as minister of finance on 20 May, and when the assembly reconvened shortly thereafter he moved that it adjourn and “place on record its opinion that the Government as at present constituted does not possess the confidence of the House.” Lloyd informed the legislature that he had already submitted his resignation to the governor and that a no-confidence vote was unnecessary: he would willingly step down. Nevertheless, the speaker asked for a seconder. After a long pause, Lloyd supported the motion. The National government swiftly disappeared, and Cashin became prime minister two days later.

This curious incident, in which the participants’ actions were largely symbolic, has become locally famous. Lloyd is remembered chiefly because he is thought to be the only prime minister to second a no-confidence motion aimed at his own government. His move was in fact astute, a point that Governor Harris recognized. The “burlesque” – as one newspaper called it – confirmed that the National government was finished, handed the premiership to Cashin (who may not have wanted it at this time), and signalled that Lloyd was leaving public life, as he wished. He refused to lead the opposition, which would coalesce around R. A. Squires. When the new government appointed him registrar of the Supreme Court of Newfoundland, Coaker bitterly charged that Lloyd had been bribed into retirement and silence, an accusation that Lloyd convincingly rebutted in the house.

Lloyd remained registrar until his death. He resisted requests to return to public life, though he served as minister of justice in Albert Edgar Hickman*’s month-long government in 1924, likely because Hickman was a former political ally. He was secretary of the Law Society of Newfoundland, and in this capacity instructed, assisted, and examined law students. He also administered workers’-compensation payments, sometimes helping needy families from his own means.

Lloyd appears to have been a respected figure, all of his obituaries mentioning his integrity, intelligence, and capacity for hard work. Nevertheless, he cannot be said to be one of Newfoundland’s outstanding prime ministers. Reluctant to accept the office, he handled competently some difficult and bruising issues, and for these achievements he deserves credit. But he was not an effective leader, and his performance in London and Paris at the end of the Great War remains controversial, though he was obviously steamrollered by the British government. Still, it was, after all, a long way from Stockport and a mechanics’ institute to the Privy Council and a knighthood.

RPA, GN 8 (Office of the Prime Minister fonds), William Frederick Lloyd sous fonds. Daily News (St John’s), 14, 15 June 1937. Evening Herald (St John’s), 1919. Evening Telegram (St John’s), 1919, 14 June 1937. Fishermen’s Advocate (St John’s and Port Union, Nfld), 18, 25 June 1937. S. T. Cadigan, Death on two fronts: national tragedies and the fate of democracy in Newfoundland, 1914–34 (Toronto, 2013). P. J. Cashin, Peter Cashin: my fight for Newfoundland, a memoir, ed. Edward Roberts (St John’s, 2012). W. F. Coaker, Past, present and future: being a series of articles contributed to the “Fishermen’s Advocate,” 1932; together with notes of a trip to Greece 1932 ([Port Union, 1932]). H. A. Cuff, A history of the Newfoundland Teachers’ Association, 1890–1930 (St John’s, 1985). W. C. Gilmore, Newfoundland and dominion status: the external affairs competence and international law status of Newfoundland, 1855–1934 (Toronto, 1988); “Newfoundland and the Paris Peace Conference, 1919,” British Journal of Canadian Studies (Edinburgh), 1 (June–December 1986): 282–301. I. D. H. McDonald, “The reformer Coaker: a brief biographical introduction,” in The book of Newfoundland, ed. J. R. Smallwood et al. (6v., St John’s, 1937–75), 6: 71–96; “To each his own”: William Coaker and the Fishermen’s Protective Union in Newfoundland politics, 1908–1925, ed. J. K. Hiller (St John’s, 1987). D. F. MacKenzie, “‘Not a politician, but … a statesman’? William Lloyd, prime minister of Newfoundland, 1918–1919” (St John’s, 2002; research paper in author’s possession). Nfld, General Assembly, Journal, 1919; Proc., 1919. S. J. R. Noel, Politics in Newfoundland (Toronto, 1971). P. R. O’Brien, “The Newfoundland Patriotic Association: the administration of the war effort, 1914–1918” (ma thesis, Memorial Univ. of Nfld, St John’s, 1981). Patrick O’Flaherty, Lost country: the rise and fall of Newfoundland, 1843–1933 (St John’s, 2005). Twenty years of the Fishermen’s Protective Union of Newfoundland from 1909–1929 …, comp. W. F. Coaker (St John’s, 1930).

Cite This Article

James K. Hiller, “LLOYD, Sir WILLIAM FREDERICK,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 16, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed December 21, 2024, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/lloyd_william_frederick_16E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/lloyd_william_frederick_16E.html |

| Author of Article: | James K. Hiller |

| Title of Article: | LLOYD, Sir WILLIAM FREDERICK |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 16 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 2021 |

| Year of revision: | 2021 |

| Access Date: | December 21, 2024 |