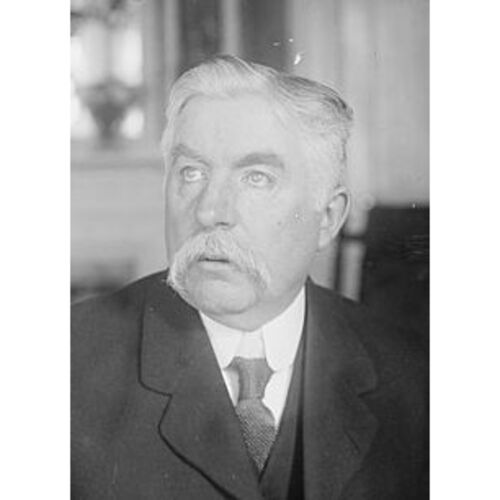

Source: Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

MORRIS, EDWARD PATRICK, 1st Baron MORRIS, teacher, lawyer, editor, and politician; b. 8 May 1858 in St John’s, fourth of the six children of Edward Morris and Catherine Fitzgerald; m. 19 Jan. 1901 Isabel Langrishe LeGallais (d. 1 July 1934), widow of politician James Patrick Fox, and they had a son; d. 24 Oct. 1935 in London, England.

Edward Morris’s parents were from Ireland; his father, a cooper, eventually became superintendent of the St John’s Poor House. Despite this relatively humble background, Morris attended St Bonaventure’s College in St John’s, which provided one of the best educations available in the colony, and he and his four brothers had successful careers. Morris left school in 1874 and for the next four years taught at a school established by his elder brother, Father Michael Morris, at Oderin in Placentia Bay. Between 1878 and 1880 he studied at the high school attached to the College of Ottawa (now the University of Ottawa), and possibly at the college itself. He then returned to St John’s, where he prepared to take an active part in political life by founding Academia, a young men’s club, in 1882, and training for the law with James Spearman Winter*. He was admitted as a solicitor in 1884; called to the bar in 1885, he soon afterwards started a law firm with his brother Francis J. Morris.

In that year’s general election Morris ran as an independent candidate in the three-member district of St John’s West, a largely working-class, Roman Catholic constituency. He canvassed door to door, then an unusual practice, promoted himself as a champion of the underdog, and topped the poll. Until the end of his career in Newfoundland, Morris was impregnable in St John’s West. A superb and indefatigable local politician, blessed with an affable personality, a fluent tongue, and an impressive memory, he was re-elected there ten times.

In the House of Assembly, Morris sat in opposition to the Reformers led by Robert Thorburn*. He advocated social legislation for fishermen and other workers, supported electoral and local-government reform, and declared that railway building was the key to Newfoundland’s economic future. Not surprisingly, he gravitated towards the party being put together by Sir William Vallance Whiteway*, Robert Bond*, and Alfred Bishop Morine* to fight the 1889 election. Calling itself Liberal, the party resurrected from the 1882 campaign Whiteway’s “Policy of Progress,” whose centrepiece was the completion of the railway begun in 1881. Whiteway won a large majority and appointed Morris, without portfolio, to the Executive Council, thus recognizing his influence in St John’s and bolstering Roman Catholic representation in the government.

Throughout the politically stormy years that followed, Morris was not a prominent player. He tended a lucrative law practice which owed some of its prosperity to plentiful government work (he would be made a qc in 1896), acted as attorney general when Whiteway was absent, handled law bills, and busied himself with municipal affairs; during the 1890s he would also edit five volumes of the Newfoundland Law Reports (St John’s, 1897–1901). He supported the administration’s policy in general, and took few chances. Like most government members he was unseated early in 1894 on the grounds of corrupt practice in the election of the previous year, but he was re-elected in February 1895.

Within a month Morris faced a potentially uncomfortable situation when he was appointed to a delegation to Ottawa (led by Bond, who was colonial secretary) to ascertain the feasibility of confederation. He had spoken against confederation in 1888, and most of his constituents were anti-confederate. Now, however, Newfoundland was in severe financial difficulty following the collapse of its two private banks in December 1894 [see James Goodfellow*], and it seemed that the only alternative might well be bankruptcy and the surrender of responsible government. The negotiators could not agree about monetary issues, and Morris announced failure to the house on 16 May.

The colony survived the crisis thanks to loans raised by Bond, but financial retrenchment contributed to the Liberal defeat in the 1897 election. Whiteway lost his seat and Bond became the party’s leader in the house. The following year, along with four supporters, including Michael Patrick Cashin*, Morris broke with Bond, an action that confirmed his emergence as an important political chieftain. The issue was a new railway contract between James Spearman Winter’s Tory government and Robert Gillespie Reid*. He had built most of the transinsular line, now completed, after signing construction and operating contracts with the Whiteway administration in 1890 and 1893. The new contract specified that Reid would operate the railway for 50 years and it would then become the property of his heirs. For operation, he was to receive additional land grants, and he was to pay $1 million for the reversionary interest. Reid also undertook to purchase other government franchises, such as the dry dock. Morris was close to the Reid family and saw in the arrangement some immediate financial relief, the promise of jobs in St John’s West, and substantial economic progress with little risk. Bond regarded the contract as immoral chicanery and campaigned effectively against it.

By early 1900 the Winter administration was nearing collapse. Morris apparently feared that if Bond became premier, the Reid deal and its supporters might be sent into oblivion. Astutely seconding Bond’s motion of no-confidence, he helped bring the government down on 19 February. He then formed an alliance with Bond that safeguarded the essence of the Reid contract and his own political future: he became a minister without portfolio in the new Liberal government, which was confirmed in office by an election in November.

Morris was genial and outgoing, Bond reserved and aloof; each was wary of the other, and Bond deeply mistrusted Morris because of his links with the Reids. A 1901 compromise on the 1898 contract, which among other things relieved Reid of his reversionary interest in the railway, was described by Morris as “fair”; nevertheless, he regarded it as a mistake. Ambitious yet cautious, he did not immediately challenge Bond’s leadership. He became minister of justice in 1902 and was knighted in 1904 (he would be appointed a kcmg in 1913). After the 1904 election Bond’s popularity declined as he became increasingly obsessed by a complex fisheries dispute with the United States. He made enemies in London and Ottawa, and his feud with the Reids, inflamed by another clash in 1905, reached a climax. Not surprisingly, those whom Bond had exasperated began to consider Morris the only politician who could challenge the prime minister.

Supported by journalist Patrick Thomas McGrath* and discreetly funded by the Reids, Morris made his move in July 1907. Using a pretext, he resigned from his portfolio and the Liberal Party to sit as an independent opposition member. In March 1908 he launched the People’s Party, a coalition of Morris loyalists, disaffected Liberals, and leftover Tories. His comprehensive list of some 30 promises included reduced taxes, education reform, and branch railways. He set about attacking the government of which he had so recently been a member, and campaigned energetically. The result of the November general election was a tie between the two parties.

In the ensuing constitutional and political crisis Bond played his cards badly and Morris played his to advantage. On 22 Feb. 1909 the premier submitted his resignation when the governor, Sir William MacGregor, rejected his advice to dissolve the house. MacGregor, who disliked Bond, asked Morris whether he could form a ministry “with a reasonable prospect of being able to induce Parliament to pass Supply.” Morris brazenly replied that he could, and took over on 3 March, the day Bond’s resignation came into effect. When the house met on 30 March, it proved impossible to choose a speaker since neither party could afford to lose a member, and MacGregor granted Morris a dissolution. After a bitter election campaign, the People’s Party won a 16-seat majority despite the strong pro-Bond stance of the Roman Catholic archbishop of St John’s, Michael Francis Howley*, who was virulently anti-Reid.

The Morris administration of 1909–13 was fortunate to be in office during an economically buoyant period. Fish prices were good. Employment was generated by the Bell Island iron mines [see Thomas St John*] and the development of the pulp and paper industry in Grand Falls [see Harry Judson Crowe*]. More jobs were created by the fulfilment of Morris’s promise to build branch railway lines, the contract being awarded, without tender, to the Reid Newfoundland Company, now headed by William Duff Reid*. Though popular, the lines could not be made profitable and would be largely responsible for increasing the public debt by over 30 per cent during the government’s tenure. Until 1913–14, however, there would be a small annual surplus on current account despite greater spending on education, public health, the telegraph system, and local steamer services, and the introduction of a limited old-age pension in 1911.

One of Morris’s first actions was to pass legislation incorporating the Newfoundland Board of Trade (June 1909). He hoped that this association would be the means of reforming and modernizing the fishing industry. There was broad agreement about what needed to be done, but friction soon developed between the government and the merchants over their respective spheres of responsibility. The argument was complicated by the Fishermen’s Protective Union of Newfoundland, founded in 1908 by William Ford Coaker. The union distrusted the board, and urged the government to intervene more energetically in the industry. Reluctant to alienate either side, Morris made himself unpopular with both. Since relative prosperity blunted any sense of urgency, extensive fisheries reform was postponed.

Morris, however, was not inactive. He once said that “the governing of a nation is like a great commercial enterprise – its success depends on advertising its wares,” and he went to great lengths to attract new industries to Newfoundland. Convinced that cold-storage depots for fish were essential, he devoted a great deal of time to unsuccessful attempts to induce businessmen to develop the industry. He tried and failed to persuade firms to manufacture glue and fertilizer from fish offal, supported experiments in exporting fresh fish to mainland markets, and urged, without result, the British navy to place Newfoundland fish on its menus. His administration shared the colony’s growing concern about fish stocks and safety issues when French steam trawlers began to arrive on the offshore banks, and he pressed the imperial government to hold an international conference. Morris also attempted to improve fish sales: he lobbied for closer trade ties with the British West Indies, expressed interest in a reciprocity treaty with the United States, and appointed trade commissioners in Europe. Other possibilities were not neglected. There was considerable emphasis on agriculture and sheep farming, and businesses were encouraged to develop the island’s peat bogs and what optimists believed to be substantial reserves of coal, oil, and copper. The government even backed programs for manufacturing explosives and exporting beach rocks.

Believing such economic achievements to be overwhelmingly important, Morris was willing to make legislative, financial, and territorial concessions for grandiose schemes: he had brushed aside questions about the lack of tenders for the branch railway lines with the demand, “What do I care for the Audit Act when there are people in need of bread?” Increased interest in the potential of Newfoundland and Labrador forests was fuelled by changes in the American tariff that reduced or eliminated charges on wood and wood products and 1911 amendments to the Crown Lands Act that made it easier for speculators to acquire public land. A wave of speculation in timberlands aroused much domestic criticism, especially after it became known in April 1912 that Minister of Justice Donald Morison, who had steered the legislation through the house, held shares in an American company that had been granted timber rights over 13,853 square miles in Labrador. The conflict of interest went unpunished.

Imperial officials welcomed a cooperative prime minister (the title Morris began to use in 1909) who enthusiastically voiced loyal sentiments. The Newfoundland government’s handling of the North Atlantic fisheries arbitration at The Hague in 1910 (the colony was represented by Winter) did not pass without criticism in London, but Morris, who could be a tough negotiator, played a competent role in arranging the award’s implementation. At the Imperial Defence Conference in 1909 he suggested that Newfoundlanders could crew the British navy’s new Dreadnoughts; at the 1911 Imperial Conference he promoted Newfoundland as part of the All-Red Route, a plan for transportation intended to connect Britain to its possessions in the Far East via land and sea.

Yet overall, despite his energy and quite genuine desire to bolster his country’s interests, Morris’s first administration was short on tangible achievement. Businessmen disliked his free-spending ways; Coaker, outraged by Morris’s failure to move on fisheries reform or rein in timber speculators, led the FPU into an uneasy, tense coalition with Bond and the Liberals. The coalition was unable to function effectively in the 1913 election campaign and failed to present itself as a viable alternative to the People’s Party. Nevertheless, Morris recognized the threat posed by the FPU, and played on fears of “socialism” and “godless schools.” His party lost some seats, mainly as a result of the union’s influence, but it retained a majority.

The session that opened in the spring of 1914 illustrated the political problems that Morris now faced. Although Bond had resigned and James Mary Kent had become leader of the weakened Liberals, union representatives dominated the opposition and pursued their reform agenda with some success. The prime minister chose a loyal supporter, Richard Anderson Squires, as justice minister and attorney general and appointed him to the Legislative Council; however, conservative members struck down legislation they found offensive, even if government sponsored. There was widespread concern about public finances, and Morris was under pressure from the Reid family to help them abandon the financial mess that was the railway, preferably through confederation with Canada. Although “no confederation” had been one of his 1908 campaign promises, Morris now told Governor Sir Walter Edward Davidson that he had “no clearly defined views on it.” He had, in fact, been flirting with confederation for some time. In 1911 Prime Minister Sir Wilfrid Laurier* had privately and unofficially offered generous terms; these had been rejected, but by 1914 Edward Michael Jackman*, a former member of Bond’s government now in alliance with Morris, and Arthur Meighen*, the Canadian solicitor general, were holding subterranean talks, and Morris and the Reids were among those manoeuvring to bring Coaker and the FPU into agreement. The outbreak of World War I in August 1914 did not end these discussions, but certainly complicated them.

All parties endorsed Newfoundland’s participation in the war, which was administered until 1917 by a unique expedient. Davidson persuaded Morris to convene a public meeting from which emerged the Patriotic Association of Newfoundland, a non-partisan volunteer body intended to ensure that religious and political divisions would not hinder the war effort. Chaired by Davidson, it acted as a militia department, funded mostly by the government. Morris probably hoped that the apparent unity would divert attention from domestic problems and avoid the need for a coalition government.

The war caused a boom in fish sales, and by 1916 Coaker had backed away from confederation (as had the Canadian government). Yet the war also brought serious problems. The financial strain of supporting the Newfoundland Regiment was considerable, taxes had been raised, inflation arrived with a vengeance, and there was a chorus of complaint about profiteering. The regiment suffered appalling losses on the Western Front [see Francis Thomas Lind*; Owen William Steele*], and the spectre of conscription haunted strident and ineffective recruitment drives. Divided authority and political wrangling in the legislature made decisive action almost impossible, as did the prime minister’s absences. During the summer of 1916 he was in Europe, and when invited in late December to attend the first meetings of the newly formed imperial war cabinet, to be held in London in March 1917, he accepted without hesitation.

Morris returned on 20 May and finally took charge. There was supposed to be an election that year, but he had no intention of facing voters if he could avoid it. The opposition, an alliance of Liberals and Unionists led by William Frederick Lloyd, scented blood. The prime minister let it be known that he would introduce legislation postponing the election, and then negotiated a coalition government, which took office on 17 July. During a rushed session the house replaced the Patriotic Association of Newfoundland with the Department of Militia, and drew up a bill to tax business profits that was initially refused by the Legislative Council. The bill was amended and then passed, together with a restriction on the council’s powers, after Morris had added new appointees. He went back to England in September, leaving Lloyd as acting prime minister. In a letter dated 19 November he resigned as prime minister, party leader, and house member; the resignation was accepted 2 Jan. 1918. The news became public on Christmas Eve, and on 5 January it was learned that, on Davidson’s recommendation, he had been elevated to the House of Lords as Baron Morris of St John’s in the Dominion of Newfoundland, and of the City of Waterford.

Morris’s actions caused consternation, especially among his former supporters. While declaring that he would not desert the government, he had secretly promised Lloyd and Coaker that he would resign by the end of the year. He was roundly denounced for betrayal, duplicity, selfishness, and guile, and for delivering the country into the hands of Coaker and his socialistic rabble. News of his peerage was greeted in some quarters with ridicule, but by and large the public accepted it as a tribute to the regiment and to Newfoundland.

Thereafter Morris returned only for short visits. He was always ready to champion Newfoundland, however, and he took an active interest in imperial affairs. The fury of his abandoned followers thwarted his hope of winning the job of high commissioner, but the contacts he had made during his many trips to London yielded a number of directorships, and he served on the boards of educational institutions and philanthropic organizations. His life in London was a world away from his childhood on Limekiln Hill (Lime Street) in St John’s.

In 1933 some witnesses who appeared before the Newfoundland royal commission [see Frederick Charles Munro Alderdice] claimed that their country’s descent into the crisis it then faced could be dated from 1909, when Morris had become prime minister. This judgement is not altogether fair. Morris was a shrewd, skilled, and intelligent politician. His policies were not so very different from those of Bond and Whiteway, and his views on issues such as the French Shore problem were conventional. He shared prevailing imperial enthusiasms, though his emphasis on imperial federation was perhaps unusual. He was in many ways a conservative, once telling Coaker that “great caution must be exercised in bringing about changes which largely affect the masses, the more especially when those changes are of a radical nature, and mean the altering of systems and institutions which at least have the recommendation of having stood the test of time.” Yet he was willing to promise whatever was needed to achieve and keep power, and spent accordingly. Heavily influenced by the Reids, he was also prepared to grant whatever inducements were necessary to attract investment. Neither a strong nor a particularly principled leader, he tolerated and defended sharp practice. In 1917 he abandoned his government at what was, for Newfoundland, the most difficult stage of the war, leaving a political legacy of post-war instability.

NA (G.B.), CO 194; CO 537. RPA, GN 8, Edward Patrick Morris sous fonds. Daily News, 25 Oct. 1935. Times (London), 25 Oct. 1935. Melvin Baker, “The government of St John’s, Newfoundland, 1800–1921” (phd thesis, Univ. of Western Ont., London, 1980). A. M. De Beck, The imperial war: personalities and issues … (London, 1916). G.B., Nfld royal commission, Report (London, 1933). J. P. Greene, “Edward Patrick Morris, 1886–1900” (history dissertation, Memorial Univ. of Nfld, St John’s, [1968]). J. [K.] Hiller, “A history of Newfoundland, 1874–1901” (phd thesis, Univ. of Cambridge, Eng., 1971); “The political career of Robert Bond,” in Twentieth-century Newfoundland: exploration, ed. J. [K.] Hiller and P. [F.] Neary (St John’s, 1994), 11–45. R. G. Hong, “‘An agency for the common weal’: the Newfoundland Board of Trade, 1909–1915” (ma thesis, Memorial Univ. of Nfld, 1998). I. D. H. McDonald, “To each his own”: William Coaker and the Fishermen’s Protective Union in Newfoundland politics, 1908–1925, ed. J. K. Hiller (St John’s, 1987). L. C. Murphy, “The late Lord Morris: a war-time tribute,” Newfoundland Quarterly (St John’s), 35 (1935–36), no.3: 16. S. J. R. Noel, Politics in Newfoundland (Toronto, 1971). P. R. O’Brien, “The Newfoundland Patriotic Association: the administration of the war effort, 1914–1918” (ma thesis, Memorial Univ. of Nfld, 1981). Patrick O’Flaherty, Lost country: the rise and fall of Newfoundland, 1843–1933 (St John’s, 2005).

Cite This Article

James K. Hiller, “MORRIS, EDWARD PATRICK, 1st Baron MORRIS,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 16, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed December 21, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/morris_edward_patrick_16E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/morris_edward_patrick_16E.html |

| Author of Article: | James K. Hiller |

| Title of Article: | MORRIS, EDWARD PATRICK, 1st Baron MORRIS |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 16 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 2015 |

| Year of revision: | 2015 |

| Access Date: | December 21, 2025 |