Source: Link

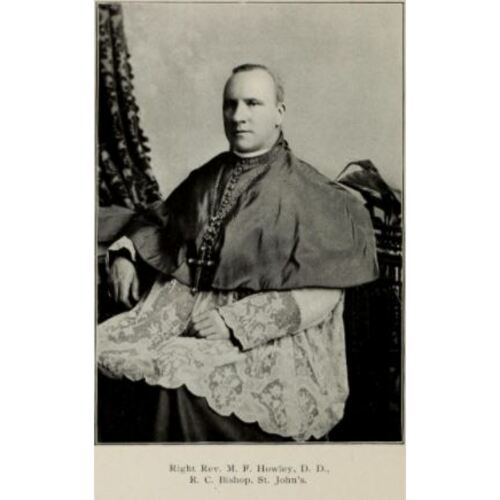

HOWLEY, MICHAEL FRANCIS, Roman Catholic priest, archbishop, and author; b. 25 Sept. 1843 in St John’s, son of Richard Howley and Eliza Burke; d. there 15 Oct. 1914.

Michael Howley was a member of a distinguished Newfoundland family. His father, who had emigrated from Ireland in the early 19th century, was a successful merchant and civil servant. Among his brothers, Thomas* became a doctor and James Patrick a geologist and author. Michael received his early education at the Roman Catholic academy in St John’s, directed by John Valentine Nugent*. At the age of 13 he enrolled in the Catholic college established under Enrico Carfagnini* in the old episcopal palace, and when in 1858 it reopened as St Bonaventure’s College, he was among its first students. At St Bonaventure’s he received a sound classical education. He left there in 1863 to study for the priesthood at the Urban College of the Sacred Congregation of Propaganda in Rome.

Howley was ordained priest at the Church of St John Lateran on Trinity Sunday, 6 June 1868. Immediately after, he was chosen by Propaganda to serve as secretary to Charles Eyre, the newly appointed apostolic delegate and administrator of the western district of Scotland. Howley remained in Scotland for 15 months, until he returned with Eyre to Rome to attend the first Vatican Council. Events leading up to and during this contentious and definitive council had an enormous impact on Howley and were to influence his thinking for the rest of his life. It was during this period that his fundamental conservatism was confirmed. While in Rome he obtained his doctoral degree from the cardinal prefect of Propaganda.

Thomas Joseph Power*, who had just been consecrated bishop of St John’s, was also present at the council, and he asked Howley to return with him to Newfoundland. Howley’s first assignment after his arrival at St John’s in September 1870 was to serve at the Cathedral of St John the Baptist. During the summer months between 1871 and 1873 he assisted Thomas Sears, prefect apostolic of St George’s on the island’s west coast. In 1876 he was appointed parish priest of Fortune Bay and remained there for three years. He then returned to St John’s as assistant priest at the cathedral. When in 1885 Sears became ill, Howley was sent to assist him as administrator of St George’s. He took the unusual step of requesting that he be named to succeed Sears when the prefect retired. Sears died later that year, and Howley was appointed in his place. He was confirmed in his new position in July 1886.

The west coast of Newfoundland was underdeveloped, accessible only by boat, and peopled with a diverse population scattered over a vast geographic area. Remote both from Rome, under whose jurisdiction he served, and from church authorities in St John’s, Howley was able to function with a great deal of autonomy. His years in St George’s were arduous and challenging. The physical hardships he endured are known only from the reports of contemporaries. His diaries make no reference to the difficulties of travelling throughout this huge territory or of the primitive living conditions. During his stay on the west coast, he entered into the social, economic, spiritual, and political life of the area both as a public figure and in his capacity as pastor. He obtained the services of the Sisters of Mercy from Rhode Island, for whom he erected a convent, he built churches in a number of places, and he improved schooling for the children. He was admired in the ethnically diverse region [see Constant Garnier*] because of his ability to speak French and Gaelic.

Like many others in Newfoundland, Howley resented the fishing rights granted the French on the so-called French Shore under the Treaty of Utrecht (1713), viewing them as unjust to the local inhabitants. When the issue became an openly political one in 1890–91, following the signing of an Anglo-French modus vivendi governing the lobster fishery [see James Baird; Sir William Vallance Whiteway*], Howley involved himself publicly and privately with all levels of government, British, French, and colonial. He even went so far as to request Pope Leo XIII to intervene. He acted as the principal spokesman for the people of the west coast, and his actions may have contributed to the eventual resolution of the issue. They certainly led to pressure being put by the British government on politicians in St John’s to improve the lot of Newfoundlanders living on that coast.

In 1892 St George’s was elevated by papal bull to a vicariate apostolic, and Michael Howley was elected vicar apostolic and titular bishop of Amastris. He was consecrated by Bishop Power in St John’s on 24 June, becoming the first native-born Newfoundlander raised to the episcopacy. He returned to St John’s in late 1894 to become the bishop of that diocese, succeeding Power, who had died the previous year. At his urging and that of Bishop Ronald Macdonald of Harbour Grace, Newfoundland was created an ecclesiastical province in 1904. At the same time St John’s was raised to an archdiocese, and Howley became its first archbishop.

For 20 years, as bishop and archbishop, he worked to meet the spiritual, social, and educational needs of the people of St John’s. He restored the cathedral and introduced electric lights. He encouraged the improvement of educational facilities for Catholic children and expanded St Bonaventure’s College for men and St Bride’s Academy, Littledale, now a college for women. Howley placed great emphasis on education because he believed it would provide the opportunity for Catholics to advance in the modern world. He was most concerned about the education of young men. In 1898, when young women in the convent schools excelled in public examinations, he felt they had proved their ability and decreed that they should now return to studies which would make them better wives and mothers. To meet the needs of the less fortunate, he arranged the transfer of the family home, Mount Cashel, to the Brothers of the Christian Schools of Ireland as an orphanage and training school for boys under the direction of John Luke Slattery*.

Howley did not reserve all his energies for spiritual matters. He also concerned himself with the economic and political life of the colony. When the railway contract of 1898 gave virtual control of the economy to Robert Gillespie Reid* and his family, the bishop mounted a vigorous public campaign to help defeat the contract, crossing political and religious barriers to do so. In a letter to Governor Sir Herbert Harley Murray*, he threatened to advise people to withdraw their money from the Newfoundland Savings Bank if the governor signed the railway bill, and he wrote in a similar vein to Premier Sir James Spearman Winter. The contract was eventually revised. Howley took an active part in local politics, using his considerable influence to support the candidates and party of his choice. He attended public meetings, wrote to the press, and embroiled himself in controversies, sometimes allowing his enthusiasm for a cause to cloud his judgement. The full impact of his involvement remains an open question, but politicians were reluctant to test his power.

When the British doctor Wilfred Thomason Grenfell*, who had begun a mission to the fishermen of Labrador and northern Newfoundland in 1892, raised large sums of money in the United States and Canada by describing the living and working conditions of the people, Howley and others in the colony reacted with anger. He openly criticized the mission in a series of letters to the Daily News in December 1905. Not only was it unnecessary, but “the means by which Dr. Grenfell obtains financial aid for his Mission is A Degradation of the People of Newfoundland.” The slides which the doctor used to illustrate his lectures, “taken from the very lowest and poorest of our people’s homes, are highly colored by an exaggerated verbal description, and the impression left on the mind of the hearers is that such is the general and Normal State of Our People. Thus the poverty of a few . . . of our poorest settlements is exploited as a means of extracting alms from a charitably-minded audience.” Grenfell was also in the habit of describing the difficulties he had personally experienced in the course of his work. Howley, who had laboured in similar conditions on the west coast, wondered why the self-proclaimed missionary did not simply carry on his chosen work without complaint.

The archbishop believed that he had a responsibility to address every aspect of the lives of the people he served and to help them make wise decisions. Throughout his life his sermons reflect the changing concerns of society. An ultra-conservative, he challenged the impact of the new social order in the world, viewing the struggle of working people to improve their lot as a threat to his and the church’s authority. When William Ford Coaker* started the Fishermen’s Protective Union in 1908, Howley vigorously opposed him. He banned Catholic fishermen from joining the FPU on the grounds that its oath of loyalty made it a secret society and therefore forbidden by the church. More profoundly, in a circular letter written in 1909, he made it clear that he believed the union threatened the church’s temporal authority and would set Catholic fishermen against Catholic merchants. Howley later rescinded the ban, but the damage had been done. The predominately Catholic fishing communities of the south shore never joined the union, and he thus contributed significantly to its ultimate failure.

Michael Howley was a passionate Newfoundland patriot and saw endless potential for the island. He designed the coat of arms of the city of St John’s, contributed to the contest to choose a national anthem, and wrote numerous articles praising Newfoundland for newspapers and journals around the world. In the preface to his Ecclesiastical history of Newfoundland (Boston), published in 1888, he tells how since his school days he had been collecting “everything in any way bearing on the past history of our country; every anecdote of the olden time; every scrap of manuscript; every inscription or epitaph . . . ; every vestige of the former occupation of Newfoundland, whether civil, military, or ecclesiastical.” Largely based on the work of earlier writers and an unpublished manuscript by Bishop John Thomas Mullock*, the history provides an account of the island from the earliest European contact to the death of Bishop Michael Anthony Fleming* in 1850.

In Poems and other verses (New York, 1903), Howley collected together work ranging from verses written at St Bonaventure’s to an operetta celebrating the golden jubilee of the arrival of the Presentation sisters in Newfoundland [see Miss Kirwan*, named Sister Mary Bernard], performed by school children in 1883. The volume also contains his patriotic poem popularly known as “Fling out the flag.” Among his other writings are treatises on the voyages of John Cabot* and Jacques Cartier* and the Viking settlement at Vinland. A supporter of the theory that Cabot had reached Newfoundland in 1497, Howley was part of a movement to commemorate the landfall, and on 22 June 1897 he laid the cornerstone for the Cabot Tower on Signal Hill [see Daniel Woodley Prowse]. For 14 years he contributed regular articles on the island’s place-names to the Newfoundland Quarterly, the last one appearing shortly after his death in 1914.

Archbishop Howley was a complex man. Although a great supporter of Newfoundland, when the government of the colony appeared to be neglecting the people of the west coast, he proposed that they join Canada. There were good reasons why they might contemplate such a change, since their economic, ethnic, and social ties with the mainland were strong. Later in his life Howley is said to have espoused confederation with Canada for the island as a whole. The extent of his involvement in such a movement remains unknown. He was accused in both instances of playing a political game. But as a frequent visitor to the Canadian mainland, he could perhaps have seen advantages for Newfoundland and the Catholic community in such a union.

An intelligent, vigorous man, Michael Howley served his people and his country with dedication throughout his life. He was a devoted churchman, an involved citizen, and a true patriot. Honoured by numerous learned societies during his lifetime, in 1902 he was elected fellow of the Royal Society of Canada. He died in October 1914 after a short illness and is buried in Belvedere Cemetery in St John’s.

Michael Francis Howley’s Ecclesiastical history of Newfoundland was reprinted at Belleville, Ont., in 1979.

Arch. of the Archdiocese of St John’s, M. F. Howley papers. G.B., Foreign and Commonwealth Office Library (London), Foreign Office, “Report of the Newfoundland royal commission . . .” (printed but unpublished confidential report, London, 1899; photocopy at Memorial Univ. of Nfld, St John’s). PANL, GN 1/3/A, 1886–1914; GN 1/3/B, 1886–95; GN 1/14/2. PRO, CO 194/120, CO 194/210. Colonist (St John’s), 1886–92. Daily News (St John’s), 1894–1914, esp. 5, 11, 13 Dec. 1905; 16 Oct. 1914. Evening Mercury (St John’s), 1882–90, continued as the Evening Herald, 1890–1914. Evening Telegram (St John’s), 1879–1914. Fishermen’s Advocate (Coakerville, Nfld; St John’s), 1910–14. Gazette (Montreal), 1898–1914. Glasgow Herald, 3 Dec. 1869. Morning Chronicle (St John’s), 1880–81. Royal Gazette and Newfoundland Advertiser (St John’s), 1889–1904. St. John’s Free Press, 9 April–6 July 1877. Times and General Commercial Gazette (St John’s), 1886–95. Michael Brosnan, Pioneer history of St. George’s diocese, Newfoundland ([Corner Brook, Nfld, 1948]). The centenary of the Basilica-Cathedral of St. John the Baptist, St. John’s, Newfoundland, 1855–1955, ed. P. J. Kennedy ([St John’s], n.d.). Encyclopedia of Nfld (Smallwood et al.). J. K. Hiller, “A history of Newfoundland, 1874–1901” (phd thesis, Univ. of Cambridge, Eng., 1971). I. D. H. McDonald, “To each his own”: William Coaker and the Fishermen’s Protective Union in Newfoundland politics, 1908–1925, ed. J. K. Hiller (St John’s, 1987). A. B. Morine, The railway contract, 1898, and afterwards: 1883–1933 (St John’s, 1933). Nfld, House of Assembly, Journal, 1886–1914. Newfoundland; economic, diplomatic, and strategic studies, ed. R. A. MacKay (Toronto, 1946). The peopling of Newfoundland: essays in historical geography, ed. J. J. Mannion ([St John’s], 1977). Ronald Rompkey, Grenfell of Labrador: a biography (Toronto, 1991). Thomas Sears, Report of the missions, prefecture apostolic, western Newfoundland, [ed. M(ichael) Brosnan] ([Corner Brook, 1943]). F. F. Thompson, The French Shore problem in Newfoundland: an imperial study (Toronto, 1971).

Cite This Article

Barbara A. Crosbie, “HOWLEY, MICHAEL FRANCIS,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 14, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed April 28, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/howley_michael_francis_14E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/howley_michael_francis_14E.html |

| Author of Article: | Barbara A. Crosbie |

| Title of Article: | HOWLEY, MICHAEL FRANCIS |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 14 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of revision: | 1998 |

| Access Date: | April 28, 2025 |