Source: Link

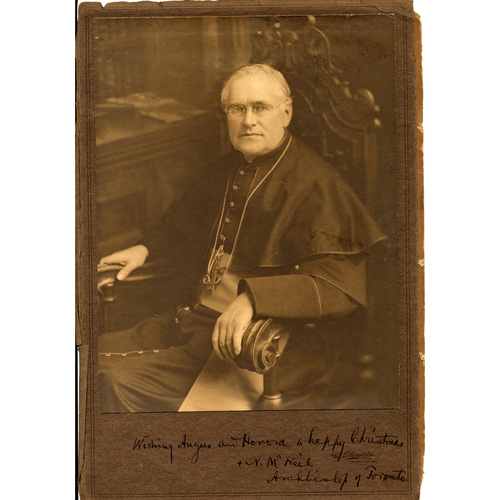

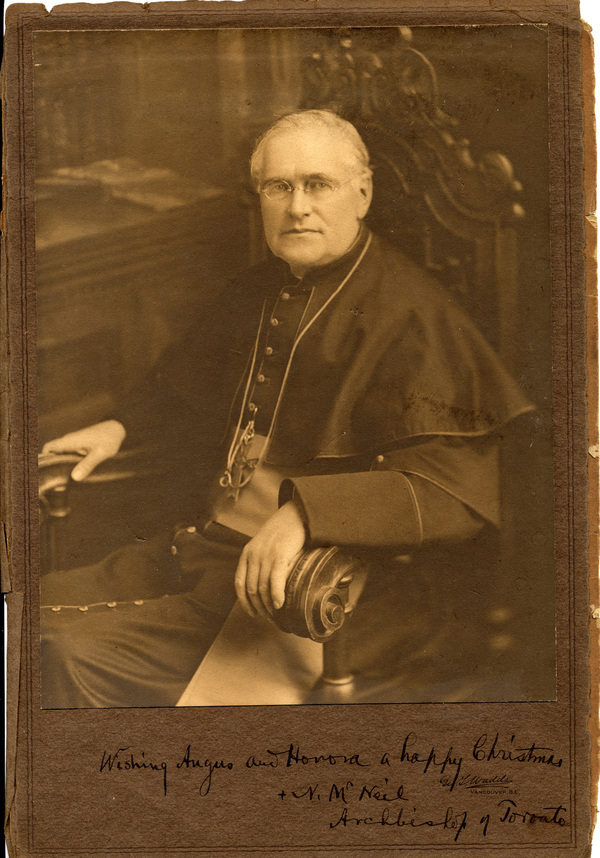

McNEIL, NEIL, educator, Roman Catholic priest, newspaper editor, and archbishop; b. 23 Nov. 1851 in Hillsborough (Hillsboro), N.S., eldest of the 11 children of Malcolm McNeil and Ellen Meagher; d. 25 May 1934 in Toronto.

Neil McNeil’s father was a descendant of immigrants from the island of Barra, Scotland, and his mother’s family had emigrated to Nova Scotia from Kilkenny (Republic of Ireland). Throughout his life, both in his personal correspondence and in public statements, McNeil would reveal a great love for his Scottish and Irish heritage. The family owned a forge and a small shop in Hillsborough in the parish of Mabou, Cape Breton Island. Neil attended the local school and trained as an apprentice blacksmith with his father. His younger brother Daniel worked in the store and was chosen by the parents to be the child who would receive a formal education. The schoolmaster, having discovered Neil’s prowess in mathematics, persuaded the family to let him pursue further learning as well, and in 1869 Neil entered St Francis Xavier College in Antigonish.

After graduating with high honours in 1873, McNeil taught secondary school in Antigonish County. In early 1874 John Cameron*, coadjutor to Colin Francis MacKinnon*, bishop of Arichat, sent McNeil to the college of the Sacred Congregation of Propaganda in Rome, where he earned doctorates in theology and philosophy after six years. On 12 April 1879 he was ordained priest in the basilica of St John Lateran in that city. He did not return immediately to Nova Scotia because Cameron ordered him to spend a year studying higher mathematics, astronomy, and French in Marseilles, starting that summer. McNeil would become known as a gifted linguist: fluent in English and French, he was also proficient in Gaelic, Italian, Latin, and Greek.

In the fall of 1880 McNeil began a brief career as a professor of science and Latin at St Francis Xavier, and the following year he founded a weekly newspaper, the Aurora. He acted as editor and contributed much of the copy until 1884. That year, owing to his experience as a member of the board of St Francis Xavier College and a term as vice rector, he was made rector, a position that he would hold for the next seven years. In addition to being chief administrative officer, he served as bursar, taught classes, purchased food from local farmers, supervised the culinary staff, worked as an infirmary nurse, and launched a second local newspaper, the Casket. His tenure at St Francis Xavier was notable for an ambitious building campaign undertaken in an effort to entice more students; the project included a new gymnasium and the expansion of the main structure to incorporate additional dormitories, offices, classrooms, a refectory, a library, and a chapel. In his capacity as editor of the Casket, he ran foul of Cameron, now bishop of the diocese (which had been renamed Antigonish in 1886), during the weeks leading up to the federal election of 1891. Cameron, an outspoken Conservative, claimed that McNeil’s editorial policy of political neutrality was tantamount to a “Grit conspiracy.” Not long afterwards Cameron sent McNeil to a less prominent pastoral setting at West Arichat on Cape Breton, and within a few months he was transferred to the Acadian parish of D’Escousse on Isle Madame. There McNeil worked among francophone Catholics for nearly three years, until he was appointed titular bishop of Nilopolis and vicar apostolic of Western Newfoundland (St George’s), a recently created vicariate that encompassed all of the territory from the south shore along the Gulf of St Lawrence and up the coast to the Strait of Belle Isle. On 20 Oct. 1895 he was consecrated bishop at St Ninian’s Cathedral, Antigonish, by his former bishop, Cameron, his future superior, Bishop Michael Francis Howley* of St John’s, and Bishop James Charles McDonald* of Charlottetown.

McNeil’s life in the remote vicariate called upon the breadth of his ecclesiastical, linguistic, and intellectual talents as well as the practical skills gleaned in his father’s workshop. The region was marked by disparate settlements of native-born Newfoundlanders, some of them Micmac (Mi’kmaq) and Acadian, and immigrants from Canada, Scotland, and Ireland; Irish Catholics constituted the majority. Living in coastal villages and inland communities, the people had limited contact; there were few trails in this rugged frontier, which meant that most travel was undertaken by sea along the French Shore. Using his experience as a blacksmith, stonemason, roofer, and carpenter, McNeil helped with the building of churches, rectories, and roads. He moved the site of the cathedral and the episcopal residence from isolated Sandy Point to St George’s, which was served by a railroad, and he was responsible for the construction of nearby St Michael’s College in 1899. When the vicariate was elevated to the diocese of St George’s in 1904, he became its first bishop.

He travelled great distances to help his people; in 1908, when there was fear of a food shortage on the west coast of Newfoundland, he ventured to St John’s to ensure that the railroad [see Sir William Duff Reid*] would make every effort to continue its trips to the region throughout the winter. With his common touch and his fearlessness about hard labour, McNeil endeared himself to his parishioners, many of whom would write to him regularly after he left. In every charge, McNeil drew from his roots, successfully requesting priests, sisters, and others from his native province to assist with education and advance the work of the church in outlying regions. In this way he would extend the influence of the diocese of Antigonish right across Canada in the early 20th century.

By 1910 the Vatican had acknowledged McNeil’s work in eastern Canada and decided to assign him to the western frontier – the fledgling archdiocese of Vancouver. The relocation was by no means a smooth one. The archdiocesan status had recently been transferred from Victoria to Vancouver, where historically the church had been managed by the French-speaking religious of the Oblates of Mary Immaculate. When the archiepiscopal see of Vancouver became vacant in 1909, there were two rival terna, or slates of candidates, for bishop: one submitted by the Oblates, who wished to retain control of the region, and a second suggested by the anglophone diocesan clergy, headed by Bishop Alexander MacDonald* of Victoria, who happened to be McNeil’s long-time friend from Mabou. In a controversial move that signalled a new era for church governance in British Columbia, the apostolic delegate to Canada, Monsignor Donato Sbarretti y Tazza, with the strong endorsement of the English Canadian hierarchy, recommended that the Vatican transfer McNeil to the contested archdiocese. Consequently, on 19 Jan. 1910 McNeil was formally designated archbishop of Vancouver.

Although his stay would be brief, it was noteworthy in that he continued his frantic pace of building infrastructure. Fearing the overwhelming presence of Protestants in the province, he endeavoured to create new Catholic settlements in the thinly populated diocese, and to that end he purchased 760 acres of land in the Fraser valley. When McNeil had arrived in Vancouver he knew no one there and had no church or residence, but he set a startling pace of growth: in two years he constructed 13 churches, two convent schools, and a hospital. His overextended building projects and some poor land investments would create great financial difficulties for the archdiocese [see Timothy Casey], especially when the real-estate market collapsed, but at the national level the church benefited significantly from his continued development of links between the long-standing dioceses of eastern Canada and those emerging on the other side of the country. With the assistance of friends and relatives, including his uncle and close confidant Nicholas Hogan Meagher, he sponsored alumni from St Francis Xavier to come to the Pacific coast as teachers, perhaps with a vision of some day forming a Catholic university in Vancouver that could become a veritable “St FX in the West,” as he described it in a letter to the college president, Father Hugh Peter MacPherson.

McNeil’s time there was cut short by his appointment on 10 April 1912 to the archdiocese of Toronto, arguably English Canada’s most prominent and influential Catholic see. In the opinion of his close friend Bishop MacDonald, the Vatican wanted McNeil to improve the position of the Catholic Church Extension Society, a home-mission organization from which McNeil himself had drawn financial support when erecting parishes in Vancouver, and to set Toronto’s new St Augustine’s Seminary on firm foundations. Situated on farmland at the top of the scenic Scarborough Bluffs overlooking Lake Ontario, St Augustine’s had been established by McNeil’s predecessor, Fergus Patrick McEvay*, and was nearing completion, thanks to the philanthropy of brewer Eugene O’Keefe*, when McEvay died in 1911. McNeil spent a considerable amount of time finishing projects in British Columbia and did not arrive for his installation in Toronto until December 1912. The seminary became an early priority. He made it clear in a February 1913 pastoral letter that, while scholarship was important, “holiness of life and consecration of purpose in the seminarians are more important.” His assertion that the seminary could be an agency of unification for Canada reflected his perception of the church as a truly national institution. McNeil intended that its students would be drawn from all regions of the country, and therefore St Augustine’s could potentially “do much to harmonize the many elements of Canada’s population. Our Church and our Country are both vitally interested in securing this harmony.” McNeil initiated the first annual archdiocesan collection for the seminary and recruited professors to teach a curriculum that included scriptural study, asceticism, theology, catechetical pedagogy, philosophy, ecclesiastical history, and such practical courses as bookkeeping and parish administration. He also arranged for the Sisters of St Martha of Antigonish to take care of domestic needs in the residence. Within five years McNeil’s prognostications about the seminary’s unique influence were materializing: there were students from 12 Canadian dioceses, as well as representatives from Newfoundland, the United States, and the Ukrainian Catholic Eparchy in Canada.

Work with the Catholic Church Extension Society (CCES) and its president, the Reverend Alfred Edward Burke*, did not go as smoothly. The aims of the society, which had been set up by McEvay in 1908 and had received a papal charter two years later, were to finance missionary activity among First Nations, assist in building churches and schools in the west, and accommodate the needs of immigrants, who had been arriving in record numbers since 1896. The CCES owned the weekly newspaper the Catholic Register and Church Extension, and Burke, an outspoken imperialist and Conservative with a controversial vision of the church’s role in Canada, served as its editor. The society’s influential circle included O’Keefe, Sir Charles Fitzpatrick*, chief justice of the Supreme Court of Canada, Sir Thomas George Shaughnessy*, president of the Canadian Pacific Railway, and a host of other notable Catholic businessmen. When McNeil became chancellor of the society in 1913, it had not reached its potential for fund-raising and had alienated most of its French Canadian benefactors by advancing the propagation of the faith by means of the English language. McNeil undertook a thorough study of the CCES and invited confidential comment on it; the letters he received from concerned bishops and laymen across Canada confirmed his worst fears that neither the leadership nor the overall missionary strategy was satisfactory. At his first meeting with the board of governors in April of that year, he proposed several changes, all of which aroused swift and vociferous opposition from Burke and his allies. The acrimony among the officers continued for two years, with McNeil powerless to remove Burke because the CCES presidency was a papal appointment. In 1915 Burke resigned his position in order to join the chaplaincy service [see John Macpherson Almond] of the Canadian Expeditionary Force. McNeil then arranged for Thomas O’Donnell, a Toronto priest, to be named president; Joseph A. Wall, a former journalist colleague of McNeil’s from Antigonish, was hired as editor of the Catholic Register. Although the ill-feeling between the society’s adherents and the French Canadian hierarchy did not disappear entirely, the paper’s readership grew substantially, and the CCES dramatically increased its fund-raising success and raised its standing in the home-mission field.

Throughout his tenure in Toronto, McNeil would focus his attention on Catholic immigration, both nationally and locally. He continued the policy of his predecessor by inaugurating a national parish for each immigrant group that appeared able to sustain one. His quick response to newcomers reflected a desire not only to provide familiar, comfortable surroundings in which they could worship, but also a determination to thwart any attempts by local Protestant congregations, especially the Methodists and Presbyterians, to poach recent arrivals. McNeil sought secular priests and members of religious orders from the parishioners’ countries of origin. To erect special parishes within the bounds of existing English-speaking ones, it was necessary to get permission from Rome, and McNeil often circumvented red tape to expedite the process. After his death his successor, James Charles McGuigan*, would ask the Vatican to officially approve all of these parishes retroactively. During his 22 years as archbishop, McNeil oversaw the creation of parishes for Italians, Poles, Hungarians, Maltese, Syrians, and Slovaks. Additionally, he assisted the Ukrainian Catholic Eparchy in establishing itself in Toronto, Welland, and Oshawa. In the early 1920s, with a view to helping Catholic immigrants throughout the country, he sanctioned the founding of the Sisters of Service by Redemptorist Father George Thomas Daly, Father Arthur T. Coughlan, and teacher Catherine Donnelly. This Toronto-based order served new arrivals in ports, downtown hostels, and schoolhouses near homesteads. In February 1933 McNeil would also give his blessing to Catherine Doherty [Kolyschkine*], a refugee belonging to the Russian nobility, who believed she was being called to sell all her possessions and set up Friendship House in Toronto’s inner city in an effort to provide aid to immigrants, especially Russians, and prevent communists from enlisting them.

In his pastoral work McNeil never strayed from his roots as a skilled labourer, and in Toronto he became a defender of the rights of workers. In a 1916 address to the convention of the Bricklayers, Masons, and Plasterers’ International Union of America, McNeil made clear his message to employers: “Pay your men current wages, give your men an equitable share in your profits, and give them also the care and friendship you owe them as fellow-men and Christians.” He publicly backed workmen’s compensation and would often discuss matters of social justice and Catholic action with those who accompanied him on his long Saturday walks through the city. He used the pages of the Catholic Register to inform readers about labour issues. In 1915 he hired Henry Somerville*, a British social activist and journalist, to come to Toronto and write a weekly “Life and labour” column. When Somerville had to resign his position for family reasons in 1919 (he would not resume his duties at the Register until 1933), McNeil filled in by contributing articles of interest to the working man and commentaries on the church’s social teaching. In public he admitted that he was not a great orator. Still, as was noted in the Catholic press, “he would speak to an audience impromptu, briefly, unpretentiously, but his remarks would be full of suggestion and stimulating to those who looked for substance and not show.” With the worsening of the Great Depression, McNeil was concise and poignant in his remarks at Toronto City Hall about the malaise facing its citizens and the world in 1932: “Competition, greed and avarice – these words have changed, it seems to me, to enterprise, business sense and laudable ambition.… I say to business people that we give them now an opportunity to exercise real responsibility.” He engaged in ways to facilitate the lives of working-class families, migrant workers, and the marginalized by developing the St Elizabeth Visiting Nurses’ Association, St Mary’s Infants’ Home, the Catholic Big Brothers, Rosalie Hall for working women, and the Columbus Boys’ Camp, and he amalgamated all Catholic aid organizations under the umbrella of the Federation of Catholic Charities.

McNeil, like his priest-professor confrères in Antigonish, believed that education was the best agent of social progress. Not surprisingly, he became a leader in the fight to improve Catholic schools nationwide and was an advocate for the engagement of Catholics in higher education. He oversaw the Toronto Separate School Board’s funding to De La Salle College and St Joseph’s College [see Mary Ann Whalen], as well as the expansion of existing elementary schools. Between 1919 and 1927 renovations were completed at 25 Catholic schools, and 16 new ones were built to accommodate increased demand. He also confronted the Ontario government on what were considered the two key education issues of the day: the refusal to fund directly Catholic secondary schools and the disinclination to amend the corporate and business tax allocations, which unless specifically directed to Catholic schools by Catholic-owned businesses went almost entirely to public schools [see Sir Richard William Scott*]. To address the first concern, he encouraged the archdiocesan board of Tiny Township in Simcoe County to challenge the denial of public funds to Catholic secondary schools. The case was launched in 1925, but it was struck down by both the local court and the Ontario Court of Appeal, with the justices divided along denominational lines. In 1928 the final appeal was heard by the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council, which stated that although the Ontario legislature could not abolish Catholic schools under section 93 of the British North America Act, it had discretionary authority over regulation and funding in education and was not constitutionally obligated to provide money to separate schools. In the wake of this loss McNeil enlisted businessman Martin James Quinn to form the Catholic Taxpayers’ Association as a means of pressuring the government to effect a more equitable distribution between public and separate schools.

McNeil’s interest in education included reform in religious pedagogy. He questioned rote learning in religion classes, particularly the use of the well-known Baltimore and Butler’s catechisms, which required students to memorize and repeat verbatim the answers to specified questions about the faith. Instead, after canvassing educators, he initiated the development of an innovative catechetical method that relied more on religion as life experience.

McNeil was also a proponent of higher education, believing that Catholics would not become leaders in English Canadian society without pursuing the programs offered by post-secondary institutions. He encouraged study at the University of Toronto across its many disciplines. As a way of convincing the community that its youth need not risk their faith, he established Newman Hall on campus and invited the Paulist Fathers of New York City to minister to Catholic students there. He was a strong supporter of St Michael’s College, which had been federated with the University of Toronto just two years prior to McNeil’s appointment to the bishopric; it became co-educational in 1911. The archbishop was active in ensuring that the work of the newly affiliated St Joseph’s College and Loretto College [see Margaret O’Neill*], both for women, was integrated into the schedules and curriculum of St Michael’s. The Catholic Register acknowledged that, under McNeil’s watchful eye, the academic standards had been enhanced and St Michael’s had become a “Mecca of … great scholars of international reputation,” among them the philosophers Étienne Gilson and Jacques Maritain, and the scientist and educationist Bertram Coghill Alan Windle. In 1929, inspired by an increased interest in medieval scholarship, McNeil and the priest-professors of the Congregation of St Basil, including Robert Francis Forster*, founded the Institute (later Pontifical Institute) of Mediaeval Studies at St Michael’s College, with Father Henry Carr* as its first president.

McNeil’s vision for the members of his archdiocese was that they would engage with members of their communities, including non-Catholics, as full citizens and contributors to Canadian society. His own leadership set an example for those whom he served. He cultivated excellent relations with local Protestant groups, helping to dispel Toronto’s stereotypical image as the so-called Belfast of Canada. In measured tones and with great diplomacy he also sought justice for Catholics and Jews, who often faced discrimination from employers in private industry and the public service. Maurice Nathan Eisendrath, chief rabbi at Holy Blossom Temple, spoke of McNeil as having “a great soul indeed, a kindly and sympathetic spirit, and yet withal possessed of a fine prophetic ardor for the cause of righteousness and justice.” McNeil was twice awarded an honorary lld: in 1920 by Dalhousie University; and in 1925 by the University of Toronto (the first Catholic bishop so acknowledged by the institution), in recognition of his work in the church in the city and what was described as his “goodness” within the community.

McNeil’s engagement with the non-Catholics of the city and province was put to the test during World War I. Soon after Great Britain’s declaration of war against Germany, which automatically made Canada a belligerent, McNeil affirmed the imperial war effort, encouraging Catholics to donate to the Canadian Patriotic Fund and to join the Canadian Expeditionary Force. In August 1914 he implored his flock to pray for peace, but he also said: “You do not need to be reminded of the duty of patriotism. You are as ready as any to defend your country and to share the burdens of the Empire.” Shortly after making this statement, he spoke at a recruitment meeting for Toronto and York County, during which he linked achieving victory on the battlefields to cultivating unity and peace among the city’s Christians: “in that conflict there is no difference between Protestants and Catholics.” He also took aim at Henri Bourassa* and his criticism of the Quebec bishops’ endorsement of the war effort [see Paul Bruchési], chiding the editor of Le Devoir for threatening the unity of both the church and the nation. McNeil quickly became one of Canada’s leading clergymen in fostering public participation. He allowed troops to be billeted on church property, upheld enlistment in specific battalions, permitted at least seven priests to be released from their pastoral duties to serve in the Canadian Chaplain Service, donated personally to Victory Loan campaigns and encouraged his priests to do the same, and placed advertising for the cause in every parish church. Likewise, he promoted the national registration of all able-bodied men during 1916 and 1917, and commended the imposition of conscription by Sir Robert Laird Borden’s government. In an effort to assist all soldiers – Catholic and non-Catholic – both in training camps and at the front, McNeil used his influence to further the nationwide drive to fund the overseas establishment of multi-purpose recreation centres called Catholic Army Huts. In 1917 and 1918, led by the program’s national director, Major Reverend John Joseph O’Gorman, and with the sponsorship of the Knights of Columbus, the campaign urged Catholics and Protestants across Canada to contribute towards the construction of these huts; over $1 million was raised. McNeil’s promotion of a similar ecumenical effort in Toronto netted over $200,000.

Despite such public displays of patriotism by McNeil, his clergy, and most of his flock, whose enlistment rates were high, there were Protestant detractors who claimed, citing the case of Quebec, that Catholics were not contributing to the cause and that the pope was a German sympathizer. McNeil responded to this rhetoric in his own manner: in 1918 he wrote a short treatise, The pope and the war, which argued that Benedict XV sided with neither the Germans nor the Allies but instead had been neutral and an agent of peaceful reconciliation. The pamphlet was read from the pulpits of all Toronto Catholic churches, and its first print run of 5,000 was distributed across Canada amid much praise from both Catholics and non-Catholics, including such secular newspapers as the Globe.

During the war relations between English- and French-speaking Roman Catholics in Canada became strained, particularly over recruitment, conscription, and the ever-heated question of Regulation 17, which prohibited French as a language of instruction in Ontario beyond the first two years of schooling [see Philippe Landry*; Joseph Octave Reaume; Sir James Pliny Whitney*]. McNeil had been fortunate to arrive in Toronto after anglophone bishops and Franco-Ontarians had clashed over the provisions of Regulation 17. Regarded as a newcomer and, despite his maternal lineage, not a “maudit Irlandais” (“blasted Irishman”) like Bishop Michael Francis Fallon of London, McNeil attempted to broker peace by addressing French Canadian leaders in private meetings, through the Knights of Columbus nationwide, and in essays printed in books and major newspapers, such as Montreal’s La Presse, in which he published a series of articles in 1918. When he informed Émile Roy, chancellor of the archdiocese of Montreal, about the papers, he explained, “Racial differences and antagonisms can become a very real danger to the Catholic Church in Canada, [and] I am simply trying to lessen that danger.” These commentaries on building national unity, which were acclaimed by La Presse managing editor Oswald Mayrand and excerpted in English by the Montreal Daily Star [see Hugh Graham], became McNeil’s harbinger of Bonne Entente, a movement founded by John Milton Godfrey* and Arthur Hawkes that he and leaders from Quebec and Ontario hoped would repair the damage done to national unity during the war. One correspondent, who identified himself as “A Pea Soup” Montrealer, praised McNeil’s initiatives, stating that the “Shamrock & Fleur de lis should grow in the same pot.”

Wherever he served, McNeil left a legacy as a builder. When he arrived in Toronto, there were 20 Catholic parishes; during his 22 years there he oversaw the initiation of 26 more as the city’s Catholic population rose from 43,080 to more than 90,000. Throughout the entire diocese, which at the time included what would become the diocese of St Catharines, McNeil authorized 15 new parishes. In addition he managed to bring in several religious orders – among them the Grey Sisters of the Immaculate Conception, the sisters of the Congregation of Notre-Dame, the Congregation of St Paul, the Vincentian Fathers, the Ursulines, and the Franciscans – and he welcomed back the Jesuits, whose priests had worked there in the 19th century, and the Sisters of Holy Cross. He was also influential in upholding the Catholic Women’s League, founded in 1919 [see Bellelle Guerin*; Katherine Angelina Hughes*], which he regarded as a means by which women could promote the faith and foster greater Canadian patriotism and national unity.

When Archbishop Neil McNeil died on 25 May 1934 after a short illness, his loss was mourned by his family, thousands of Catholics, and many non-Catholics. Noted Protestant leaders from all denominations in Toronto praised him for his service to his church and to the entire community. The secular media were unusually effusive in their tributes to McNeil as a peacemaker, scholar, skilled tradesman, and great Canadian. “If need be,” stated the Toronto Daily Star, “he could shoe a horse, repair an engine, build a road, draw plans for a building, do carpentering and act as an architect and contractor.” Perhaps one of the most fitting epitaphs came from the usually Orange-leaning Evening Telegram, which eulogized, “In the life of the community he was respected and admired as a patriot, who was always ready and anxious to cooperate in any movement for the public good.”

Neil McNeil is the author of several treatises and essays, including The pope and the war (Toronto, 1918), Christian unity (Toronto, [1921]), The mass ([Toronto], 1925), The school question of Ontario ([Toronto], 1931), and Schools of long ago (Toronto, 1932), as well as the article “Canadian national unity,” in The new era in Canada; essays dealing with the upbuilding of the Canadian commonwealth, ed. J. O. Miller (Toronto, 1917), 193–207.

Antigonish Diocesan Arch. (N.S.), 8 (A. A. Johnston papers), ser.1, subser.1, folder 2, McNeil to John R. MacDonald, 6 July 1918 and 26 May 1919. Arch. of the Archdiocese of Montreal, 255.104/918-001, McNeil to Chancellor Roy, 22 April 1918; 255.104/918-003, McNeil to Bruchési, 10 April 1917. Arch. of the Archdiocese of Ottawa, Gauthier papers, Donatus Sbarretti to Gauthier, 14 Aug. 1909, and Gauthier to Sbaretti, 8 Nov. 1909. Arch. of the Archdiocese of St John’s, 106/33 (Michael Francis Howley papers), 11, denominational statistics, Bay St George, 1891–1901, and McNeil to Howley, 15 July 1909. Arch. of the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Toronto, MN (McNeil papers). LAC, Census returns for the 1911 Canadian census; MG27-IIC1, vol.15, McNeil to Fitzpatrick, 8 Nov. 1913, p. 6540; R5240-3-7 (Sir John Thompson fonds, Political papers, Letters received), Cameron to Thompson, 16, 27, 30 Dec. 1890. St Francis Xavier Univ. Arch. (Antigonish), RG 5/7 (D. A. Chisholm presidential fonds), 1337, McNeil to Chisholm, 30 Sept. 1897; RG 5/8 (Alexander M. Thompson presidential fonds), 1169, McNeil to Thompson, 25 April 1902, and 1170, McNeil to Thompson, 23 Aug. 1902; RG 5/9 (H. P. MacPherson presidential fonds), 8378–79, McNeil to MacPherson, 3 Jan. 1911. Catholic Register (Toronto), 13 Feb., 11 Sept. 1913; 26 Feb., 20, 27 Aug. 1914; 20 Jan., 6 April 1916; 7 March, 2 May 1918; 17 July, 4 Dec. 1919; 24, 31 May 1934. La Presse, 19 avril 1918. Archdiocese of Toronto, Walking the less travelled road: a history of the religious communities within the Archdiocese of Toronto 1841–1991 (Toronto, 1993). J. R. Beck, “Contrasting approaches to Catholic social action during the Depression: Henry Somerville the educator and Catherine de Hueck the activist,” in Catholics at the “gathering place”: historical essays on the Archdiocese of Toronto, 1841–1991, ed. M. G. McGowan and B. P. Clarke (Toronto, 1993), 221–31; To do and to endure: the life of Catherine Donnelly, Sister of Service (Toronto, 1997). George Boyle, Pioneer in purple: the life and work of Archbishop Neil McNeil (Montreal, 1951). The British Columbia orphan’s friend: historical number, ed. Alexander MacDonald (Victoria, 1914). J. D. Cameron, For the people: a history of St Francis Xavier University (Montreal and Kingston, Ont., 1996). Canadian men and women of the time (Morgan; 1898 and 1912). Canadian R.C. bishops, 1658–1979, comp. André Chapeau et al. (Ottawa, 1980), 93. The cathedral of the Most Holy Redeemer and of the Immaculate Conception: souvenir of the official opening, Corner Brook, Nfld – Sept. 9, 1956 (n.p., 1956). Church and society: documents on the religious and social history of the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Toronto from the archives of the archdiocese, ed. J. S. Moir, with foreword by A. M. Ambrozic (Toronto, 1991). Cyclopædia of Canadian biog. (Rose and Charlesworth), vol.3. R. T. Dixon, We remember, we believe: a history of Toronto’s Catholic separate school boards, 1841 to 1997 (Toronto, 2007), 126, 135, 142, 153–56, 181–86. J. C. Hopkins, Canada at war, a record of heroism and achievement, 1914–1918 (Toronto, 1919), 331. M. G. McGowan, The imperial Irish: Canada’s Irish Catholics fight the Great War, 1914–1918 (Montreal and Kingston, 2017); “The Maritimes region and the building of a Canadian church: the case of the diocese of Antigonish after confederation,” CCHA, Hist. Studies, 70 (2004): 48–70; The waning of the green: Catholics, the Irish, and identity in Toronto, 1887–1922 (Montreal and Kingston, 1999); “A watchful eye: the Catholic Church Extension Society and Ukrainian Catholic immigrants, 1908–1930,” in Canadian Protestant and Catholic missions, 1820s–1960s; historical essays in honour of John Webster Grant, ed. J. S. Moir and C. T. McIntire (New York, 1988), 221–43. Peter Meehan, “The East Hastings by-election of 1936 and the Ontario separate school tax question,” CCHA, Hist. Studies, 68 (2002): 105–32. Lina O’Neill, “Catholic Women’s League of Canada,” St. Joseph Lilies (Toronto), 8 (June 1919–March 1920), 4: 73–77. Ontario Catholic directory, Toronto, 1980: 18–46, 47–50, 77–80. Ontario Catholic yearbook (Toronto), 1920: 25. The people cry – “Send us priests”: the first seventy-five years of St. Augustine’s Seminary of Toronto, 1913–1988, ed. K. M. Booth (Toronto, 1988). Thomas Sears, “Report of the missions of the prefecture of St George’s, west Newfoundland” (Quebec, 1877; available at the Arch. of the Archdiocese of St John’s, 106/33/3). Joseph Sinasac, Fateful passages: the life of Henry Somerville, Catholic journalist (Ottawa, 2003). Standard dict. of Canadian biog. (Roberts and Tunnell), vol.2. F. A. Walker, Catholic education and politics in Ontario … (3v., 1955–87, 1–2 repr. 1976), 2: 323–38, 355–433.

Cite This Article

Mark G. McGowan, “McNEIL, NEIL,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 16, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed December 31, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/mcneil_neil_16E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/mcneil_neil_16E.html |

| Author of Article: | Mark G. McGowan |

| Title of Article: | McNEIL, NEIL |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 16 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 2020 |

| Year of revision: | 2020 |

| Access Date: | December 31, 2025 |