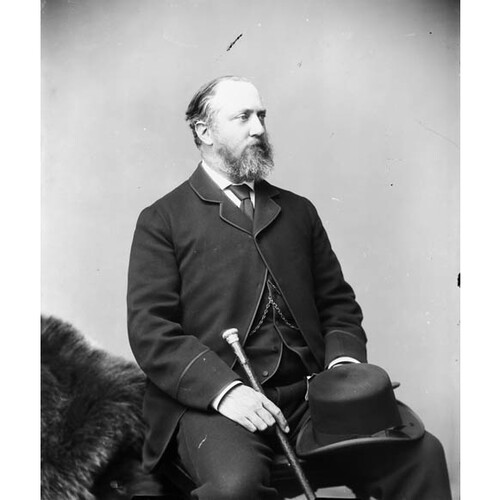

Source: Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

STANLEY, FREDERICK ARTHUR, 1st Baron STANLEY and 16th Earl of DERBY, governor general; b. 15 Jan. 1841 in London, England, second son of Edward George Geoffrey Stanley, 14th Earl of Derby, and Emma Caroline Wilbraham; m. there 31 May 1864 Lady Constance Villiers, and they had eight sons and two daughters; d. 14 June 1908 at Holwood, near Hayes, Kent, England.

Educated at Eton College, Frederick Arthur Stanley joined the Grenadier Guards in 1858 and retired in 1865 as a captain. He was elected to the House of Commons that year for Preston, near the family estates in Lancashire, in the Conservative interest. After his famous father resigned as prime minister in February 1868, and Benjamin Disraeli succeeded as leader of the party, Stanley got his first official appointment, as civil lord of the Admiralty. In November he successfully contested the long-time Liberal seat of North Lancashire, which he represented until 1885, when redistribution compelled him to change to Blackpool. He was raised to the peerage in his own right as Baron Stanley of Preston in 1886.

Unlike his father, Stanley was no orator and was not comfortable in the House of Commons. He had, however, considerable administrative ability and a good head for business, talents that Disraeli utilized when he appointed him financial secretary to the War Office. In April 1878 Stanley was made secretary of state for war, in which office he continued the work of army reform begun by Edward Cardwell. His appointment was popular with the army and its commander-in-chief, the Duke of Cambridge. At the defeat of the Conservatives in 1880, he resigned office. In 1885–86 he served as colonial secretary under Lord Salisbury.

On 1 Feb. 1888 Salisbury offered him the governor generalship of Canada. Stanley accepted almost at once. He was gazetted on 1 May and was in Quebec a month later. He and his wife were delighted with the prospects from their official residences in Ottawa and Quebec. Lady Stanley wrote to her sister, “We are up to now very much pleased with our new homes & all the people both at Ottawa & Quebec are most cordial & charming to us. F. [Frederick] has made a very great & good impression by his french.” Within a year or two the Stanleys had developed interests in both east and west. Stanley House, as it came to be called, was a “cottage,” a country house really, near New Richmond, Que., facing Baie des Chaleurs. Stanley bought it in the summer of 1888. Honoré Mercier*, premier of Quebec, stayed there that August and thanked the governor general for the use of it. In September and October 1889 the Stanleys went west on the Canadian Pacific Railway and were enthusiastic. “We are filled with wonder & admiration for the minds that conceived the idea of this wonderful railroad & of the energy & courage of those who carried it out,” Lady Stanley wrote 16 miles from Regina. During that trip Lord Stanley officially opened Stanley Park in Vancouver, named after him the year before and located on land given by the Canadian government to the city from a military reserve.

Governor General Lord Stanley had his problems with Canadian militia and defence. He knew a good deal about the army, and sought to impress on Prime Minister Sir John A. Macdonald* the importance of a small but efficient militia, smaller even than what the dominion then had. You know, he informed Macdonald in 1890, “it is openly said that the disposal of the money voted for the Militia is not always that for which it is voted, nor is it influenced only by considerations of the well being of the force.” Macdonald was quick to appreciate Stanley’s expertise; “You cannot speak too plainly to me,” he wrote back. The state of the militia, Macdonald said, was partly the fault of its minister, Sir Adolphe-Philippe Caron, but was also owing to staff who were Grits and quite unfit on other grounds. Caron kept them on lest he be charged with political enmity.

Stanley was fastidious, circumspect, not to say timid, in dealing with the vagaries – the tracasseries – of Canadian politics. In January 1891, when Macdonald wanted to dissolve parliament over Edward Farrer*’s annexationist pamphlet, Stanley wrote him that he found little treasonable language in it. Then, like Pontius Pilate, he washed his hands. “Of course, however, you know best. I don’t venture to express an opinion one way or the other, as to the policy of using this unpublished paper as a weapon of political war.”

As Macdonald lay dying at the end of May 1891, indecision by the governor general exacerbated the political crisis. Stanley was sure that the prime minister had named his own successor, in his will or somewhere, and he refused to appoint a successor until after Macdonald’s funeral. Justice minister Sir John Sparrow David Thompson* was impatient, not for himself, but with the indecision that racked Ottawa before and after Macdonald’s death on 6 June. No nominal paper was found. Stanley preferred Thompson, but Thompson knew that Protestant Ontario would have a difficult time accepting a Roman Catholic prime minister. Stanley was not even sure the government would survive; he had surmised on 4 June that it might well go to pieces.

Once the dust had settled and John Joseph Caldwell Abbott* had reluctantly agreed to serve as prime minister (from the Senate), it was clear that he and Thompson (leading in the House of Commons) were going to take hold of the Conservative party. They had Stanley’s blessing. There were difficulties, partly owing to Abbott’s reluctance to interfere with his cabinet colleagues, who kept pulling hard in different directions. As well, Canada was in the midst of a diplomatic wrangle with the Americans over the arrest of Canadian sealers in the Bering Sea. Two questions, the principle of access to the sea and the issue of damages, arose. The Canadians insisted the two had to be taken together, the British wanted them separated. Each had measured American intentions differently. Canada was, said Stanley, at the awkward stage when it could not stand alone, yet resented being led. In February 1892 he explained to Colonial Secretary Lord Knutsford that in his dispatches he had to ask questions and make applications, on behalf of his Canadian ministers, that looked idiotic; he did not like to refuse his ministers even though the British government, he strongly suspected, might find it impossible to grant their requests.

The imperial government also wanted Newfoundland joined with Canada, if that were possible without violating the feelings of Newfoundlanders and provided Canada would grant reasonable terms. In a letter to Colonial Secretary Lord Ripon in November 1892, Stanley noted that there was a meeting in Halifax on the subject. He thought that Premier Sir William Vallance Whiteway of Newfoundland might want to make a display of negotiating in order to generate political capital from a Canadian refusal. But if Whiteway were serious, Stanley said, Sir John Thompson would deal with him judiciously.

By this time Abbott was ill and had to give up the prime ministership. Thompson was now the only choice. On 23 November he met with Stanley and agreed to replace Abbott the following month. There was no longer the question of having to keep ministers in line: Thompson ran a tight ship, although he was away in Paris from March to June 1893 for the Bering Sea arbitration.

That was the point at which Stanley was forced to resign office, though his term was not to expire until September. His elder brother died childless on 21 April, and Stanley became the 16th Earl of Derby. There were pressing family reasons to return home. Leaving Canada in early July, he was now out of politics for good. He was grateful to Thompson for his great help “during the stormy times which during the past five years, we have successfully weathered together.” And he was praised by Ripon for his conduct of Canada during a difficult time.

Stanley’s lasting gift to the nation was the large silver cup he donated in March 1892 for the best team in Canadian amateur ice hockey. A number of his sons, notably Arthur, delighted in the game, and with the Nova Scotian law clerk of the Senate, James George Aylwin Creighton*, as moving spirit, a junior team was formed in 1889 with the improbable name of the Rideau Hall Rebels. In 1890 Arthur was a founder of the Ontario Hockey Association. Doubtless his sons’ interest helped prompt the sports-minded governor general – he had provided a trophy and medal for curling – to present a cup for hockey. The Dominion Challenge Trophy was first awarded in 1893 to the Montreal Amateur Athletic Association, which won the first contest for the trophy, against Ottawa, the following year. Eventually known as the Stanley Cup, it was won in 1909 by a professional team, the Ottawa Senators, and is the oldest trophy competed for by professional athletes in North America.

Following his return to Britain, Derby served in 1895–96 as first lord mayor of Liverpool; there is a statue of him there in St George’s Hall. He was subsequently lord lieutenant of Lancashire. As befitted such a role, he returned happily to his old love of horse-racing. King Edward VII was a regular visitor at Knowsley Park, Derby’s huge estate eight miles from Liverpool. Derby was elected president of the British Empire League in 1904. He died four years later at Holwood, his house in Kent, and was buried at Knowsley Park.

Stanley was one of those quiet, careful proconsuls who are a credit to their class. Former prime minister Arthur James Balfour wrote to Lady Derby that her late husband had been one of his oldest and kindest friends, “a man who had a genius for inspiring affection among those who knew him.” With wide interests, kind, retiring, and transparently honest and sincere, he was not altogether fitted for the cut and thrust of political life. Since he lacked flamboyance, the impression he left is misleading. There was a great deal of knowledge and experience in Stanley, but it was deployed modestly and tentatively. Canadians remember him more for Stanley House, Stanley Park, and the Stanley Cup. He would not have minded that recollection, imperfect though it is.

The main collection of Lord Stanley’s papers is the Hobbs (Derby–Gathorne-Hardy) papers, in the library of Corpus Christi College, Univ. of Cambridge, Eng. An inventory of the collection is available at the Hist. mss Commission and National Reg. of Arch. (London), no.11916. The NA has microfilmed from it nearly all of the important letters relating to Stanley’s sojourn in Canada as governor general (MG 27, I, B7). The Stanley collection at the Liverpool Record Office (16th Earl of Derby corr.) deals primarily with his years in England, but includes two boxes concerning Canada. These contain mainly printed materials, including annual reports and government documents. There is also material concerning Stanley in the Thompson papers (NA, MG 26, D).

Gazette (Montreal), 1892–94. Ottawa Free Press, 1893–94. Times (London), 1 June 1864: 12. World (Toronto), 28 Nov. 1890. Burke’s genealogical and heraldic history of the peerage, baronetage and knightage, ed. Peter Townend (105th ed., London, 1970). CPG, 1891. Debrett’s peerage, baronetage, knightage, and companionage . . . (London, 1907). Dan Diamond and Joseph Romain, The Hockey Hall of Fame; the official history of the game and its greatest stars (Toronto, 1988). DNB. H. H. Roxborough, The Stanley Cup story (Toronto, [1964]). Types of Canadian women (Morgan): 85. Waite, Man from Halifax. S. F. Wise and Douglas Fisher, Canada’s sporting heroes (Don Mills [Toronto], 1974).

Cite This Article

P. B. Waite, “STANLEY, FREDERICK ARTHUR, 1st Baron STANLEY and 16th Earl of DERBY,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 13, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed December 31, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/stanley_frederick_arthur_13E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/stanley_frederick_arthur_13E.html |

| Author of Article: | P. B. Waite |

| Title of Article: | STANLEY, FREDERICK ARTHUR, 1st Baron STANLEY and 16th Earl of DERBY |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 13 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1994 |

| Year of revision: | 1994 |

| Access Date: | December 31, 2025 |